Biography

The Films:

• The Scratchman (1980)

• Scratchman #2 (1982)

• You (1983)

• All Fucked Up (1983)

• Holiday Magic (1985)

• Meet … Bradley Harrison Picklesimer (1988)

• Fetal Pig Anatomy (1989)

• The Lester Film (1995)

• Comes to a Point Like an Ice-Cream Cone (1997)

About the Restorations

BIOGRAPHY

Heather McAdams (b. 1954) never set out to pursue a tidy career. When touring with her films in the 1980s and ’90s, McAdams often described herself as “a part-time cartoonist, performance artist, film instructor, junk salesperson, sculptor, painter, movie star, and ardent supporter of the Woolworth’s lunch counter.” This nomadic scavenger sensibility guides her filmmaking. Working primarily with found footage from her own extensive collection of 16mm prints, McAdams has produced a funny and ferocious body of work, much of it assembled from the detritus of American popular culture and refracted through an antic feminist lens. Her films exist at the accessible intersection of avant-garde cinema, underground comix, and gonzo documentary filmmaking.

McAdams grew up surrounded by film, and discovered an off-beat cinematic grammar hidden in plain sight: her own family’s home movies and the private cinematheque program constructed around them. “My father shot home movies,” recalled McAdams. “He shot 16mm and he had a good projector and he would show us films like commercials and previews for films, and it was just really incredible to have a sound movie theatre in your living room. I thought all the other kids in the world were doing that too! And he would stop the projector and make Uncle Stan pull the potato salad out of his mouth and then put it back in. And he’d go back and forth, stuff like that!”

Although McAdams studied painting as an undergraduate, she quickly turned to film. She studied filmmaking at the Art Institute of Chicago, but already had a sense of the basics from working at a film lab in Washington, D.C., which also supplied its fair share of absurd raw material for McAdams’s future work, including her early short The Scratchman. Much of her work reflects a grunt-level intuition for the possibilities of an unexpected splice, a connoisseur’s appreciation of cartoon music, countdown leader, and snippets of educational films that reveal far more than the official lesson at hand. “I enjoy making collisions of sounds and images,” says McAdams. “I like light shining through celluloid. I like the romance of it. I like cutting and pasting instead of pressing an electronic button …. It’s something that I have an unlimited attention span for.”

While McAdams never focused exclusively on filmmaking, she managed to keep projects alive while earning a living from visiting teaching stints in Lexington, St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Kingston, Rhode Island. While McAdams’s Chicago Reader cartoons were syndicated to alternative press outlets around the country, her growing body of film work circulated through Canyon Cinema and the Film-Makers’ Coop. She earned solo shows at Filmforum in Los Angeles and the Collective for Living Cinema in New York, and screened her new work at important showcases such as the Ann Arbor Film Festival and Chicago Filmmakers. The closest McAdams came to mainstream recognition was when MTV commissioned a 12-minute pilot called Cartoon Girl as the network’s putative estrogen-friendly follow-up to Beavis and Butthead; ultimately, the network decided to order a season of Daria instead.

McAdams’s films have special resonance for her adopted hometown of Chicago, where they have screened far beyond the usual boundaries of experimental work, in large part through her own off-beat curatorial initiatives and her distinctive cowgirl cartoonist public persona.

From 1997 to 2001, McAdams and her husband Chris Ligon owned and operated Chris and Heather’s Record Roundup and Collectibles, a resale shop at 2034 W. Montrose Ave. (“I collect stuff like you wouldn’t believe,” said McAdams. “I pick things up off the street. I collect textbooks where kids have drawn in them, scrapbooks that are thrown out.” “We opened the store to alleviate the guilt we had from buying all this stuff and never having company over,” added Ligon.) The shop hosted monthly programs of films and musical performances under the banner of “Chris and Heather’s Li’l 16mm Record Roundup Film Jamboree,” which often included McAdams’s own films as well as educational films, trailers, soundies, and other reels from her collection.

