Please be aware of the latest public health guidelines at our partner venues. As of April 1, 2022:

• All visitors to the Music Box Theatre are encouraged to wear masks whenever interacting with staff or not seated in the auditorium. Please read the Music Box COVID guidelines before purchasing tickets.

• All visitors to the Auditorium at NEIU will need to show proof of full vaccination. Masks are still required on the NEIU campus.

Our screenings are held at multiple venues around Chicago. This season you can find us at:

• The Music Box Theatre

3733 N Southport Ave — Directions • Parking • Covid Policies

Tickets: $10 – $12

• The Auditorium at Northeastern Illinois University (NEIU) (inside of Building E)

3701 W Bryn Mawr Ave — Directions • Campus Map • Covid Policies

Tickets: $10

• Chicago Filmmakers

5720 N Ridge Ave — Directions • Parking • Covid Policies

Tickets: $10

• Gene Siskel Film Center

164 N State St — Directions & Parking • Covid Policies

Tickets: $12

Want to attend our screenings but having financial hardships? Contact info@chicagofilmsociety.org

SEASON AT A GLANCE

January & February ▼

Sat 1/29 at 11:30 AM

The Freshman ………… Music Box

Tue 2/1 at 7:00 PM

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai ………… Music Box

Wed 2/9 at 7:30 PM

Rich Kids ………… NEIU

Wed 2/16 at 7:30 PM

The King of Comedy ………… NEIU

Sat 2/19 at 11:30 AM

Fazil ………… Music Box

Wed 2/23 at 7:30 PM

Hallelujah ………… NEIU

March ▼

Wed 3/2 at 7:30 PM

I Saw What You Did ………… NEIU

Wed 3/9 at 7:30 PM

Air Mail ………… NEIU

Mon 3/14 at 7:00 PM

In The Cut ………… Music Box

Sat 3/19 at 11:30 AM

The Crowd ………… Music Box

April & May ▼

Sat 4/2 at 7:00 PM

Sharon Couzin shorts program ………… Chicago Filmmakers

Mon 4/4 at 7:00 PM

Bigger Than Life ………… Music Box

Thu 4/7 at 7:00 PM

In Spring ………… Gene Siskel Film Center

Sat 4/16 at 11:30 AM

The Fire Brigade ………… Music Box

Wed 4/20 at 7:30 PM

The Ballad of Cable Hogue ………… NEIU

Wed 4/27 at 7:30 PM

The Marrying Kind ………… NEIU

Wed 5/4 at 7:30 PM

City Lights ………… NEIU

Add the schedule to your google calendar

Saturday, January 29 @ 11:30 AM / Music Box Theatre

THE FRESHMAN

Directed by Fred Newmeyer and Sam Taylor • 1925

One of the most financially successful pictures of the silent era, The Freshman was, in some ways, an unlikely smash. Although Harold Lloyd was silent comedy’s undisputed box office champion, he had recently cultivated a reputation for death-defying stunts and meticulous chases in films such as Safety Last and Girl Shy. Bereft of daredevil thrills, The Freshman hinges entirely on Lloyd’s hometown charm, an island of wholesome earnestness in a sea of Prohibition-era cynicism. He plays Harold Lamb, a mild-mannered freshman at Tate College who aspires to be Big Man on Campus, but whose only knowledge of college customs comes from the movies. (Though The Freshman was scarcely the first of its genre, more people bought tickets to it than had likely ever stepped foot on a college campus, setting off a wave of student comedy imitators and rip-offs from Buster Keaton to Adam Sandler.) Lamb’s quest to win the girl (Jobyna Ralston) and achieve pigskin glory provides a loose structure upon which Lloyd hangs a series of riotous set pieces, culminating in The Big Game where nothing goes right. Don’t worry—no prior knowledge of football or any other sports is required to enjoy Lloyd’s exquisitely choreographed hijinks. (KW)

