It can be difficult to fit into a short screening intro all the fascinating details our Research Associate, Mike Quintero, uncovers about the films we show — so we’ll be sharing some of his raw research notes here on the blog, in no particular order and without much editing, because it seems a shame to keep them to ourselves. Thanks Mike!

This week’s research notes are about: SPAWN OF THE NORTH (Henry Hathaway, 1948), screened on June 29th, 2022 in a 35mm print from Universal as part of CFS Season 28.

★ Taglines ★

“Out of the wild and exciting north roars Paramount’s drama of America’s last untamed frontier! / Romance stormy as the seething Arctic .. spawned in a land of reckless, indomitable women .. of devil-may-care sea rovers .. becking adventure .. flinging their defiance at death on thundering glaciers .. for their booty of love and riches!”

“Stirring drama lashes America’s last untamed frontier!”

“A LOVE STORY .. Stormy as Roaring Arctic Seas!”

“UNTAMED ADVENTURE!”

Production Notes:

In June of 1936, it was announced that director Henry Hathaway (assisted by Richard Talmadge, “the old time silent star of westerns”) had flown to Ketchikan, Alaska to scout locations for what is described as “the pretentious color film ‘Spawn of the North’; screenwriter Grover Jones would follow by train, and a company of 150 (including leads Carole Lombard and John Howard) would follow in July to film outdoor sequences. (Hathaway replaced Walter Wanger, who had been previously associated with the project.)

(The Washington Post noted that “Paramount technicians are all hot over the prospect to film the Northern Lights in color” but that, due to the “electrical disturbances” of the Aurora Borealis, hand-cranked cameras may need to be used instead of the standard motor-driven variety. In the end, however, the film would be produced in black and white.)

Even at this point, the cast seems to be in flux: on June 5th, the New York Times lists “Carole Lombard, Henry Fonda, and Cary Grant” as the stars, on June 6th, the Tribune lists “Carole Lombard and her leading man, John Howard”, and on June 7th, the New York Times notes that Carole Lombard will star, and the studio is negotiating with Cary Grant to take on the male lead.

(By the time the film is released in August 1938, nearly a dozen more actors will have been associated with the film in the press at one point or other, including Gail Patrick, Randolph Scott, Ray Milland, Fred MacMurray, Frances Farmer, Charles Bickford, Leif Erickson, Beulah Bondi, Cecil Cunningham, Georges Rigaud, and Galan Galt — none of whom appear in the film. The actors who actually appear in the film are mostly cast in the six or so months prior to the release of the film, if the newspaper articles about the casting can be believed.)

By June 25th, though, the production had been halted, due to what’s described as the “illness” of Carole Lombard. Lombard’s physicians notified the studio that her health would not permit her to take a nine-week trip to Alaska away from “expert medical attention.”

Paramount then canceled the ocean liner which had been chartered for 90 days to transport the cast and crew to Alaska, reassigned Henry Hathaway and Grover Jones to SOULS AT SEA (which will star Gary Cooper), and reassigned Cary Grant (whose contract had been signed the day before) to another film as well. (The cost of shutting down the production to Paramount is “several thousand dollars,” according to a New York Times article.)

However, according to Larry Swindell’s 1975 biography of Carole Lombard (“Screwball: the Life of Carole Lombard”), Lombard had originally attached herself to the project as part of a covert plan to have the opportunity to co-star in a film with Clark Gable; she then proposed to the studio that Gable be cast as the male lead. When Paramount balked at the cost of having both stars in the film, she lost interest in the project and arranged a medical excuse to extricate herself from the production.

In April 1937, almost a year later, the relaunch of the project was announced. While there is occasional press coverage of the production after that — mostly casting and recasting — it’s not till more than a year later that a pair of New York Times articles (one published in May 1938, the other in September) provide some really tantalizing details about the production of the film.

According to these articles, camera crews, led by associate director Richard Talmadge, had spent months in Alaska filming what are described as “background and transparency shots” or “background and spectacle material.”

Hathaway wrote later that Talmadge’s crew had spent 14 weeks in Alaska and shot nearly 80,000 feet of material from which he could “pick and choose” — and, furthermore, “none of this will go to waste: scenes not used in the picture have been filed in the studio film library and undoubtedly will prove of value later on.”

(He may have been more right than he realized: more than a decade later, Paramount mounted a remake of the film titled ALASKA SEAS. According to Hedda Hopper: “Backgrounds from the original picture will be used, with the new story being told in closeups by the actors. If the experiment works, every studio in town can follow suit. Think how many pictures RKO could make from the footage Orson Welles shot in South America which was never used.”)

For the studio portion of the shoot, Paramount built an immense concrete tank (“enclosed in a black tarpaulin hood that housed a dock, boats jogging on waves, and a half-dozen icebergs”), with a novel rear-projection arrangement: “at the back of the tank are three transparent screens on which three projectors throw the background film, permitting for the first time the use of a wide-angle lens in process work — an accomplishment that prevents the screen from going out of focus. The average transparency lacks depth because of the narrow surface that is rephotographed, and with a twenty-four-millimeter lens, the widest angle possible, the illusion of actuality will be attained.”

