Artist, scholar, and teacher Fred Camper (b. Chicago, 1947) has been a well-known and influential member of the avant-garde cinema scene since the late 1960s. Camper established his reputation with articles that appeared in Film Culture, Cinema, and Screen. In Chicago, he reviewed films and art exhibitions in the Chicago Reader, the city’s major alternative weekly newspaper, from 1986 to 2010. His criticism has also appeared in Millennium Film Journal, Artforum, ArtNews, Motion Picture, and the Soho Weekly News, and has been translated into eleven languages. Camper has advocated for the work of many avant-garde filmmakers (most prominently Stan Brakhage, Robert Breer, and Christopher Maclaine), publishing overviews of their career and organizing public and private screenings of their films. In recent years, Camper has been teaching regular courses at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Columbia College Chicago and exhibiting his own digital artwork at galleries in Chicago, New York, and Venice, California.

Less well-known are the 16mm films that Camper made in the late 1960s:

* Joan Goes to Misery (1967)

* A Sense of the Past (1967)

* Dan Potter (1968)

* Welcome to Come (1968)

* Bathroom (1969)

Taken together, the films present a rare opportunity to discover artistic efforts of a prominent avant-garde critic. Camper is also one of the few avant-garde filmmakers who proudly cites Hollywood aesthetics not as a toxic influence to be purged but as a productive avenue of investigation. (He has published as much writing on classical Hollywood and other forms of narrative cinema as on avant-garde film.) Camper’s films reflect an expansive and heterodox sensibility broadens the history of experimental film.

Background

Fred Camper’s filmmaking grew out of his dual interests in the New American Cinema and the emerging auteurist canon. Upon seeing his first avant-garde film, Gregory Markopolous’s Twice a Man, at the age of fifteen, Camper recognized something new and alluring: “Its color had a sensuality I hadn’t imagined possible in film, and its rapid, time-crossing editing was unlike anything I’d seen before. At the time I was interested in mathematics, physics, astronomy, poetry, and classical music. I had grown up without a television, and almost never went to movies.” Camper found guidance for his newfound interest in Film Culture, especially Andrew Sarris’s survey of American auteurs (Hitchcock, Hawks, Fuller, et al.) in Film Culture 28.

While an undergraduate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in early 1965, Camper co-founded the M.I.T. Film Society, which allowed him to see a wide range of films and develop his critical writing through weekly program notes. Camper’s notes on Stan Brakhage’s The Art of Vision were received warmly by Brakhage, who encouraged him to submit them to Film Culture. The magazine published the notes, along with critical pieces on George Landow and Ron Rice. He subsequently published articles on Douglas Sirk in the British magazine Screen.

In late 1965, Camper began working as a laboratory technician in a radiation testing facility. Although his income was modest, he managed to finance a range of 16mm filmmaking efforts.

Camper’s five finished works were all briefly available through Canyon Cinema and included in the cooperative’s second catalog; A Sense of the Past was also available through Audio Film Center (subsequently Audio-Brandon) and the Film-makers Coop. The shorter works (Joan Goes to Misery, A Sense of the Past, Welcome to Come) received scattered rentals, while the two longer and more challenging works, Dan Potter and Bathroom, were never rented. Camper withdrew all of his films from circulation when Canyon instituted an annual fee for unrented titles in the mid-1970s.

Given their limited distribution, Camper’s films have screened rarely—and even more rarely as a corpus. Harvard Film Studies presented his 16mm films in 1968 and 1969, as they were finished. Camper’s complete film works (including the 1984 Super-8 feature SN) screened together for the first time in 2011, when curator Patrick Friel presented two programs under his White Light Cinema banner in Chicago. “While these five films were made by Fred Camper in his early 20s, they are by no means a ‘young person’s’ work,” Friel writes. “Rather, they are highly articulate and distinctive films that move well beyond any notion of influence. In many respects, they are unlike anything I’ve seen from the period, Dan Potter and Bathroom in particular. Each is individually great; taken together, they anticipate aspects of Camper’s later feature-length masterpiece SN and his more recent digital artwork.”