76 min • Pathé • 35mm from Harold Lloyd Entertainment

Preceded by: Putnam Family Home Movies (c. 1930s) – 10 min – 16mm

Live musical accompaniment by Music Box house organist Dennis Scott

Tuesday, February 1 @ 7:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

GHOST DOG: THE WAY OF THE SAMURAI

Directed by Jim Jarmusch • 1999

Four years after he twisted the Western inside out with Dead Man, Jarmusch directed Ghost Dog, a mournful take on the crime film with a specific nod to the films of Seijun Suzuki and Jean-Pierre Melville. Ghost Dog is an unknowable mafia contract killer who finds himself the target of his own employers after a hit gone wrong. Played with fierce elegance by Forest Whitaker, he spends his days tending to his carrier pigeons (his only mode of communication with the mob), hanging out with his best friend (a French-speaking ice-cream vendor he can’t understand), and reading the 18th-century warrior philosophical text, Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai, to which he fiercely adheres. Featuring a stuttering, hypnotic score by a 28-year-old Wu-Tang Clan founder RZA (his short cameo likely prompted ’90s teens everywhere to lean over to their neighbor in the darkened theater and whisper… “that’s RZA!”), cinematography by master Robby Müller, and a supporting cast that includes Isaach de Bankolé, Henry Silva, and Cliff Gorman as a Flavor Flav-loving mafioso. Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote upon the film’s release, “It’s such an exciting, prescient, moving, and noble failure that I wouldn’t care to swap it for even three or four modest successes.” After over 20 years the film feels weightier and yes, eerily prescient. “Ancient Japan was a pretty strange place” is a sentiment echoed twice in the film; 2021 is a pretty strange place too. (RL)

116 min • Lionsgate • 35mm from Lionsgate, permission Janus Films

Preceded by: Woody Woodpecker in “Pantry Panic” (Walter Lantz, 1941) – 7 min – 16mm

Wednesday, February 9 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

RICH KIDS

Directed by Robert M. Young • 1979

By the late 1970s, Robert Altman had briefly beaten Hollywood as its own game. Armed with a five-picture directing contract with 20th Century-Fox, Altman set up Lion’s Gate, a production company that would oversee films from his proteges, including Alan Rudolph, Robert Benton, and Robert M. Young. While Altman was making A Perfect Couple and Quintet, Young helmed Rich Kids, an overlooked but totally charming snapshot of family life after the upheaval of the sexual revolution. Franny (Trini Alvarado) and Jamie (Jeremy Levy) may look like privileged teens, but their tony Upper West Side private-school accommodations can’t paper over the low-key chaos of their home lives. His parents are already divorced. (They took him to McDonald’s to break the news, and he’s never been able to enjoy a Big Mac again.) Her parents are separated but ineptly trying to hide it from her. Fed up with the shabby hypocrisy of the adult world, Franny and Jamie sell their parents plausible-sounding lies about sleepovers in Westport and Easthampton and camp out in his dad’s loft, a bachelor man-child playground of exotic animals, jukeboxes, 16mm projectors, and Mechagodzilla paraphernalia. This gentle, precisely observed film plays like an exhausted, end-of-the-’70s echo of Taking Off, complete with a troupe of well-meaning but deeply ineffectual yuppie parents. Rich Kids hit close enough to home on that score to prompt this telling complaint from Gene Siskel: “The adults are a bunch of boobs in this film, especially the men. The woman that wrote this picture [Judith Ross] must not like men, because every one of these guys is an idiot.” Note: This original release print has slightly faded color. (KW)

96 min • Lion’s Gate • 35mm from private collections, permission Park Circus

Preceded by: Daffy Duck in “The Henpecked Duck” (Robert Clampett, 1941) – 8 min – 16mm