The Times described another, even larger tank as well: “with icebergs even more formidable, lightning and hail, boats threading through synthetic mist with a diapason of sirens, ranging from gnawing bass to the waspish.”

(No detail too small, either: Ed Sullivan described in his gossip column the crucial job of one of the grips: “he sits by the side of the tank all day long, and paddles the water with both hands so that the lights will glimmer on the waves.”)

A short essay Hathaway wrote that year for a magazine titled “Photoplay Studies” (p. 137-160) contains some other details about the production:

“A huge Alaskan fishing village set was constructed on the sea coast, about 40 miles south of Hollywood, where the company spent several weeks on location. A fleet of some 25 seine boats was chartered. Other location sets were constructed or “staked out” at Lake Arrowhead. At the studio, workmen built a new steel-and-concrete tank stage, holding 375,000 gallons of water, and in this we launched three 17-ton fishing smacks and a power cruiser for close-range scenes … We began shooting the story March 21, this year; we finished June 18. And then came the scoring and the more or less maddening task of editing the completed picture.“

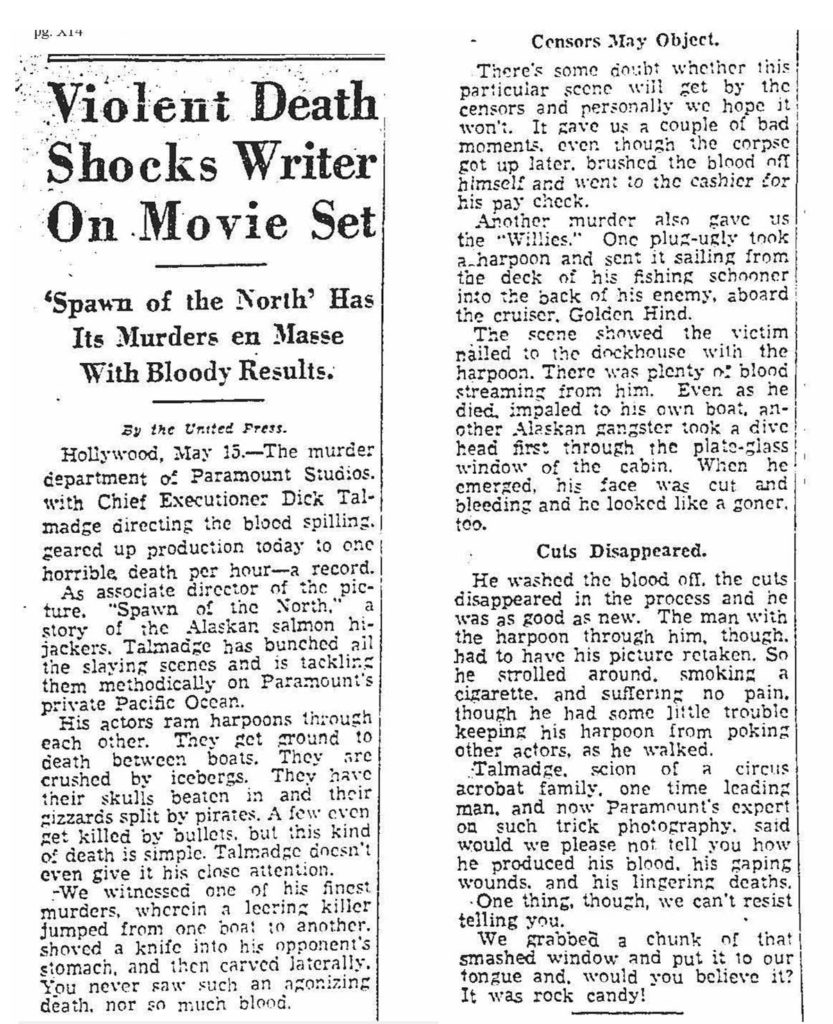

Richard Talmadge’s contributions were featured again in a Washington Post article about the “murder department of Paramount Studios,” describing the filming of the death scenes in the film (“one horrific death per hour — a record”): “Talmadge has bunched all the slaying scenes and is tackling them methodically on Paramount’s private Pacific Ocean. His actors ram harpoons through each other. They get ground to death between boats. They are crushed by icebergs. They have their skulls beaten in and their gizzards split by pirates. A few even get killed by bullets, but this kind of death is simple. Talmadge doesn’t even give it his close attention.”

A New York Times article about master prop man Oscar Lau described the props he acquired for the shoot: “three schooners, an 1870 printing press, the required fish, a bar, and a superb variety of bootjacks and whisky bottles.” (John Barrymore, who played the film’s newspaper publisher, surprised Hathaway with his “startling virtuosity” operating the ancient press — until it was revealed that Barrymore had secretly brought in a professional printer the night before to coach him on its operation.)

Reviews:

The New York Times’ Frank S. Nugent described SPAWN OF THE NORTH as “handwrought for the masculine trade, up to and including the appearance of Dorothy Lamour in a sweater instead of a sarong.”

