Our screenings are held at multiple venues around Chicago. This season you can find us at:

• The Music Box Theatre

3733 N Southport Ave — Directions • Parking

Tickets: $11 – $12

• The Auditorium at Northeastern Illinois University (NEIU) (inside of Building E)

3701 W Bryn Mawr Ave — Directions • Campus Map

Tickets: $10

• The Gene Siskel Film Center

164 N State St — Directions • Parking

Tickets: $13

• Constellation

3111 N Western Ave — Directions • Parking

Tickets: $15

Want to attend our screenings but having financial hardships? Contact info@chicagofilmsociety.org

SEASON AT A GLANCE

☆ = Technicolor Weekend March 17-19

January▼

Wed 1/18 at 7:30 PM

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans ……… NEIU

Mon 1/23 at 7:00 PM

Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! ……… Music Box

February ▼

Wed 2/1 at 7:30 PM

Weekend ………… NEIU

Wed 2/8 at 7:00 PM

Forbidden Paradise ……… Music Box

Mon 2/13 at 7:00 PM

Zabriskie Point ………… Music Box

Wed 2/22 at 7:30 PM

The Black Cat ………… NEIU

March ▼

Fri 3/3 at 8:00 PM

Short Threads w/ Larry Gottheim …… Constellation

Mon 3/6 at 7:00 PM

Tokyo Drifter ………… Music Box

Fri 3/17 at 6:00 PM ☆

The Wizard of Oz …… Gene Siskel Film Center

Fri 3/17 at 8:30 PM ☆

Bulworth …… Gene Siskel Film Center

Sat 3/18 at 3:00 PM ☆

Technicolor Shorts Program …… Gene Siskel Film Center

Sat 3/18 at 5:30 PM ☆

Gunman’s Walk …… Gene Siskel Film Center

Sat 3/18 at 8:00 PM ☆

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service …… Gene Siskel Film Center

Sun 3/19 at 3:00 PM ☆

Interlude …… Gene Siskel Film Center

Sun 3/19 at 5:30 PM ☆

Artists and Models …… Gene Siskel Film Center

Sun 3/26 at 5:00 PM

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse ……… Music Box

April ▼

Fri 4/7 at 8:00 PM

The Restored Films of Edward Owens ……… Gene Siskel Film Center

Sat 4/15 at 2:00 PM

Kentucky Pride ……… Music Box

Wed 4/19 at 7:30 PM

Working Girls ………… NEIU

Mon 4/24 at 7:00 PM

Runaway Train ………… Music Box

Wednesday, January 18 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

SUNRISE: A SONG OF TWO HUMANS

Directed by F.W. Murnau • 1927

“This song of The Man and his Wife is of no place and every place. You might hear it anywhere at any time. For wherever the sun rises and sets, in the city’s turmoil or under the open sky on the farm, life is much the same: sometimes bitter, sometimes sweet.” This prologue appears at the start of Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans and sets the stage for the strange and wonderful film that follows. Sunrise is simultaneously a culminating work of silent melodrama, an experiment in cinematic Esperanto, a universalist fable that oscillates between the poetic and the pretentious, and a cacophonous ode to modern life. (It also boasts unfathomable digressions, including a pig getting tipsy on table wine.) Western hunk George O’Brien stars as The Man, a loutish romantic whose affair with The Woman from the City (Margaret Livingston) gives him the idea to murder his Wife (Janet Gaynor). Unable to carry out his heinous plan, the Man attempts to reconcile with his Wife, who is surprisingly obliging under the circumstances. German maestro F.W. Murnau was hired by William Fox with the proviso that he inject Art into Hollywood studio filmmaking, and he was given a freer hand than any red-blooded American ever would have enjoyed. The industry noticed: Sunrise won the first (and only) Academy Award for Best Unique and Artistic Production, and continues to influence Hollywood and avant-garde filmmakers alike. With its unconventional and imaginative soundtrack, Sunrise also suggested a more ethereal future for the talkies than Al Jolson minstrel numbers, while inaugurating the 1.19:1 Movietone aspect ratio. (KW)