Wednesday, February 16 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

THE KING OF COMEDY

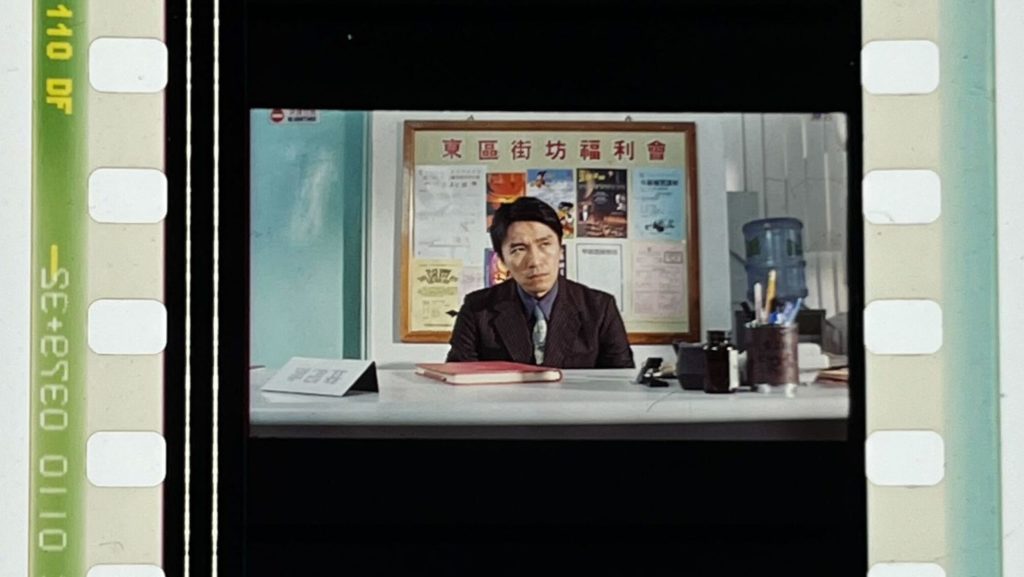

Directed by Stephen Chow & Lee Lik-chi • 1999

In Cantonese with English subtitles

Most audiences in the US first saw Stephen Chow in his CGI-heavy comedies Shaolin Soccer and Kung Fu Hustle, but by that point he was already an international sensation thanks to the steady clip of goofball Cantonese comedies he starred in (and occasionally directed) throughout the ’90s. Chow’s penultimate film of the decade, seemingly conceived as a capstone to his industry-dominating run as a leading man, The King of Comedy is perhaps the sweetest and most broadly accessible movie he ever made, the kind of scrappy “let’s put on a show!” revue that’s been charming audiences as long as people have been watching movies. Chow stars as a Z-grade acting instructor and thoroughly disliked bit player with his heart set on becoming a movie star, even as his acting abilities fall short of his ambitions. While his dedication isn’t enough to earn him the catered set lunch he so desperately covets, he finds an unexpected outlet for his talents in teaching everyday performance lessons to his deranged neighbors (including a nerdy gangster whose boss wants him to act tougher and a gorgeous prostitute whose inability to hide her disgust with men drives away all potential clients). Coming at the tail end of Hong Kong cinema’s golden age and packed with cameos from every major star of the era, The King of Comedy is a winning send-off not just for Chow’s star persona but also for one of the greatest pop cinemas to ever exist. (CW)

90 min • The Star Overseas Ltd. • 35mm from Chicago Film Society collections

Not available on disc or streaming!

Preceded by: Laurel & Hardy in “A Day at the Studio” (Edward Sedgwick, 1937) – 8 min – 16mm

