In advance of our screening of TRUST on June 10th, we exchanged some questions over email with director Hal Hartley about his early films and independent film distribution.

JA: A theme I admire in your films is a respect for people who work with their hands and do technical things. Robert Burke is a mechanic in The Unbelievable Truth, DJ Mendel fixes typewriters in Meanwhile, and Martin Donovan builds computers in Trust. I think that respect comes through in your films, which feel very carefully constructed – no loose screws or defective parts, and honest! Does working on a small budget play into this? Did you have the usual confluence of people breathing down your neck to make the film something you didn’t want it to be? How have you managed to resist the forces of capitalism?

HH: Gradually, through trial and error in my early years of writing and shooting, I began to appreciate the beauty of strong, clean gestures—in dialogue, in physical activity, in shot composition and so on. But I would have worked that way even if I were telling the story of someone totally incompetent—say like Henry Fool. I think the interest in what people do—for a living, certainly, but as a vocation too—this came from my upbringing. My father was a skilled laborer, a structural steel iron worker, as were most of my uncles. All union men. We were raised with a particular work ethic that—without being discussed much (they were not a talkative bunch)—took it for granted that doing one’s job well was the least you could do for your fellow man. As I got more and more into film and reading I gravitated to characters like that and the obstacles they encountered. It seemed to me to be the most relevant thing to make stories about.

One way or the other there are always show biz professionals whose expectations I need to address and, usually, counter. I usually countered by saying I needed half as much money. They would usually acquiesce at that point and I could go do my work in peace.

I’m not sure it’s possible to resist capitalism—or, at least, I haven’t got an option. I’m a commercial producer of non-mainstream entertainment and, as things go, I do okay. But it’s true: I don’t need much. I don’t drive. That seems to be the most significant factor when my family and I compare our relative financial needs. I have a lot more freedom of movement because I don’t have a car, cable TV, or a need for weekend vacations.

JA: There’s not much time between the release of your first feature (The Unbelievable Truth), and Trust. Were you planning both projects at the same time? How did funding come together? If IMDb is to be believed Trust cost about ten times as much as The Unbelievable Truth! Still not a lot though.

HH: Trust cost about nine times more than The Unbelievable Truth—$600,000. The first film was getting some serious festival screenings and was already picked up by Miramax and other foreign distributors when I met Scott Meek of Zenith Productions in London. I was at the London Film Festival. He read the script of Trust in an afternoon and just wanted to know if Adrienne was to be in it. Then we were in business. We made three films together—Trust, Simple Men, and Amateur.

Different versions of Trust existed in the late ’80s. But when I had the chance to make that first feature, I sat down and wrote The Unbelievable Truth the way I did because I knew I could make it for $65,000, which was all we had—it had to be that simple; a few characters, a few locations, the willingness of my extended family to put up with the “circus” again—which is what they called me and my filmmaking friends who would show up in town about once a year to make another of my strange movies. But directing Adrienne Shelly made me rewrite Trust and get it ready in case I had the opportunity to make another film.

JA: Can you talk a bit about working with Michael Spiller on your first several films? Again, the work is very careful and deliberate, and the camera feels very sympathetic to the characters.

Mike and I met at SUNY Purchase. We were classmates and friendly, but did not run with the same crowd. I admired his application to the technical aspects of our training, which were always a trial for me. I was always impatient with machines. Mike loved machines. A car, a camera, a jukebox, a cigarette lighter—machines delighted him. Semester by semester, as I became more obviously a writer and director, Mike became known as a DP. I asked him to shoot my junior year dramatic scene exercise and we became friends. And it just kept going through 1999 when we worked for the last time together on No Such Thing. (He decided to move towards directing TV.) Mike got me over my reticence with machines and showed me—as he himself learned—what a dolly could do, or a dolly and a boom—a dolly and a boom while panning!! And lenses! Exposure! The engineering of shots became my chief joy once something was written.