Even after the Record Roundup closed, McAdams and Ligon continued the Jamboree program under the guise of “Chris and Heather’s Country Calendar Show,” an annual music and film revue timed to the release of the latest edition of McAdams’s cartoon calendar celebrating the country western and rockabilly stars of yore. The Country Calendar Show began at The Hideout, but the jamboree quickly outgrew the space and moved to FitzGerald’s in suburban Berwyn, Illinois. McAdams has also hosted film screenings at Chicago Public Library’s Sulzer Regional Library (“Comic Strips, Movie Clips, and Potato Chips”), Schubas Tavern, and the Rainbo Club, substantially expanding her audience beyond those who patronize the city’s more conventional screening spaces.

THE FILMS

The Scratchman (1980) – 3 min, 16mm, color, sound

Constructed from ransacked and mutilated found footage, The Scratchman was one of McAdams’s earliest calling cards and “a reflection of my sophomoric silliness” according to the artist.

“I was working in a movie lab in Washington, D.C., that did a lot of government footage,” recalled McAdams, “and lots of times films would be out of sync or the color wouldn’t suit the client, so they would send them to the incinerator. And I’d pipe up, ‘I’ll take them to the incinerator!’ and I knew they were just garbage, so I would kind of pocket them.”

One such film provided the underlying material for The Scratchman. “I took a safety pin and duct-taped it to a chopstick, and I would put the film on a light table and scratch into it,” said McAdams. The result was a ribald satire of staid 16mm industrial filmmaking, with talking head footage of a generic middle-aged businessman (cheekily misidentified as Clifford J. Alexander, Secretary of the Army under President Carter) inundated with all manner of graffiti doodles and random thought bubbles. The soundtrack is zippy cartoon music and zany barnyard sound effects.

Preserved by Chicago Film Society with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. Laboratory services by Colorlab.

Scratchman #2 (1982) – 3 min, 16mm, color, sound

A sequel to The Scratchman. “Scratched lines and shapes bloat around this footage of an unknown businessman, sometimes forming hats, clown noses, arrows, etc.,” said McAdams. “He becomes a kind of pawn in my cruel little game. Sound is a music box which helps lift this once painfully boring footage to the level of high art.” The film was also an important turning point in McAdams’s career and the dissemination of her work: Scratchman II was the basis of a successful grant application to the Kentucky Arts Council Fellowship, which provided funding that allowed McAdams to make exhibition copies of her early films.

Preserved by Chicago Film Society with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. Laboratory services by Colorlab.

