Which version of The Devils are you going to show on Monday?

Which version of The Devils are you going to show on Monday?

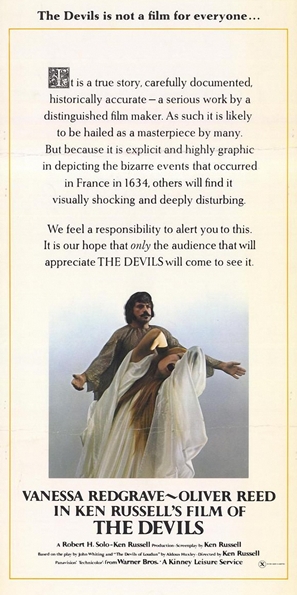

We’ve been asked this question over the phone, in person, and on social media since announcing we’d be screening The Devils at the Music Box. And it’s a perfectly reasonable question, as there are at least four versions The Devils commonly cited: the 111-minute X-rated British theatrical cut; the 108-minute X-rated American theatrical cut; the R-rated American version (either 106 or 109 minutes) released on VHS decades ago; and a spectral cut that re-integrates footage discovered by the critic Mark Kermode.

Adding to the confusion, Warner Bros. prepared a digibeta transfer of The Devils over a decade ago and commissioned several DVD extras but never released a disc—bowing, at least in the imaginations of fevered Ken Russell fans, to a Vatican conspiracy or the resurgent Evangelical stirrings of the Bush era. The studio eventually licensed the transfer and extras to the British Film Institute, which released a Region 2 DVD that runs 107 minutes—but that’s not a new iteration, just a slightly sped-up version of the 111-minute British cut because the video is encoded at the 25 fps PAL standard.

So, which one are we showing?

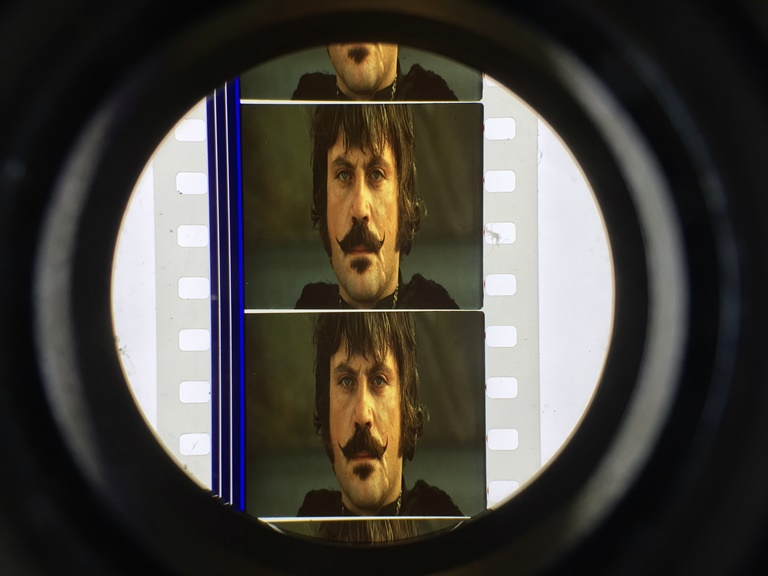

The fact is, film programmers frequently operate in the dark about these matters and have limited means of seeking clarification. The print arrives at the venue a week before the show (at most), and long after calendars have been printed and disseminated.

Programmers rely on distributors, archives, and private collectors to supply film prints for public exhibition. We interface with studio bookers, who almost always have no physical access to the prints they send out. At best, they have notes about the prints, but not always. The prints are usually in another building on the studio lot or located in a storage depot hundreds of miles away, operated by a third-party logistics firm in Sun Valley or Long Island City. To verify the condition of a print, let alone the specific version it represents, bookers can order an inspection from the depot (which costs money and often overstates a print’s deficiencies) or they can rely on scattered remarks from previous venues. Of course, some venues fail to report prints that have been torn in half, while others phone in a detailed assessment of every scratch and speck of dirt (and expect a price adjustment for their trouble). In an era when some studios are eager to junk prints, every condition report is a provocation and potential death sentence.