He notes that the film finds “a surprising store of red meat in the tinned salmon industry” where “scorning such effeminacies as fists or marlin spikes, the picture’s huskies go to it with harpoon guns, sealing knives, lengths of chain and gaffs” and comments that “the bloodshed is beautiful: in technicolor it would have rivaled [Frederic] Remington.”

Despite “the soft finger of romance flicking” at the film’s characters, “romance does not nudge the players too hard or too often” and thereby detract from what Nugent believes to be Hathaway’s main objective: the “creation of a brawling, robustious, 110 per cent male melodrama.”

“R.W.F.” in the Wall Street Journal comments that “probably no picture of recent months has been so action-filled” and that “violent death becomes so commonplace that the last few bits of homicide caused little more than slight gasps from the opening day audience … all in all we counted no less than 20 cases of bloody murder … practically all the minor characters of the picture are liquidated by harpoons, drowning, hatchets, or icebergs.” Even so, it’s “one of the best Paramount releases in a good many months.”

Mae Tinee in the Tribune called it “a worthy and exciting show, its red-blooded fiction tinctured by fascinating information on the fishing industry” before concluding “performances are excellent … the picture is magnificently backgrounded, well directed in the main — and about two reels too long.”

Nelson B. Bell of the Washington Post, on the other hand, simply hasn’t ever seen anything like it:

“If it is action, love, suspense, comedy, gore and thrills you are after in your cinema fare, nothing could more copiously fill the order than Paramount’s production of “Spawn of the North” … in something over three decades of reasonably continuous screen-gazing, I have seen some pretty explosive pictures, but never anything punctuated with such terrific scenes of physical combat and convulsions of nature as the horrendous climaxes of this film story of Northern waters and iron men.”

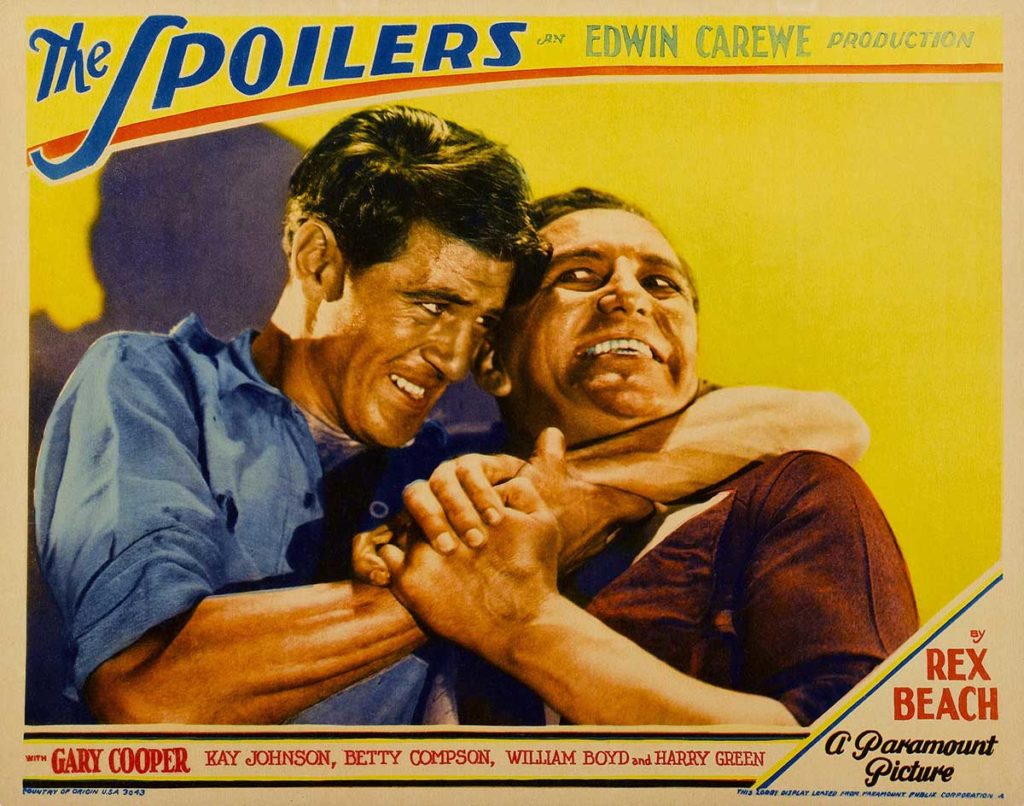

Regarding the fight scenes, Bell claims that the famous fight scene in the 1930 film THE SPOILERS (between Gary Cooper and William Boyd) “seems like a seminary pillow fight in comparison with the skull-cracking and face-gouging that goes on when the advocates of law and order go to bat with the fish poachers.”

Bell notes that by the end of the film, “the Arctic fishing banks are converted from a battlefield into a comparatively safe outlet for legitimate commercial enterprise. It took a tremendous amount of harpoon-fire, gunnery, and marli-spike-swinging to bring this happy consummation about.”

But Bell concludes “it is inevitable that there should be a tremendously solid impact upon the spectator’s consciousness from all this, whether it is a pleasant one, or one of utter revulsion … there will be those, who like strong meat in their motion picture fare, who will insist that ‘Spawn of the North’ is not to be condemned. There will be others who will contend that it is not to be condoned. It is a pretty good picture of its kind — if you like the kind.”