The Films

Joan Goes to Misery (1967, 8 min, 16mm, color, sound, 24 fps)

“Both a “short story” — a film about a girl who rejects “reality” to live in her own private world — and a film about progressive states of mind. Joan goes to a two-room apartment, removes wigs, false eyelashes, makeup; depressed at her own appearance, she lies on the bed and over-eats. The soundtrack (“It’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to …”) adds irony to her “orgy.” But it is her isolation from human contact, and her entrance into a self-indulgent fantasy world that are central “themes” of the film. – Fred Camper, Canyon Cinema Cooperative Catalog No. 2 (1969)

In 1967, a young Fred Camper was offered a chance to discuss current trends in avant-garde cinema on a television talk show hosted by the Li’l Abner cartoonist Al Capp, who had recently developed a sideline in decrying the excesses of campus politics and youth culture. The show was shot in Boston but syndicated nationally. Camper’s insightful and articulate defense of avant-garde cinema prompted the show’s producers to make an odd proposal: they would give Camper the money to produce an avant-garde film of his own, which would air as part of a future episode.

The commission was open-ended and loose; the only requirement was that the film address the topic of ‘misery,’ perhaps an indication of how dour and self-involved the skeptical producers presumed the typical avant-garde film to be. The station would pay for the camera stock and processing, but Camper would be responsible for the cost of making any additional prints.

Utilizing his friends Joan Tollentino and Michael Prokosch as actors, Camper made an eight-minute film on Ektachrome ER reversal stock, with a few moments of post-dubbed sync sound. Satisfied with the film, Camper brought it back to the TV station. They booked a return appearance from Camper and scheduled the film.

The airing did not go as the filmmaker anticipated. “The TV station aired a version of Joan that was half the running time of my film,” Camper recalled. “It had a similar sound track, but my sound track was completely re-recorded and re-synced. They also aired it, perhaps I should add, with a comic who was a guest on this variety show doing a sarcastic voiceover. Most of the film is silent. I think he started, over the fairly conventional opening establishing shot without much action, with something like ‘Oh, this is good.’ Their idea was to get me angry and produce an entertaining confrontation. It didn’t work.”

Despite this set-back, Camper was free to disseminate his proper version of Joan Goes to Misery however he saw fit. He left the film in care of two West Coast distributors—Canyon Cinema and Audio Film Center—and it received a few bookings, as well as a notice in the underground newspaper Berkeley Barb from filmmaker and filmmaking instructor Lenny Lipton: “The grooviest part of Joan is the color, which is swirly-grain-indoor-sunset … The free elements, home movie elements, that I can isolate in Joan, are jump cutting, and the colors. Joan, as a character study, is completely believable. It rings right.”

Joan Goes to Misery has been preserved by Chicago Film Society. Laboratory services by Colorlab and DJ Audio, Inc. A new 16mm internegative was created from the original Ektachrome ER reversal master positive; a re-recorded 16mm optical track negative was created from the original magnetic master.

A Sense of the Past (1967, 4 minutes, 16mm, color, silent, 16 fps)