Trust was shot on an Arri BL. Standard issue 35mm machine back then. Noisy as hell. But solid. Once during Trust I watched as Sarah Cawley, the first AC (who would become my principal DP after Mike) took the camera apart and put it back together again to find out what was causing the noise.

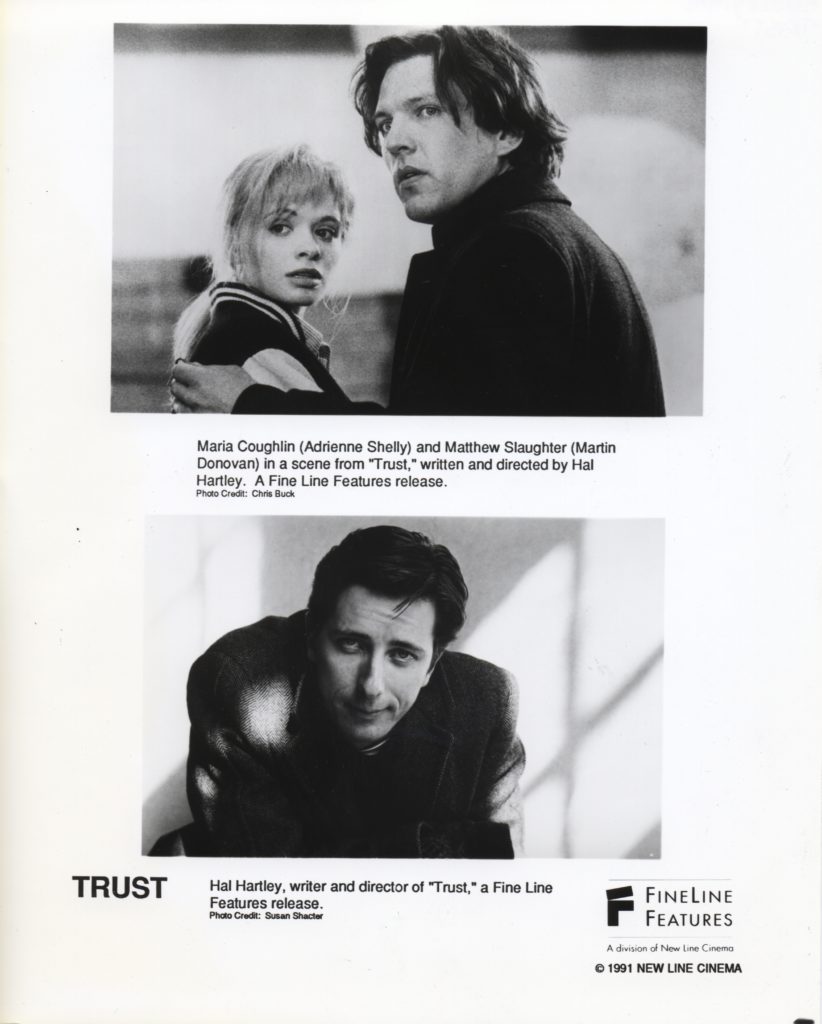

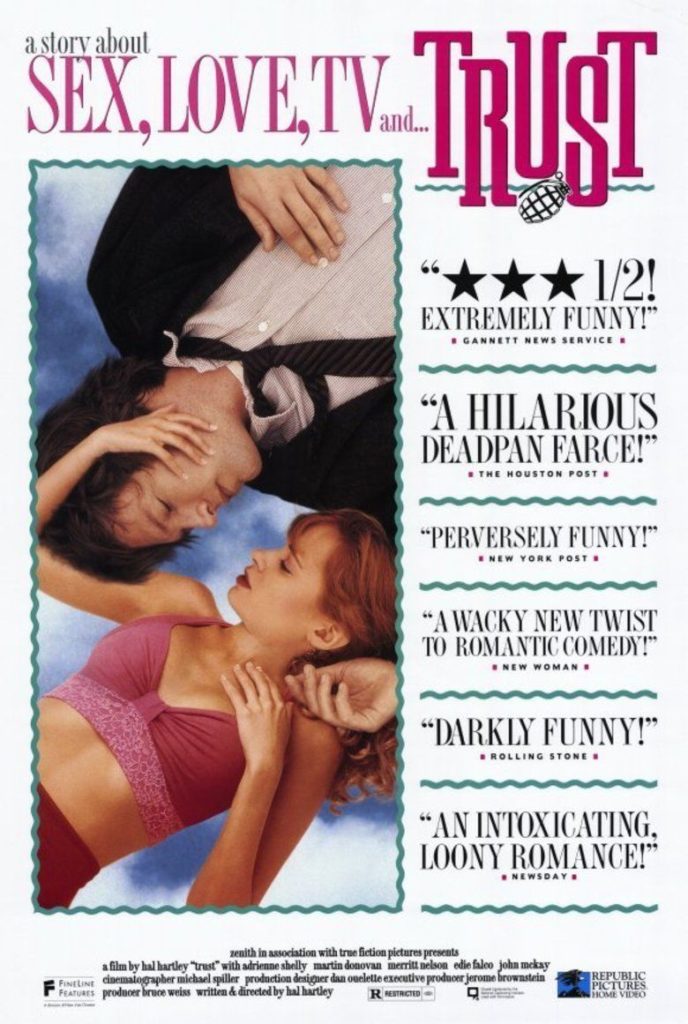

JA: What was the original theatrical release of Trust like? Do you remember how long it screened? What did people make of it? If you look at the US poster, Fine Line Features was marketing it like Pretty Woman or something like that!

I don’t remember. I was busy making Surviving Desire and Simple Men when Trust was released. And I spent most of 1992 in foreign countries promoting all of these films. I wasn’t impressed with any of the distributors. They were dead set on not recognizing what Trust was. They needed it to conform to some norm that had nothing to do with it. They’d ask my opinion about posters or trailers or whatever. I’d say what I’d say and they’d complain I was a naive self indulgent bastard. The American distributor demanded I never refer to Godard or Fassbinder again in interviews. So I just shut up and made the new films. The French distributor did okay, but only because he had a smart publicist who totally got the film and talked the guy into taking it on.

JA: For a while the only thing available on Trust was a PAL DVD, but now you’ve been able to put out these great Blu-Rays and CFS was able to make some beautiful 35mm prints. Can you talk a bit about what the process has been for getting the rights and elements to your films back? Are there any that are still studio owned?