95 min • Fox Film Corp • 35mm from Criterion Pictures, USA

Preceded by: “Glee Worms” (Ben Harrison, 1936) – 7 min – 35mm

Monday, January 23 @ 7:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

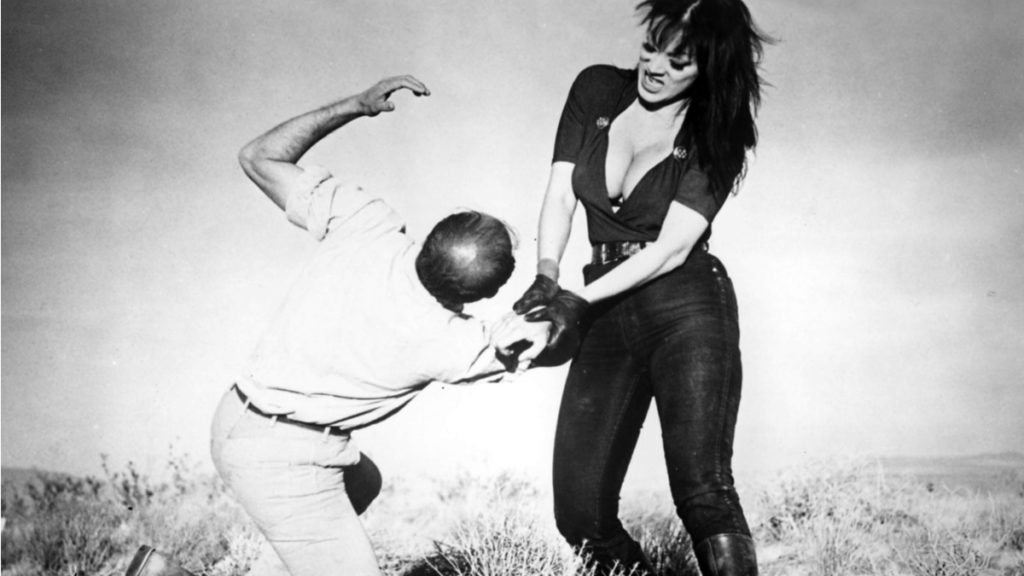

FASTER, PUSSYCAT! KILL! KILL!

Directed by Russ Meyer • 1965

“Let’s examine closely this dangerously evil creation, this new breed, encased and contained in the supple skin of woman.” Ostensibly members of this “new breed,” Varla (Tura Satana), Rosie (Haji), and Billie (Lori Williams) are introduced dancing in fringed bikinis for a crowd of braying perverts, the only moment across 80-odd minutes that the trio at the center of Russ Meyer’s cultishly revered drive-in classic are at all pliant to the whims of men. Before the opening credits even begin to roll, the three of them are careening wildly through the desert in a pack of sports cars, a prelude to the terror they’ll sow across the Mojave. Things first begin to go awry when a naive, car-crazy young couple are goaded into racing Varla and unwittingly find themselves on the receiving end of her fatal wrath. They really spin out of control once the girls decide to pay a visit to a deranged, woman-hating old man sitting on a fortune just down the road. Few purveyors of smut across film history have proved themselves as dedicated to the craft of cinema as Meyer, whose paeans to mazophilia could always be relied on for crackling wit, airtight editing, and a fetishist’s sense for perversely striking visual compositions. Hailed by John Waters as “beyond a doubt, the best movie ever made,” Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! may just be the apotheosis of Meyer’s art, a relentlessly quotable entertainment machine that stands with the very best in American popular cinema. “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to violence.” (CW)

83 min • EVE Productions Inc. • 35mm from CFS collections, permission R.M. Films

Preceded by:

SCORPIO RISING

Directed by Kenneth Anger • 1963

An alternately sumptuous and seamy portrait of ’60s motorcycle culture coursing with libidinal energy, Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising became an underground cause célèbre for its frenetic editing, provocative juxtapositions of Christian and Nazi iconography with long-forgotten bits of American cultural detritus, and revolutionary use of pop music. Shortly after its release, Scorpio Rising became the subject of a landmark obscenity trial based around the film’s purported homosexual content. (As undeniably homoerotic as the film is, Anger maintains that all of the men featured are straight.) Now firmly ensconced in the queer cinema canon, Scorpio Rising was added to the National Film Registry in 2022, an institutional corrective that’s done little to blunt its subversive power. (CW)

28 min • 16mm from Canyon Cinema

Wednesday, February 1 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

WEEKEND

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard • 1967

In French with English subtitles

A dapper pseudointellectual with counterculture ties inclined to making cryptic, self-contradictory pronouncements, Jean-Luc Godard in the 1960s was the closest any film director had come at that point to being a genuine rock star, a Bob Dylan for the arthouse set. While there are no shortage of masterpieces to be found across the entirety of his nearly 70-year career, it’s the run of 15 features he directed between 1960 and 1967 that forever cemented Godard’s legacy as one of cinema’s major practitioners and an artist capable of reinventing the medium with every new film. This string ended with Weekend, the last narrative feature Godard directed ahead of more than ten years spent in obscurity, futzing with video experiments and collectively authored works. A self-consciously terminal provocation, Weekend found Godard leagues away from the movie-mad whimsy of his earliest work, beginning with the title card “A FILM FOUND IN A GARBAGE DUMP” and concluding with another that simply reads “END OF CINEMA.” While the social and metaphysical fabric of France slowly unravels around them, a bourgeois couple make their way through a countryside dotted with apocalyptic carnage, encountering a cross section of imagined literary creations, 20th century wizards, Marxist cannibals, and even-shriller members of their own class, all of whom they’ll belligerently insult and sometimes attempt to murder with varying effectiveness. Underrated as a director of comedy, Godard laces these narrative confrontations with humor that ranges from astringent to scatological, an assurance that every laugh he can elicit will sting as much as possible. (CW)