Release:

In what the New York Times described as an example of the “spectacular methods” used by the film industry to launch films with stunts “calculated to garner space in the press,” Paramount decided to give SPAWN OF THE NORTH a double premiere in August 1938: one in Seattle (“the gateway to Alaska”), and the other in Blowing Rock, North Carolina.

Attendees at the Blowing Rock screening were by invitation only, and consisted of 162 people who certified via affidavit that they had never seen a motion picture before. This group of first-timers — who came to the screening “in wagons, trucks, ox-carts, and an occasional automobile” had been found via canvassing the Blue Ridge Mountains surrounding the town.

The New York Times’ Douglas W. Churchill commented: “The reason for the selection of this mountain town is unknown, unless the opinion of one wag may be taken seriously. ‘At least 162 people will testify,’ he said, ‘that this is the greatest motion picture they ever saw.'”

Along similar lines, as part of an effort to “foster warm sentiments along the River Thames” and generally “foster international good-will,” Paramount sent a print of SPAWN OF THE NORTH (“convoyed by an embassy with hat boxes”) to London — primarily because “there wouldn’t have been a ‘Spawn of the North,’ or certainly not one costing over a million, if it weren’t for the inordinate British fondness for tinned salmon — a comestible ranking so high in national esteem that either drenched in vinegar or served up with bill-stickers’ paste will be the pièce de résistance at a million London tables this Sunday night.”

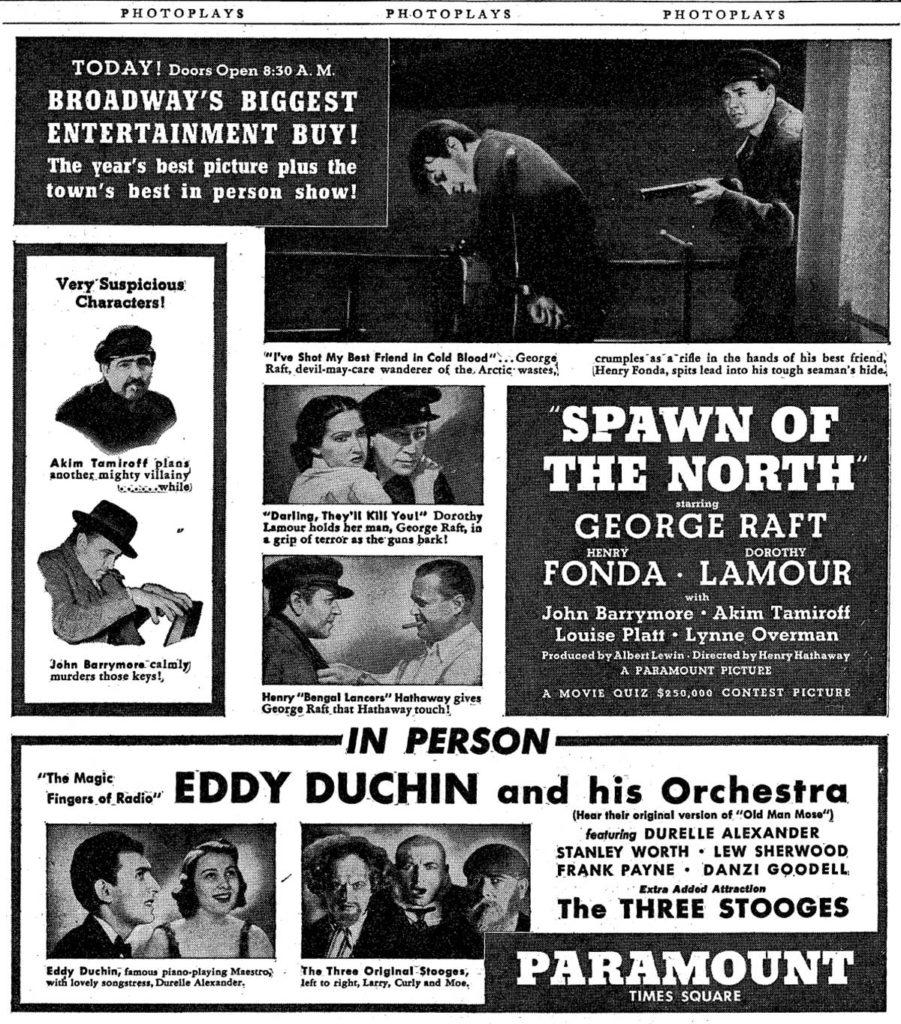

In New York, more conventional screenings started on September 7th at 8:30 a.m. at the Paramount Times Square (capacity around 3,600 seats). Billed as “Broadway’s biggest entertainment buy — the year’s best picture plus the town’s best in person show,” they may have been right about that: in addition to the film, attendees were also entertained by Eddy Duchin (billed as “the magic fingers of radio”) and his orchestra, along with singer Durelle Alexander … plus the original Three Stooges (Larry, Curly, and Moe) in person.