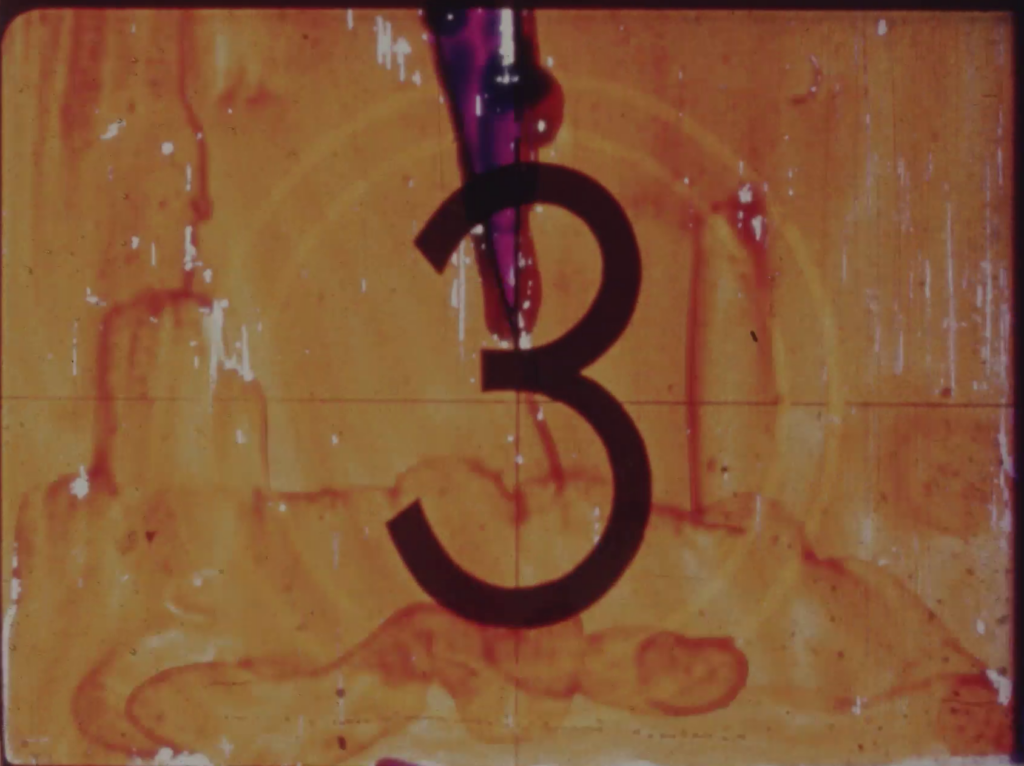

You (1983) – 4 min, 16mm, color, sound

Set to the propulsive rhythm of Brian Eno’s “King’s Lead Hat,” You is an exhilarating montage of countdown leader, hand-colored cats, leader ladies, and various scraps of “junk film” that are revealed to be anything but disposable. McAdams recalled deep dissatisfaction with another film she was making, to the point of preferring a roll of scrap leader, which then began shaping into You. An ecstatic engagement with a lifetime of celluloid, You plays like a teenage projectionist’s dream.

Preserved by Chicago Film Society with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. Laboratory services by Colorlab.

All Fucked Up (1983) – 8 min, 16mm, b/w, sound

A caustic send-up of adolescent anxiety, as seen through a barrage of clips from sex ed and social hygiene films of the 1950s and ’60s, chopped up, scratched up, and drawn anew.

Preserved by Chicago Film Society with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. Laboratory services by Colorlab.

Holiday Magic (1985) – 7 min, 16mm, color, sound

Holiday Magic is an audio-visual collage of discarded material, with 16mm hair care and beauty product commercials overlaid with sound from a promotional record extolling Holiday Magic, a multi-level marketing scheme that hawked cosmetics. McAdams herself described the film as an extended goof (“I tried dubbing the voice of the man on the record into the mouth of some fat dude in a Spanish laxative commercial I had laying around. Lots of bits and pieces of unusual footage are used to further illustrate how ridiculous things can get”) but others saw a more profound statement. Singling out Holiday Magic in his Los Angeles Times column on the occasion of a McAdams show at Filmforum, film critic Kevin Thomas described it as a “deft send-up of the ways in which women in the ’50s and ’60s were made to feel that they must at all times and at all costs maintain an aura of artificial glamour. As we hear pioneer Hollywood makeup artist Perc Westmore drone on about beauty tips, we’re treated to a deliberately jarring collage of stills and lips reminding us of how straitjacketed and lacquered women were unquestionably expected to be in their appearance in the not-so-distant past.”

Preserved by Chicago Film Society with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. Laboratory services by Colorlab.

