The Director as Commodity

I couldn’t help chuckling over a poster glimpsed in the Cinemark lobby recently—an advertisement that boasted that only RealD’s 3D system allowed the audience to see the movie exactly “as the director intended.”

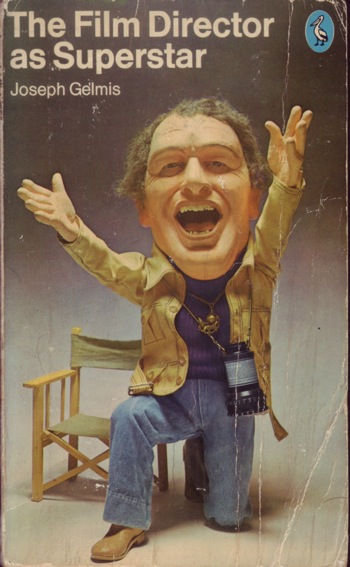

You probably don’t need a stereoscopic slogan to recognize that director is routinely and reflexively held up as a film’s author, its artist, and its true voice. Between director’s commentaries and director’s cuts, the fledging auteurism of the ’60s has become commodified and thoroughly unremarkable. Indeed, we’re so inured to the director cult that we often neglect to examine some of the critical assumptions that underpin auteurism.

The official story behind the auteurist upheavals goes something like this: for decades, film was not taken seriously as an art form. When it was taken seriously, the wrong movies were celebrated because the wrong artists were singled out: producers, movie stars, screenwriters, and front office hacks. Critics dismissed all kinds of wonderful films because their silly stories and outrageous appeals did not conform to pretentious literary standards. It took Andrew Sarris and his young acolytes to steer the critical ship elsewhere, towards recognition of the director as the most important contributor to a film—its auteur. Sarris’s articles in Film Culture and his subsequent book The American Cinema taught a legion of young cinephiles to ditch the dialogue and focus on the mise-en-scene. Some old-fashioned critics, like Pauline Kael, resisted the auteurist fervor and became irrelevant fossils. (We’re telling this story from the auteurist’s perspective, remember, so disregard Kael’s enduring popularity and reputation, including last year’s Library of America compendium of her criticism.)

The official story behind the auteurist upheavals goes something like this: for decades, film was not taken seriously as an art form. When it was taken seriously, the wrong movies were celebrated because the wrong artists were singled out: producers, movie stars, screenwriters, and front office hacks. Critics dismissed all kinds of wonderful films because their silly stories and outrageous appeals did not conform to pretentious literary standards. It took Andrew Sarris and his young acolytes to steer the critical ship elsewhere, towards recognition of the director as the most important contributor to a film—its auteur. Sarris’s articles in Film Culture and his subsequent book The American Cinema taught a legion of young cinephiles to ditch the dialogue and focus on the mise-en-scene. Some old-fashioned critics, like Pauline Kael, resisted the auteurist fervor and became irrelevant fossils. (We’re telling this story from the auteurist’s perspective, remember, so disregard Kael’s enduring popularity and reputation, including last year’s Library of America compendium of her criticism.)

The standard version glosses over some important things. Directors were hardly invisible in the days before Sarris, and film histories published before An American Cinema certainly treated figures like Chaplin, Eisenstein, Lang, Hitchcock, and Capra as artists. More importantly, much as the auteurists frequently lambasted literary tendencies among their colleagues, their own criticism tended to treat films as texts—charting a director’s pet subjects and symbols between works, emphasizing thematic continuity over the course of a career. Rather than outlining a new kind of criticism, they adapted the insular close reading of New Criticism to film.

This literary approach to film criticism has persisted since the 1960s. Talking about a director means treating individual films as isolated systems; they interact with other titles in the director’s oeuvre, but rarely with the wider world. Biography becomes trivia, an irrelevant attempt to venture outside the film itself. In this formulation, the director’s political orientation and private causes occupy a place only slightly above tabloid sex gossip.

An Alternative Approach: Irving Lerner

What would happen if we treated the director differently?

The highly varied career of Irving Lerner provides a fascinating counterpoint to conventional auteurism. Looking for thematic or visual continuity is a fool’s errand—there’s no singular “Lerner style” linking his work across the decades. Compounding the problem is the fact that Lerner often worked under pseudonyms or did not receive credit for his work at all. To even describe Lerner as a director perhaps unnecessarily privileges his relatively few directorial credits at the expense of the other productions for which he performed odd jobs. (Indeed, his longtime collaborator Ben Maddow, who contributed to the script of Murder by Contract without credit, described Lerner as “a very wonderful editor but a terrible director. He just didn’t know where to put the camera.”)

