What makes a movie?

What makes a movie?

This is a richly theoretical question that’s often been answered by glibly practical guidance. The most common criterion is highly circular: if it’s exhibited in a movie theater, then it’s automatically a movie.

Never mind that there have long been grey areas—misfit media whose very names suggest their dual identities, like ‘made-for-TV movies’ or ‘direct-to-video’ feature films. By dint of their general disreputability, these works were rarely regarded as deep challenges to the established boundaries of cinema. In the 1980s, a number of long works produced for television by established art house directors—Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Dekalog, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, Edgar Reitz’s Heimat—successfully slant rhymed their way to festival success. Treating them as films, rather than TV miniseries, was an honorific gesture, an acknowledgement that their high artistic ambitions automatically marked them as works of cinema. There was no other vocabulary to describe them.

By the conclusion of 2016, these distinctions were lying in shambles, if they ever mattered at all. To talk about the year in moviegoing necessarily requires engaging with this shift. It wasn’t the first year that disruptive new entrants to the film business—Netflix, Amazon, and assorted VOD proponents—sought to change the way we conceive of movies, but it may well be the year they convinced a substantial portion of the public to go along with them.

The year saw countless think pieces proclaiming that movies had been firmly supplanted as the center of popular American culture. The real energy, the driver of the proverbial water cooler conversations in increasingly anachronistic office parks, was peak TV, or perhaps Pokémon Go. The Los Angeles Times even inaugurated a series devoted to the topic: The Blur. Veteran movie reviewers wrote from a defensive crouch; a great new work, like Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann, was first and foremost a refutation of the “death of the movies” narrative.

This debate played out in the cultural blogosphere and on Twitter, but hardly touched the movies theaters themselves—largely because traditional exhibitors were deliberately excluded from the conversation.

• • •

The film business has been always littered with failed theatrical features—projects that once looked like sure bets, but upon completion just don’t merit the expensive advertising campaigns usually required to put over a major theatrical release. No use in throwing good money after bad. If the production costs are low enough, such as the micro-budgeted Blumhouse horror features, forgoing a theatrical release simply means taking a manageable write-down or making up the expense through other revenue streams.

But 2016 saw a host of feature films that were kept from theaters despite festival exposure, strong reviews, or talent with considerable name recognition. These films weren’t withheld from theaters because they were schlock (most of them, anyway), but because their distributors wanted to plant a flag and demonstrate they could dominate the cultural conversation without working through traditional exhibition partners, creating what A.O. Scott derisively described as “platform-agnostic digital entertainment.”

In February, Netflix and the Weinstein Company finally unveiled Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: Sword of Destiny—a long-gestating sequel that was once judged sufficiently prestigious to pose a genuine dilemma to exhibitors who instinctively resist booking titles that are simultaneously available through streaming and VOD platforms. Could these progress-hating fogies really deny audiences a chance to see the follow-up to the highest-grossing foreign film that ever flew through the trees of the American box office? Yes, in fact, they could. Despite the return of Michelle Yeoh, Sword of Destiny was relegated to outlying IMAX hubs in off-brand suburbs. New Yorkers who wanted to see the movie on the big screen had to schlep to Elizabeth, New Jersey; Chicagoans were simply out of luck.

A24, which has attracted a hip, younger clientele to the AARP Art House with creative marketing of titles like Spring Breakers, The Bling Ring, Ex Machina, The Witch, and The Lobster, barely released Gus Van Sant’s Sea of Trees, even though the film screened in competition at Cannes in 2015. True, the reviews were miserable, but surely the combination of Van Sant, Matthew McConaughey, Naomi Watts, and Ken Watanabe could have sold a few tickets. (Someone else apparently thought so, too; a low-budget horror entry, The Forest, set in the “suicide forest” sure to be popularized by Sea of Trees, was released on 2,500 screens while the Cannes entry sat on the shelf, the rip-off appearing long before its probable inspiration.) Sea of Trees never played in Chicago or most other major metropolitan areas, instead receiving a token release (often a single matinee showtime per day) at a slew of suburban theaters to satisfy contractual obligations. On average, most venues brought in $36—or three to four tickets apiece—over the course of the “wide” opening weekend.

But it wasn’t just high-profile films with mediocre reviews that got dumped.

But it wasn’t just high-profile films with mediocre reviews that got dumped.