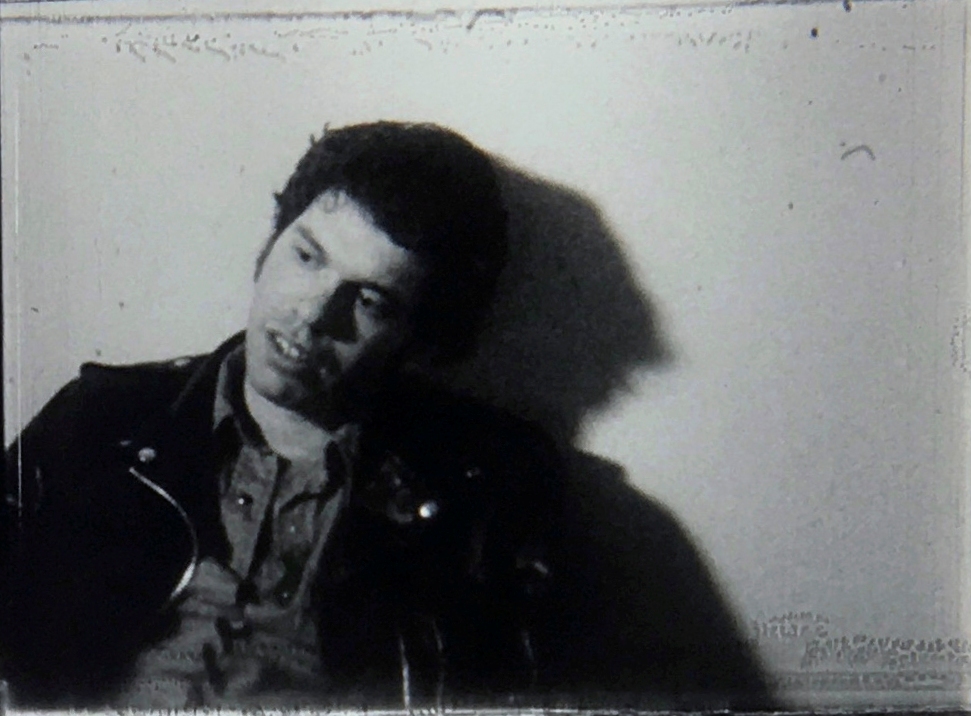

Meet … Bradley Harrison Picklesimer (1988) – 32 min, 16mm, color, sound

McAdams recalled the film’s origins in her notes for the Film-Maker’s Coop catalog: “In 1982, when I first moved to Lexington to teach at the University there, the first thing I remember hearing was ‘you have to meet Bradley Picklesimer!’ Little did I know that I would devote the next three years of my life to making a movie about this Bradley Picklesimer.”

This Bradley Picklesimer was the owner of Club LMNOP, a local drag bar and nightclub on Lexington’s Main Street. He and McAdams became fast friends and she soon found herself spending most weekends at Club LMNOP, shooting drag performances and interviewing its effusive and opinionated proprietor. Her plan was a five-minute film about the Lexington club scene. “People in this country just don’t understand that this stuff is going on in Kentucky,” she later said. “They think it’s all horses and bourbon and basketball, when in fact there’s all sorts of really wild activity. I thought of myself as a journalist.”

Yet McAdams’s central subject could not be contained in a quick journalistic sketch. Speaking into a tape recorder with interviewer Ed Andrews, self-described “redneck in sheep’s clothing” Picklesimer freely recounted his childhood, explained his business, defended Joan Crawford against the charges in Mommie Dearest, and expounded at length about his art. Though he was himself only in his late twenties at the time, Picklesimer complained at length about a younger generation approaching drag and queerness from the wrong angle. In his conception of drag, Picklesimer rejected hormones and implants and emphasized the pleasure of gender-bending performance for its own sake: “They’re not transsexuals, they’re entertainers. The only thing they live for is that moment of looking beautiful and having people applaud that. The shows themselves are hard work to orchestrate, but when it’s good, when a performer can lip sync over a record and bring a crowd to its feet, screaming and yelling for three dollars on a Wednesday night in the middle of Lexington, Kentucky, you know, you get a chill.”

McAdams’s intent and approach shifted as the project grew. “I wanted this film to be like some kind of weird window into Bradley’s world with my target audience being those who are too prejudiced to let themselves ever get to know someone who was a drag queen,” wrote McAdams. “My original intention was to introduce my audience to this colorful personality who I found to be both entertaining and deep. It made me angry that many people would stereotype Bradley because he was a cross dresser, or completely dismiss him altogether as someone who they didn’t want to get to know. I felt that Bradley’s observations about the world were really not that much different than my own, even though our backgrounds and lifestyles were miles apart.”

