Like most people who grew up in a town without a dedicated repertory cinema, I couldn’t afford to be picky about movies or the way I watched them. I sought out titles that I read about and didn’t much care how I encountered them for the first time. A first-run movie at the multiplex? Great. A dodgy VHS copy of Hiroshima mon amour (1959) borrowed from the library? Not a problem. Cat People (1942) airing in the 6 AM slot on Turner Classic Movies? Wonderful. GoodFellas (1990) on broadcast television, bleeped left and right and bloated to unimaginable length by commercial interruptions? A terrific movie, even so.

Like most people who grew up in a town without a dedicated repertory cinema, I couldn’t afford to be picky about movies or the way I watched them. I sought out titles that I read about and didn’t much care how I encountered them for the first time. A first-run movie at the multiplex? Great. A dodgy VHS copy of Hiroshima mon amour (1959) borrowed from the library? Not a problem. Cat People (1942) airing in the 6 AM slot on Turner Classic Movies? Wonderful. GoodFellas (1990) on broadcast television, bleeped left and right and bloated to unimaginable length by commercial interruptions? A terrific movie, even so.

It wasn’t until I began college that I met people who approached films a bit differently—people who braved multiple buses to travel across town to see a particular 16mm print or lamented that our city’s sorry iteration of a traveling retrospective had omitted a 35mm print that had definitely been screened on another leg of the North American tour. (You know they’re playing Chicago for dupes, right?) These were people who placed immense value in seeing a film in its original format, and felt closer to the work’s essence on that basis. One friend even used format specificity as a cudgel; whenever he couldn’t settle an argument on a film’s merits, he would ask his interlocutor whether she had seen the title in question projected from 35mm, or only watched it on video. If she’d only done the latter, he would declare himself the winner—he’d seen the print, so his opinion was automatically, axiomatically more valid.

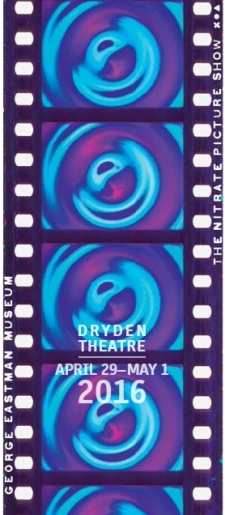

If you think the people described above sound like insufferable hipsters, like the cinephilic equivalent of lanky kids eager to declare “Ahem, I have that on vinyl,” then I’d advise you to stay far, far away from Rochester and its now-annual Nitrate Picture Show, the George Eastman Museum’s three-day celebration of a defunct, flammable film stock that civilians haven’t encountered in seven decades. (Disclosure: I worked for the Eastman Museum from 2010 to 2012, before planning had begun for the inaugural edition of the Nitrate Picture Show in 2015.) Such a festival necessarily invites an escalation of the dynamic described above: “You’ve seen Bicycle Thieves in 35mm, eh? Well, I’ve seen it in nitrate.”

For filmgoers of a certain age, nitrate is an evocative intoxicant, its name an incantation that conjures up living memories of inky blacks, glistening whites, and a greyscale of infinite latitude. Nitrate aficionados will recite their beloved stock’s putative advantages over its safer successors: higher silver content that makes monochrome that much more lustrous, a very clear base that makes the image leap off the screen. Much of nitrate’s mystique rests upon a brand of decidedly subjective, non-empirical aesthetic judgment—you simply have to see the Nitrate Look for yourself.

And make no mistake: the audience that gathered in Rochester was primed for that ecstatic experience. It was a specialized, self-selecting crowd, with a vocal interest in all things photochemical. Between shows, I overheard attendees discussing the Impossible Project and its semi-successful effort to reverse-engineer instamatic Polaroid film. Cell phones were discreetly raised to record video of the Dryden Theatre’s curtain rising. There was an audible gasp and scattered applause in the auditorium when it was announced that a short film would be screened in the short-lived 1.19:1 aspect ratio. If anybody was ready for a nitrate epiphany, it was these pilgrims.

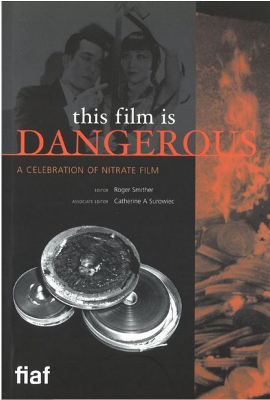

There’s another aspect of nitrate fandom that bears noting, one that has precious little to do with the actual experience of watching the films. Handling nitrate is one of the few genuinely badass activities your average film archivist performs on a regular basis, and so a cheeky death wish cult has arisen around everyone’s favorite film stock. When the Federation of International Film Archives published a near-700-page tome devoted to nitrate, they released it under the only possible title: This Film Is Dangerous. It’s the film archivist’s equivalent to a genteel folk musician’s insistence that “This Machine Kills Fascists.”