The highly varied career of Irving Lerner provides a fascinating counterpoint to conventional auteurism. Looking for thematic or visual continuity is a fool’s errand—there’s no singular “Lerner style” linking his work across the decades. Compounding the problem is the fact that Lerner often worked under pseudonyms or did not receive credit for his work at all. To even describe Lerner as a director perhaps unnecessarily privileges his relatively few directorial credits at the expense of the other productions for which he performed odd jobs. (Indeed, his longtime collaborator Ben Maddow, who contributed to the script of Murder by Contract without credit, described Lerner as “a very wonderful editor but a terrible director. He just didn’t know where to put the camera.”)

The knotty shape of Lerner’s career is not a barrier to understanding; instead, the twists and turns exemplify the challenges and compromises faced by a generation of left-wing artists working in the film industry—sometimes in major productions, but more often at the margins. In some ways, Lerner’s case is emblematic. He appears, Zelig-like, at crucial moments in the development of non-Hollywood filmmaking.

Beginning as a member of the Worker’s Film & Photo League in his early twenties, Lerner cut his teeth on the League’s radical newsreels. Lerner never contributed to the League’s newsletter, Filmfront, but he did write criticism for New Theatre and New Masses. (In the latter, his articles appeared under the byline of Peter Ellis, a pseudonym that Lerner would reuse for some of his documentaries). His New Theatre pieces include a typically tendentious rejection of pioneering documentarian Robert Flaherty:

But nowhere did [Nanook of the North] show the social life of the Eskimo …. Even his Nanook was a Robinson Crusoe in furs. As far as the film was concerned Nanook and his family were the only Eskimos in Canada. And of course there was no class struggle, there was no exploitation, there was no oppression! It was too obvious; too banal for Robert Flaherty.

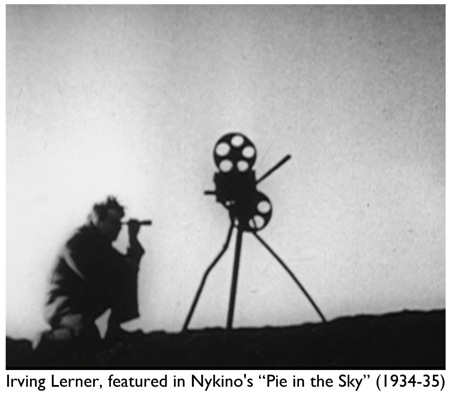

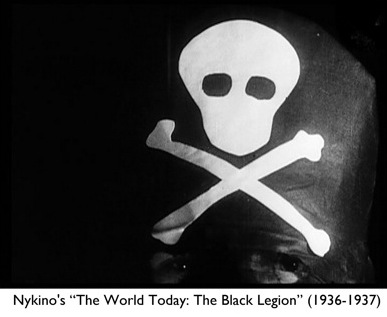

Lerner’s desire for a class-conscious documentary cinema hardly found better reception at the Film & Photo League. Though everyone affiliated with the FPL was a radical of some stripe, discord and factionalism ran rampant, as they often did on the left in the 1930s. Lerner split from FPL and founded Nykino with Ralph Steiner and Leo Hurwitz. The collective embarked on a series of films that would shed light on right-wing hypocrisies of the day, from religious cant to vigilantism. (One early production, Pie in the Sky, was based loosely on Joe Hill’s anthem and featured the young Group Theatre actor Elia “Gadget” Kazan.) Nykino eventually became Frontier Films, the group responsible (after Lerner’s departure) for Native Land, the feature-length apotheosis of ’30s radical cinema.

Lerner’s desire for a class-conscious documentary cinema hardly found better reception at the Film & Photo League. Though everyone affiliated with the FPL was a radical of some stripe, discord and factionalism ran rampant, as they often did on the left in the 1930s. Lerner split from FPL and founded Nykino with Ralph Steiner and Leo Hurwitz. The collective embarked on a series of films that would shed light on right-wing hypocrisies of the day, from religious cant to vigilantism. (One early production, Pie in the Sky, was based loosely on Joe Hill’s anthem and featured the young Group Theatre actor Elia “Gadget” Kazan.) Nykino eventually became Frontier Films, the group responsible (after Lerner’s departure) for Native Land, the feature-length apotheosis of ’30s radical cinema.