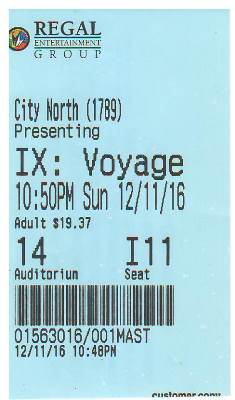

Terrence Malick’s extraordinary documentary Voyage of Time has been in production off and on since the late 1970s. It finally debuted in two versions—a 40-minute IMAX version narrated by Brad Pitt and a 90-minute theatrical version narrated by Cate Blanchett. Neither version played in Chicago, though a third edition—stripped of any voice-over, and cropped to the newly invented aspect ratio 3.6:1—opened without fanfare in December. It played for a week as Voyage of Time: The IMAX Experience in Ultra-Widescreen at Regal City North 14, with a single screening per day. The 10:50 PM showtime was none too hospitable for school children on a field trip or aging Malick partisans hunkered down in the catacombs after Knight of Cups, but so be it. (Another index of how indifferently Voyage of Time was exhibited: I was handed a pair of 3-D glasses for this 2-D show on my way in, which the ticket-taker repeatedly insisted were necessary for whatever-it-is.)

The Little Prince, which attracted strong notices and grossed nearly $100 million abroad, was dropped by its US distributor, Paramount, a week before its release, even though trailers for the film had already been playing for months; the studio handed the movie off to Netflix, which quietly released it with minimal advertising support in a fraction of the theaters that Paramount would have secured. If it ever opened in Chicago, I never found out about it.

Likewise 13th, Ava DuVernay’s acclaimed follow-up to Selma. The documentary opened the New York Film Festival, garnered superlatives from movie critics and criminal justice reform advocates, and secured an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary Feature, but this, too, had only a nominal theatrical release through Netflix. As far as I can tell, its first public screening in Chicago occurred last month at the South Side Community Art Center.

It would be one thing if Netflix and its ilk simply wanted to drive home the idea that movies are obsolete relics of twentieth-century leisure, archaic and outmoded forms that constrain artists working towards a new iteration of media. But Netflix—which doesn’t release figures about how many people are actually streaming its productions—still uses movies as the model and the metric for its new media empire.

Theatrical releases remain a priceless showcase; they’re “events” that still attract near-reflexive press coverage and reviews. That sense of importance—the recognition born through ample free publicity, the veneer of cultural legitimacy, the ineffable movie-ness of the movies—is what distinguishes theatrical releases from straight-to-VOD titles. Netflix subscribers want these familiar things over original content with no public profile. That’s why Netflix will pay a higher price to sublicense theatrically-released films for its streaming service, often in some loose proportion to the number of theaters it commanded at its widest break. Or, as Indiewire explained when dissecting the Sea of Trees release plan, “The 101 theater count is likely no accident. Other indie distributors have a 100-theater minimum release written into their agreements as a requirement for earning carriage on Netflix.”

So, movies are disparaged one moment, and emulated the next. It’s retrograde to give audiences a chance to see a film on the big screen, but it helps the bottom line if the product receives the kind of awards recognition hitherto limited to big screen releases. Oscar recognition makes a movie stand out, gooses international sales, and ultimately extends its saleable life as a catalog title. So Netflix didn’t bother with a good faith theatrical release of The Little Prince, but spared no expense in trying (unsuccessfully) to land the film an Oscar nomination for Best Animated Feature. “Netflix has been spending lavishly on full page newspaper and trade ads, billboards, TV spots,” reported Deadline’s Pete Hammond, “but the coup de grâce is something I have never before seen in any Oscar campaign: The Little Prince actually had its own float in Monday’s Tournament Of Roses Parade!”

The most controversial case was O.J.: Made in America, which preserved a strategic ambiguity since its January 2016 debut at the Sundance Film Festival. Was this 7.5 hour documentary, produced by ESPN Films, a movie or a TV program? It opened in two theaters in New York and Los Angeles before its initial television airing, which technically makes it a movie according to the Academy. It’s told in five 90-minute parts, with fade-outs for commercial breaks, which means its structure and form are dictated by TV’s constraints. Its montage is “cinematic” (a euphemistic way of saying it’s better than TV), but who would sit through it in a single sitting? (The Gene Siskel Film Center screened it over a single Saturday in October, broken up in three parts, and touted it as the Chicago premiere, though it had been available on TV for months.) Ultimately, movie critics and TV critics fought over turf—both wanted to honor O.J. as one of the year’s finest achievements, a vindication of the enduring relevance of their chosen medium.

But let’s be real. If TV were as prestigious as its boosters maintain, then O.J.: Made in America would happily be competing for an Emmy Award, not an Oscar. The fact that its producers and financiers want so much for O.J. to be regarded as a movie demonstrates that the movies are hardly as moribund as we’re told. There’s still an enormous economic incentive for these works to be treated as movies—for the prestige, the awards recognition, and ultimately the durability of licensing deals that still speak the language of the abhorred cinema.

