Very few people have seen Michael Curtiz’s A Million Bid (1927), but it’s an interesting picture, moreso than its meager reputation would suggest. The film merits barely more than a paragraph in James Robertson’s The Casablanca Man: The Cinema of Michael Curtiz and earns a passing mention in Alan K. Rode’s newly released Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film. (Rode provides additional context on A Million Bid in his recent interview with Ben Sachs.) Yet the story of its production, release, and restoration of A Million Bid suggests a film of enduring, imponderable mysteries. Rather than attempt a critical evaluation of the film, I hope to demonstrate how rich and contradictory a record A Million Bid left behind in primary sources alone.

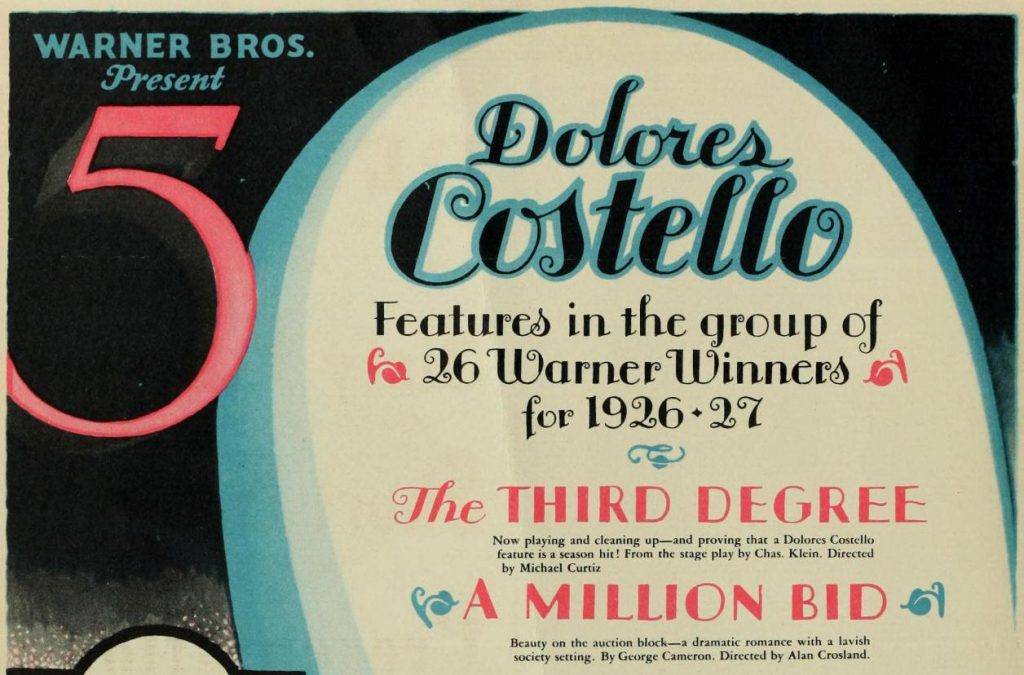

The neglect of A Million Bid is understandable. The script is rote melodrama, and the film itself (presumed lost for decades until a copy was rediscovered in Italy) is somewhat extraneous in assessing Curtiz’s legacy. It was Curtiz’s second American film, but his first, The Third Degree (1926), long ago preserved by the Library of Congress, seemed a sufficient example of his work from this period. The Third Degree was released amidst of flurry of Warner Bros. publicity, touting the studio’s newest filmmaker (already a veteran director of sixty films in Europe) as a technical wizard. “I do not see a scene with my eyes,” boasted Curtiz in a Los Angeles Times profile, “I see a scene with camera-eyes.” The film earned decent reviews, with favorable comparisons to E.A. Dupont’s Variete, one of the German imports frequently invoked as a rejoinder to pedestrian Hollywood technique.