But any narrow attempt to make a consciousness-raising advocacy documentary was soon frustrated and overtaken by events: Picklesimer lost his bar, became homeless, and moved to West Palm Beach. What began as a relatively simple documentary portrait had grown into something rangier, stranger, and sadder, and McAdams had to adjust her working methods accordingly. As she later recalled in an artist’s statement, “This is my longest and most ambitious film to date and the first time I’ve incorporated things like sync sound, lip dubbing, and superimposed titles. I even traveled with a hired assistant to shoot scenes of Bradley in West Palm Beach, Florida. These were big moves for me considering I usually shoot water boiling on my stove, my face in the mirror, or window shots of my landlady emptying her garbage in the alley. This film really got me out of the house.”

Preserved by Chicago Film Society through the National Film Preservation Foundation’s Avant-Garde Masters program and the Film Foundation. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. Laboratory services: Colorlab, Simon Daniel Sound

Fetal Pig Anatomy (1989) – 7 min, 16mm, color, sound

A montage of atrocities, from atomic test footage to the dissection of the titular pig salvaged from a Boston University educational film. The apocalyptic tone reflects McAdams’s life-long vegetarianism, a frequent subject of her cartoons.

McAdams recalled the film’s unusual production: “The soundtrack was not made specifically for the film; my friend Billy DesJardins came over one night and just slapped it in my tape recorder. I had been working on editing this found footage and ended up watching the film to this tape and thought it was pretty powerful stuff. It’s interesting that I was living right on the ocean in Rhode Island when I was doing all this. It was such a fantastically beautiful environment to live in and there I was in my little beach house, making such a horrific, angry, little film.”

Preserved by Chicago Film Society with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. Laboratory services by Colorlab.

