If you’re at all familiar with our activities at the Chicago Film Society, you probably know that we place special emphasis on the act of projecting motion picture film. At a point in cinema history when digital video has become the exhibition “norm,” we pride ourselves on providing a link to a pre-digital past and a critical framework to contextualize film images. Look at the first page of our program book or click on the About Us section of our web page and you’ll find this paragraph:

If you’re at all familiar with our activities at the Chicago Film Society, you probably know that we place special emphasis on the act of projecting motion picture film. At a point in cinema history when digital video has become the exhibition “norm,” we pride ourselves on providing a link to a pre-digital past and a critical framework to contextualize film images. Look at the first page of our program book or click on the About Us section of our web page and you’ll find this paragraph:

The Chicago Film Society exists to promote the preservation of film in context. Films capture the past uniquely. They hold the stories told by feature films, but also the stories of the industries that produced them, the places where they were exhibited, and the people who watched them. We believe that all of this history–not just of film, but of 20th century industry, labor, recreation, and culture–is more intelligible when it’s grounded in unsimulated experience: seeing a film in a theater, with an audience, and projected from film stock.

The argument that film remains a vital and important exhibition medium into the 21st century, even as cost-cutting measures drive it out of more and more cinemas, often takes a historicist angle that can breed misconceptions about the medium even as it elucidates the importance of the inherent historical memory found in media. Arguments for the value of presenting works of film art in their original media often focus on the ways that analog media can highlight the visual decisions and strategies of the technicians who authored the works. However, we at the Film Society are also interested in the authorship of exhibition, and in understanding the context of media through the marks left on its physical form by various production and exhibition histories.

The act of viewing a film print is NOT a simulacra of past experience. Film stocks, venues, projectors, and audiences have all changed over time, making any attempt at crystallizing a “pure,” historically accurate viewing experience a foolish prospect. Rather than inhibiting the goals of the repertory programmer, this “impurity”–and the historical distance it implies–is of critical importance when it comes to presenting old movies on film. Cultural histories change how we look at the content of media; so too do technological histories. A single screening of a film is just one link in a larger chain of viewing experiences, and the act of watching a film print in the present should stand as paying witness to that historical accretion. Every film print bears the marks of its specific and unique exhibition history, encompassing the wear that arises from its projection, as well as the cultural and technological circumstances surrounding its production.

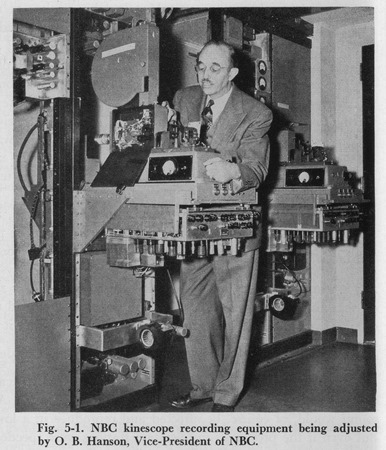

So what to say of the glorious impurity of media hybridity, the migration of moving images forward and backward between the photochemical and electronic, as well as the film objects such migrations have produced? For a good chunk of their twinned histories, televisual and photochemical images have made for strange but not entirely adversarial bedfellows. Electronic moving images have been around since the 1920s but unlike film, what became television didn’t begin as a recording medium at all. Before the introduction of videotape in the mid-1950s, televisual images were recorded and archived (when they were archived at all) using motion picture film. Even after the introduction of magnetic videotape made it easier to archive electronic images, video playback systems were too expensive for a large number of broadcasters to implement, and many television stations relied on film prints for their programming.

The Kinescope provided an early and elegant solution to the ephemerality of the televisual image, but it was also open, as all image making processes are, to being marketed as something more than it really was. A slightly improved version of the Kinescope process yielded a series of “Theatrofilms in Electronovision” in the 1960s, video-film products marketed as “revolutionary” alternatives to live theater or concerts. Predicting the rise of National Theater Live and Fathom Events, these Theatrofilms were usually stage shows, shot on video, perfunctorily edited, and given limited theatrical runs on 35mm. Much like the rise of “alternative content” created expressly for theatrical distribution in the 21st century, there was essentially no epistemological difference between an Electronovision production and any other film projected in a theater, marketing spin notwithstanding. On YouTube, you can find an interview with Richard Burton conducted to promote the release of his Electronovision production of Hamlet, where he touts the process’s “immediacy” while admitting an ignorance of how it actually works. (His excuse, “I’m no scientist,” is an admittedly good one). What is left out in the hoopla of Burton’s Hamlet playing in “1000 theaters live, simultaneously” is that the entire event was essentially a series of coordinated screenings that still involved sending a thousand 35mm prints to a thousand theaters, using the same distribution infrastructure as any other release.

