Guest post by Alexander Bohan

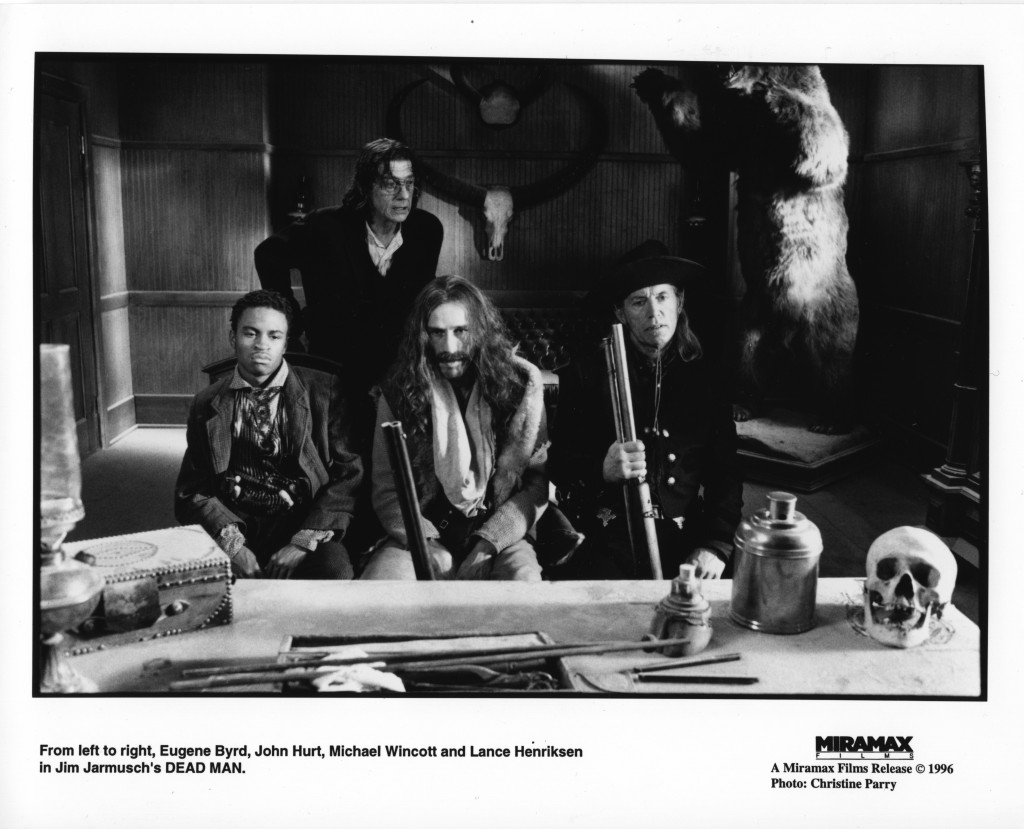

Thanks to Chicago filmmaker, projectionist, film historian and NW Chicago Film Society volunteer Alexander Bohan for sharing these scans of Lance Henriksen’s copy of the Dead Man script (click on the thumbnails to enlarge), and for sharing his experience getting to know Henriksen through his films and in person.

As an adolescent I became engrossed with the travels of Captain James T. Kirk and the Enterprise, the novels of Verne and Welles, and the absolute wonder of cinema that is 2001: a Space Odyssey. But as I grew older I began to see how my beloved films were used to convey the larger questions of life, namely, what does it mean to be human?

Lance Henriksen has devoted his life and his craft to answering this question. Henriksen is perhaps best known as the sympathetic android Bishop in James Cameron’s cinematic comic book – Aliens. Bishop exuded a boyish-like curiosity paired with an unexpected air of innocence and inexperience while being very intelligent and observant; like me, he too was naturally curious and yet socially guarded.

I began to seek out more films featuring Lance Henriksen. Among the most compelling discoveries was Kathryn Bigelow’s solo debut Near Dark. Near Dark offered a refreshingly original take on the vampire myth setting its drama against the gorgeous expanses of the American West. Henriksen immersed himself in a process he refers to as “gathering”; a creative phase best defined in his new autobiography as “a period of accumulating objects and details that he can draw on during the filming to flesh out his character” (Henriksen & Maddrey 86). This preparation coupled with the development of an elaborate back story serve as a kind of creative stimuli that encourages him to respond to a variety of situations on an instinctual level, offering him the fundamental cornerstones on which to build his multifaceted characters. After discovering the core of his character through writing, Henriksen begins his journey to work out the physical details. A true adherent to the Method’s emphasis on the body as an instrument, Lance dropped 140 pounds to become the walking corpse Jesse Hooker in Near Dark.

