“Film is Dead,” proclaimed one Logan Square art gallery last February, referring not only to the imminent end of film manufacture, but more broadly to moment when ‘film’ lost its currency and accuracy as short-hand for a diverse range of artistic activities. If everybody’s shooting on video/digital/data, then why persist in applying the genteel label of film to anything with the slightest genetic relation to sprocket-and-emulsion-based celluloid?

It’s an important question, albeit one that might be posed a bit less antagonistically. After all, film gains about as much from being associated with gallery installations as video artists do from being confused for 16mm cinematographers. Greater medium specificity and more precise vocabulary ultimately help everybody.

Or so we think. We could be content with these directives if artists themselves weren’t so interested in confounding these distinctions and boundaries. Consider Ken and Flo Jacobs’s recent Nervous Magic Lantern events. The Jacobs presented one such performance at the University of Chicago Film Studies Center last year; I caught a similar one at the Pacific Film Archive in 2009. The experience is akin to being inside an aquarium, or perhaps a particularly languid cabinet of curiosities. Chunky colors and object-like masses float across the screen, accompanied by a selection of unclassifiable records that retain the musk of a certain Greenpoint junk shop.

Or so we think. We could be content with these directives if artists themselves weren’t so interested in confounding these distinctions and boundaries. Consider Ken and Flo Jacobs’s recent Nervous Magic Lantern events. The Jacobs presented one such performance at the University of Chicago Film Studies Center last year; I caught a similar one at the Pacific Film Archive in 2009. The experience is akin to being inside an aquarium, or perhaps a particularly languid cabinet of curiosities. Chunky colors and object-like masses float across the screen, accompanied by a selection of unclassifiable records that retain the musk of a certain Greenpoint junk shop.

Manohla Dargis has outlined the importance of the Nervous Magic Lantern concept as well as anyone:

“I have no idea what I’m watching,” I scribbled into my notebook. I was more right than I knew.

What I watched was beautiful, hypnotic, mysterious and as close to a representation of three-dimensional imagery as I’ve ever seen without wearing funny glasses. It was pure cinema. As it happens, it was so pure that no celluloid had threaded its way through a projector. I hadn’t been watching a film, after all, or digital images, only light and shadow. Using an illusion machine of his own invention that he calls the Nervous Magic Lantern — an apparatus containing a spinning shutter, a light and lenses that he hides behind a black curtain when he isn’t performing what he calls “live cinema” — he had taken the experience of watching moving images back to its origins….

Now, with the Nervous Magic Lantern, [Jacobs] is re-asking one of the fundamental questions about the art: What is cinema? Is it celluloid? Digital? Movement? Light and shadow?

Chicago’s own Manual Cinema is posing comparable questions.