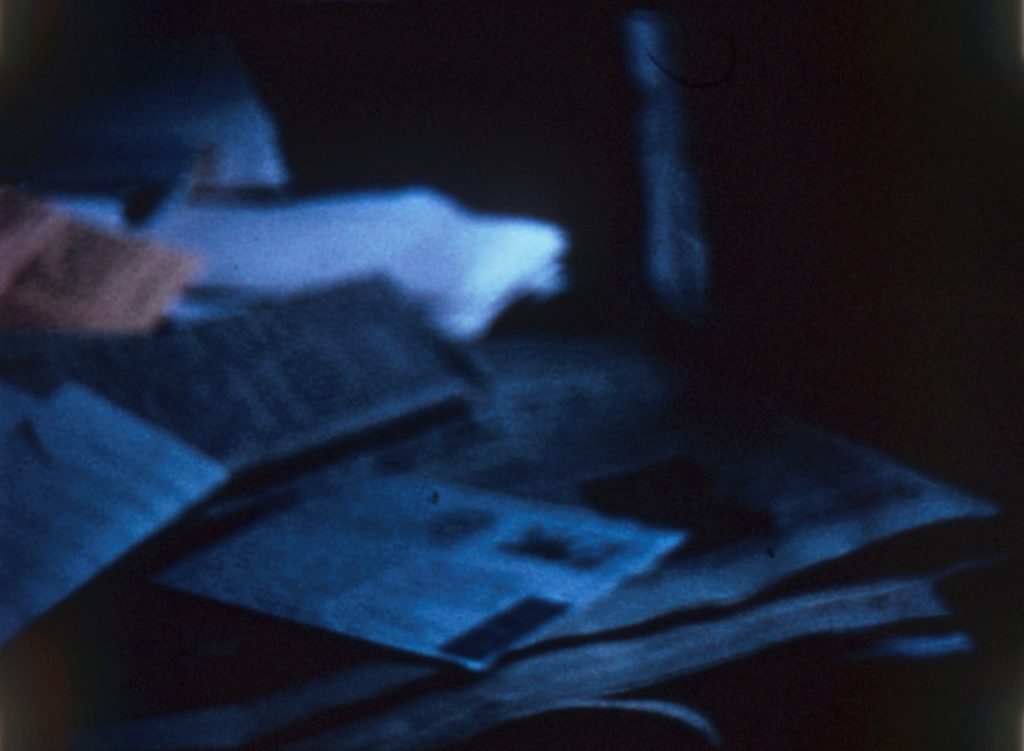

“A short film description of a room, and several of the objects and light patterns in it. With the use of color, camera movement, and cutting, I’ve tried to create a feel of restfulness and silence; and at the time a hint of other, darker elements; a sense of a violent – though not fully visible – past.” – Fred Camper, Canyon Cinema Cooperative Catalog No. 2 (1969)

This short work is an explicit homage to the films of Stan Brakhage. (The titles are even scratched in black leader à la Brakhage.) Largely a fragmentary exploration of a shadowy house, its ominous portents are suggested by stacks of old letters piled on a desk. “A Sense of the Past was shot without pre-planning during a long weekend reading Henry James,” recounted Camper, “and I would like to think that its form was somewhat influenced by his passive descriptions that seem to both evoke and conceal great, not fully articulated, traumas.”

A Sense of the Past has been preserved by Chicago Film Society through the National Film Preservation Foundation’s Avant-Garde Masters program and the Film Foundation. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. Colorlab produced a new 16mm internegative using the original A & B rolls.

