The mythos of Jacques Tourneur often begins with his innovative and atmospheric horror film Cat People, the talent fully formed from the very beginning. Of course, when Cat People arrived in 1942, Tourneur was thirty-eight and had been working in movies for the better part of his life. He began as an assistant to his father, the distinguished French director Maurice Tourneur, and subsequently to David O. Selznick. The younger Tourneur directed features in France shortly after the coming of sound, as well as several ‘B’ features in the US before the feline breakthrough. He made some twenty short films between 1936 and 1942, which constitute one of the most underappreciated runs in the annals of American movies.

The mythos of Jacques Tourneur often begins with his innovative and atmospheric horror film Cat People, the talent fully formed from the very beginning. Of course, when Cat People arrived in 1942, Tourneur was thirty-eight and had been working in movies for the better part of his life. He began as an assistant to his father, the distinguished French director Maurice Tourneur, and subsequently to David O. Selznick. The younger Tourneur directed features in France shortly after the coming of sound, as well as several ‘B’ features in the US before the feline breakthrough. He made some twenty short films between 1936 and 1942, which constitute one of the most underappreciated runs in the annals of American movies.

The shorts are not entirely unknown. Chris Fujiawara’s singles out these one- and two-reel M-G-M films on the second page of his critical biography Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall, and goes so far as to cite no less than seven of them as masterpieces. That designation might sound faintly ridiculous when applied to titles like “Killer-Dog” or “What Do You Think? Tupapaoo,” but the challenge in evaluating Tourneur’s shorts ultimately speaks to broader problems in getting a handle on the genre as a whole.

It’s one thing to celebrate short films that premiere in festivals and tour the country in packages, like the annual Oscar shorts programs or the Spike and Mike animation showcases of old, but it’s another thing entirely to elevate the hundreds of shorts that filled out theater programs in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. Upon reviewing a Chuck Jones retrospective offered by the Gene Siskel Film Center in the Chicago Reader, Fred Camper highlighted the basic credibility issue:

On a weekday afternoon in 1972 I visited a fellow film aficionado in his Los Angeles home. Several other people interested in film were also there. Suddenly, at 3 PM, everyone gathered around an old black-and-white television. A longtime auteurist, I wondered what obscure classic was commanding their attention. It turned out to be a daily show of Hollywood cartoons from the 40s and 50s–everyone was trying to guess the directors. I remember thinking, “This is taking auteurism too far.”

It took years for critics and historians to see Bugs Bunny cartoons as the work of Chuck Jones, rather than generic episodes of Looney Tunes or Merrie Melodies with fundamentally corporate authorship. But at least Bugs and Daffy and Foghorn Leghorn and the rest have a sizable fanbase that could be mobilized for deeper study. To date, there is no collection of Tourneur’s shorts on DVD or Blu-ray, no Warner Archive box set dedicated to his efforts. The studio’s manufactured-on-demand label has issued boxes of Vitaphone Varieties and even the infamous Dogville shorts, but Tourneur’s work isn’t so neat.

For one thing, Tourneur flitted between different series, working under the banner of John Nesbitt’s Passing Parade series, the Pete Smith Specialties, the M-G-M Miniatures, the vaguely supernatural What Do You Think? series, and even the Crime Does Not Pay series. Some of these series had a very constricted format, with aw-shucks absurdist observations of Pete Smith dominating the films that bear his name, especially the soundtracks, for which Smith usually read every role. The narrator is omnipresent, to the point where one may easily forget (or deny) that the films were directed in any usual sense. When Tourneur’s shorts are seen at all, they can easily be mistaken for the random filler that Turner Classic Movies slots between features. That several shorts featured the Americanized directing credit of “Jack Tourneur” further suggested the impersonality and compromise of the enterprise.