According to the New York Times, SPAWN OF THE NORTH’s opening day set the Paramount’s largest attendance record in six months, with 8,400 people entering the theater before 1 p.m. The film’s run at the Paramount would last around three weeks.

Other films in New York movie houses at that time included Spencer Tracy and Mickey Rooney in BOYS TOWN at the Capitol, Sonia Henie and Richard Greene in MY LUCKY STAR at the Roxy, the Technicolor VALLEY OF THE GIANTS at the Strand, and Robert Taylor in THE CROWD ROARS at Loew’s State.

Frank Capra’s YOU CAN’T TAKE IT WITH YOU was at Radio City Music Hall, but you could also see a production of the live stage play at the Imperial Theater at “sensational reduced prices” — with tickets starting at $0.55, and topping out at $1.10 for the matinee and $1.65 for the evening performances.

About a week after SPAWN OF THE NORTH opened in New York, the film opened in Chicago at the Chicago Theater (around 3,900 seats).

The live stage show at the Chicago included entertainment columnist (and future TV star) Ed Sullivan “entertaining you with intimate gossip about the stars … personalities .. celebrities every day” as part of a Balaban and Katz revue including a long list of now-obscure performers: “Benny Rubin / Lathrope Bros. & Virginia Lee / Ginger Harmon, Jerry Adler” as well as six lindy-hoppers from the Harvest Moon Ball in New York.

(One imagines Sullivan did not enjoy his time in Chicago supporting SPAWN OF THE NORTH. A few months later, he started his column by awarding a “tin statuette” to the film, dubbing it one of the twelve “dullest pictures of 1938,” saying it would be “more instructive” to name the twelve worst films, rather than the ten best, so that “studios would learn what to avoid, rather than what to plagiarize.”)

During SPAWN OF THE NORTH’s run at the Chicago, Chicago moviegoers could have also seen the Marx Brothers in ROOM SERVICE at the RKO Grand (billed as a “world premiere”), SLANDER HOUSE with Adrienne Ames at the State-Lake (ad copy: “WOMEN–being themselves–behind the scenes in the house scandal built–stabbing each other with deadly gossip–telling sensational tales ‘out of school!”), John Barrymore in HOLD THAT CO-ED at the Garrick, and the fourth and final week of Norma Shearer and Tyrone Power in MARIE ANTOINETTE at the United Artists.

Awards:

SPAWN OF THE NORTH received a special Academy Award for “outstanding achievement in creating Special Photographic and Sound Effects.” While not a competitive award, it was arguably the first Academy Award for special effects, and was awarded for the film’s achievements in the following areas: special effects (Gordon Jennings), transparencies (Farciot Edouart), and sound effects (Loren Ryder).

(According to Ryder’s obituary, one of those noteworthy sound effects was the sound of an ice avalanche, produced by recording the squeal of a pig and playing it back backwards. Ryder went on to win four other Oscars, including awards for his roles in developing VistaVision and for pioneering magnetic sound recording for motion pictures.)

Edouart’s Oscar statuette came up for auction in 2012 as part of a large auction of pre-1950 Oscars, and was sold for over $96,000.

Totem Poles (or, that time John Barrymore stole a totem pole):