This process of total immersion into his characters often makes it difficult for Henriksen to “step out” of his roles during off time. Jim Jarmusch recalls the actor’s dedication to the role of Cole Wilson during the shooting of his film Dead Man as a slightly unnerving, but rewarding experience: “He stayed in character a lot of the time, which was a little scary. Some actors can just walk off the set and become themselves again, but Lance puts so much of himself into a performance that it takes him a little while [to get out of character].” (Henriksen & Maddrey 142)

Released in the spring of 1995, Dead Man offered another twist on a familiar genre. Dubbed as an “acid western” by its director, the film has more in common with Alejandro Jodorosky’s El Topo than the more classic depictions of the west rendered by Ford and Hawks. In those films the cowboy travels out of the wilderness and into town to restore order and maintain civilization. After addressing the evil and/or corruption threatening the community, the hero is called back into the wilderness where he remains until that day society becomes threatened once more.

The romanticism of the western myth grounded in the belief of manifest destiny that often pits the European pioneer against the Native American is at the heart of most of these narratives. Civilization is viewed strictly in terms of the preservation and celebration of Anglo traditions, lifestyle, and culture. Jarmusch’s Dead Man critiques this myth through the exploration and alteration of conventions that typify the genre. William Blake (Johnny Depp) starts the film as an accountant obeying Horace’s Greely’s decree to “go West, young man.” Through pure fortuity he comes into conflict with the very values he once symbolized and held dear and is labeled an outlaw. After becoming wounded, Blake “awakens,” in both a physical and spiritual sense, to assume the identity of the poet William Blake. Pursued by three legendary frontier killers, Blake embarks on a vision quest to return to the spirit world. His journey towards death is symbolized through his parallel journey to go deeper into the West. This subversion of the Western myth equates expansion with death, something which is further symbolized in Blake’s transformation from a meek accountant into a renegade poet making peace with his life. Acid western in both look and feel, Dead Man’s trip, visually and narratively (i.e. Blake’s journey), marks the film as one of the more startling pieces of existentialist cinema to emerge from the 1990s.

While every last detail is period accurate something remains amiss. The inhabitants of the town of Machine look and act like the pioneers of yesteryear and yet their actions and the world they inhabit seem slightly askew; they are, like the town’s name, mechanistic. This strange sense of irony seemed perfectly suited for an actor who much like his director didn’t like to play by the rules.

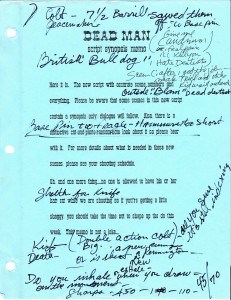

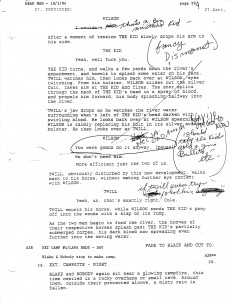

During their first meeting, Henriksen shocked Jarmusch with his radical approach to an already off-kilter film. Lance stated he would not recite any line of dialogue written for his character in the script. Jarmusch entertained the actor’s proposal and inquired further as to how this would be accomplished. Henriksen replied, “You’ll see when we get into the situations” (Henriksen & Maddrey 205). Jarmusch embraced Henriksen’s offbeat approach as a gift resulting in a creative collaboration between actor and director: “I write my own films, so I’ve invented the characters in my head, but someone like Lance is going to elevate the character above what I could imagine alone…and hopefully I’m going to elevate it above what he would imagine on his own.” (Henriksen & Maddrey 142)

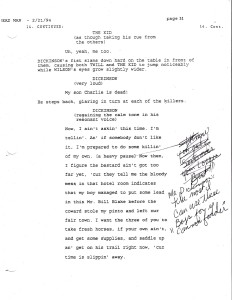

Lance’s portrayal of the ruthless killer is one of the most disturbing performances captured in a Western. We’re told that his character “fucked his parents,” “killed them,” “cooked them and ate them,” presumably in that order. Barely uttering a word, Cole travels the countryside with relentless determination to find and kill William Blake. Henriksen saw his character as an “ecological disaster.” Cole was an uncontrollable and unpredictable force to be reckoned with. One can never be too sure if he is being playful or simply delighting in his demented desires.