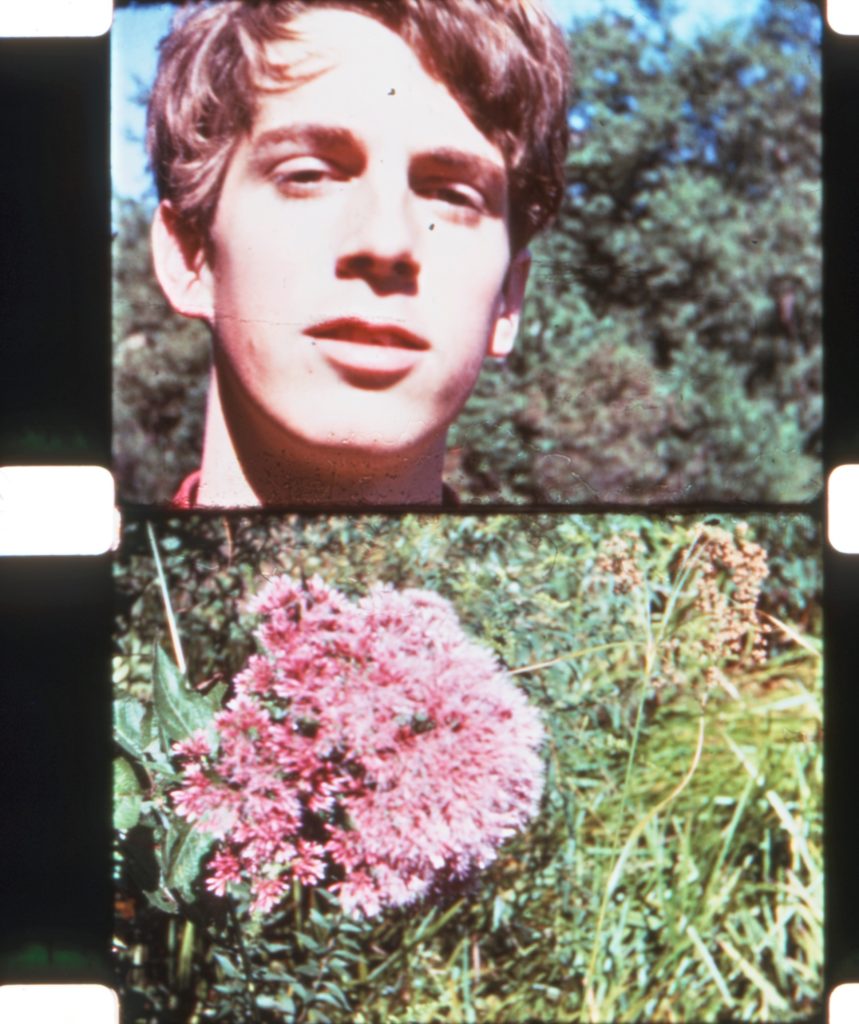

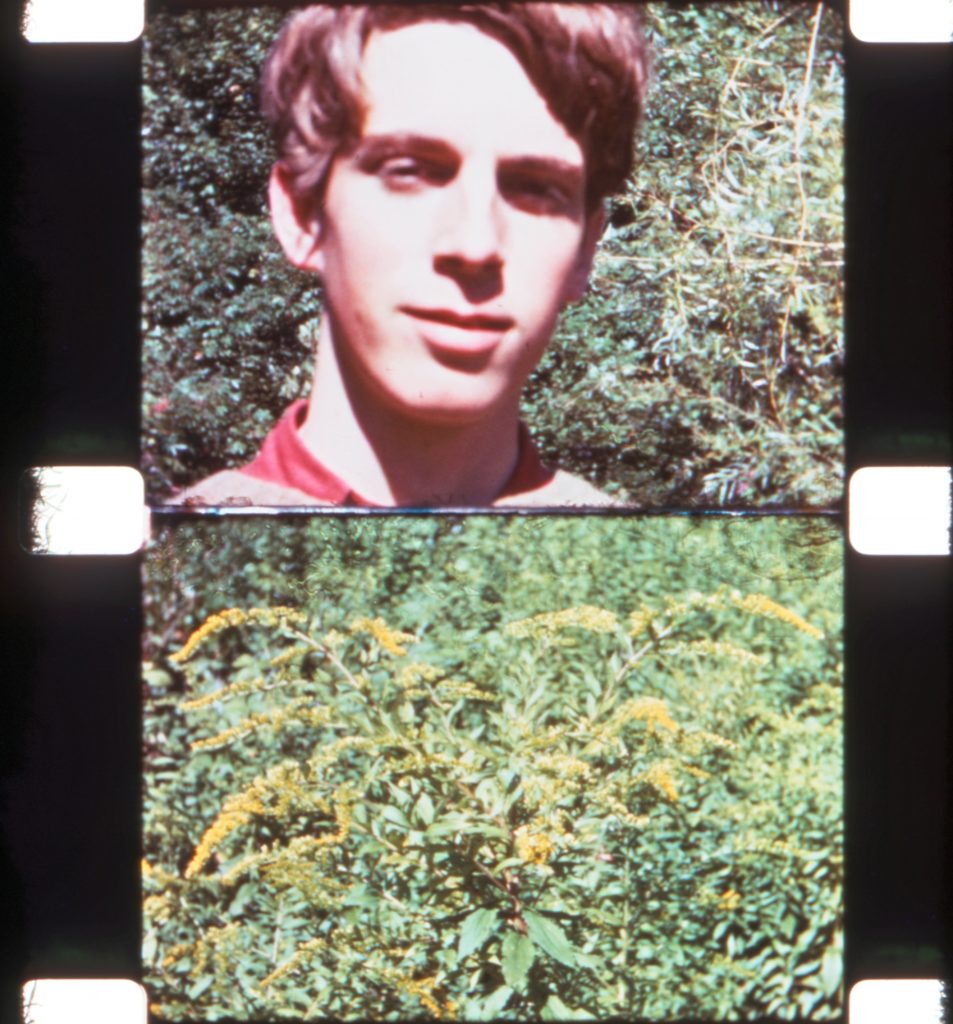

Dan Potter (1968, 39 minutes, 16mm, color, silent, 24 fps)

A study of Camper’s acquaintance Dan Potter and his relation to nature over the course of a year.

“It was made out of a deep feeling for certain kinds of images; for a continuity in which [Dan Potter’s] face would dominate, in which the whole background, the whole world, would be absorbed into his face. Much of the cutting rhythm of the film tries to suspend the passage of time, to give a feeling for the continuous existence of his face. Even his actions are repeated several times, as if to preserve and freeze their existence in time. After the film’s first third, he gradually begins to blend more, physically, with the background of the forest.” – Fred Camper, Canyon Cinema Cooperative Catalog No. 2 (1969)

“Though not a portrait, it was inspired by the way Gregory J. Markopoulos’s portraits in Galaxie intermingle the identities of his figures with objects around them; less obvious influences are F.W. Murnau’s Tabu and the relationships between figures and backgrounds in the films of Howard Hawks.” – Fred Camper, White Light Cinema Program Notes, 2011

Dan Potter has been preserved by Chicago Film Society through the National Film Preservation Foundation. A new 16mm internegative was created from the original A & B rolls by Colorlab.

Welcome to Come (1968, 3 minutes, 16mm, color, sound, 24 fps)