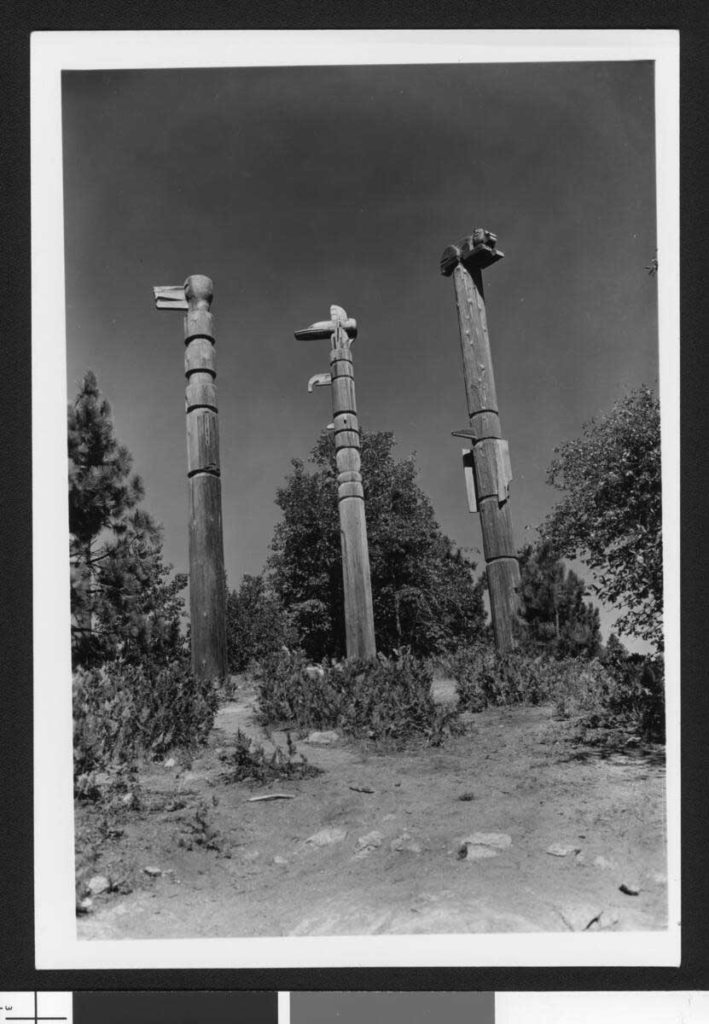

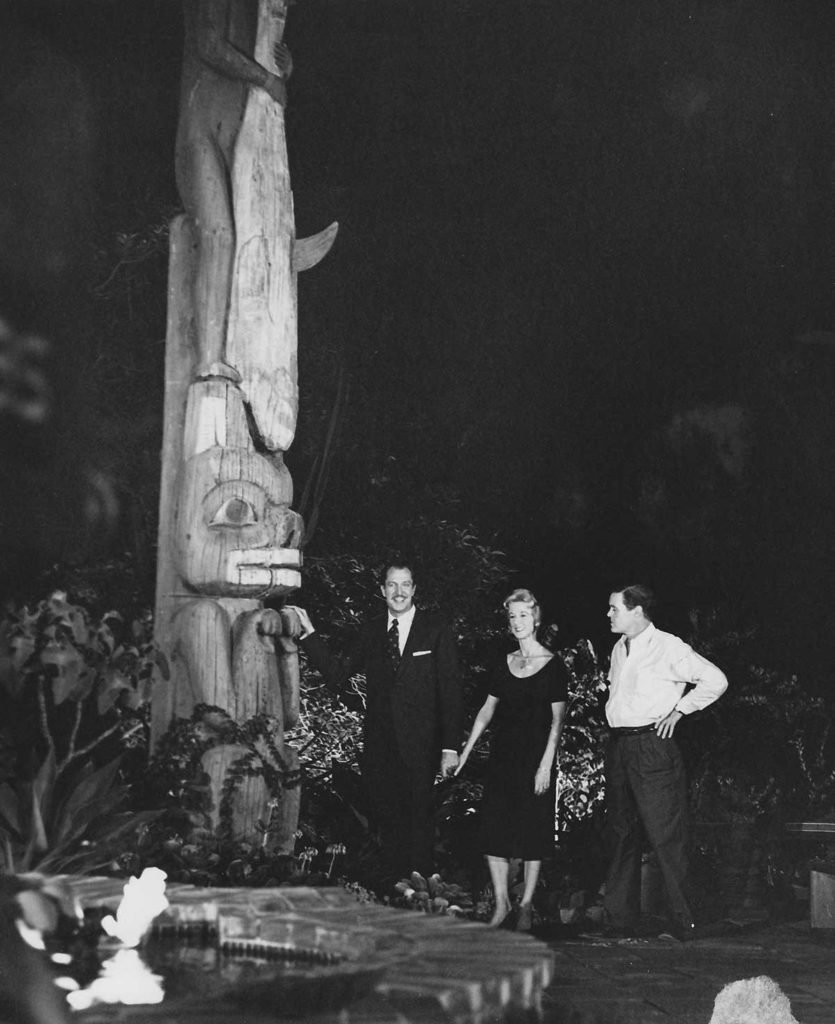

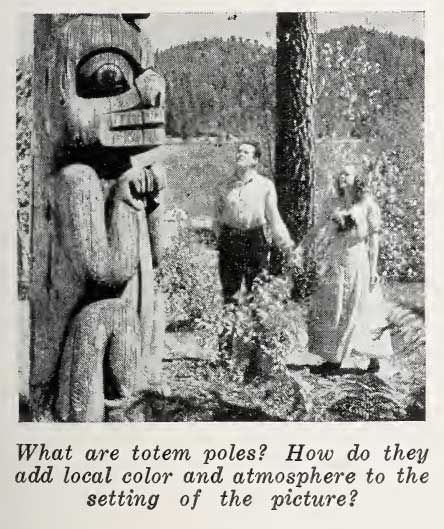

According to a book about the Lake Arrowhead area by Rhea-Frances Tetley, Totem Pole Point (a peninsula in the lake’s Blue Jay Bay) got its name from the five totem poles erected there for the shooting of SPAWN OF THE NORTH. The film’s crew carved the five totem poles on site from logs procured from a local lumberyard.

The totem poles carved for the production remained in place at Lake Arrowhead for decades (at least till the Fifties, and perhaps until the Seventies), and the location and the poles would be used for other films.