104 min • Les Films Copernic • 35mm from Janus Films

Preceded by: “Faces in Crashes” (Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 1982) – 10 min – 35mm

Wednesday February 8 @ 7:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

FORBIDDEN PARADISE

Directed by Ernst Lubitsch • 1924

With live piano accompaniment by David Drazin

Pola Negri had achieved international fame in the elaborate historical epics she made under Ernst Lubitsch’s direction in Germany, but her Hollywood career had gotten off to a slow start. Lubitsch had already begun refining his style for the American studio system, crafting smaller, more intimate human comedies that received rapturous critical notices. They reunited for Forbidden Paradise, a startling amalgam of old and new. Negri stars as Queen Catherine, the monarch of a Balkan backwater where misogynist Bolsheviks conspire to overthrow her empire of sex. Luckily, Catherine commands a loyalist brigade of officers who have earned “The Order of the Star” for personal services rendered to the queen. When one of Catherine’s lieutenants (Rod La Rocque) defects to the revolutionaries, she must lean upon her chancellor (Adolphe Menjou) and her checkbook to restore some semblance of order. Forbidden Paradise was greeted as another Lubitsch tightrope trick that promised to “please the more or less worldly-wise audience without any doubt,” per Photoplay, while “the unsophisticated ones will not be entirely ruined morally by it.” One of Lubitsch’s rarest films, Forbidden Paradise long circulated only in fragmentary, incoherent prints, now consigned to the ash heap of history thanks to this new “Order of the Star”-worthy restoration. Restored by The Museum of Modern Art and The Film Foundation with funding provided by Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. (KW)

80 min • Paramount Pictures • 35mm from the Museum of Modern Art

Preceded by: Mutt & Jeff in “Bombs and Bums” (Charles Bowers & Bud Fisher, 1926) – 7 min – 16mm

