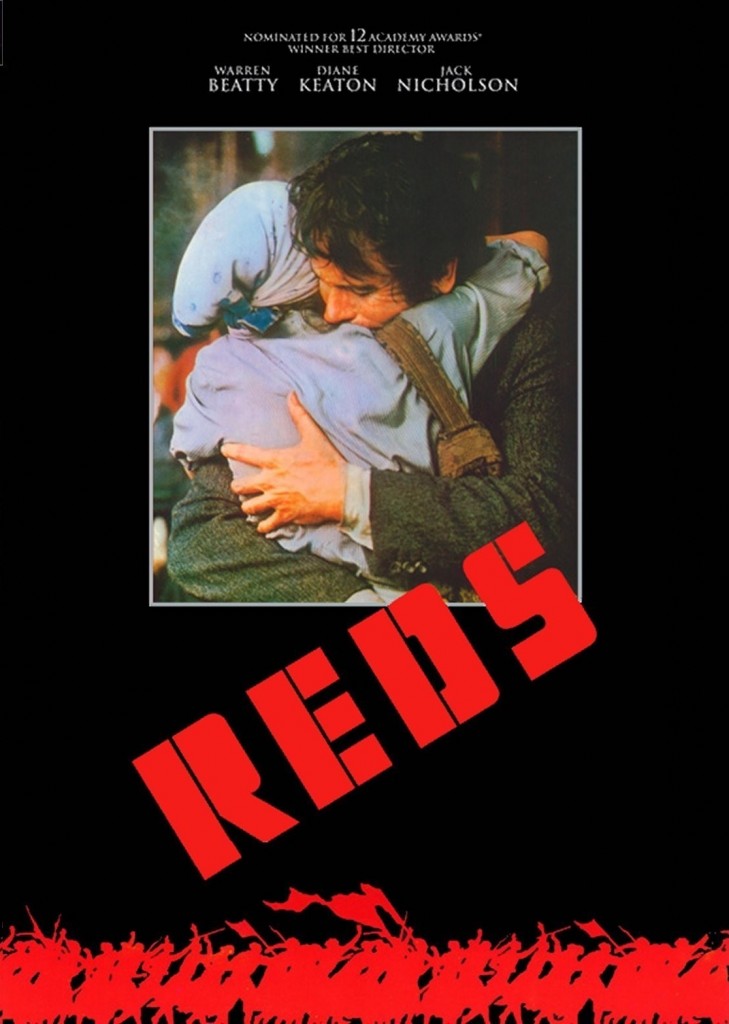

When Reds was released in late 1981, its admirers tended to downplay its political dimension. It was a sweeping romance that happened to be about Communists—a perhaps necessary bluff (or a revealing delusion) after American politics had taken a sharp swing towards the right. “It is that personal, human John Reed that Warren Beatty’s ‘Reds’ takes as its subject,” Roger Ebert assured us, but not without cautioning that “there is a lot, and maybe too much, of the political John Reed as well.” Andrew Sarris, who had frequently used his Village Voice perch to mock routinely liberal movies, finally found one he could get behind. “Reds is more a love story than a revolutionary chronicle,” Sarris wrote, “and as it happens, I prefer love stories to revolutionary chronicles.”

When Reds was released in late 1981, its admirers tended to downplay its political dimension. It was a sweeping romance that happened to be about Communists—a perhaps necessary bluff (or a revealing delusion) after American politics had taken a sharp swing towards the right. “It is that personal, human John Reed that Warren Beatty’s ‘Reds’ takes as its subject,” Roger Ebert assured us, but not without cautioning that “there is a lot, and maybe too much, of the political John Reed as well.” Andrew Sarris, who had frequently used his Village Voice perch to mock routinely liberal movies, finally found one he could get behind. “Reds is more a love story than a revolutionary chronicle,” Sarris wrote, “and as it happens, I prefer love stories to revolutionary chronicles.”

The detractors tended to agree with the brunt of this assessment, but understandably saw this as a liability. Pauline Kael called it “the least radical, the least innovative epic you can imagine” and the Soho News corrected the record with “What Reds Won’t Tell You About Louise Bryant.” It was a movie about John Reed that even Reagan could love—and indeed, he did. One can easily imagine him nodding along with Beatty’s Reed as he denounces Zinoviev for his individual-annihilating, freedom-denying brand of Communism.

Paramount’s 2006 small-scale reissue of Reds clearly addressed a shift in the political landscape. The trailer for the DVD positioned Reds as a blockbuster rendition of a prototypical Daily Kos diary, fired up with indignation over an illegal war and a dissent-crushing mainstream. Implicitly, Reds inaugurated a tradition that now included such softly provocative left-wing cinema-events as The Constant Gardener and Syriana.

Do we yet have the tools and sobriety to reckon with Reds? Its technical achievement is unimpeachable. There’s a moment early on in Reds when Bryant buttonholes Reed for an interview after his very brief speech at Portland’s Liberal Club. When can we talk? “Now,” and editors Dede Allen and Craig McKay cut on that word, that syllable to a scene in her apartment. The whole movie has this clipped quality, all tumbling out and jammed up together in a rush of decisions and judgments. In a sense, Reds feels like the culmination of the Resnais-influenced, half-glance New Hollywood editing style that Allen herself initiated in Bonnie and Clyde. Reds is the movie that fashions a working and supple grammar out of it. Nothing carries the appearance of classical cross-cutting here, even when that description is perfectly apt—the shots seem to hover, always looking stitched together and brittle, as if the whole edifice will atrophy when the music stops.