Work-for-Hire

Politically-engaged, independent filmmaking was, naturally, difficult to sustain in economically calamitous times. Many left-wing filmmakers—Lerner, Steiner, Willard van Dyke, Paul Strand—eventually wound their way to sponsored productions, taking commissions from city governments and trade associations. A Place to Live, Lerner’s project for the Philadelphia Housing Association, blends fiction and reportage to make a succinct case for urban renewal—a good liberal cause in its day, albeit one whose paternalistic, community-shattering consequences are now routinely (and correctly) decried by latter-day liberals. At least Lerner’s contribution to the urban renewal genre goes about its business in a resolutely color-blind way and looks forward to an integrated society. The same cannot be said for Steiner and van Dyke’s The City, the sensation of the 1939 World’s Fair, which contrasts black urban poverty with the lilly white promise of the suburbs.

As the New Deal gave way to Total War, Lerner found himself working, as many radicals did, for the US Government. On the strength of A Place to Live, he headed up film production for the Office of War Information’s Overseas Unit. He was charged, flatly, with producing government propaganda to sell America to the world. Unlike Capra’s celebrated Why We Fight series, Lerner’s films received no domestic theatrical distribution and thus had little chance of contributing to his critical reputation. Indeed, as made-to-order government propaganda, the films carry titles but no personnel credits—a serious barrier to sorting out who did what. Scholars have attributed the production and direction of The Autobiography of a Jeep to Lerner (it’s a cute film about the superiority of U.S. engineering, narrated by a Jeep), but it’s understandably difficult to establish a full filmography without access to archival sources.

If Lerner lacked a sense of big-time careerism, he nevertheless worked constantly. He knew his way around several different crafts, plying his trade as director, assistant director, editor, and cinematographer. He had an occasional personal project, such as Muscle Beach, which he co-directed with Joseph Strick. Amazingly, Muscle Beach manages to turn a disreputable gay cruising spot into an All-American family playground! Almost totally unknown today (and unnecessarily so, as the Academy Film Archive has done a beautiful job of preserving it), Muscle Beach was apparently the talk of the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1951. The British film journal Sequence reported:

If Lerner lacked a sense of big-time careerism, he nevertheless worked constantly. He knew his way around several different crafts, plying his trade as director, assistant director, editor, and cinematographer. He had an occasional personal project, such as Muscle Beach, which he co-directed with Joseph Strick. Amazingly, Muscle Beach manages to turn a disreputable gay cruising spot into an All-American family playground! Almost totally unknown today (and unnecessarily so, as the Academy Film Archive has done a beautiful job of preserving it), Muscle Beach was apparently the talk of the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1951. The British film journal Sequence reported:

In complete contrast to anything else the evening had disclosed was the already legendary Muscle Beach. Here the poet’s eye strays observantly, ruminatively, amusedly, over a crowded summer beach, where acrobats and weight-lifters are exercising, young people are lying out in the sun, and their children paddle and gape at the strange antics of their elders. So dazzling are the patterns and rhythms of its editing that one can easily miss the shapeliness of the structure of this perfect little film, whose easy transitions from the lyrical to the humorous are so happily enhanced by Earl Robinson’s guitar accompaniment and Edwin Rolfe’s witty and affectionate words.

Lerner’s path was, again, not unique—his choices parallel the changing currents of non-theatrical film. Documentary declined in post-war America and avant-garde film enjoyed a brief vogue, allowing veterans of the left to offer their formalist wares under a new name.

Muscle Beach exists today as a tantalizing abberation. For the most part, however, Lerner was a technician for hire. He photographed The Land for Flaherty and acted as a “production associate” for Robot Monster. (The latter credit is too obscure or too embarrassing for inclusion in Jan-Christopher Horak’s Lovers of Cinema, which otherwise provides the most comprehensive Lerner filmography I’ve seen. It would irresponsible to stress Lerner’s contribution to Robot Monster, but the recovering auteurist in me can’t help but note that Robot Monster and City of Fear describe the perils of atomic annihilation more poignantly than any of their Hollywood contemporaries.)