Saturday, February 19 @ 11:30 AM / Music Box Theatre

FAZIL

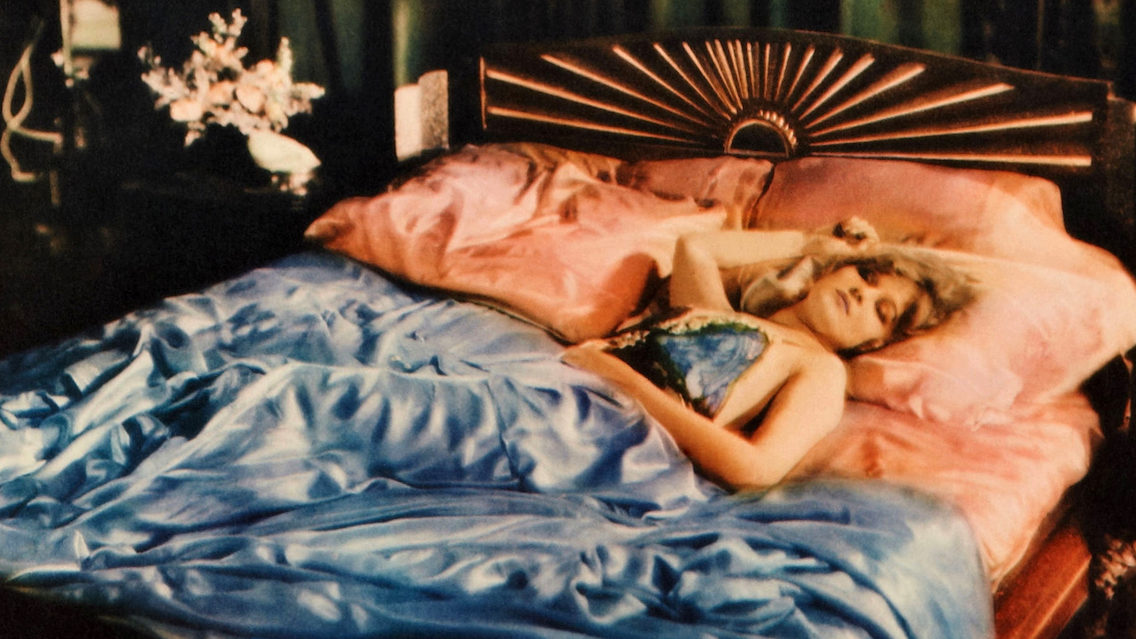

Directed by Howard Hawks • 1928

Officially, Fazil is an adaptation of Pierre Frondaie’s 1922 play L’Insoumise, but not because Hollywood was actively scouting the French boulevard for source material. The film really owes its existence to the ostensible posthumous box office power of prototypical heartthrob Rudolph Valentino. As star of The Sheik and Son of the Sheik, Valentino had fired up demand for bodice-tearing desert pictures, and Fox hoped that the embers could still be stoked even two years after his death. Variety assured exhibitors that Fazil might look like a ho-hum ‘woman’s picture,’ but boasted “large and liberal doses of good solid box office sex and sheik stuff.” Charles Farrell stars as Prince Fazil, an Arabian potentate who must reconcile his resolutely traditional ways with the more liberated mores of his new Parisian wife, Fabienne (Greta Nissen). Can Europe’s swankiest night clubs compete with a desert harem? Fazil is assuredly an outlier in the filmography of director Howard Hawks, who only took the studio assignment reluctantly. Hawks fancier Dave Kehr observed that the director “seems to be experimenting with a gauzy, Sternbergian style … totally at odds with his pragmatic personality,” but who wants pragmatism when a beautifully designed, saucy continental fable is on offer? Fox sold Fazil as “Hot as Sahara,” and it remains a naughty vision of culture clash and changing sexual mores. Preserved by the Museum of Modern Art. (KW)

75 min • Fox Film Corp • 16mm from the Museum of Modern Art, permission Disney

Not available on disc or streaming!

Preceded by: Laurel & Hardy in “Bacon Grabbers” (Lewis R. Foster, 1929) – 20 min – 16mm

Live musical accompaniment by Music Box house organist Dennis Scott

Wednesday, February 23 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

HALLELUJAH

Directed by King Vidor • 1929

A pioneering work of sound cinema and a landmark musical, Hallelujah is, above all, a movie of seemingly stark contradictions. It’s Hollywood’s first movie with an all-Black cast, though it was planned and produced by a white crew. Its story of spiritual degradation and rebirth in the cotton fields is told through a soundtrack that mixes traditional spirituals (“Get on Board Little Children,” “Go Down Moses”) with Tin Pan Alley imitations penned by Irving Berlin (“Swanee Shuffle,” “Waiting at the End of the Road”). It is a marvelous showcase for Black Broadway talent, including Daniel L. Haynes and Nina Mae McKinney, though their characters are conceived through admittedly stereotypical lenses. (Haynes stars as Zeke, a sharecropper who succumbs to deadly temptation in the form of Chick, McKinney’s juke joint siren; after accidentally killing his own brother, Zeke sets out to reform his life, becoming a Baptist preacher and delivering the good news to the cotton fields.) It is among the most technically and aesthetically innovative sound movies of its era, though it achieved this dynamism by recording its location footage without cumbersome sound equipment, dubbing in music and dialogue later in studio. Hallelujah is both experimental and risky by the standards of M-G-M, and a very Hollywood-ized rendition of its own story. Edited down for a reissue in the late 1930s, Hallelujah has been newly reconstructed to better approximate the original 1929 release version, allowing us to contemplate and enjoy this strange creation anew. Restored by the Library of Congress and The Film Foundation. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. (KW).

100 min • Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer • 35mm from Library of Congress, permission WB/Swank

Preceded by: Nina Mae McKinney in “Pie, Pie, Blackbird” (Roy Mack, 1932) – 11 min – 16mm

Wednesday, March 2 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

I SAW WHAT YOU DID

Directed by William Castle • 1965

By the time he got around to making I Saw What You Did, horror impresario and one-man amusement park William Castle had already exhausted some of his best gimmicks: the Punishment Poll, the Fright Break, Percepto. The gimmick he devised for this one was admittedly half-assed (seat belts to keep folks from falling to the floor in fright) but the film itself boasted a crackerjack premise: teen queen Libby (Ann Garrett) is holed up with her best friend Kit (Sarah Lane) at her parents’ glamorous ranch house in the middle of nowhere. They’re joined by Libby’s little sister, Tess, who periodically insists “I’m normal!” with a sense of real striving. The trio start making prank calls to random losers in the phone book, and eventually settle on “I saw what you did and I know who you are” as an all-purpose greeting. Problem is, they try this line on John Ireland, who’s just stabbed his wife to death and doesn’t want anyone to know who he is or what he did. Top-billed Joan Crawford plays the bejeweled spinster neighbor who tries to bag herself a homicidal husband, but she’s upstaged by the nasty naturalism of the kids, who aspire to be mean girl versions of Hayley Mills in an off-brand Disney picture. (KW)

82 min • Universal International • 35mm from Universal

Preceded by: “Safety in the Home, 2nd edition” (Encyclopedia Britannica Films, 1951) -13 min – 16mm