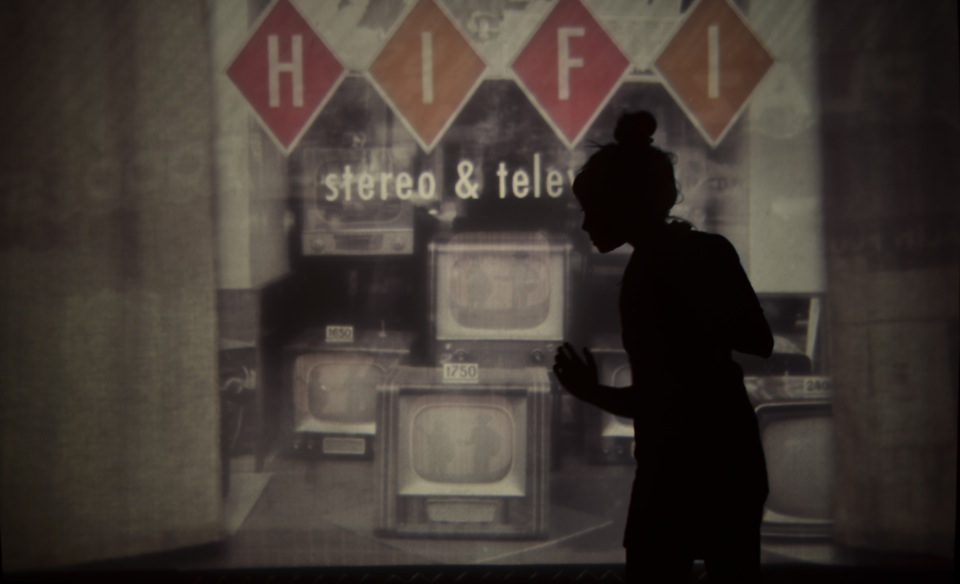

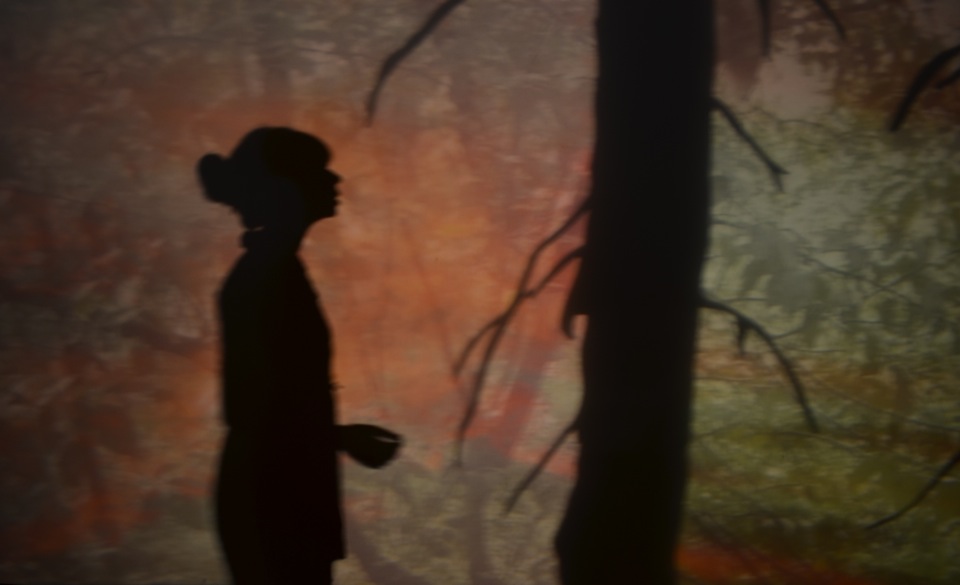

Although Manual Cinema’s principals claim no particular familiarity with film history or theory, their latest show, Lula del Ray, engages them all the same. (Like Jon Moses and Albert Birney’s The Beast Pageant, it’s essentially an outsider’s avant-garde film made by artists without the contaminations of influence or the temptations of imitation.) Pointedly called a ‘feature-length’ production and projected onto a Da-Lite portable screen that approximates the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, Lula del Ray reconstructs cinema grammar from ground zero. Replete with wipes and superimpositions—all achieved with three overhead projectors, their light often obscured and regulated by hands and cardboard shutters—Lula Del Ray is a shadow-puppet performance told in alternating medium close-ups and wide shots. Its light boasts a solidity and texture that can only be recognized as cinematography. Images are fused together as one might expect from a film by Bruce Baillie, but it’s also a projector performance that recalls works like Nicholas Ray’s We Can’t Go Home Again or Harry Smith’s Mahagonny—but again, almost incidentally.

Although Manual Cinema’s principals claim no particular familiarity with film history or theory, their latest show, Lula del Ray, engages them all the same. (Like Jon Moses and Albert Birney’s The Beast Pageant, it’s essentially an outsider’s avant-garde film made by artists without the contaminations of influence or the temptations of imitation.) Pointedly called a ‘feature-length’ production and projected onto a Da-Lite portable screen that approximates the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, Lula del Ray reconstructs cinema grammar from ground zero. Replete with wipes and superimpositions—all achieved with three overhead projectors, their light often obscured and regulated by hands and cardboard shutters—Lula Del Ray is a shadow-puppet performance told in alternating medium close-ups and wide shots. Its light boasts a solidity and texture that can only be recognized as cinematography. Images are fused together as one might expect from a film by Bruce Baillie, but it’s also a projector performance that recalls works like Nicholas Ray’s We Can’t Go Home Again or Harry Smith’s Mahagonny—but again, almost incidentally.