“A long slow zoom from a warm room interior to a close shot of dark blue tree branches seen outside the window. A film about the eye’s ability to move subjectively from one place to a completely different one; about the ability of the imagination to discover and enter ‘other worlds’ hidden amidst the surface clutter of everyday surroundings.” – Fred Camper, Canyon Cinema Cooperative Catalog No. 2 (1969)

Camper’s most popular film, Welcome to Come was rented often and found its way onto several university film syllabi. Camper’s appropriation of the Beach Boys’ 1967 song “You’re Welcome” earned a favorable comparison to Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising from Stuart Byron in the Village Voice in 1973. John Belton bracketed Welcome to Come with Ernie Gehr’s Serene Velocity, Michael Snow’s Wavelength, and Andy Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls as a crucial exemplar of the zoom aesthetic in a 1980 issue of Cineaste. Welcome to Come also garnered praise in more mainstream publications, including a brief notice in Variety and Eric Sherman’s book Directing the Film: Film Directors on Their Art.

Welcome to Come has been preserved by Chicago Film Society through the National Film Preservation Foundation’s Avant-Garde Masters program and the Film Foundation. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. Laboratory services by FotoKem and DJ Audio, Inc. A new 16mm internegative was created from the original Ektachrome EF reversal master positive; a re-recorded 16mm optical track negative was created from a track positive derived from the original track negative.

