Much has been written of the enormous strides made by genuinely independent cinema in recent years. In 2004, nearly every review of Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation cited its “budget” of $218 and touted its desktop iMovie roots as a harbinger of things to come. Theatrical distribution for no-budget personal documentaries didn’t last long. YouTube would launch within six months.

Much has been written of the enormous strides made by genuinely independent cinema in recent years. In 2004, nearly every review of Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation cited its “budget” of $218 and touted its desktop iMovie roots as a harbinger of things to come. Theatrical distribution for no-budget personal documentaries didn’t last long. YouTube would launch within six months.

Nevertheless, digital moviemaking has been embraced as a uniquely democratic avenue, the kind of game-changer that fundamentally alters who makes and consumes media. The ease of digital production and dissemination cannot be denied, but neither should we assume that the film era presented insurmountable barriers to entry. If anything, the disappearance of analog workflows makes the achievements of the past all the more impressive. How did aspiring filmmakers ever master exposure, A/B roll cutting, synchronization, and magnetic sound recording? These technical hurdles were real, but they hardly stopped a flood of alternative media, dissident art, regional filmmaking, and genuine oddities from reaching the screen.

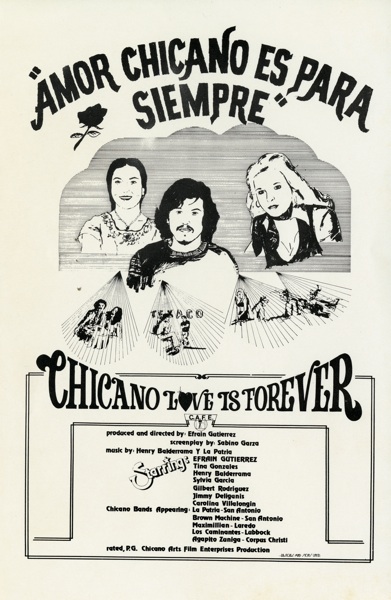

Efraín Gutiérrez is one of the least likely, most bewildering figures of the celluloid era. With minimal capital and technical experience, Gutiérrez managed to produce and distribute three features and one short film in the latter half of the 1970s—the first films to depict the Chicano community from the inside. The details of Gutiérrez’s career became the stuff of legend, particularly after the filmmaker’s 1980 disappearance. Some speculated that he’d been a drug runner or a hit man and financed his films through illicit means. The sympathetic critic Gregg Barrios made a case for Gutiérrez as a pioneering Chicano filmmaker while acknowledging the consensus view that his films were “sexist and racist diatribes that should be ignored and forgotten.”