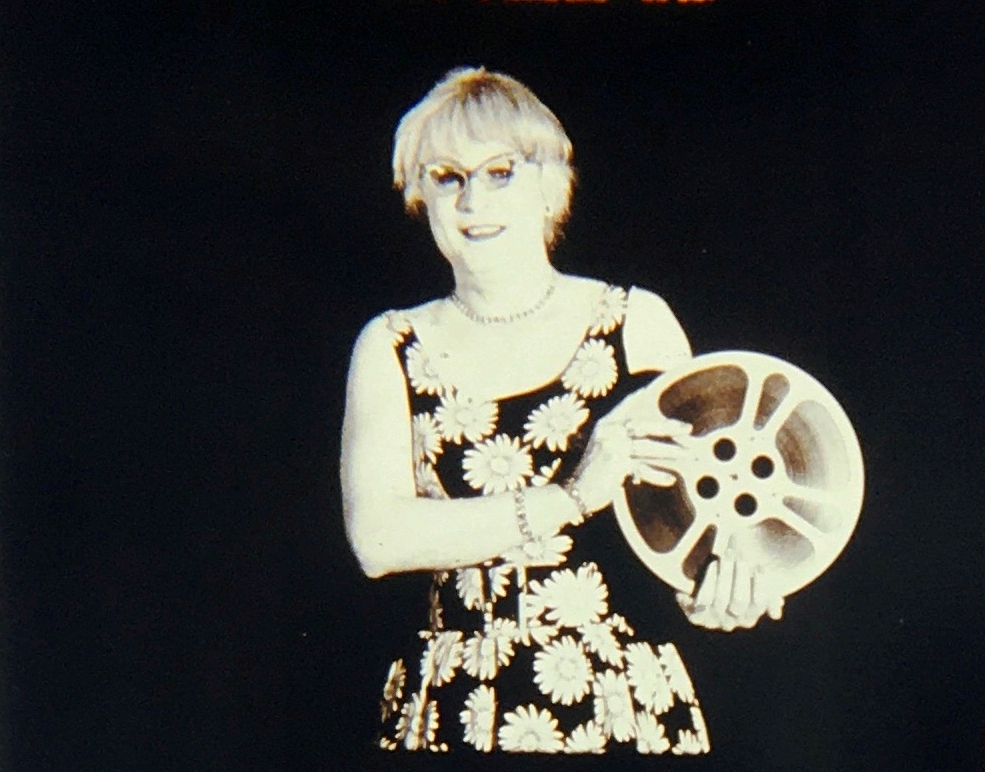

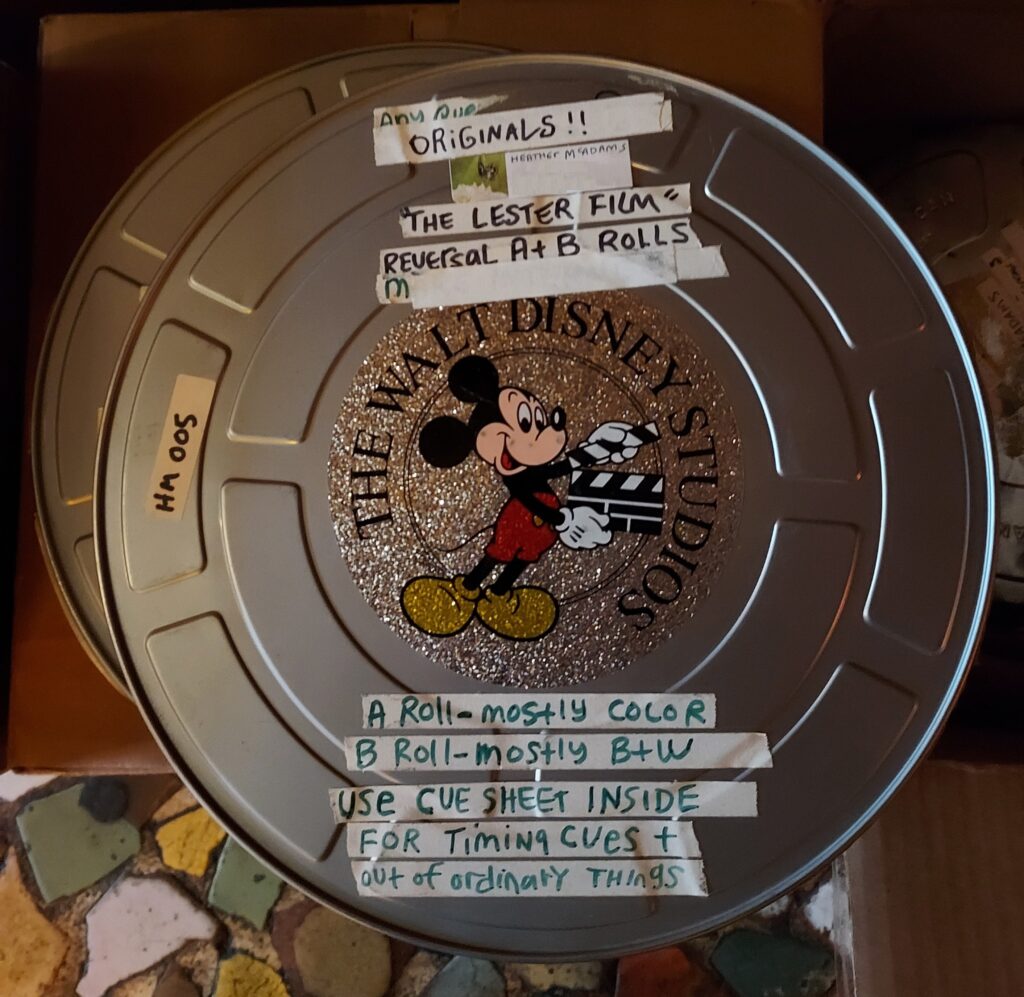

The Lester Film (1995) – 14 min, 16mm, color, sound

Co-directed by Heather McAdams & Chris Ligon

An experimental profile of Chicago painter, rock musician, art therapist, and drag performer Lester Brodzik, aka Lestushka. Brodzik recounts his Chicago childhood (with a special emphasis on the locally-famous hot dog stand Superdawg) and his evolving relationship to gender as a cross-dressing, straight-identifying man, which placed him on the margins of multiple communities.

The film stresses the importance of letting Brodzik tell his own story in all its complex contradictions, with Lester and Lestushka engaging in a tug of war with a 16mm film reel in several scenes. “Working as an art therapist at a mental institution by day and hitting the clubs at night, Lester has gained notoriety for his interesting fashion sense,” wrote McAdams and Ligon. “We especially wanted to capture him on film in the little German girl outfit because no one else would.”