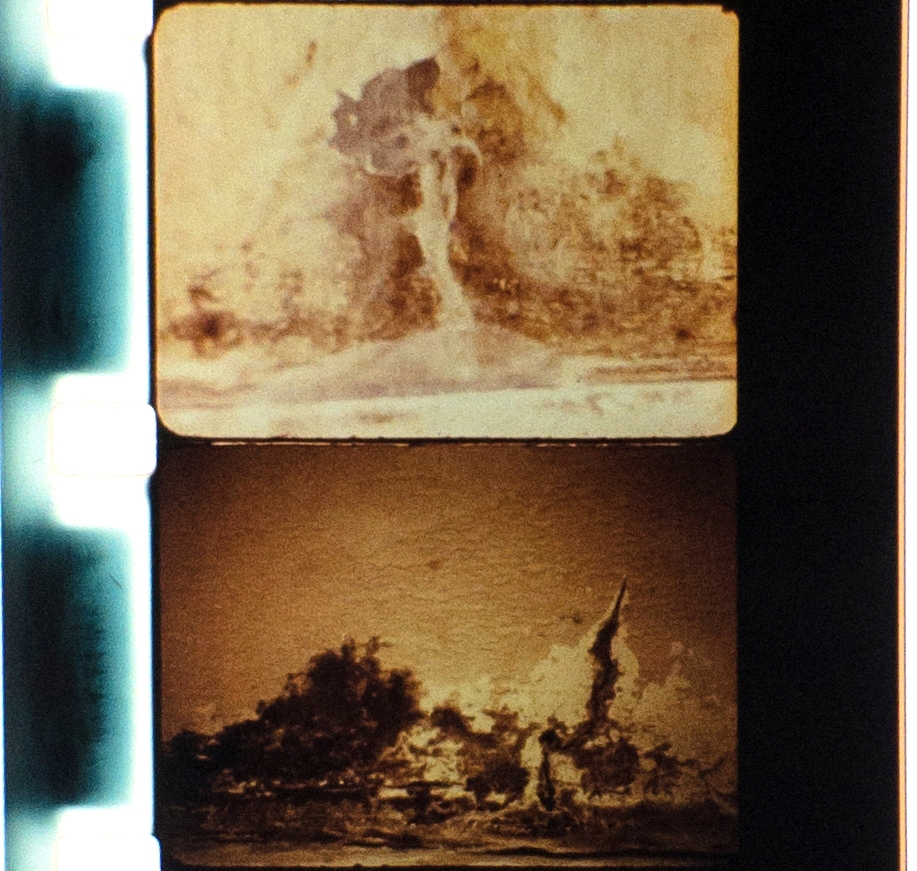

Bathroom (1969, 25 min, 16mm, color, silent, 24 fps)

“Bathroom shows a somewhat seedy bathroom, beginning with a stab at seeing it ‘objectively’ that soon fails; the forms descend into what I hope is a terrifying, even self-destroying irrationality. One inspiration was the long take depiction of madness at the end of Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour; another, the two out-of-focus shots of the altar near the end of Douglas Sirk’s The First Legion.” – Fred Camper, White Light Cinema Program Notes, 2011

Shot in the shared bathroom of the rooming house where Camper lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Bathroom presents a montage of irreconcilable views of the empty room. The focus drifts constantly, with defamiliarized close-ups of the faucet, the toilet, and decaying plaster.

Though Camper found inspiration in work of Hollywood filmmakers, Bathroom points towards a new aesthetic and fits alongside other structural films of the late 1960s and early 1970s, in the vein of Larry Gottheim, Ernie Gehr, Michael Snow, and Hollis Frampton. Bathroom builds a sense of place through the gradual accretion of isolated details–a vision that mines the inexhaustible complexity of even the most quotidian and unadorned of human spaces. In many ways, Camper’s method anticipates the strategy that his friend and mentor Stan Brakhage would apply in his own film Text of Light (1974), an abstract study of light reflected through an ashtray.

Bathroom has been preserved by Chicago Film Society through the National Film Preservation Foundation. A new 16mm internegative was created from the original A & B Etachrome EF reversal camera rolls by Colorlab.