The Kinescope provided an early and elegant solution to the ephemerality of the televisual image, but it was also open, as all image making processes are, to being marketed as something more than it really was. A slightly improved version of the Kinescope process yielded a series of “Theatrofilms in Electronovision” in the 1960s, video-film products marketed as “revolutionary” alternatives to live theater or concerts. Predicting the rise of National Theater Live and Fathom Events, these Theatrofilms were usually stage shows, shot on video, perfunctorily edited, and given limited theatrical runs on 35mm. Much like the rise of “alternative content” created expressly for theatrical distribution in the 21st century, there was essentially no epistemological difference between an Electronovision production and any other film projected in a theater, marketing spin notwithstanding. On YouTube, you can find an interview with Richard Burton conducted to promote the release of his Electronovision production of Hamlet, where he touts the process’s “immediacy” while admitting an ignorance of how it actually works. (His excuse, “I’m no scientist,” is an admittedly good one). What is left out in the hoopla of Burton’s Hamlet playing in “1000 theaters live, simultaneously” is that the entire event was essentially a series of coordinated screenings that still involved sending a thousand 35mm prints to a thousand theaters, using the same distribution infrastructure as any other release.

Electronovision’s wobbly and often blown out video is hard to discern as any sort of aesthetic revolution, but what it lacked in technical refinement it made up for in expediency. Because these Theatrofilms employed the technology and thus the visual grammar of early television, they could be shot and edited at the speed of television. Acclaimed theatrical productions could be seen a mere month after they bowed in their first run while pop music revues like The T.A.M.I. Show (easily the best Electronovision film) could find an audience while the hits they showcased were still on the charts. Still, for all the show of trying to pass off Electronovision as a live phenomenon, Theatrofilms were still just films, made quickly and cheaply with technology that had been around for decades. In 1964, the same projector that would be used to show audiences smeary SECAM footage of Richard Burton in a minimalist Shakespeare production could’ve theoretically also seen My Fair Lady, Nothing But a Man, and Blood and Black Lace run through its gate.

So went the auspicious beginnings of the theatrical exhibition of video images–or rather, the exhibition of images made using video cameras and printed to film. So long as film remained the exhibition standard for moving images, video-to-film blowups were not the odd, counterintuitive objects they appear to be in 2017. If a video artist wanted her images to be projected on a screen of any considerable size without suffering the significant distortion that accompanied primitive video projection, it meant making a film print. In this way, 200 Motels, Parade, and *Corpus Callosum all found their way into theaters of some sort or another, all on 35mm or 16mm film.

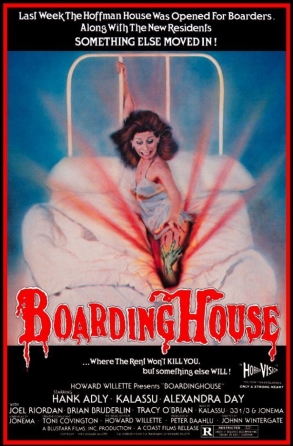

Given the substantial cultural cache of Frank Zappa, Jacques Tati, and Michael Snow, it’s easy to imagine how and why these video-film objects made it onto the big screen. It’s harder to figure out what exactly is going on with Boardinghouse, widely credited as the first horror film to be shot on video and subsequently released on 35mm in 1983. Boardinghouse‘s provenance is weird enough. Written, directed by, and starring Johnima and Kalassu Wintergate, the core members of new age collective and rock band Lightstorm, Boardinghouse is caught between being a vehicle for Johnima and Kalassu’s band, a genre deconstruction that doesn’t scrimp on exploitable qualities like sex and violence, semi-sincere advocacy for meditation and new age spirituality, and particularly garish video art. Like the cycle of DIY shot-on-video trash horror that proliferated in its wake during the video rental heyday of the ’80s and ’90s, Boardinghouse is a particularly crude labor of love, taking advantage of its makers’ familiarity with and access to video production tools, balancing strange and ineffable in-jokes and personal aesthetic proclivities with market-dictated genre elements.