Basically, I’m the only one who has remained in business. And, luckily, I had always negotiated half-ownership of the films. So that put me in a good position to take control of them when everyone else dissolved. But in the US, for Trust, I had to wait for the existing license granted to Republic Pictures, and subsequently bequeathed to Paramount, expired. They had no interest in monetizing it.

Only Fay Grim and No Such Thing are owned and controlled by other companies. But with Fay Grim I’ve been able to gain control over sales on behalf of myself and the owner. I’ll try the same thing with No Such Thing. But it can take years to work through the corporate bureaucracy.

I was paying attention as digital technology and the internet evolved. I know it means different things for different people, but for me globalization means I can manufacture and distribute my work directly to the people who want to see it without the imposition of costly intermediaries. I’ve got a small but sustainable business being a maker of art films.

JA: Did you envision eventually owning the rights to your films and distributing yourself or is this something you’ve become more interested in recently?

No—I didn’t see it coming back in the early days. But I learned that from Spiller: everything we do as filmmakers, no matter how artistic, is through machines. And when I met Kyle Gilman, who would become my editor for many projects, he too trained me to see how everything was becoming computer based—virtual machines. So I’m constantly learning new technologies so that, recently, I can preserve and monetize my old films. It’s wild.

Trust screens on June 10th at the Music Box Theatre in a new 35mm print commissioned by CFS. Click here for tickets.

For more on Hal Hartley, visit www.halhartley.com