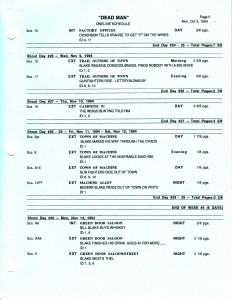

Just as intriguing as Cole’s unpredictability was the uncertainty surrounding who to credit for certain contributions to the creation of his character. What elements were Jarmusch’s and what were Henriksen’s? As a fan of the actor and his work, these questions intrigued me. The opportunity for answers came when the actor placed his original script up for a charity auction. After securing the document, I began sifting through the marked up pages of Jarmusch’s modern classic. I couldn’t believe my good fortune! In my hands I held an autographed script filled to the brim with character notes and ideas Lance had during the shooting process. These fascinating anecdotes were further complemented with the inclusion of a shooting schedule specifically prepared for Lance’s character, also known as a “oneline schedule,” and a memo sent from Jarmusch to the cast and crew prior to the first week of production. These artifacts not only evidenced Lance’s creative “gathering” process,” but also proved the unique collaboration of actor and director on and off set.

The plethora of information and insight was incredible, but I remain puzzled over a ballpoint note scrawled on the back of page 58 which read:

Twill – he was just a kid –

Me – He’s a Navajo Mud Toy now –

What on earth did he mean by “Navajo Mud Toy”? There was no mention of this strange reference anywhere in the script. Could this have been a line that Lance insisted on, but which never made it into Jarmusch’s final cut? The chance for an answer came when an annual horror convention announced a cast reunion for Near Dark with Lance Henriksen in attendance.

Over many decades Lance had amassed a large and dedicated fan base. Many only knew the actor from perennial favorites such as Aliens and Near Dark. Standing in line with script in hand I waited and watched as several fans took pictures and collected signed photos. I didn’t need any signed photographs as I had two signed glossy stills, two autographed scripts that had belonged to the actor, and two film prints stored in an archive one of which was on its way to festival in Spain. Through a strange turn of events, I had become an unauthorized expert on the actor and his films. The time had almost come for me to ask my question. I had met Lance once before at a similar event where my father and I asked him about his work with director Sidney Lumet. The man remained a fascinating font of information about the business and the filmmaking process from an actor’s point of view. He was an absolute joy to talk to and one of the most down-to-earth, personable actors ever.

The actor paused as I approached him, his eyes fixed on the tattered script I held in my hand. “Where did you find that?” he said with a smile and wide eyed stare. After a brief reintroduction, I opened the document to the page I remained most puzzled about. “What did you mean by Navajo Mud Toy,” I asked. His hands gently took the script from mine. He smiled. My dad and I stood transfixed as the actor regaled us with his story about the origins of the mysterious note, which was written in reference to a scene where Cole dispatches one of his accomplices in cold blood.

In the film, Cole Wilson travels throughout the countryside with two nefarious men hired by an industrialist (Robert Mitchum) to find and kill William Blake, who he believes murdered his son. These less than desirable sidekicks banter back and forth while Cole Wilson remains stoic and focused on the task at hand. Eventually their jabbering gets to him. In a scene devoid of any passion, Cole turns to his prattling companions and points his gun at the youngest – “The Kid” played by Eugene Bird. The violence is brief and incredibly matter of fact; no emotion whatsoever. Henriksen explained how he discovered finding that empty shell of man during production.

During a visit to Flagstaff, Arizona he stopped by a local trading post. He found a small object; a clay brick with a car painted on it nestled beside a variety of knickknacks the store owner was peddling. Standing their motionless with wonder, Lance asked the store owner what it was. “A Navajo Mud Toy,” he replied. Henrkisen later drew from that experience for the scene where he dispatches The Kid. The fragile, handmade object resonated with him in an emotional way. For the unfeeling Cole, his unwanted companion had the same value to him as that cheap, disposable trinket; he was no more than a Navajo Mud Toy.

Lance closed the script and handed it back to me and shook our hands. “Thank you,” he said with a smile filled with warmth and generosity. It’s a moment I’ll never forget and one that I cherish as I continue my film studies. Dead Man is a film of startling beauty built on the genius of Jarmusch and brought to life by a dedicated cast who believe in their craft.

For more on Lance Henriksen: “Not Bad for a Human: The Life and Films of Lance Henriksen.”

Henriksen, Lance, and Joseph Maddrey. Alexander Henriksen Press, in conjunction with Bloody Pulp Books. Copyright 2011.