It can be difficult to fit into a short screening intro all the fascinating details our Research Associate, Mike Quintero, uncovers about the films we show — so we’ll be sharing some of his raw research notes here on the blog, in no particular order and without much editing, because it seems a shame to keep them to ourselves. Thanks Mike!

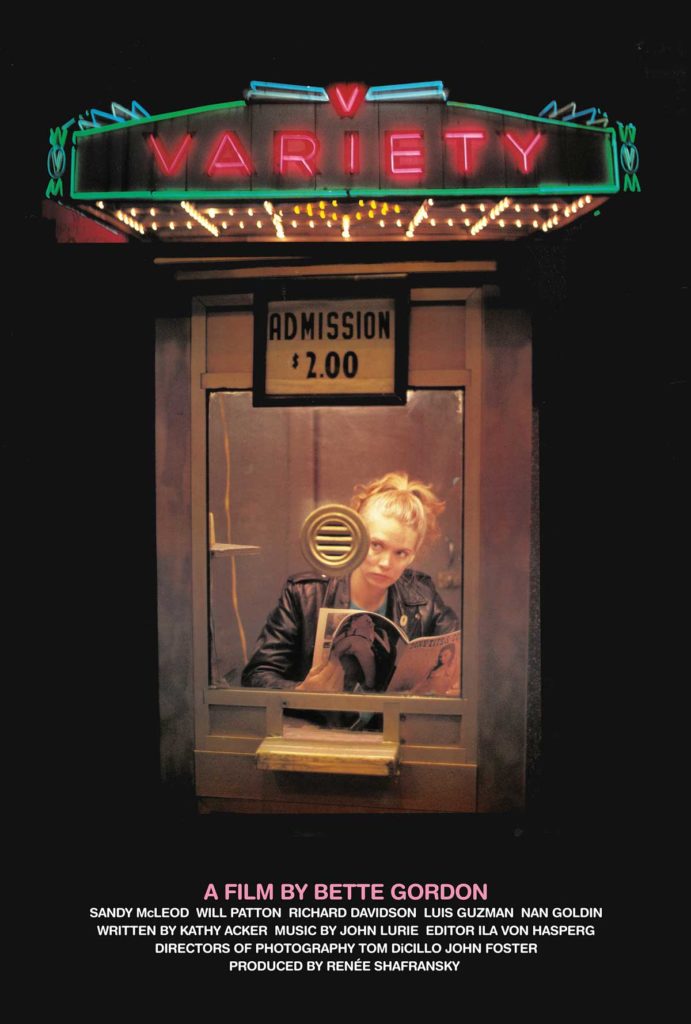

This week’s research notes are about: VARIETY (Bette Gordon, 1983), screened on July 13, 2022 in a 35mm print from Kino Lorber as part of CFS Season 28.

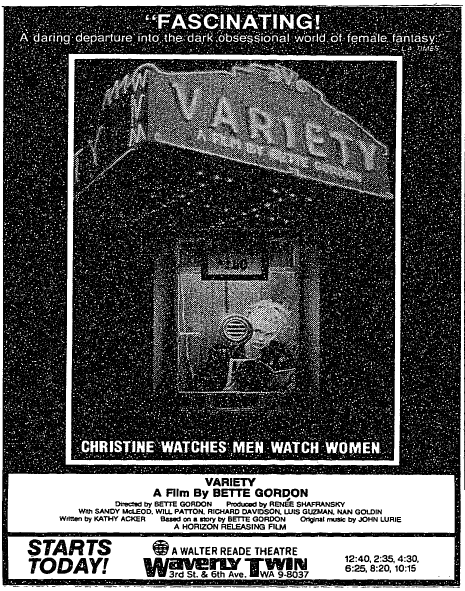

★ Taglines ★

“Christine watches men watch women”

Production Notes:

According to an 1986 article in the New York Times about general troubles financing independent films — for example: a pre-fame Spike Lee is described as almost losing the negative for SHE’S GOTTA HAVE IT for the sake of $2,000 in lab fees, and needing to call everyone he knew to scrounge up the money to prevent the lab from auctioning off the negative — VARIETY cost about $80,000 to shoot, but additional post-production was $30,000.

