We’re not supposed to judge a book by its cover, but can we draw any conclusions about a movie from its running time alone? More than just numerical data, a film’s running time often offers substantive clues to its presumed audience, production circumstances, and formal strategies. Speaking personally, I tend to be suspicious of any film longer than 75 minutes, unless it has the reckless chutzpah to exceed 160.

We’re not supposed to judge a book by its cover, but can we draw any conclusions about a movie from its running time alone? More than just numerical data, a film’s running time often offers substantive clues to its presumed audience, production circumstances, and formal strategies. Speaking personally, I tend to be suspicious of any film longer than 75 minutes, unless it has the reckless chutzpah to exceed 160.

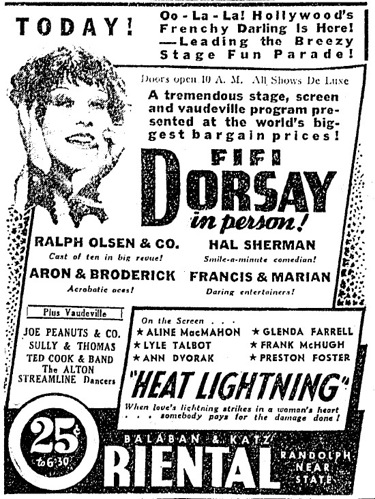

Our Wednesday feature, Heat Lightning, illustrates this doctrine perfectly. It lasts a scant 63 minutes, and boasts richer atmospherics and more finely-drawn major characters than many movies twice its length. Heat Lightning is economical in its construction, but also terse, blunt, and sketchy in its poetics. (And another bonus: for a programmer’s balance sheet, the fleetness of a short feature like Heat Lightning also translates into substantially reduced shipping costs—one clunky 35mm Goldberg shipping canister rather than two.)

In some sense, the qualities of Heat Lightning derive from its admittedly assembly-line blueprint and protracted exhibition fate. Heat Lightning was produced at a time when anxious theaters were plying moviegoers with a newsreel, a cartoon, a comedy short, a travelogue, a double feature, and occasionally dinnerware enticements for one low, low admission price. The makers of these movies assumed that nobody was going to look at their wares too long or too critically. No loitering here; within a week, Heat Lightning would be shipped off to another theater in another city and something else would take its place.

The best Hollywood filmmaking of the thirties was generally short and zippy, but also assumed some a level of built-in audience recognition. If all the grifters and showgirls and strivers were essentially interchangeable, so much the better: any seasoned moviegoer could walk into a theater at any point and instantly understand all the character dynamics and motivations. The situations functioned like dramatic pictograms. Watch enough of these movies, and you’ll find yourself wondering why any movie needs to be two hours long.

The best Hollywood filmmaking of the thirties was generally short and zippy, but also assumed some a level of built-in audience recognition. If all the grifters and showgirls and strivers were essentially interchangeable, so much the better: any seasoned moviegoer could walk into a theater at any point and instantly understand all the character dynamics and motivations. The situations functioned like dramatic pictograms. Watch enough of these movies, and you’ll find yourself wondering why any movie needs to be two hours long.

In a larger sense, a movie’s running time often indicates who made it, but also which side it’s on. With a few suitably scrappy exceptions like Five Star Final and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, the Warner Bros. pictures of the early thirties don’t bother with posterity. They’re movies made by people punching a clock (and, just as significant, probably not earning time and a half for it). One movie shoot ends and the next one begins; in this way, Warner workhorse directors like Michael Curtiz, William Wellman, Roy Del Ruth, Lloyd Bacon, Archie Mayo, and Mervyn LeRoy wound up signing five, six, seven films a year.

It’s not until the considerably longer and more expensive ventures like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Anthony Adverse, and The Life of Emile Zola that the studio garnered real critical and industry recognition. (It’s no accident that Warner Bros. was the last of the major studios to earn an Academy Award for Best Picture; by the time Zola won the big prize in 1937, M-G-M had already received that citation three times)

We still take running time as shorthand for a movie’s position—proletariat, middle-brow, or otherwise. If a movie runs 136 minutes, it’s probably an Oscar bait literary adaptation. If it’s 98 minutes, or perhaps 103, it’s probably an anonymous thriller pitched to divorced dads. Any movie under 80 minutes, it’s kid’s stuff. That Norman M. Klein should title his brilliant study of theatrical cartoons Seven Minutes is instructive.

These predictive measurements aren’t necessarily cynical. When P.T. Anderson vowed that his follow-up to Magnolia would be a 90-minute Adam Sandler movie, he was being both precise and sincere. The resultant masterpiece, Punch-Drunk Love, vindicated and transcended the label: an avant-garde scrambling of Sandler’s man-child tropes from Billy Madison and Happy Gilmore, raised to the level of clinical psychosis. (Like the movies of the thirties, Punch-Drunk Love is a work of art enriched by familiarity with its disreputable brethren.)

If short movies ingratiate with their guttural, unpretentious aspirations, the very long film invites deluxe identification. Whether they court novelistic density (Doomed Love), epic patience (Lawrence of Arabia), unwieldy communal and spiritual scope (Sátántangó or The Chelsea Girls), the very long film summons a unique kind of concentration. They also summon a productive kind of incredulousness: we might ignore a two-hour version of Hatari!, but what on Earth possessed anyone to make a nearly three-hour rendition of the same material? A must-see, in other words.