Monday, February 13 @ 7:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

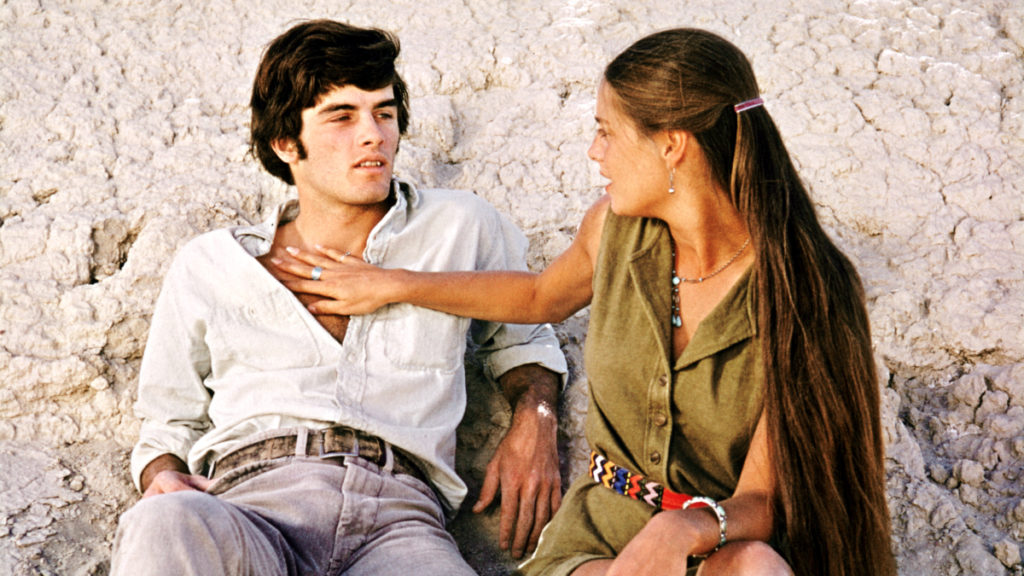

ZABRISKIE POINT

Directed by Michelangelo Antonioni • 1970

For a brief moment after his first English-language effort Blow-Up became a surprise hit, Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni was actually considered a bankable property in Hollywood. It was during this time that the director encountered a news report of a young man in Arizona who went for a joy ride in a small plane only to be shot to death when he returned it. From this foundation, Antonioni would construct Zabriskie Point, an unruly mosaic surveying the clash between all-American consumerism and an ascendent youth culture bent on revolution. Ostensibly anchored by the budding desert romance between fugitive plane thief Mark and alienated office temp Daria (played by nonactors Mark Frechette and Daria Halprin), Zabriskie Point spends roughly equal amounts of time delineating its plot, basking in the natural splendor of its titular locale, and creeping through the blighted sprawl of suburban Los Angeles, spreading further and further like a rash. Confident they had another Easy Rider on their hands, MGM budgeted Zabriskie Point at a lavish $7 million, a decision that appeared to be the height of folly once it premiered to savage reviews and dismal returns. Before the film even left theaters, though, its cult reclamation had begun, bewitching a portion of the very youth audience it was produced for with its oddball narrative and beautifully alien CinemaScope imagery. Some five decades on, Zabriskie Point has aged far better than most contemporaneous studio efforts, a work of genuine big screen spectacle made special for the anti-capitalists. With music by Pink Floyd, The Grateful Dead, The Rolling Stones, John Fahey, and an absolute scorcher of a title theme sung by Roy Orbison. (CW)

110 min • M-G-M • 35mm from Park Circus

Preceded by: God Respects Us When We Work, But Loves Us When We Dance (Les Blank, 1968) – 20 min – 16mm from Canyon Cinema

Wednesday, February 22 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

THE BLACK CAT

Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer • 1934

The Black Cat is one of the freakiest of the Universal horror films, and it’s the first (and arguably the best) to feature both Béla Lugosi and Boris Karloff, with the studio whipping up anticipation for the first on-screen meeting of the horror heavyweights with taglines like “Karloff and Lugosi together!” and “the monster of ‘Frankenstein’ plus the monster of ‘Dracula’!” It was also the first (and last) studio production of the great Edgar G. Ulmer, whose unwillingness “to be ground up in the Hollywood hash machine” (plus an affair with a studio exec’s wife) may have kept him in B pictures – many of which, like Detour and The Man from Planet X, are fantastic – for the rest of his career. In what quickly becomes the honeymoon from hell, a young couple survives a horrific car crash along with a mysterious fellow passenger named Dr. Vitus (a psychiatrist played by Lugosi), and shelter in a nearby Bauhaus-style mansion to recuperate. Turns out not only does the mansion belong to a Satan-worshiping architect (Karloff at his sexiest, it must be said), but he served in the war with Vitus, and they are decidedly not old buddies. In Ulmer’s capable hands, what might have easily been a laughable and crude revenge film becomes a melancholy expressionist portrait of two genteel men willing to inflict untold emotional and physical horrors on each other. And in only 66 minutes! But don’t worry, you’ll have your fun too. It has some of the greatest bathrobes ever printed to celluloid, and as J. Hoberman writes, “The Black Cat somehow eluded the moral enforcers of the Production Code despite its allusions to incest, necrophilia and human sacrifice, not to mention a black Mass staged beneath a stylized crooked cross.” (RL)

66 min • Universal Pictures • 35mm from Universal

Preceded by: “The Hypo-Chondri-Cat” (Chuck Jones, 1950) – 35mm

Friday, March 3 @ 8:00 PM / Constellation

SHORT THREADS with LARRY GOTTHEIM

filmmmaker Larry Gottheim in person!

For more than 50 years now, Larry Gottheim has humbly tilled the edges of the experimental film world. Emerging in the 1970s with a series of acclaimed single-shot experiments, Gottheim’s filmmaking career has consistently evinced a curiosity regarding all manner of artistic forms and a restless creative energy that’s driven him to continually push the boundaries of his own cinema. Gottheim also founded the highly influential Cinema Department at SUNY Binghamton, one of the earliest programs to emphasize personal, artist-driven filmmaking practices and a vital incubator for American avant-garde film. As an artist and educator, his work has forged new paths for emerging filmmakers, subtly expanded the grammar of cinema, and quietly changed the face of American independent film culture. This program brings together a selection of shorts from across Gottheim’s career, beginning with two rigorously minimalist early works: Barn Rushes (1971), an avant-garde landmark comprised of eight 16mm spools documenting a single barn under different light conditions, and Harmonica (1971), a giddy experiment in synchronized sound that stands as perhaps the most joyful structuralist film ever made. Filling out the bill are a pair of dizzying, obliquely autobiographical efforts: Mnemosyne Mother of Muses (1986), a series of metronomically twined remembrances, and The Red Thread (1987), an ecstatically beautiful tangle of overlapping speech and fleetingly captured images that cruises along at the speed of thought. (CW)