Photo of the poles c. 1950:

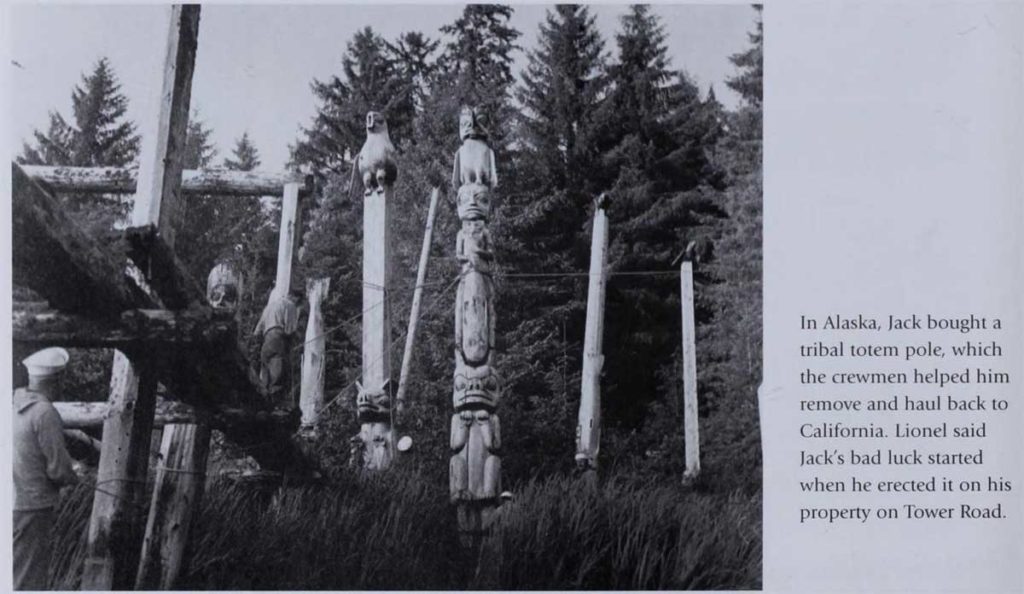

However, one totem pole seen on screen during SPAWN OF THE NORTH was not one of the ones carved by the studio’s craftsmen, nor did it stay there on Totem Pole Point. Articles published at the time indicated that it was rented from John Barrymore, who had brought it back to the States in 1931 after a cruise to Alaska (though there is at least one news story that claims it was instead “lent” to Paramount by the Alaskan Territorial Government).

One fanciful cartoon version of the story suggested that when an additional totem pole was needed on set, Barrymore himself drove the truck transporting the pole from his estate. This seems unlikely, since Paramount actually had some difficulties in retrieving the pole from his home.

According to articles published at the time, Dolores Costello — Barrymore’s former spouse — had obtained an injunction against him after his bankruptcy, which prevented him from removing any property from the house, due to the $160,000 she was still owed in alimony. Even so, she eventually consented to the loan of the item, and the newspapers reported it was taken to Lake Arrowhead for the film. It would return to the Barrymore estate after filming, and — even though Barrymore sold the estate shortly afterwards — the pole would remain there until the 1950s, when Vincent Price acquired it via art collector Ralph Altman.

In 1981, the Prices donated it — rather incongruously — to the Honolulu Museum of Art.

“Brought it back to the States” is an extremely anodyne version of the story of Barrymore’s acquisition, though. Vincent Price recalled in the Fifties that when the pole first appeared in Barrymore’s yard, Barrymore had told him (“with a foxy whisper”) that he had “smuggled it across the border.”

Years later, Price related a more detailed story of Barrymore’s acquisition that he’d heard from Ralph Altman:

“Barrymore had had a yacht and used to take people up to Vancouver and British Columbia, and cruise around the islands. And he came to one island one night and in a village there were all these totem poles in situ. They were burial posts. So Barrymore took a fancy to this one, and asked them if he could buy it. But they wouldn’t sell it, because Mom and Dad were buried in the post. So that night he sent some sailors ashore and they cut it open, threw Mom and Dad in the creek, sawed it in three pieces, and brought it away on the ship with them.”

In 2015, the New Yorker published Paige Williams‘ comprehensive history of the totem pole that John Barrymore had brought back from Alaska, which itself drew on the work of University of Alaska Anchorage anthropologist Steve Langdon.

Langdon had first stumbled across the pole via a “baffling” photo he found in an Alaska archive of Vincent Price posing with it.

Langdon, an expert on the Tlingit people of southeastern Alaska, was able to identify the pole as their work, and — via comparing historic photos — specifically as one that had been located in the village of Tuxecan, on the Prince of Wales Island, one of hundreds that had been there. After thoroughly researching the pole’s provenance, he was eventually able to arrange for the repatriation of the pole to the Tlingit via the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

A little more information about the totem pole:

http://www.thehistoryblog.com/archives/39052

A lecture by Steve Langdon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NrWMzZ_8ndA

and a news story about the repatriation of the totem pole:

http://blog.honoluluacademy.org/museum-hands-totem-pole-to-tlingit-tribe-in-moving-ceremony/

Slicker the Seal:

One member of the cast received seemingly universal praise from reviewers, but the Washington Post’s Nelson B. Bell perhaps did so most thoroughly:

To offset the “Spawn of the North’s” sanguinary drenching, two of the screen’s most competent comedians are given important places in the action. One is Lynne Overman, former Washington stock player; the other is “Slicker.” “Slicker” has all the edge. “Slicker” is a trained seal. But I mean TRAINED. He does practically everything but talk. And, at that, the noises he makes are as intelligible to the casual ear as the Siwash gibberish and Russian jargon that bob up occasionally in the film. “Slicker,” by his work in this picture, takes his place right up there in the front line with Charlie McCarthy and Donald Duck among the cinema’s “freak” artists.