Funding was provided in part by the West German television network ZDF, via their Kleine Fernsehspiel (literally: “little television play”) program (which also funded early works by Fassbinder, Jim Jarmusch, and Errol Morris, among many others), but was also funded via “family, friends, and the state arts council,” according to producer Renee Shafransky.

From an essay by Rebecca Bengal on photographer Nan Goldin’s influence on film and television in Aperture (July 9th, 2020):

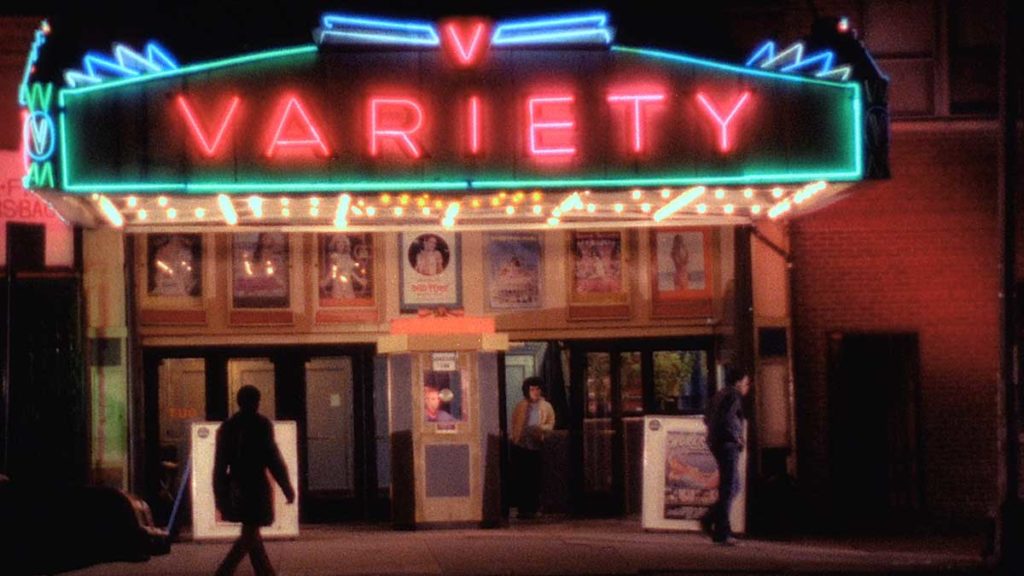

“By the early ’80s, [Nan] Goldin was screening soundtracked slideshows of The Ballad at such venues as the former screening room Rafik and the Mudd Club and tending bar at Tin Pan Alley in Times Square. “That bar really toughened me up,” Goldin recalled. (She eventually quit the day a drunk urinated on her camera: “I screamed like an opera diva—you could hear me all over Manhattan.”) It became one of the central locations for Bette Gordon’s 1983 film noir influenced Variety, named for a former vaudeville house transformed into a porn theater, and spun straight out of the world of The Ballad and the seedy atmosphere of Times Square before its Rudy Giuliani–era Disneyfication. The film’s spirit of downtown artistic collaboration was itself like a mirror of the people Goldin photographed in The Ballad, her family. “They were all bartenders, friends, strippers, workers from the neighborhood. At the time, Kiki Smith was cooking in the kitchen, John Ahearn’s sculptures of people from the Bronx were on the wall,” Gordon once recalled. “They were a mixed group of artists, local sex workers, pimps, street people from Times Square, and film industry people. The woman who owned the bar helped facilitate the shoot, and the location was perfect.” Gordon worked on her treatment with Spalding Gray; his then partner Renée Shafransky was a producer; Kathy Acker wrote the script; and John Lurie created the score. Goldin photographed stills for the film, as she did for Sleepwalk, Sara Driver’s downtown-set film of the same era. In Variety, alongside her good friend Cookie Mueller, Goldin also had an acting role, playing a character who shares her own first name.”

John Lurie from a 1984 interview with David Edelstein in the Village Voice:

“At the Bottom Line several days later, the crowd is sparser and more staid (although it includes Wim Wenders and Tom Waits). “Live music doesn’t make sense anymore,” says Lurie. “I can’t play at any club in New York where the sound’s good and it’s fun to be at. There’s a lotta great musicians in this town, but there’s no scene for them anymore.” The band performs several Lurie compositions from his soundtracks; one seductive melody, from Bette Gordon’s Variety, he’d planned to call “The Blow Job.” “It’s supposed to be a sentimental title but girls seem to hate it, so I might change it to, ‘It Could Be Very, Very Beautiful.’”