Wednesday, March 9 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

AIR MAIL

Directed by John Ford • 1932

Hard to believe now, but there was once a time when major studios would actually bankroll white-knuckle action cinema focused on the routine work done by civil service employees. A terse, bitter precursor to aviation dramas like Only Angels Have Wings, Air Mail marshaled John Ford’s proven skills as a director of rough-and-tumble set pieces and a whole squadron of nonunion stunt pilots to bring to life the daily dramas occurring around a small Rocky Mountain airstrip which plays host to the US Postal Service. Ralph Bellamy stars as the overseer of a crew of misfits entrusted to deliver air mail, disclaiming passenger runs, clashing with his new hotshot employee (played with Teflon sliminess by our favorite pre-Code asshole Pat O’Brien), and flying the rounds himself whenever one of his pilots makes a crash landing. Ford’s only film shot by master cinematographer Karl Freund (whose work on Sunrise would provide vital inspiration for the director throughout his career), Air Mail complements the hard-bitten masculine melodramatics of its ground scenes with unparalleled aerial stunt work and enough pre-Code seaminess to make you realize just how sexy delivering the mail is. (CW)

84 min • Universal Pictures • 35mm from Universal

Not available on disc or streaming!

Preceded by: “Our Post Office” (Encyclopedia Britannica Films, 1956) – 10 min – 16mm

Monday, March 14 @ 7:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

IN THE CUT

Directed by Jane Campion • 2003

When respected art house heavyweight Jane Campion made a foray into genre filmmaking with an erotic thriller starring none other than rom-com queen Meg Ryan, it was met mostly with confusion, albeit not by everyone — Manohla Dargis cannily raved, “Jane Campion’s astonishingly beautiful new film may be the most maddening and imperfect great movie of the year.” Though it was based on Susanna Moore’s 1995 novel and pitched to investors as serial killer romp à la David Fincher’s Se7en, you’d be hard-pressed to find anything the two films have in common except a predilection for severed body parts in surprise locations. Ryan may be at her finest as a dour English teacher pulling a rolling suitcase behind her as she stalks the streets of the Lower East Side looking for thrills. After one of her afternoon dive bar visits plunges her into a brutal murder case, she becomes sexually involved with the brooding homicide detective (Mark Ruffalo at peak steaminess), who may not be who he claims. Dion Beebe’s gauzy and often garish cinematography (he would later work on Michael Mann’s Collateral and Miami Vice) helps transform New York into a sleazy dreamscape, and scene stealer Jennifer Jason Leigh co-stars as Ryan’s vulnerable half-sister. Campion imbues what might have just been another voyeuristic erotic thriller in other hands with startling intimacy, resulting in a film both brutal and delicate, and ready for rediscovery. (RL)

119 min • Screen Gems • 35mm from Sony Pictures Repertory

Preceded by: Meg Ryan Trailer Reel – 35mm

Saturday, March 19 @ 11:30 AM / Music Box Theatre

THE CROWD

Directed by King Vidor • 1928

John Sims’s life begins auspiciously enough, born on the fourth of July at the dawn of a new century, his father confidently predicting big things for his future. Just two scenes later, an adolescent John is grieving Dad’s premature death, an early sign of the pains and frustrations to come. In the entertainment industry, quotidian disappointment has never made for boffo business, and it was only thanks to the success of his war epic The Big Parade (one of the highest grossing films ever at the time) that director and writer King Vidor was able to get a project as decidedly unconventional as The Crowd bankrolled by a major studio. Vidor proceeds to follow his ostensible hero (James Murray, purposely selected like much of the cast for being unknown) through the kind of scattered milestones (marriage, children, fleeting professional success), squandered opportunities, and personal tragedies that make up most of our lives. Taking a page from his artier European contemporaries’ recent stylistic experiments, Vidor envisioned The Crowd’s comparatively mundane narrative as an expressionist tour de force, throwing in some proto-vérité location scenes and bombastic mobile camerawork to prove the common dramas of daily life make for cinema as compelling as anything out there. (CW)

102 min • Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer • 35mm from Warner Bros.

Not available on disc or streaming!

Preceded by: “Canned Thrills” (John L. Hawkinson, 1927) – 7 min – 16mm

Live musical accompaniment by Music Box house organist Dennis Scott

Saturday, April 2 @ 7:00 PM / Chicago Filmmakers

Sharon Couzin Shorts Program

It’s a pretty certain thing film culture in Chicago today would be totally different if it weren’t for Sharon Couzin. As the long-serving chair of SAIC’s film department and a founding figure in the Experimental Film Coalition and its offshoot Onion City Film Festival, Couzin’s impact on the avant-garde film community across the Midwest as an organizer and mentor was immeasurable. She was also a preternaturally gifted filmmaker, specializing in densely layered, optically printed compositions and expressionistic images of femininity across the score of bewitching, dreamy, and disquieting shorts she started making in the mid-’70s. Despite being an internationally acclaimed experimental film scene fixture throughout her filmmaking career, her work has been difficult to see in recent years, even here in the city where most of it was made. We’re bringing a selection of Couzin’s films back to the festival she was instrumental in founding, including a new 16mm restoration of her breakthrough film Roseblood (1974) alongside her acclaimed shorts A Trojan House (1981), Shells & Rushes (1987), and more. (CW)

Approx run time 65 min • 16mm from Canyon Cinema

Not available on disc or streaming!