Careers, Clues, and the Blacklist

With no book or article devoted to Lerner, we can only piece his career together through anecdotes and off-hand citations in memoirs and histories of the documentary. In fact, he seems to have been something of a radical gadfly. He was Woody Guthrie’s conduit to Hollywood as the folk singer tried (unsuccessfully, at least during his lifetime) to bring Bound for Glory to the screen. He established Fritz Lang’s entrée into the left-wing New York intelligentsia and the two became so close that Lerner advised Lang that his wife had become “a little suspicious of our (ahem) relationship.” Lerner compiled the first collection of Harry Alan Potakmin’s criticism and produced the frame enlargements for Jay Leyda’s English edition of Eisenstein’s Film Form. He facilitated off-beat gigs for radical friends, as when he hired Henwar Rodakiewciz, Alexander Hackenschmied, and Roger Barlow for OWI projects or commissioned the artists at UPA to animate the menstrual cycle for a junior high sex ed film. He was briefly consulted to polish up Emile de Antonio and Daniel Talbot’s Point of Order, before the filmmakers recognized that Lerner’s professionalism was too tidy and his fee too high.

Allegedly, Lerner was also one of the USSR’s Manhattan Project moles. (Per Venona: Exposing Soviet Espionage in America, Lerner resigned from OWI after a counterintelligence agent caught him photographing UC Berkeley‘s cyclotron without authorization.) Less speculative is the recognition that Lerner’s whole social sphere in the ’30s and ’40s existed on the radical-Communist-Popular Front axis—associations that immediately raise the question of Lerner’s fate during the era of the blacklist.

Allegedly, Lerner was also one of the USSR’s Manhattan Project moles. (Per Venona: Exposing Soviet Espionage in America, Lerner resigned from OWI after a counterintelligence agent caught him photographing UC Berkeley‘s cyclotron without authorization.) Less speculative is the recognition that Lerner’s whole social sphere in the ’30s and ’40s existed on the radical-Communist-Popular Front axis—associations that immediately raise the question of Lerner’s fate during the era of the blacklist.

Lerner is often reflexively described as a blacklisted filmmaker, but the exact nature of his predicament in this period is difficult to substantiate. He received a director credit on some low-budget, independent projects in the early ’50s (Man Crazy, Edge of Fury). Lerner’s name is missing from the indices of such comprehensive blacklist histories as Naming Names and The Inquisition in Hollywood. Nevertheless, his output in the ’50s does have some of the familiar characteristics of careers destroyed by HUAC: minor gigs on low-budget junk and periods of official inactivity. Like many blacklistees, Lerner might have been officially unemployable, but he was still recognized as a professional who could fix disastrous projects for the studios. Phillip Yordan, who acted as a notoriously unscrupulous front for many blacklisted artists, employed Lerner as his go-to fixer.

Even if Lerner himself experienced fewer career setbacks than his blacklisted colleagues, he essentially worked under the same pressures, in the same milieu. His daughter Margery attended the Westland School, a progressive haven for the children of the blacklisted. (“We were definitely guinea pigs,” she recalled to the Los Angeles Times. “Many of us shared the common bond of knowing our dads were blacklisted or in jail, so … we were in the boat together.”) Appropriately enough, Lerner worked as an uncredited editorial supervisor on Spartacus, the unruly superproduction that broke the blacklist. (He would later perform a similar task on Scorsese’s New York, New York; he died during post-production and Scorsese dedicated the film to his memory.)