Given the substantial cultural cache of Frank Zappa, Jacques Tati, and Michael Snow, it’s easy to imagine how and why these video-film objects made it onto the big screen. It’s harder to figure out what exactly is going on with Boardinghouse, widely credited as the first horror film to be shot on video and subsequently released on 35mm in 1983. Boardinghouse‘s provenance is weird enough. Written, directed by, and starring Johnima and Kalassu Wintergate, the core members of new age collective and rock band Lightstorm, Boardinghouse is caught between being a vehicle for Johnima and Kalassu’s band, a genre deconstruction that doesn’t scrimp on exploitable qualities like sex and violence, semi-sincere advocacy for meditation and new age spirituality, and particularly garish video art. Like the cycle of DIY shot-on-video trash horror that proliferated in its wake during the video rental heyday of the ’80s and ’90s, Boardinghouse is a particularly crude labor of love, taking advantage of its makers’ familiarity with and access to video production tools, balancing strange and ineffable in-jokes and personal aesthetic proclivities with market-dictated genre elements.

Boardinghouse would also appear just before the home video exploitation market really blossomed, necessitating 35mm theatrical distribution from Coast Films. Boardinghouse may be as weird and wooly as a Kuchar production or early John Waters, but its narrative beats are mostly secondhand horror clichés. It’s a film designed to straddle the twin imperatives of being a personal film and an only marginally disreputable commercial prospect. Were Boardinghouse made a couple of years later, its migration from the realm of the televisual to the photochemical would be unimaginable. Because it arrived at the perfect moment, Boardinghouse managed to mark an interesting crossing of streams–a physical object that saw the passing of one market (the independent exploitation circuit of drive-ins and grindhouse theaters) and the birth of another (the straight-to-video genre revolution).

Boardinghouse is a strange enough text in its own right, but the existence of a 35mm print adds another thread to the film’s already unlikely history. It’s proof that the film was deemed worthy of being screened in theaters at a time when producing prints required a substantial investment of time and money. Today, when the standard for theatrical exhibition media is only marginally higher than media available for the home video market, when consumer grade screening media is regularly employed in art houses and film festivals, when the dominant exhibition format is prized more for its anti-piracy features than its formal advantages, and when open source software exists to freely produce and proliferate so-called professional exhibition media, the act of striking a 35mm print appears to be a much weightier gesture, worthy of only great film art. The unparalleled sumptuousness of the medium has been a big part of the push behind several recent releases notable for their devotion to analog aesthetics such as The Love Witch, Son of Saul, and Inherent Vice. Less reported on are the myriad crass and immediately forgotten studio productions still being distributed on film. How many people in 2016, for instance, made a point of catching a 35mm print of The Angry Birds Movie, a physical object the existence of which seems nearly impossible given the dominant developing narrative of commercial media art in the 21st century?

The fact is, that film prints of both The Angry Birds Movie and Boardinghouse exist. Their existence speaks to the durability of film as a physical medium as well as a technological and cultural institution. The ultimate disposability of video–a condition that stems from its infinite regenerative properties–is muted in its migration to film, its images preserved from the decay endemic to the medium and turned into a physical presence with weight and scale, capable of sharing the same plane with Sunrise, La Règle du jeu, and other noted works of photochemical art.

The fact is, that film prints of both The Angry Birds Movie and Boardinghouse exist. Their existence speaks to the durability of film as a physical medium as well as a technological and cultural institution. The ultimate disposability of video–a condition that stems from its infinite regenerative properties–is muted in its migration to film, its images preserved from the decay endemic to the medium and turned into a physical presence with weight and scale, capable of sharing the same plane with Sunrise, La Règle du jeu, and other noted works of photochemical art.

Film’s material history is littered with bizarre objects like these, bits of misfit media that don’t make a strong showing in repertory programs. Each print, however, answers a specific utilitarian concern and each is imbued with a history particular to its physical being. For us at the Film Society, Bazin’s oft-repeated maxim of all films being created equal holds true in a literal sense. All film prints hold a certain fascination and the ones that distend from fraught media histories can often provide us with the best vantages on the history of moving images. After its essentially forgotten theatrical release, Boardinghouse would go on to find a certain notoriety as a home video product. The argument that one should see Boardinghouse on film because “that’s what its directors intended” or “that’s how people would’ve seen it originally” doesn’t hold up: the Wintergates were vocally disappointed in how the 35mm prints looked and most of the movie’s original audience saw it on video anyway, a format that preserved its original aspect ratio while the hard-matted 35mm print did not. Instead, one should see Boardinghouse on film to marvel at its magnificent impurity, to challenge received notions of medium specificity, and to contribute to its ever-complicated media history. One should watch Boardinghouse on film because the 35mm print exists and because that existence speaks to the strange and circuitous channels through which we receive art.

The Music Box will be presenting 35mm screenings of Boardinghouse at midnight on January 13 and 14, in conjunction with Odd Obsession Movies and the Chicago Film Society. Contra the Wintergates, the 35mm print has great color and looks quite nice overall. Boardinghouse appears courtesy of the American Genre Film Archive. Please see the Music Box website for additional information about tickets and showtimes.