In his second review of the film a few days later, his appreciation of Slicker’s performance hasn’t waned:

A lighter touch of refreshing comedy permeates the piece through the unbelievable precocity of “Slicker,” the trained seal, which, at times, comes dangerously near “stealing the picture” from George Raft, Henry Fonda, Akim Tamiroff, Dorothy Lamour, John Barrymore, Lynne Overman, Louise Platt, and the hosts of others who contribute to its sanguinary content. “Slicker” is quite the chap, endowed with the talents of a composite Johnnie Weissmuller and Eddie Foy. But his human associates are not so bad, either …

The New York Times’ Frank S. Nugent also noted that Henry Hathaway relied on “a gifted trained seal named Slicker for most of his comedy” with the parenthetic aside “Fancy John Barrymore sharing honors with a trained seal!”

Ed Sullivan’s item about the film premiere in Los Angeles’ Westwood Village theater focused primarily on Slicker, too:

“Slicker,” a seal, steals acting honors from George Raft, Henry Fonda, John Barrymore, and Dorothy Lamour at the Westwood Village premiere of “Spawn of the North” … First it was Charlie McCarthy, then it was Snow White, and now Slicker to confound flesh and blood actors.

The program notes had this to say: “Because Miss Lamour is allergic to fish, Slicker had to be doused with Eau de Cologne before doing a scene with the sensitive Miss Lamour.” … The new show business?

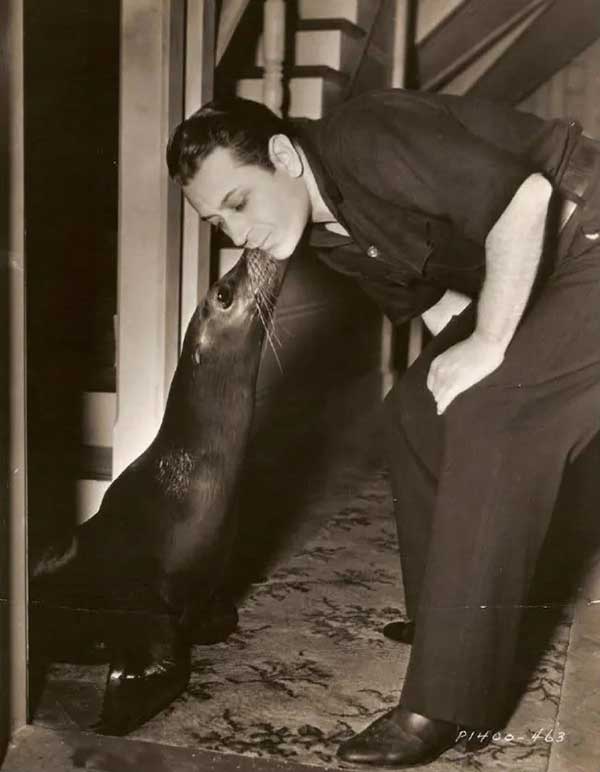

Slicker was a member of a seal troupe owned by Harold W. Winston, who — in the vaudeville days — traveled around the country in two private railcars: one for him, one for his seals. With the decline of vaudeville, he and his seals needed to find alternate employment, and so decamped to Hollywood to appear in films.

More than a decade later, he recalled for the Washington Post where “Slicker” had come from: “Some fisherman off Monterey caught this seal in with a net full of sardines. They turned the seal loose but he followed the boat for three days, so they pulled him back aboard. Slicker learned so fast that he became a Paramount movie star, earning $1500 a week. His best picture was ‘Spawn of the North.'”

A New York Times article from late 1938 dispels some of that Slicker legend, and other movie magic, too:

The legend that seals are affectionate, a theory expounded in “Spawn of the North,” is purely cinematic. They are loyal only to the man with the fish. The truth about the group pinnipedia was unearthed this week on the set of Bobby Breen’s current treatment of filial devotion, “Fisherman’s Wharf,” when Richard A. Parker, who handles Curly and Bill, both of which were seen as Slicker in “Spawn,” discussed the mammals’ screen careers. It seems that any one who knows the cues can work the seals if he has fish to reward them. Because their only incentive is a meal, it is necessary to use two of them, for when one is full of fish he will work no more and his double is substituted.

Parker revealed further that it costs $1 a day to feed each of them, for they eat from ten to fifteen pounds of fish. When they are on location working in the open ocean, it is necessary to put harness on them or they will swim away and never come back. In “Fisherman’s Wharf,” as in “Spawn,” they were retained for the silver screen through the use of piano wire fastened to their harness and the shore.

George Raft getting a kiss from Slicker the seal:

Finally…

A final word from Henry Hathaway, who described the film in an interview with the New York Times’ Bosley Crowther, while he was still in the middle of making it: “It’s a story of a conflict between two brothers over fish … but, gee–I’m beginning to wonder if you can get awfully excited over fish. They’re not worth fighting about, really.”