Reviews:

“The dialogue is stagy at times, and the elliptical, open-ended plot is full of self-consciously arty touches.” – Larry Kart, Chicago Tribune, 1984

“a painfully underwritten screenplay, and a static, uncommunicative directorial style … the idea that Christine might develop a growing fascination with voyeurism and pornography, while provocative, is something that Miss Gordon is almost entirely unable to articulate in visual terms.” — Janet Maslin, New York Times, 1985

“… more interesting in theory than in practice. It’s a prolonged tease, leading to nowhere — like coitus interruptus going on forever. … But Gordon does have her moments: to convey the grip that men have on life, she photographs a series of rapid-fire handshakes that are downright erotic in their depiction of power and dominance. It’s the sexiest thing in ‘Variety.'” — Joe Baltake, Philadelphia Daily News, 1985

“The movie is always absorbing but it tends to become erratic when it tries to discuss how this non-stop erotica impinges on Christine … More damaging, the movie veers off into an aimless tangent in which Christine dates one of the customers. She suspects him of being in the Mafia, which he is, and starts trailing him all over the New York metropolitan area. This aspect of the film, laid out with tedious repetitions, simply doesn’t mesh with its more central concern. It imparts a variety that Variety doesn’t need.” — Desmond Ryan, Philadelphia Inquirer, 1985

“a subtle feminist critique of pornography … a blank slate, [Christine] is slowly transformed by the pornographic milieu, despite her physical and emotional isolation in a 42nd Street box-office … she becomes so obsessed with one shady customer that she enters his life in pursuit of his dirty secrets. But as this subplot becomes more and more artificial, we realize it’s all a fantasy, as she becomes more and more enmeshed by the world of voyeurism. Gordon’s first feature is intriguing and cleverly crafted. It deserves to be seen by all those interested in feminism or new film.” — Christopher Harris, Ottawa Citizen, 1985

“What sly fun Bette Gordon’s ‘Variety’ is. In this near-surreal, low-budget Manhattan movie, Gordon’s pretty, wholesome-looking heroine, in need of a job, becomes a box-office cashier at a Times Square porno theater, an experience that unleashes her sexual imagination. There’s a zany, intensely visual, odyssey-like quality to ‘Variety’ that recalls ‘Stranger Than Paradise’ and ‘Desperately Seeking Susan’ … ‘Variety is even more complex than ‘Stranger Than Paradise,’ especially in the challenge it raises to the usual feminist view towards pornography, and is equally deserving of a regular run.” – Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times, 1985

“… a bleak but thought-provoking portrait of a world dominated by male power and sexual preferences.” – Christopher Hume, Toronto Star, 1986

“Despite its gender-flipping originality, Bette Gordon’s character study is dreary and tedious. A marginal selection.” – Jeff T. Dick, Library Journal, 1999

“Variety challenges both feminism and pornography, portraying the woman as the voyeur but subtly suggesting that male porn consumption depends on the exclusion of female desire … as odd as it all sounds, it’s a fascinating study of sexual obsession that seems just as relevant now as it did in 1983.” – Lee Parpart, Toronto Globe and Mail, 1999

“Anyone who went to film school had to suffer through Bette Gordon’s Variety, an incoherent rambling about female sexuality told from the viewpoint of a porno theater ticket seller.” – Fred Topel, Video Store Magazine, 2001.

Bette Gordon on VARIETY:

“Although film is produced to be seen, the conditions of screening, for example, the darkened theater, and other narrative conventions give the spectator an illusion of looking in on a private world. The pleasurable structures of looking in the cinema arise from multiple sources: the pleasure of using another person as an object through sight and subjecting their image to a curious and controlling gaze, and also through narcissism and identification with the image seen, for example, with the images of perfect Hollywood stars.

From a feminist perspective, the pleasure of looking in the cinema has been connected with the centrality of the image of the female figure. This has involved an exploration of the way in which sexual difference is constructed in cinema, the way in which the gaze is split (men look, women are looked at), and the representation of female pleasure. It is this notion of female pleasure which interested me when making my film, Variety. Pornography becomes a site of feminist exploration into what it has to say about desire, what kind of fantasies it mobilizes, and how it structures diverse sexualities.