Approx run time 80 min • 16mm from Larry Gottheim

Monday, March 6 @ 7:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

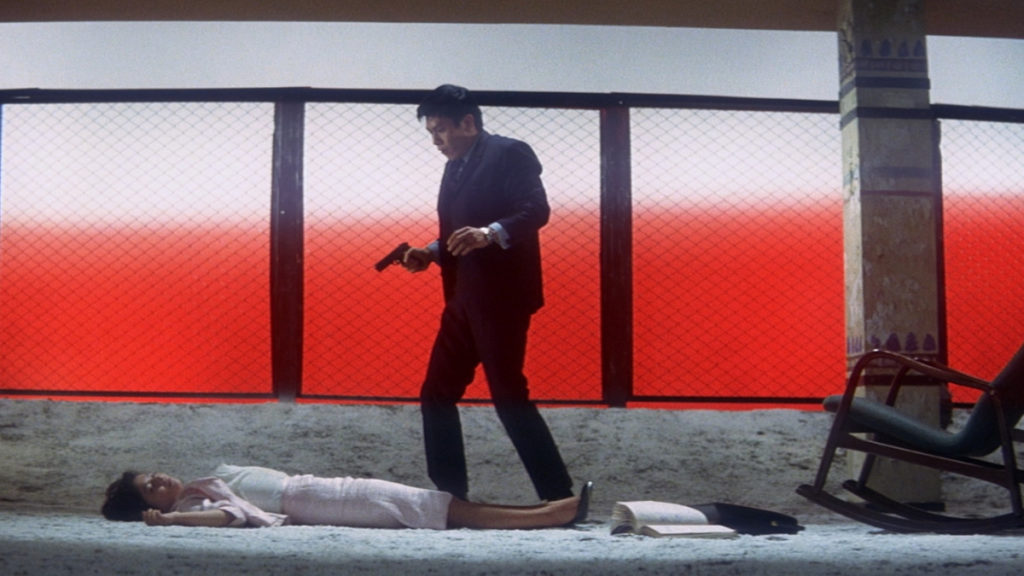

TOKYO DRIFTER

Introduced by William Carroll, author of the new book “Suzuki Seijun and Postwar Japanese Cinema”

Directed by Seijun Suzuki • 1966

In Japanese with English subtitles

With a filmography spanning coming-of-age comedies, sports dramas, sexploitation romps, and more, Seijun Suzuki lays claim to one of the most diverse, and flat-out wackiest, cinematic outputs of any director working in the ’50s and ’60s. Of all the genres he’s worked in, it’s Suzuki’s eccentric take on the yakuza flick that first made him a favorite with cinephiles in the West, with the colorful, hyper-stylized Tokyo Drifter perhaps the most enduring of all his films. “Phoenix” Tetsu (Tetsuya Watari), an enforcer for one of Tokyo’s major crime syndicates, is suddenly set adrift when his boss Kurata decides to disband their gang. Kurata’s retirement, and Tetsu’s subsequent rejection of overtures from former rivals, whips Tokyo’s criminal underworld into a frenzy, and before long Tetsu finds himself personally at war with every gangster in the city. Tokyo Drifter wound up being one of the final films Suzuki directed for longtime studio home Nikkatsu, who by the mid-’60s were growing weary of the director’s uncompromising stylistic quirks. In an attempt to rein Suzuki in, Nikkatsu saddled Tokyo Drifter with a shoestring budget and an imperative to make the film’s title theme, sung by Watari, a hit. (The film was greenlit in part to launch the actor’s singing career.) The studio’s interference had the opposite effect, pushing Suzuki’s trademark pop surrealism to its absolute limit and resulting in a film that’s as outre and absurdly fun as genre cinema gets. (CW)

82 min • Nikkatsu • 35mm from Japan Foundation, permission Janus Films

March 17th – 19th at the Gene Siskel Film Center, we present six features and a program of short subjects in beautiful, vintage Technicolor prints. Not to be confused with the 3-strip Technicolor filming process (abandoned in 1955), the Technicolor printing process involved transferring yellow, cyan, and magenta dyes one by one onto the film base to create the release prints shown in theaters, in a process analogous to offset printing. Prints produced using this method were known for their deep, saturated colors, and the resulting “look” is effectively impossible to replicate using 2023’s digital or analog technologies.