If short movies ingratiate with their guttural, unpretentious aspirations, the very long film invites deluxe identification. Whether they court novelistic density (Doomed Love), epic patience (Lawrence of Arabia), unwieldy communal and spiritual scope (Sátántangó or The Chelsea Girls), the very long film summons a unique kind of concentration. They also summon a productive kind of incredulousness: we might ignore a two-hour version of Hatari!, but what on Earth possessed anyone to make a nearly three-hour rendition of the same material? A must-see, in other words.

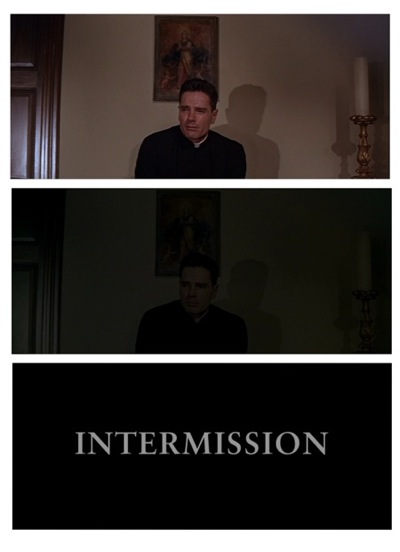

Though we still get very long films now and then (Titanic, Carlos, The Return of the King, Gods and Generals, Mysteries of Lisbon), we’re rarely granted the form’s secret weapon: the intermission.

The intermission was inherited from the legitimate stage and rarely used with any formal precision during the silent era. It was a mark of self-appointed respectability and largesse, not any practical concession to the audience’s patience. (The 1925 version of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, the most grandiose production of the silent period, had two intermissions.) Its use seems to have dropped off with the early talkies, which were, after all, comparatively short. Intermissions returned now and then for very prestigious productions, like Disney’s two-hour Fantasia.

It’s not until the widescreen era and its road show exhibition model that the intermission matured into an aesthetic device. Though often serving as a simple dramatic underline, the best intermissions achieved something more. The fade-outs in The Cardinal or 2001: A Space Odyssey project a throbbing emotional instability that no straight cut could convey. They’re moments of intangible promise and threat that the narrative trajectory cannot normalize. We must leave the auditorium and acclimate to being unstuck in time. The intermission may last ten or fifteen minutes, but the rupture is indeterminate. When we return, we will accept anything—a leap of years or a total shuffling of allegiances.

It’s not until the widescreen era and its road show exhibition model that the intermission matured into an aesthetic device. Though often serving as a simple dramatic underline, the best intermissions achieved something more. The fade-outs in The Cardinal or 2001: A Space Odyssey project a throbbing emotional instability that no straight cut could convey. They’re moments of intangible promise and threat that the narrative trajectory cannot normalize. We must leave the auditorium and acclimate to being unstuck in time. The intermission may last ten or fifteen minutes, but the rupture is indeterminate. When we return, we will accept anything—a leap of years or a total shuffling of allegiances.

In their heyday, intermissions retained their measure of prestige, too. But it was an ephemeral prestige. When films moved from their exclusive initial downtown runs to neighborhood engagements, the intermission (and overture and exit music) would often be dropped, shoehorning delicate temporal experiments into standard packaging. The worst fate was that of the presumptive epic planned with an intermission but dispatched to the world without one when the studio lost faith. The King Vidor-Dino de Laurentiis VistaVision superproduction of War and Peace was one of the most expensive efforts of the fifties, but it was unhelpfully shown straight through at 208 minutes in its premiere run, as if the studio was simply trying to cut its losses and shuffle past.

Many contemporary epics would unquestionably benefit from the addition of an intermission (Gangs of New York in particular), but it’s a luxury that modern exhibition cannot abide. Without reserved seats and premium pricing, theater owners have little reason to voluntarily run fewer showings per day. Multiplexes run from dusk to dawn, with varying degrees of automation. Even if audiences had these intervals again, would they know how to process them? Comically, when the Weinstein Company opted to release the Rodriguez-Tarantino Grindhouse with a nominal intermission, theaters reported that many ticket-buyers left after the first half unaware that they were entitled to a second.

Suggestively, intermissions achieve their most radical formal and narrative effect by taking us away from the screen and reminding us of a parallel system of time. Discussing epic running time and intermission restores the centrality of one underrated aspect of movie-going: duration. Plainly, movies make demands on our time. (It’s commonplace to hear that a movie was a waste of time; only the aesthetes complain that it was a waste of eyesight.) How we choose to assimilate that time gets to the root of what movies do. Fred Camper has described this aspect eloquently in his review of Shoah:

In Shoah the endless recounting of detail introduces an ineffable sadness. But as the film progresses, its length gains another significance: the viewer begins to feel the way in which the film is taking a large chunk of time out of his day, out of his life. The standard two-hour feature format is something to which we are all accustomed, and a two-hour film tends to enclose or encapsulate itself as an object, its duration a thing we are used to accepting as part of the rhythm of daily living. But a very long film, even one of only four or five hours … carves a significant space out of one’s temporal field. We attend to it differently; it intrudes more directly into our thoughts and lives, an intrusion thoroughly appropriate to Shoah’s subject.

Some of the most exciting movies, whether long or short, call attention to the fact that cinema, rather than being escapist, actually has something to do with our lives: the long bedroom scene in Godard’s Breathless, the meteorological procession of Gottheim’s Fog Line, the escalating tension of Linklater’s Before Sunset, the soporific rhythms of Warhol’s five-hour Sleep, the endless bareback ride of King’s Chad Hanna, the languorous jungle sequence that makes up the latter half of Apichatpong’s Tropical Malady. More than simply taking place “in real time,” these movies invest the movements of everyday life with form, dignity, and scale. In watching them on screen, we become engaged again with our own time.