Preserved by Chicago Film Society with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. Laboratory services by Colorlab.

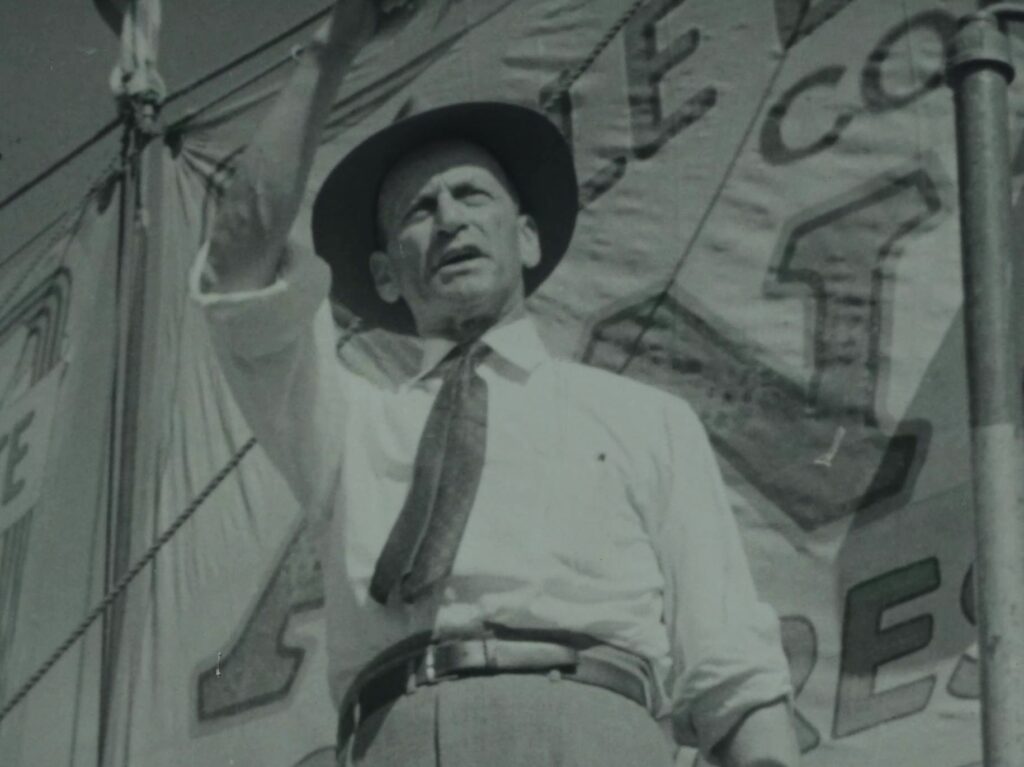

Comes to a Point Like an Ice-Cream Cone (1997) – 18 min, 16mm, color, sound

Co-directed by Heather McAdams & Chris Ligon

This experimental documentary about the sideshow and carnival culture of the early 20th century is composed largely of archival footage from the Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin. “We were able to borrow selected films and optically print from them, selecting images of clowns, circus acts and sideshow attractions,” McAdams recalled. “Sometimes these images were only seconds long, so slowing them down allowed for better viewing & manipulating them for artistic effect became a labor of love .… I believe this limitation is the strength of the film as it forced us into coming up with more inventive and sometimes more humorous solutions that under other circumstances we would never have come up with.”

Preserved by Chicago Film Society with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. Laboratory services by Colorlab.