☆ = Technicolor Weekend Screening

Friday, March 17 @ 6:00 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

THE WIZARD OF OZ ☆

Directed by Victor Fleming • 1939

The wonderful, terrifying, beguiling, and marvelous film that gives a shoulder rub to the millions of Americans struggling with impostor syndrome is also one of the landmark Technicolor films. Shot in 3-strip Technicolor, The Wizard of Oz‘s transition from black-and-white to color — which occurs at a reel change — still makes our heart skip a beat. Rereleased numerous times including a digital 3D IMAX version, we’re pleased to present a 1950s Technicolor reissue print from a private collector. (JA)

101 min • M-G-M • 35mm from private collections, permission Park Circus

Friday, March 17 @ 8:30 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

BULWORTH ☆

Directed by Warren Beatty • 1998

Warren Beatty coproduced, cowrote, directed, and starred in this bizarre and often very moving takedown of the American political system and Clinton-era Democratic machine, in which he plays a blubbering, suicidal, lunatic senator who plans his own assassination and spends the days leading up to it doing whatever he wants. Approximately 100 of the 2,000 release prints were made using the revamped IB Technicolor process, which makes full use of cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s expressive color palette.

108 min • 20th Century Fox • 35mm from CFS, permission Disney

Saturday, March 18 @ 3:00 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

TECHNICOLOR SHORTS PROGRAM ☆

This selection of short subjects highlights some of the things Technicolor prints do best: animation (including Porky and Daffy in Chuck Jones’s My Little Duckaroo), travelogues (including Light on East Anglia, printed in England where the water was rumored to give prints even better color), and industrial films. We’ll also present some of our most beautiful Technicolor trailers, give a more in-depth overview of the printing process, and show you what Technicolor prints look like once they’ve been wet. (JA)

Approx 90 minutes • 35mm from CFS and private collections

Saturday, March 18 @ 5:30 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

GUNMAN’S WALK ☆

Directed by Phil Karlson • 1958

Scripted by Frank Nugent (The Searchers), Gunman’s Walk stars Tab Hunter as the drunken, gunslinging son of lawless rancher Van Heflin, and James Darren as his polar opposite brother, a dark, brooding pacifist. Better known for bitter, black-and-white film noirs like 99 River Street and The Phenix City Story, Chicago-born Phil Karlson had the right idea about this widescreen color western: “When I do color, I think in terms of black and white … we know that blood’s going to be awfully red and it’s going to be pretty disgusting when they see it.” This print recently returned to the United States after spending several decades with a collector in Canada. (JA)

97 min • Columbia Pictures • 35mm from CFS, permission Sony Pictures Repertory

Saturday, March 18 @ 8:00 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

ON HER MAJESTY’S SECRET SERVICE ☆

Directed by Peter R. Hunt • 1969

Naturally, the first time the Chicago Film Society shows a James Bond film, we show the most divisive one, thought by some to be the best of the series and others to be among the worst. The first and only appearance of model George Lazenby as 007 features one exquisite action sequence after another, and its reputation has only improved with time. Noted Steven Soderbergh: “Shot to shot, this movie is beautiful in a way none of the other Bond films are.” All of the pre-1970 James Bond films were printed in Technicolor, which was integral to their reputation as lush, garish works of popular cinema. (JA)

142 min • United Artists • 35mm from CFS, permission Park Circus

Sunday, March 19 @ 3:00 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

INTERLUDE ☆

Directed by Douglas Sirk • 1957

An emotionally stunning Technicolor melodrama from the director who basically invented them, Interlude follows the budding romance of June Allyson and conductor Rossano Brazzi, who has a secret wife with a secret problem. At the time, Universal — who released all of Douglas Sirk’s 1950s films —printed some of their titles on Eastman stock and others on Technicolor. Luckily, this obscure and rarely revived title, beautifully shot on location in Germany and Austria, received the preferred treatment. (JA)

90 min • Universal-International • 35mm from CFS, permission Universal

Sunday, March 19 @ 5:30 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

ARTISTS AND MODELS ☆

Directed by Frank Tashlin • 1955

Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Shirley MacLaine, and Dorothy Malone star in perhaps the strongest example of a live action film with the kinetic energy of a cartoon. Much like the Looney Tunes directed by Frank Tashlin, Artists and Models creates a world of deep, saturated colors and absolutely nutty, crazed characters that also feels a lot like a family. Watch with love as Jerry imitates a stork while Dean is in the tub. (JA)