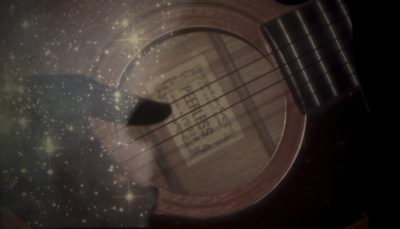

Ultimately, what makes Lula del Ray remarkable is the organic quality of its ideas. Throughout the show, the silhouettes of live actors interact fluidly with the puppets, miniature props, and projected transparencies; a live band strums alongside a pre-recorded soundtrack; expressive flashes of light burst behind the screen, overwhelming and scrambling the delicate on-screen compositions. These tensions are likewise reflected on the thematic and narrative level, especially when a crucial late revelation turns on the recognition of the puppets’ two-dimensionality as a state of being. Rather than demanding a suspension of disbelief, Lula del Ray exalts the reality of surfaces. It’s about puppetry and, by natural extension, cinema. We’re never less than totally aware of the artisanal craft at work, but somehow the show manages to make a singular case for a very different kind of (mass) cultural experience. Lula del Ray asks us to accept the physical and emotional integrity of machine-art. Cinema becomes a form of empathy—understanding through light.

Lula del Ray uses no film, but its exquisitely material sense of cinema struck me as completely simpatico with the interests and aims of the Northwest Chicago Film Society.

Lula del Ray uses no film, but its exquisitely material sense of cinema struck me as completely simpatico with the interests and aims of the Northwest Chicago Film Society.

I interviewed Drew Dir, Manual Cinema member and co-director and co-designer of Lula del Ray, about these issues earlier this week.

KW: You’ve talked about Manual Cinema’s work as an experiment in cinematic time—as if there’s a temporal dimension that is unique to cinema. What distin- guishes it from theater?

DD: Because we’re working exclusively on a screen, and because the overhead projectors stand in for cameras, we’re constructing narrative using editing and montage versus the usual tools of Aristotelian drama (contiguous time and place, etc.). In that sense, we think of time cinematically—I suppose I should qualify that by saying we think of time in terms of conventional narrative cinema. Of course, the audience is also always aware that there are people behind the screen making each and every one of the 233 shots by hand, so that informs the audience’s experience of time in a different way—it combines the lightness of cinema with the heaviness of theater.

KW: The principals in Manual Cinema all come from theatrical and musical backgrounds, but your productions are, of course, also explicitly addressing cinema. Is this a tribute, a corrective—returning the idea of cinema to a more productive origin point—or something else entirely?

DD: I don’t think any of us thought of it in that way when we started. Our company member Julia Miller was the instigator, and her starting point was puppetry. It’s actually been film people who have recognized those ideas in our work and named them for us, and the significance of our name—Manual Cinema—is sort of growing on us as time goes by. In fact, the people most interested in our work tend to be filmmakers and cinema aficionados, and there’s an affinity there that we take seriously and we’re still processing what it means for the work. There’s another group in Chicago we’re friends with called Screen Door who are producing what they call “live movies,” and one of their artists, Jack Mayer, very much thinks of the work he does as restoring or reviving cinema with liveness, but he’s a filmmaker, and he has a different investment in the medium and its fate than we do.

KW: Manual Cinema tends to talk about Lula del Ray as a particular kind of narrative theater, but I found it equally engrossing as an avant-garde film, with strategies that recall the work of artists like Pat O’Neill and Bruce Baillie. Did Manual Cinema have any cinematic reference points during the planning of Lula del Ray?

DD: At least in terms of the cinematography of the piece—if you want to call it that—it’s all based on our own ordinary consumption of Hollywood film: Wes Anderson, Pixar, Spielberg. For the most part our influences are pretty populist. For our previous show, Ada/Ava, which was a kind of fantastical psychological thriller, we did think explicitly of Hitchcock’s Vertigo. And many people have pointed us to Lotte Reiniger’s animated films, though I feel bad admitting that I haven’t yet sat down to watch them.