Presented as part of the Onion City Experimental Film & Video Festival (running March 31 – April 3)

Monday, April 4 @ 7:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

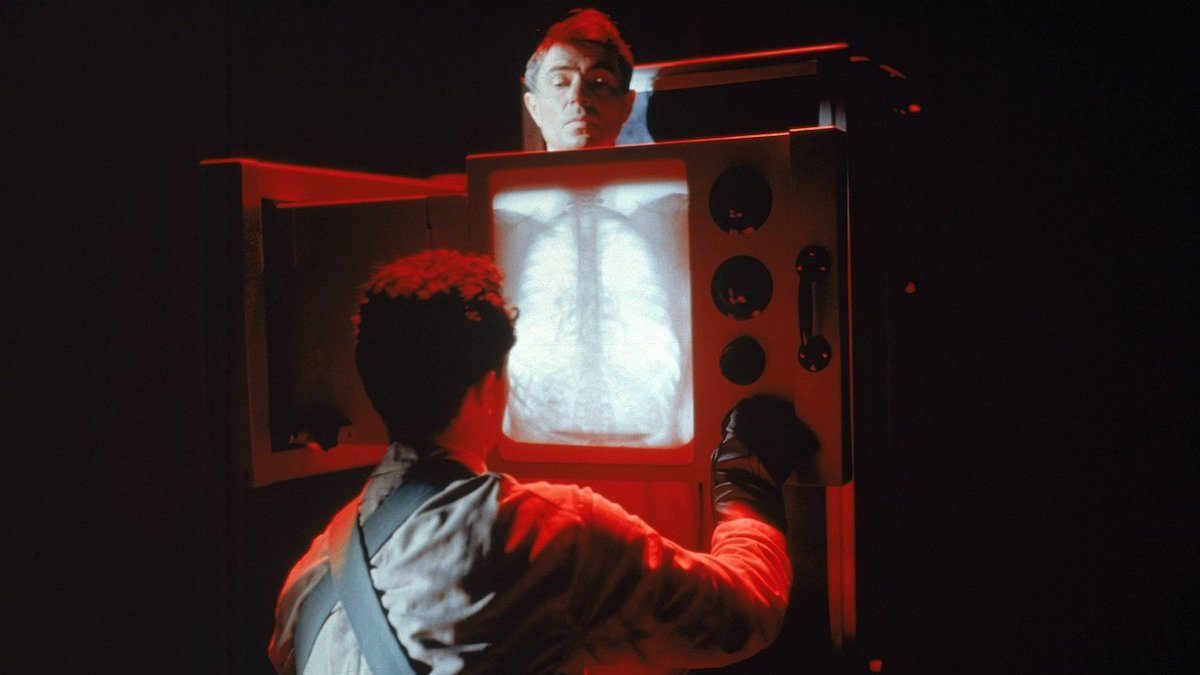

BIGGER THAN LIFE

Directed by Nicholas Ray • 1956

Long after Technirama and Superscope were consigned to history books, the anamorphic widescreen process developed at 20th Century-Fox and branded as CinemaScope still remains synonymous for most cinephiles with cinematic grandeur. The first years of CinemaScope were overwhelmingly flush with biblical epics, Westerns, and other genre films heavy on visual splendor, but the format’s early days also saw maverick directors like Vincente Minnelli and Henri-Georges Clouzot using the extra-wide canvas for projects far more personal and idiosyncratic than King Richard and the Crusaders. An adaptation of a New Yorker article about cortisone-induced psychosis, Nicholas Ray’s Bigger Than Life, maybe more than any other film the era produced, seems an especially strange candidate for CinemaScope, but then again pretty much everything about Bigger Than Life seems strange. James Mason stars as Ed Avery, a suburban school teacher trying to keep up a facade of domestic cheeriness until he’s stricken with a painful and deadly vascular disease. Faced with only months to live, Ed begins a new experimental hormone treatment at his doctors’ behest and finds himself miraculously cured with a new lease on life. Something’s off about this new Ed, though, and his family and friends (including Walter Matthau in an early role as Ed’s best friend, Wally the gym teacher) start to worry when his behavior grows more aggressive and erratic with each fistful of medication he gobbles. In other hands, a film about a father driven to infanticide by the stuff you put on mosquito bites could seem laughable, but Ray manages to conjure an aura of madness and bone-deep dread around even the scenario’s silliest bits of melodrama, evocatively using the extra screen space afforded by CinemaScope to film the Averys’ cavernous, dimly lit suburban home as if it were a tomb and Ed the ghoul haunting it. (CW)