102 min • Paramount Pictures • 35mm from CFS, permission Paramount

Sunday, March 26 @ 5:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

With live musical accompaniment by Maxx McGathey

Directed by Rex Ingram • 1921

The Spaniard Madariaga (Pomeroy Cannon) has made a fortune as a landowner in Argentina, but the paterfamilias of the Pampas can scarcely keep his clan intact, as his two daughters wed French and German suitors and eventually move back to the continent. Only Madariaga’s playboy grandson, the part-time tango instructor Julio (Rudolph Valentino in his star-making turn), embodies the family spirit. But soon an assassination in Sarajevo echoes the prophecy of St. John, cousins take up arms against each other, and the Four Horsemen — Conquest, War, Pestilence, and Death — gallop across the sky. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was confidently adapted from Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s best-selling novel, an epic production that credibly recreates an estate in Bueno Aires and a castle on the Marne in the wilds of Southern California. While dozens of films had cheered on the war as it unfolded, Four Horsemen became one of the first Hollywood films to reflect upon the human, social, and cultural abyss of World War I — and was ably rewarded as one of the major blockbusters of the silent era. No small amount of credit goes to director Rex Ingram and cinematographer John Seitz, who developed an extraordinarily sophisticated aesthetic for the film. “I wanted to get away from the hard, crisp effect of the photograph,” suggested Ingram, “and get something of the mellow mezzotint of the painting … to picture not only the dramatic action, but to give it some of the merit of art.” Critics obliged, and reached for new superlatives, assuring a restive public that movies really could (and should) be treated as art. (KW)

135 min • Metro Pictures • 35mm from Park Circus

Friday, April 7 @ 8:00 PM / Gene Siskel Film Center

Tomorrow’s Promises: The Restored Films of Edward Owens

1966 – 1970

By the age of twenty-one, South Side native Edward Owens had won a scholarship to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studied under Gregory Markopoulos, carved out a precarious place among New York’s queer underground, met Andy Warhol, and made a quartet of distinctive films that screened around the globe. Then his filmmaking career abruptly stopped, never to resume, while the films remained in the collection of the Film-Makers’ Coop, unrented and unseen for thirty-five years. Now newly restored, Owens’s work demonstrates the outsized influence of his mentors but also points the way to a uniquely personal and interior cinema — home movie portraits composed with an almost beatific glow, the subjects simultaneously intimate and larger-than-life. As the only known gay Black filmmaker working during the New American Cinema era, Owens’s work is also an invaluable contribution to a renewed survey of the field, a voice almost completely excluded from the established canon of American avant-garde cinema. (KW)

The Films of Edward Owens were restored in a joint project undertaken by Chicago Film Society, The New American Cinema Group, Inc./The Film-Makers’ Cooperative, and the John M. Flaxman Library at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. This project was made possible with the support of the National Film Preservation Foundation’s Avant-Garde Masters Grant Program and the Film Foundation. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. Restoration: BB Optics; Laboratory Services: Colorlab.

Total program: 81 min • 16mm from CFS Collections

Autre Fois J’ai Aimé Une Femme (1966) – 24 min

Tomorrow’s Promise (1967) – 42 min

Remembrance: A Portrait Study (1967) – 6 min

Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts (1968–70) – 9 min

Learn more about the restoration of these films here!

Saturday, April 15 @ 2:00 PM/ Music Box Theatre

KENTUCKY PRIDE

With live musical accompaniment by Jay Warren

Directed by John Ford • 1925

You think you’ve seen everything, and then you see a silent film narrated by a horse. Following his ostentatious historical epic The Iron Horse (not narrated by a horse, title aside), up-and-coming director John Ford shifted hoofs and made this small-scale, interspecies family saga laid in the pastures of the Bluegrass State. Kentucky Pride follows the life and times of Virginia’s Future, a thoroughbred filly named for the daughter of her first owner, a Southern gentleman (Henry B. Walthall) whose gambling habit continually threatens said future. Following a racetrack accident, Virginia’s Future gets shuffled between a succession of owners: a kindly Irish trainer (Ford regular J. Farrell MacDonald), a farmer, and a cadre of urban junkmen. Offhandedly inventing a sturdy four-legged narrative structure later adopted by Au hasard Balthazar and EO, Kentucky Pride is a sentimental movie with a radically empathetic heart, one that makes a straightforwardly convincing case for equine consciousness and equality. (In the opening credits, “Us Horses” are billed first, including a cameo from real-life champion Man O’ War.) Take it from the horse’s mouth: Ford’s biographer Joseph McBride has championed this film, observing that the “deftness of his craftsmanship in Kentucky Pride — the kind of art that conceals art — keeps this unknown gem fresh and exuberant today.” Preserved by The Museum of Modern Art with support from The Film Foundation and The National Endowment for the Arts. (KW)