KW: The projectors are part of your performance—and in earlier iterations of Lula del Ray, you’ve allowed the audience to see the puppeteers at work, hunched over these light machines. I think that most of us haven’t given much consideration to overhead projectors since middle school biology class—and certainly few appropriate them as instruments of art. What is it about these machines that prompted Manual Cinema to build a concept around them?

DD: Our first show used one overhead projector; on our second show we added another, and in Lula del Ray we use three. We can’t really claim credit for rediscovering the overhead projector, though. Especially among our generation of Chicago theater artists, they’re actually unusually prevalent. Redmoon Theater, with whom some of our members have worked, were really pioneers in establishing their use in shadow puppetry, and you can find performance artists all over the country using them to make work. We’re perhaps unusual in that we’ve committed our entire artistic project to working with them. The thing is that we already take them for granted; that is, we don’t think of their use as a “concept.” To us, they’ve simply become our weapon of choice, and we take pride in the fact that we’ve learned a lot about what they can do and how to tell stories with them.

DD: Our first show used one overhead projector; on our second show we added another, and in Lula del Ray we use three. We can’t really claim credit for rediscovering the overhead projector, though. Especially among our generation of Chicago theater artists, they’re actually unusually prevalent. Redmoon Theater, with whom some of our members have worked, were really pioneers in establishing their use in shadow puppetry, and you can find performance artists all over the country using them to make work. We’re perhaps unusual in that we’ve committed our entire artistic project to working with them. The thing is that we already take them for granted; that is, we don’t think of their use as a “concept.” To us, they’ve simply become our weapon of choice, and we take pride in the fact that we’ve learned a lot about what they can do and how to tell stories with them.

KW: Film collectors tend to speak of 16mm and 35mm projectors they trust and those they don’t. (I like Kodak Pageants myself.) There’s a sense of connoisseurship but also a respect for a certain strain of industrial craft. How much care goes into selecting the overhead projectors? How does Manual Cinema procure them?

DD: Our favored model is the 3M 910 overhead projector. We currently own about ten of them. They’re useful for us because they can be adapted for two different lens configurations depending on how large we’d like to throw the projection. They’re also bulky, so there’s a lot of “off-stage” surface, which allows the puppeteers to keep their shadow puppets “in the wings,” and they’re sturdy, so we can put a lot of weight on them in performance. We source them from eBay and craigslist; I’m constantly scouring craigslist for the right models, and by now the collection we have comes from all over the country. The difficult part is sourcing replacement lenses, which we get from an obsolete electronics warehouse outside of Pittsburgh called MB Electronics. I hope they appreciate the shout-out.

DD: Our favored model is the 3M 910 overhead projector. We currently own about ten of them. They’re useful for us because they can be adapted for two different lens configurations depending on how large we’d like to throw the projection. They’re also bulky, so there’s a lot of “off-stage” surface, which allows the puppeteers to keep their shadow puppets “in the wings,” and they’re sturdy, so we can put a lot of weight on them in performance. We source them from eBay and craigslist; I’m constantly scouring craigslist for the right models, and by now the collection we have comes from all over the country. The difficult part is sourcing replacement lenses, which we get from an obsolete electronics warehouse outside of Pittsburgh called MB Electronics. I hope they appreciate the shout-out.

KW: I have the sense that we’re living in an age that simultaneously mourns the passing of an analog world and commodifies what’s left. (You can walk up Milwaukee to Urban Outfitters and find a selection of 35mm still camera film promoted as DIY chic, for example.) Is there a progressive, non-nostalgic place for hand-crafted art?

DD: Manual Cinema is actually working with two obsolete but nostalgic technologies: overhead projectors and shadow puppetry. As a result, audiences bring a lot of their own nostalgia to our shows. We acknowledge that it’s part of our appeal, but we also try not to dwell on that in the content of our shows. As I said before, we think of it as the medium we’ve chosen, and we try to respect it in the same way other artists respect film or video or drama. Our hope is that audiences who might be drawn in because it seems like a gimmick or a parlor trick will leave with an appreciation of the craftsmanship and the story and the ideas.

Lula del Rey runs through December 16 at The Den Theater (1333 N. Milwaukee Ave, 2nd Floor). Photos courtesy Katherine Greenleaf and Manual Cinema. For more information, see www.manualcinema.com