• • •

The theatrical experience is held up as the dividing line between cinema and everything else, even when marshalled for transparently cynical reasons. But what do we leave out when talking about movies with theatrical exhibition as the be-all and end-all?

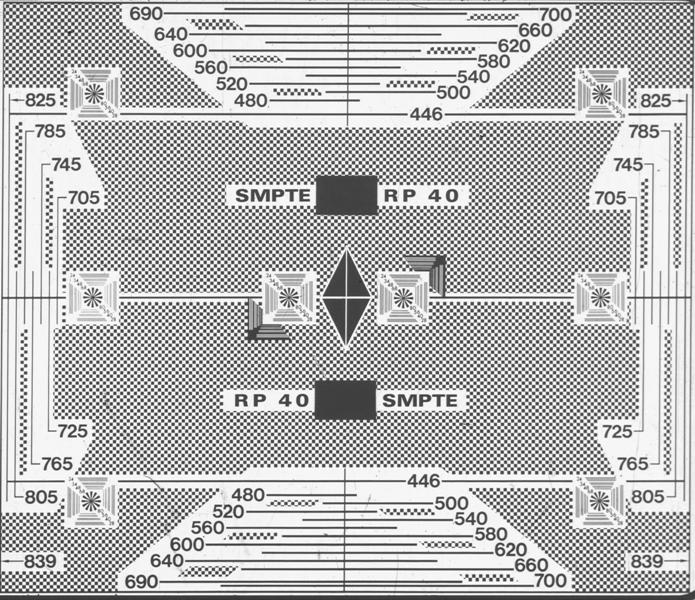

Here at the Film Society, we screen lots of movies that aren’t really movies at all by this rarified definition: educational films intended for the classroom, avant-garde films and experimental animation that never came anywhere near a multiplex, home movies that were never meant to be shown outside the living room. And some of our very favorite films were made for theaters, but never meant to be seen by audiences, like RP-40, the ubiquitous projection calibration designed by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. Should these forms be exiled from discussion because we fetishize the mythic “big screen experience”?

Here at the Film Society, we screen lots of movies that aren’t really movies at all by this rarified definition: educational films intended for the classroom, avant-garde films and experimental animation that never came anywhere near a multiplex, home movies that were never meant to be shown outside the living room. And some of our very favorite films were made for theaters, but never meant to be seen by audiences, like RP-40, the ubiquitous projection calibration designed by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. Should these forms be exiled from discussion because we fetishize the mythic “big screen experience”?

You can’t make a distinction on the basis of the gauge either. Theaters were once the predominant exhibitors of 35mm, but not the only ones. Railroad engineers were once trained with the aid of 35mm simulation films—like a driver’s ed video game simulation, but with a much narrower range of interactivity. We’ve never seen the simulator set-up—presumably it had a brake, as well as some literal bells and whistle—but the footage is plenty illuminating when shown on a conventional projector. It was never intended as cinema, but it grows into the role when projected before an audience. You simply watch a camera strapped to the front of a train as it rolls through the pastures of Canada—it recalls a structural film from the 1970s, or a phantom ride from the turn of the century. The engineer training footage was surely produced in total innocence of this cinematic lineage, and yet it cannot help but evoke it in spite of itself. It was the last thing we ever screened at the Bank of America Cinema in 2010, and the audience loved it.

Or consider another genre with paltry cinematic credentials—the 16mm medical training film. Two weeks ago the Film Studies Center presented one such work, Edward and Naomi Feil’s The Inner World of Aphasia (1968), as part of a series of avant-garde films. It never received any exposure on the big screen, and yet The Inner World of Aphasia boasts the sort of graphically sophisticated fantasy sequences, flashbacks nested within flashbacks, and constantly shifting subjectivities that we expect in an art-house feature. And yet here they are, the form recombined and reoriented in the service of something more practical and earnest. It’s no wonder that The Inner World of Aphasia was recently added to the National Film Registry.

In all of these cases, films that were never intended for the big screen wind up yielding something astonishing when projected in that context. Our perceptions of the work shifts when viewed from a different angle—we’re forced to consider them as movies, with all the deliberate craft and expressive possibilities that implies. A splice is just a splice whether seen in a home movie or a classroom film or a Hollywood melodrama—why should our emotional engagement be any different when the same tools are employed in new contexts?

There was once a comforting degree of expediency and certitude when using theatrical exhibition as the arbiter of which moving images can be anointed as movies. It’s a shaky standard in 2016, with disruptors from all sides trying to dethrone the primacy of theatrical exhibition. If Netflix and its compatriots succeed in defining movies as something more than just whatever happens to be playing at a theater near you, then it only stands to reason that similar amnesty should be granted to all the wonderful works of the past that found cinema where it was least expected.