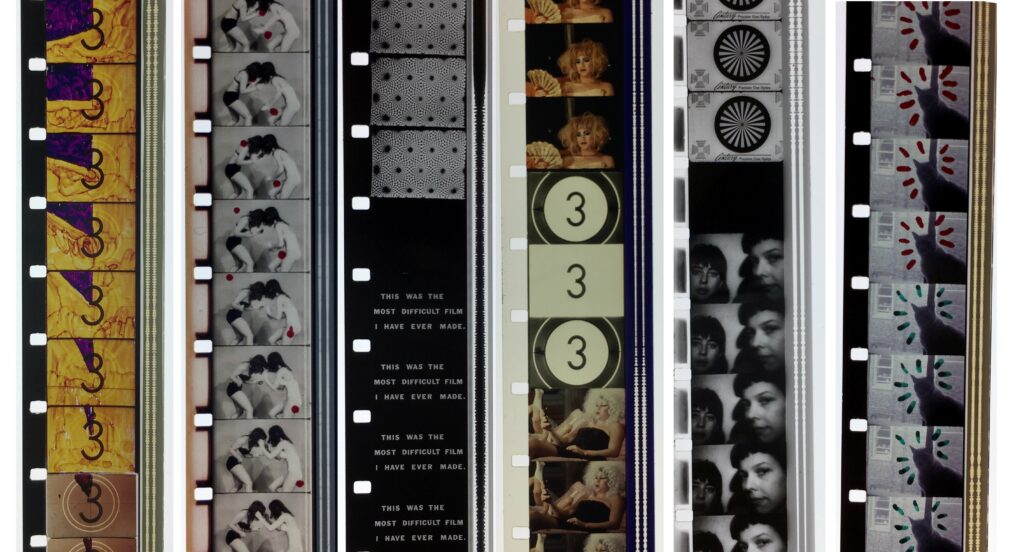

ABOUT THE RESTORATIONS

Heather McAdams has produced more than two dozen films over her career. The great majority of her films incorporate found footage and are largely assembled from vintage prints. It is not uncommon for a single film to incorporate Ektachrome reversal material shot by McAdams, clips from vintage Kodachrome, Eastmancolor, and black-and-white prints from her collection, and sections of hand-painted or otherwise-manipulated footage. When McAdams finished editing a film, she would often order reversal prints for exhibition. Whenever funds were available, she would later make internegatives from her originals for backup. Both the originals and the protection elements were invariably acetate.

The aim of this project was to begin the process of making 16mm polyester internegatives from McAdams’s original master positive elements and new 16mm prints.

McAdams’s films carry a date of completion, but this date can be misleading from a preservation perspective. A film from 1985 is, in truth, assembled from black-and-white educational films of the 1940s, Kodachrome home movies from the 1950s, an Eastmancolor advertising film from the 1960s, and Ektachrome footage from the 1970s and ’80s. Although there are some optically-printed shots here and there, McAdams often worked directly with original prints and re-edited them without creating dupes. In effect, a restoration must re-create how each of these shots looked when McAdams assembled the master positive in 1985, even as different stocks have faded, shrunken, and deteriorated at different rates by 2024. Creating a one-light internegative through traditional photochemical means would not have allowed individual shots to be corrected and adjusted to the degree necessary.

All the films had some hand-manipulated elements (often scratching, but also hand-painting and assorted ink-and-paint defacements) that made liquid gate scanning a practical, technical, and moral impossibility. Though McAdams’s film often look ragged, as if assembled from remnants of a celluloid garage sale, she kept her originals in good condition, with minimal surface damage or abrasion. Drygate scans of her original elements often looked as clean as Ektachrome reversal prints produced three or four decades ago. We opted not to order any further digital cleanup, which would simply not reflect the original materials or McAdams’s aesthetic.

Our aim throughout was simply to produce the sharpest, most accurate rendering of McAdams’s films, with color that accurately reflected the various stocks and emulsions that went into her cornucopia of found footage.

The workflow for all eight films entailed scanning McAdams’s original master positives in 4K, and scanning reference prints (often vintage reversal prints with excellent color retention) to determine the proper color-timing for each shot and sequence. As these films are often dubbed over with music and dialogue from other sources, these vintage prints were also crucial for verifying sound synchronization. Although prior internegatives were examined and occasionally scanned, almost all of these existing protection elements were deemed substandard and flat–and largely unnecessary when McAdams’s original were extant.

Colorlab performed all scanning, conforming, and color correction, which was approved by McAdams and staff from CFS.