95 min • 20th Century-Fox • 35mm from Criterion Pictures USA

Preceded by: “Fabulous Las Vegas” (James B. Clark,1954) – 35mm

Thursday, April 7 @ 7:00 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

In Spring

Directed by Mikhail Kaufman • 1929

The documentary collective of director Dziga Vertov, his wife and editor Yelizaveta Svilova, and his brother and cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman produced some of the most innovative experiments of Ukrainian silent cinema, culminating in The Man With a Movie Camera (1929). An acrimonious split during the postproduction of that film left Kaufman charting his own path, and the result was In Spring, a monumental fresco of life in Kyiv keyed to the changing of the seasons. (The self-reflexive aspects of The Man With a Movie Camera are almost entirely suppressed, though Kaufman delivers a parade of kolkhoz kittens and puppies that more than make up for their loss.) Devoid of intertitles, In Spring literally examines life from the ground up, spiraling out from the soil itself to the modern machines used to cultivate it and the society it sustains. For the film historian Georges Sadoul, the film “made us discover a completely new form of documentary cinema, a cine-poem, where the lyrical theme of thaw and swelling buds conveyed the pathos of the advancement of the USSR towards building socialism without concealing the still existing remnants of the past.” As in the best Soviet-era films, the clamor and color of daily life are marshalled to illustrate Stalinist ideology, but they also transcend its confines, leaving a fecund portrait of a vanished society. (KW)

60 min • Vufku • 35mm from Yale Film Archive

Live piano accompaniment by Dave Drazin!

CFS originally planned to show this film in April 2020.

Saturday, April 16 @ 11:30 AM / Music Box Theatre

THE FIRE BRIGADE

Directed by William Nigh • 1926

Are you a soldier in the Army of Peace or a weasel-faced chair-warmer? That’s the central question posed by The Fire Brigade, M-G-M’s extra-patriotic ode to civilian firefighters, which the studio sold as a spiritual follow-up to its World War I epic, The Big Parade. Three generations of Irish American men in uniform serve their country in a sleepy firehouse on the edge of town, where the aged Pop O’Neil (Bert Woodruff) dreams of showing up the new-fangled motorized engines with his loyal trio of veteran horses. His grandson, Terry (Charles Ray), still has a lot to learn about the family trade—if only he can keep his eyes on the prize of selfless sacrifice, which becomes much harder after he meets Helen (May McAvoy), the daughter of a prominent local builder and philanthropist. An action movie with an unusual social conscience, The Fire Brigade alternates relentless stunts with fiery denunciations of municipal graft. This five-alarm spectacle is further enlivened by a pair of recently restored color sequences: a flash of two-color Technicolor and a climactic use of the Handschiegl process that illuminates the flames of a burning orphanage. Preserved by The Library of Congress and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. (KW)

94 min • Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer • 35mm from Library of Congress

Preceded by: Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in “Fiery Firemen” (Rudoph Ising & Friz Freleng, 1928) – 7 min – 16mm

Live musical accompaniment by Music Box house organist Dennis Scott

Wednesday, April 20 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

THE BALLAD OF CABLE HOGUE

Directed by Sam Peckinpah • 1970

Sam Peckinpah got his start in Hollywood making Westerns, and during his early years there they were basically all he made. The brutally unsentimental view of frontier life and the directorial predilection for graphic bloodshed he developed during that time reached their apotheosis in his international breakthrough The Wild Bunch. The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Peckinpah’s follow-up to his controversial hit, may have been yet another cowboy picture, but it was also the rare entry in his filmography you could actually call “pleasant,” a hard turn away from the antisocial violence his career would become synonymous with and towards warm and winningly cornpone comedy. Jason Robards stars as the title character, an entrepreneurial frontiersman who stumbles across a conveniently located desert watering hole and decides to set up shop. Occasionally assisted by area sex pest Reverend Joshua (David Warner) and Hildy (Stella Stevens), the prostitute he’s fallen in love with, Hogue affably makes his fortune there on the road between Gila and Dead Dog, selling water usage rights to the stagecoach companies and rattlesnake stew to tourists. Mostly dispensing with things like “conflict” and “plot,” The Ballad of Cable Hogue chooses to simply bask in the beauty of its Technicolor vistas and the good humor of its cast (a murderers’ row of Western character actors including Slim Pickens, Strother Martin, L.Q. Jones, and Peter Whitney), ambling along with Cable, Hildy, and co. as they pratfall down stairs and sing sweet little cowboy songs to each other. Screening in an original technicolor print! (CW)

121 min • Warner Bros. • 35mm IB Technicolor from Chicago Film Society collections, permission WB/Swank