No matter how many questions you ask, you never quite know what to expect when a courier drops off a print. I once saw a 35mm print of The Departed where the final shoot-out was comically truncated because a cheeky projectionist had removed a few feet of crucial footage: Damon and DiCaprio ride an elevator to the ground floor, door opens, splice, and three people are lying on the floor dead. But sometimes the surprises are pleasant, as when I’ve received studio prints of What’s Up, Doc? and Deliverance that turned out to be vintage IB Technicolor prints. (Had we only known in advance, we could have advertised this fact!)

Borrowing a print from an archive should yield more information in advance of the show, but does not necessarily clarify the details that audiences ask about. An archive will usually inspect a print from first frame to last when it goes out on loan and again when it returns from the venue. They will meticulously document every splice with a footage counter and rate existing damage on internal documents, but it’s a process that values the rote integrity of the object over the content-specific concerns raised by fans. An archive might rate a print of The Devils as excellent because it has no splices or color-fading, even if it’s a bastardized version prepared from a censored internegative.

Borrowing a print from an archive should yield more information in advance of the show, but does not necessarily clarify the details that audiences ask about. An archive will usually inspect a print from first frame to last when it goes out on loan and again when it returns from the venue. They will meticulously document every splice with a footage counter and rate existing damage on internal documents, but it’s a process that values the rote integrity of the object over the content-specific concerns raised by fans. An archive might rate a print of The Devils as excellent because it has no splices or color-fading, even if it’s a bastardized version prepared from a censored internegative.

Home video has fundamentally shifted expectations. The ability to rewind, freeze, and interrogate the image has given rise to fans who claim to know films better than the archivists who restore them. The Toronto International Film Festival prepared a restoration of Shivers under the supervision of David Cronenberg, but it wasn’t until this version was released on Blu-ray by British cult label Arrow Video that fans pointed out it was missing twenty-five seconds of egregious gore that had been censored for the R-rated US version. The hive mind is unparalleled in policing the arcana of split-second mutilations, crotch shots, projectile bile, and assorted depravity memorized from a 1982 VHS release. A professional archivist frankly has bigger fish to fry—like keeping projects on-schedule and under-budget and assuring that the electrical bills are paid and the HVAC system is running properly.

Collectors are a different breed again. As hobbyists, they will devote an extraordinary amount of time to fixing up prints or improving them through non-archival means. One collector friend cannibalized four or five 16mm prints of Run of the Arrow to get a good copy—without the benefit of a Steenbeck or even a footage counter, just eyeballing the optical soundtrack to sync up the footage. But collectors can also be protective towards their prints and extremely forgiving of deficiencies, making them questionable arbiters of quality. “There’s some focus issues, but nothing serious.” “It’s a dupe print, but it’s a good dupe.” (If it had been a bad dupe, you would have already pawned it off on some other collector who likes that sort of thing.) No collector wants to be told that her print has been found wanting, any more than a parent needs to be reminded that his child has a slight lisp. You love them regardless, because to do otherwise would be inconceivable and cruel.

Put it all together, and film programmers are left going to IMDb to verify the running time just like any other schmuck. You can always consult the calendars of other cinematheques or repertory theaters that have played the print before you—but they probably just pulled the pertinent details from IMDb, too. A mere listing is not holy writ. There’s a calendar deadline to meet, and who cares how long the film is? (We think it’s 108 minutes, but maybe we’ll be pleasantly surprised.)

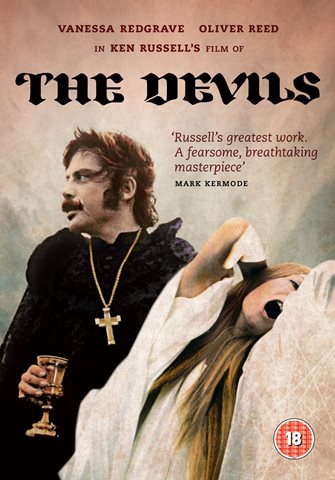

The Northwest Chicago Film Society screens Ken Russell’s The Devils at the Music Box Theatre on Monday, September 26 at 7:00 PM. Tickets are $7. Complete film description available here. Pre-order tickets here.