78 min • Fox Film Corp • 35mm from the Museum of Modern Art

Wednesday, April 19 @ 7:30 PM / NEIU

WORKING GIRLS

Directed by Lizzie Borden • 1986

Famed feminist filmmaker Lizzie Borden’s Working Girls gives us an intimate, potent, and humorous look into the day-to-day lives of the sex workers in a small brothel in 1980s Manhattan. Borden was inspired to create Working Girls after hearing about the sex work experiences of the cast and crew from her iconic dystopian film Born in Flames, released in 1983. She gathered research from her peers on set and held interviews with other sex workers and their clients. With this perspective Borden gives us insight into a world where sex work is humanized. The film’s middle-class brothel — a set constructed inside Borden’s own loft and shot on 16mm— is not a place of extravagance, but just an almost-normal place to go to work. Arrive for your morning shift, argue with your coworkers about who must deal with the peculiar morning regular, and barely have time for lunch between clients. Our lead Molly — lesbian escort, photographer, and parent — takes us through her workday. She kills time in between clients by talking with her coworkers about their degrees, their aspirations, and if their partners know where they really go to work. They chat about dreaded regulars and compare notes on the “nice” ones. The workday is laced with banal interactions with men and an overbearing boss who asks too much and gives too little. This quotidian approach to a ‘salacious’ subject baffled and angered many reviewers during Working Girls’s improbable 1987 theatrical release courtesy of real-life scum pit Miramax (!), but latter-day viewers have come to appreciate how Borden transformed the male gaze to make us see prostitution in a different and more empathetic light. (TV)

93 min • Alternate Content • 35mm from private collections, permission Janus Films

Preceded by: Trailer for “Working Girl” (Mike Nichols, 1988) – 35mm

Monday, April 24 @ 7:00 PM / Music Box Theatre

RUNAWAY TRAIN

Directed by Andrei Konchalovsky • 1985

Over the years CFS has shown several films perhaps unfairly labeled as the “serious pictures” from the Cannon Group catalog: Jean-Luc Godard’s King Lear, John Cassavetes’s Love Streams, and Andrei Konchalovsky’s Shy People — and we could not in good conscience leave out Runaway Train. Adapted from an original screenplay by Akira Kurosawa, Runaway Train opens in a remote prison in Alaska where the release of well-respected convict and repeat escapee Manny (Jon Voight) from solitary confinement triggers a prison riot. Amid the chaos, Manny escapes again, this time with a tagalong: a young inmate played with rabid puppy energy by Eric Roberts. (To date Roberts has racked up over 700 roles, but he’s truly a sight to behold in the 1980s.) The two men take shelter in an empty locomotive, and when the engineer unexpectedly drops dead they find themselves hurtling through the Alaskan wilderness in an unmanned train with busted brakes, with a sadistic warden who refers to them as “pieces of human waste” hot on their trail. As an action film, it does extraordinary work, offering CGI-free stunts of mind-boggling skill and beauty — trains crashing into trains, people dangling from helicopters, Rebecca De Mornay walking on top of a speeding locomotive — but its work in the philosophical and emotional realm is just as memorable. This is not a film to watch at home, it’s a film to be seen big and loud and bright, to be enveloped and pummeled by. It’s a film that left even Roger Ebert speechless (at least for a moment): “The ending of the movie is astonishing in its emotional impact. I will not describe it.” (RL)

112 min • The Cannon Group Inc. • 35mm from Park Circus

Preceded by: Popeye in “Onion Pacific” (Dave Fleischer, 1940) – 6 min – 16mm

Programmed and Projected by Julian Antos, Becca Hall, Rebecca Lyon, Tavi Veraldi, Kyle Westphal, and Cameron Worden.

Research Associate: Mike Quintero

Heartfelt thanks to:

Shayne Pepper, Cyndi Moran, Robert Ritsema, Jose Aguinaga of Northeastern Illinois University; Brian Andreotti & Ryan Oestreich of the Music Box Theatre; David Antos; Brian Belovarac of Janus Films; James Bond of Full Aperture Systems; Dennis Chong, Jesse Chow, Liam Berney, Jason Jackowski, & Eric Chin of Universal; Chris Chouinard of Park Circus; Janice Cowart of RM Films; Amy Crismer of Disney; Justin Dennis of Kinora; Carolyn Faber & April Sheridan of the John M. Flaxman Library of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; Rebecca Fons and Michael Wawzenek of the Gene Siskel Film Center; Larry Gottheim; Cary Haber of Criterion Pictures, USA; Shun Inoue & Maya Sato of The Japan Foundation; John Klacsman & Jed Rapfogel of Anthology Film Archives; Steven Lloyd; Mike Metzger and Malia Haines-Stewart of Block CInema; Jeff Milam of Ecometric Solutions; Seth Mitter of Canyon Cinema; Nicole Muto-Graves, Nolan Chin, Margaret McCarthy, and Mike Reed of Constellation; MM Serra of the Film-Makers’ Coop; Katie Trainor & James Layton of the Museum of Modern Art; and Gabriel Wallace. Particular thanks to CFS research associate Mike Quintero, CFS board members Mimi Brody, Steven Lucy, Brigid Maniates, & Artemis Willis, & CFS advisory board members Brian Block, Lori Felker, & Andy Uhrich.

And extra special thanks to our audience, who make it all possible!