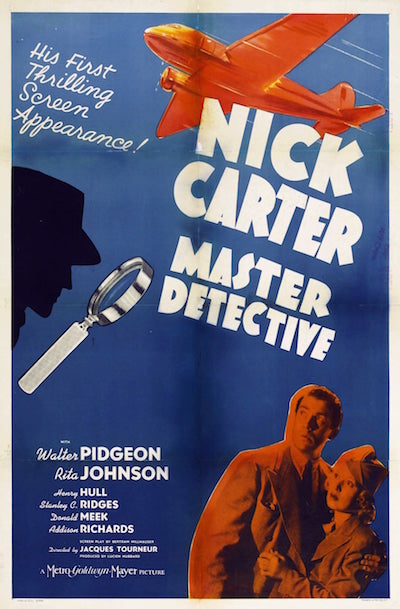

The first time that I had an opportunity to investigate the Tourneur shorts was when I was working at the George Eastman House (now known as the George Eastman Museum) seven years ago. I had been tasked with programming a Tourneur series for GEH’s Dryden Theatre, and I wanted to include a genuine rarity in the lineup. We had preserved Tourneur’s first American feature, Nick Carter, Master Detective, in 35mm, but that ran only an hour. To my surprise, there were six Tourneur shorts on 16mm in the collection. I filed a request to pull them from the vault, and waited.

The first time that I had an opportunity to investigate the Tourneur shorts was when I was working at the George Eastman House (now known as the George Eastman Museum) seven years ago. I had been tasked with programming a Tourneur series for GEH’s Dryden Theatre, and I wanted to include a genuine rarity in the lineup. We had preserved Tourneur’s first American feature, Nick Carter, Master Detective, in 35mm, but that ran only an hour. To my surprise, there were six Tourneur shorts on 16mm in the collection. I filed a request to pull them from the vault, and waited.

Nervous that the shorts would not live up to Fujiwara’s hyperbolic description, I declined to preview the films in the Dryden; instead, I carted the prints down to the basement, stacked them onto a table, and thread them one at a time on a Kodak Pageant in the conference room. The first one that I projected for myself, “Killer Dog” (1936), featured a judge soliciting testimony from a dog–under oath! I could laugh at the scenario, but I couldn’t shake the commitment and professionalism of the execution. As I watched one film and then another, it became clear that the rigid formula of the Specialities and the Passing Parades had focused Tourneur, the ever-present voice-over allowing the apprentice the opportunity to cram more incident and narrative shorthand into each successive project. I kept waiting for a dud, but each short was as good, if not better, than the last: “The Grand Bounce” (1937), “Romance of Radium” (1937), “The Face Behind the Mask” (1938), “The Magic Alphabet” (1942), and “The Incredible Stranger” (1942).

I programmed all six on the same bill with Nick Carter, Master Detective and hoped for the best. We weren’t in the habit of showing shorts at the Dryden (let alone six in one program), so we designated the evening a free member’s movie in hopes of boosting attendance for the show. I needn’t have worried–the variety of shorts, each one different in tone and pacing and setting, thoroughly won over the audience and primed everyone to better appreciate the silk purse Tourneur spun out of the sow’s ear of a bog-standard Nick Carter mystery script. I never felt such a strong sense of audience engagement at the Dryden as I did in the interval between each short.

Subsequent Tourneur retrospectives in Europe have attempted to shed more light on this period. We could occasionally find an opportunity to show an odd short here or there at CFS, such as “The Face Behind the Mask” before Tourneur’s Way of a Gaucho, but that still left a good dozen-plus Tourneur shorts I hadn’t seen. So naturally we jumped at the chance to show a collector’s 16mm print of “Yankee Doodle Goes to Town” before Dodsworth, another tale of an industrialist who could make America proud.

We were looking forward to “Yankee Doodle Goes to Town” anyway, but our curiosity only grew upon taking delivery of the print, which was visibly longer than the 11-minute runtime listed on IMDb and Fujiwara’s Tourneur filmography. (Project films long enough, and you too will be able to guesstimate the runtime of a given reel by glancing at its diameter.) What is this 25-minute version? Was it expanded for the educational and non-theatrical market? Perhaps, but contemporaneous records like 16mm educational film catalogs available through Lantern also list the 11-minute runtime.

We’ll simply present “Yankee Doodle Goes to Town” tonight and hope for a lively discussion afterwards; Tourneur’s shorts rarely disappoint in that department.