…

The film is concerned with watching at all levels, as the fictional narrative of the young womanʼs voyeurism becomes a metaphor for the way that men watch women not only in pornography but in all cinema. Christine works in a pornographic movie theater as a ticket-seller and becomes obsessed with watching one particular male client. Gradually succumbing to her curiosity, she begins to follow him. Her obsession is voyeuristic, and in this sense can be seen as pornographic. But in this case, the traditional male role (male as voyeur, woman as object) is reversed, positing the woman as voyeur, in an attempt to locate female desire within a patriarchal culture.

…

The ticket booth is a central image in the film: it is a transitional place, in between the theater and the streets. [Christine] is not completely involved in the sex industry, since she is not a dancer or a porno movie actress; she is a ticket-taker and could either leave the sex industry or move more deeply into it. I did not want her to be perceived as a victim.

…[Christine] follows the anonymous client into a porno bookstore, losing sight of him momentarily, and begins to browse through the magazines. An elaborate exchange of looks takes place: men look at her; she looks at them, looking at women, looking. . . . She is out of place in the porn store, a male space. Men often leave when a woman enters an adult bookstore because they are caught in the act of looking.

Three looks operate in mainstream cinema: (1) characters in the film look at each other; (2) the camera looks at what it films; (3) the viewer looks at the screen. Paul Willemen suggests that pornography contains a fourth look: an observer looks at the viewer of pornography, catching him in a taboo act. The fourth look could be the superego or the threat of censorship, directed at the pornographyʼs illicit place in the culture. A woman in a porn store represents the fourth look and so makes men uncomfortable. Other men are complicit, but a woman is not. She is supposed to be the object of their gaze.”

— Issues in Feminist Film Criticism, 1990.

“My films have always focused on the visual aspects of storytelling. I’ve been drawn to stories in which color, texture, and mood are as central to the narrative as character and plot. In VARIETY (US, 1984), my early feature, I linked my visual approach to subject matter. VARIETY is a film about looking, seduction, and voyeurism. I used frames within frames, windows, doorways, and reflections in order to visually capture the idea of looking and being looked at.”

— Framework 59, No. 2, Fall 2018, pp. 152–158.

Release

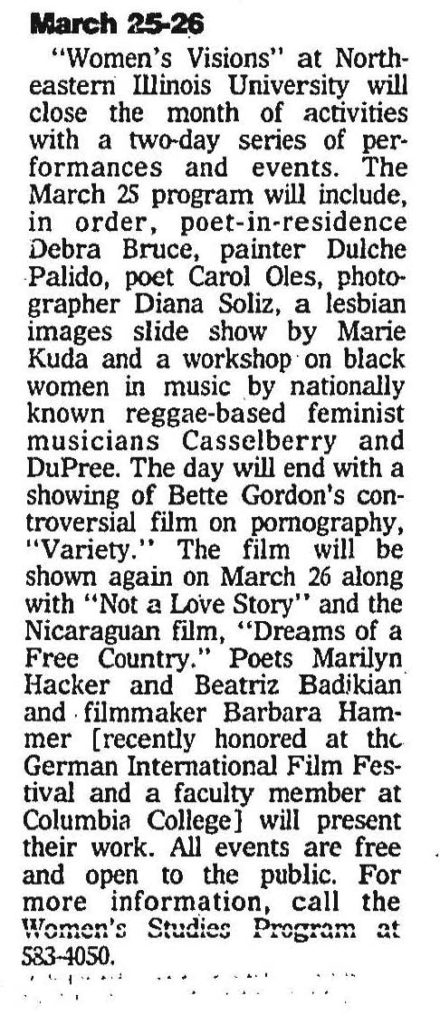

VARIETY received its Chicago premiere at the Film Center in 1984, but this Wednesday’s screening will not be the first time VARIETY has screened at NEIU.

It screened there twice in 1986 as part of the university’s seventh annual showcase for “women’s accomplishments in art, poetry, film and music” titled “Women’s Visions ’86: Women in the Arts.”

According to the Defender, NEIU was the first state university in Illinois to have a formal women’s studies program, which began in 1972. By 1979, according to the Trib, NEIU had three women majoring in women’s studies and eight minoring in it.

This 1990 document shows some of the faculty and classes offered by the school at that time.