Preceded by: “Fin ‘n Catty” (Chuck Jones, 1943) – 7 min – 16mm

Wednesday, April 27 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

THE MARRYING KIND

Directed by George Cukor • 1952

After director George Cukor, writer Garson Kanin, and actress Judy Holliday spun a popular, Oscar-winning comedy out of Broadway’s Born Yesterday, they asserted their prerogative to make a very different kind of picture for their follow-up. The Marrying Kind, an original idea from Kanin and his wife and writing partner Ruth Gordon, begins in judge’s chambers at New York Court of Domestic Relations and recounts the backstory behind an imminent divorce. Working stiffs Florence (Holliday) and Chet Keefer (Aldo Ray, in his first starring role) meet in Central Park and soon embark on a whirlwind courtship, culminating in an Atlantic City honeymoon and a new start in New York’s smallest, crummiest tenement apartment. The Marrying Kind follows the Keefers’ conjugal ups and downs, from minor misunderstandings to stark tragedies. (Luckily, the tone is enlivened by periodic trips to Chet’s workplace, the United States Postal Service, here depicted correctly as the jolliest civic institution.) When Kanin pitched Cukor on the project, he described something high-minded and new: “Its aim is realism. Its tone is documentary rather than arty, its medium is photography rather than caricature. I think it is the closest we have ever come to ‘holding the mirror up to nature.’” Alas, the studio didn’t know what to make of the sensitive finished product and fell back on ill-suited clichés to promote it, with a poster showing Holliday socking Ray and counseling him to “SHADDUP!” (KW)

93 min • Columbia Pictures • 35mm from Sony Pictures Repertory

Preceded by: “Life with Baby” (March of Time, 1946) – 19 min – 16mm

Wednesday, May 4 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

CITY LIGHTS

Directed by Charles Chaplin • 1931

Four years after the talkies had begun to displace silent cinema—after talking ducks were all quacked out, after all-singing, all-dancing musicals had delighted and then repulsed audiences, after new stars had eclipsed old—Charles Chaplin emerged with a new silent melodrama. Though enlivened by Chaplin’s own musical score, some syncopated gibberish, and a handful of sound effects, City Lights was very much a throwback, a perfectionist’s unhurried testament, scarcely bothered or even aware of fashion or favor. As Dave Kehr has observed, Chaplin’s features “would wander all over the place, lingering here and lingering there—but more often than not he got something better than traditional dramatic unity.” So it is with the narratively loose but thematically tight City Lights, which chronicles the Little Tramp’s precarious friendships with two people who cannot or will not recognize him: a blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill) who’s never seen his face and an inebriated millionaire (Harry Myers) who can’t remember his face in sobriety’s haze. The disappointments, frustrations, and joys of all human relationships can be glimpsed in this clumsy triangle. Incidentally, it’s also a comedy, and with some of Chaplin’s best bits: a party gone wrong, a boxing match gone right, and a whistle gone missing. (KW)

87 min • United Artists • 35mm from Janus

Preceded by: “Light Isle” (Matthew Hidy, 2019) – 4 min – 16mm

Programmed and Projected by Julian Antos, Becca Hall, Rebecca Lyon, Tavi Veraldi, Kyle Westphal, and Cameron Worden.

Research Associate: Mike Quintero

Heartfelt Thanks to

Shayne Pepper, Cyndi Moran, Robert Ritsema, Ernie Kimlin, Chris Rodriguez, & Jose Aguinaga of Northeastern Illinois University; Brian Andreotti & Ryan Oestreich of the Music Box Theatre; Brian Belovarac of Janus Films; James Bond of Full Aperture Systems; Dennis Chong, Jesse Chow, Liam Berney, Jason Jackowski, & Eric Chin of Universal; Chris Chouinard of Park Circus; Amy Crismer of Disney; Justin Dennis of Kinora; Olivia Babler, Yasmin Desouki, & Nancy Watrous of Chicago Film Archives; Jesse Hawthorne Ficks; Cary Haber of Criterion Pictures, USA; Dave Jennings of Sony Pictures Repertory; Thad Komorowski; Steven Lloyd; Divi Logan; Seth Mitter of Canyon Cinema; Kristie Nakamura & Nicole Woods of Warner Bros. Classics; Dennis Scott; Lynanne Schweighofer, Rob Stone, & Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress; Tommy José Stathes; Katie Trainor & James Layton of the Museum of Modern Art; Jaclyn Wu of Harold Lloyd Entertainment. Particular thanks to CFS research associate Mike Quintero, CFS board members Mimi Brody, Steven Lucy, Brigid Maniates, & Artemis Willis, & CFS advisory board members Brian Block, Lori Felker, & Andy Uhrich.

And extra special thanks to our audience, who make it all possible!