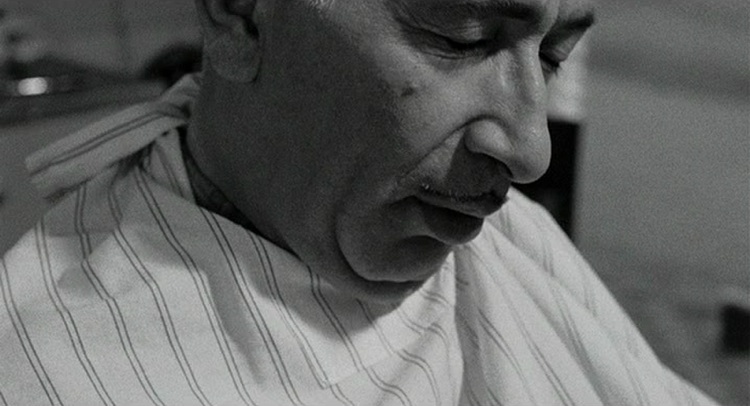

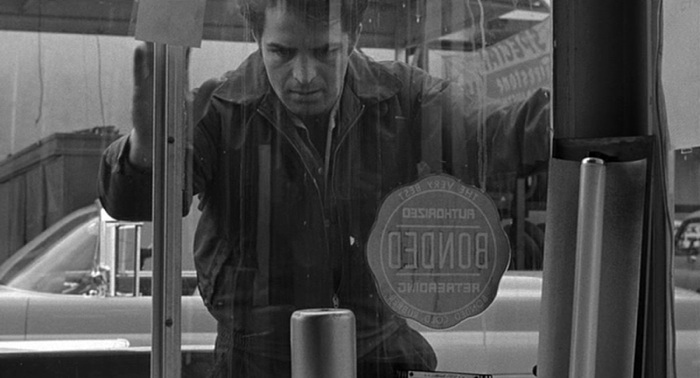

During the tail end of the blacklist period, Lerner managed to direct Murder by Contract and City of Fear for Columbia. Were these productions simply so cheap that they flew in under the political radar? Neither has any hectoring socialist monologues, but they nevertheless manage to say deeply unsettling things about pax Americana. These companion films are a world away from the stylized, Expressionist tangle of post-war film noir, locating their violence in unassuming, sunny gas stations, barber shops, and bungalows. In some ways, Murder by Contract stands as the logical culmination of the post-war ‘business noir’ cycle (Force of Evil, I Walk Alone, Monsieur Verdoux), but worked over with a post-Beatnik sensibility that’s considerably more nihilistic than its predecessors. (Vince Edwards states early on that corporate prerogatives and organized crime are essentially indistinguishable.) Contra Maddow, both films demonstrate that Lerner did have good instincts about camera placement. Lerner and Edwards also brought out the best qualities in each other, jointly advancing a low-key style that anticipates Jim Jarmusch.

During the tail end of the blacklist period, Lerner managed to direct Murder by Contract and City of Fear for Columbia. Were these productions simply so cheap that they flew in under the political radar? Neither has any hectoring socialist monologues, but they nevertheless manage to say deeply unsettling things about pax Americana. These companion films are a world away from the stylized, Expressionist tangle of post-war film noir, locating their violence in unassuming, sunny gas stations, barber shops, and bungalows. In some ways, Murder by Contract stands as the logical culmination of the post-war ‘business noir’ cycle (Force of Evil, I Walk Alone, Monsieur Verdoux), but worked over with a post-Beatnik sensibility that’s considerably more nihilistic than its predecessors. (Vince Edwards states early on that corporate prerogatives and organized crime are essentially indistinguishable.) Contra Maddow, both films demonstrate that Lerner did have good instincts about camera placement. Lerner and Edwards also brought out the best qualities in each other, jointly advancing a low-key style that anticipates Jim Jarmusch.

We can call Murder by Contract and City of Fear the summit of Lerner’s work, but such a declaration would impose a linear orderliness on an essentially unruly career. (These low-budget films also received scant recognition in their own time and hardly advanced Lerner’s professional reputation.) Like all of Lerner’s output, they attest to the singular life of a political survivor. As Andrew Sarris would say, Irving Lerner is most assuredly a subject for further research.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society screens Irving Lerner’s A Place to Live, Muscle Beach, and City of Fear in vault prints from the Academy Film Archive and Sony Pictures Repertory at the Portage Theater on March 27. Please see our current calendar for more information. Special thanks to Chris Lane, Jim Harwood, Mark Toscano, May Haduong, Cassie Blake, and Betsy Strick.

FOR FURTHER READING

Cray, Ed. Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001.

Ellis, Jack C. and Betsy A. MacLane. A New History of Documentary Film. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2005.

Gordon, Bernard. Hollywood Exile: or How I Learned to Love the Blacklist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001.

Haynes, John Earl and Harvey Klehr. Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Horak, Jan-Christopher, ed. Lovers of Cinema: The First American Avant-Garde Film, 1919 – 1945. Madion: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995.

Kline, Herbert, ed. New Theatre and Film, 1934 – 1937: An Anthology. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985.

McGillan, Patrick. Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

McGilligan, Patrick and Paul Buhle. Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Potamkin, Harry Alan. The Eyes of the Movie, ed. Irving Lerner. International Pamphlets No. 348, 1934.

Rose, Marla Matzer. Muscle Beach: Where the Best Bodies in the World Started a Fitness Revolution. Los Angeles: LA Weekly Books, 2001.

Rose, Peter Isaac, ed. The Dispossessed: An Anatomy of Exile. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005.

Rotha, Paul and Sinclair Road & Richard Griffith. Documentary Film, Third Ed., Rev. and En. Glasgow: R. MacLehose & Co. Ltd., 1952.

Sarris, Andrew. The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929-1968. New York: Dutton, 1968.

Talbot, Toby. The New Yorker Theater and Other Scenes from a Life at the Movies. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.