There’s another aspect of nitrate fandom that bears noting, one that has precious little to do with the actual experience of watching the films. Handling nitrate is one of the few genuinely badass activities your average film archivist performs on a regular basis, and so a cheeky death wish cult has arisen around everyone’s favorite film stock. When the Federation of International Film Archives published a near-700-page tome devoted to nitrate, they released it under the only possible title: This Film Is Dangerous. It’s the film archivist’s equivalent to a genteel folk musician’s insistence that “This Machine Kills Fascists.”

And so attendees of the Nitrate Picture Show were treated to winking, pre-show safety announcements modeled after an airline evacuation presentation. Passholders also received a commemorative shoulder bag that included a box of matches with the inscription, “Do not strike near nitrate.” (No pyromaniacs interrupted the festival, though I suspect a good many of these charming souvenirs wound up confiscated by befuddled TSA staff at the Greater Rochester International Airport.)

Perhaps the mystique matters more than the films themselves. Like the Telluride Film Festival, the Nitrate Picture Show withholds its line-up until opening day—a choice that nudges the audience towards an unapologetically materialist mindset. There’s some implicit confidence in the festival’s curatorial instincts (and unlike Telluride, God knows no one goes to Rochester for the skiing), but the larger proposition is pretty simple: come and see nitrate film, any nitrate film. All the usual festival attendance considerations drop away (Is the line-up good this year? Will I have another opportunity to see this film elsewhere?) and the prospective pass-holder need only decide whether the chance to experience nitrate is worth so much money and effort, sight unseen. In this year’s edition, the cartoons—Oskar Fischinger’s avant-garde classics Allegretto (1936) and An Optical Poem (1937), as well as Julius Pischewer’s totally unheralded tribute to the Swiss rail system, Cent ans de Chemins de fer suisses (1946)—justified the festival all by themselves within fifteen minutes.

• • •

Once the festivities begin, the Nitrate Picture Show becomes more transparent than most of its peers. Many classics-oriented festivals are somewhat two-faced about print sources: a new restoration from a studio sponsor is loudly touted and prominently attributed, but prints borrowed from private collectors get the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell treatment. For example, the collector-oriented Cinefest confab, which held its final edition last year in Syracuse, always kept the source of its 16mm prints on the down low; the full list was known to four or five people, which meant that most prints were passed from the collectors to the projectionists through a middleman who had to wink, nod, and whisper his way through the lobby.

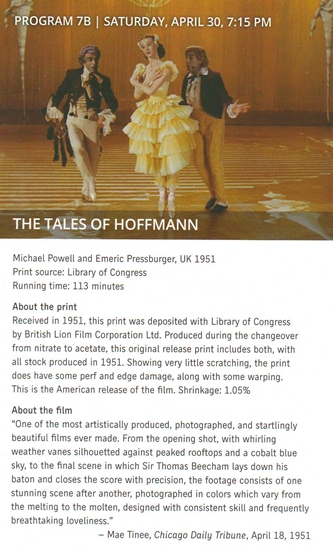

The Nitrate Picture Show program booklet doesn’t just list the source of every print—it also includes its provenance and its latest shrinkage reading. (Nitrate film that has shrunken more than 1.0% is generally considered unsafe to project; remember that a film projector is a precision-engineered machine and consequently, even a modestly shrunken print could be a recipe for a film break, or perhaps a film fire, if its perforations don’t align perfectly with the projector’s sprockets.) The collections management data earns pride of place above the actual film description—and it’s frequently the more involving. (Critic’s quotes can be useful in punching up a film capsule, but I question whether Mae Tinee—who wasn’t even a real person, but the Chicago Tribune’s generic byline for whichever poor newsroom sap wound up with movie-reviewing duty that week—is the most reliable champion of Tales of Hoffmann.)

The Nitrate Picture Show program booklet doesn’t just list the source of every print—it also includes its provenance and its latest shrinkage reading. (Nitrate film that has shrunken more than 1.0% is generally considered unsafe to project; remember that a film projector is a precision-engineered machine and consequently, even a modestly shrunken print could be a recipe for a film break, or perhaps a film fire, if its perforations don’t align perfectly with the projector’s sprockets.) The collections management data earns pride of place above the actual film description—and it’s frequently the more involving. (Critic’s quotes can be useful in punching up a film capsule, but I question whether Mae Tinee—who wasn’t even a real person, but the Chicago Tribune’s generic byline for whichever poor newsroom sap wound up with movie-reviewing duty that week—is the most reliable champion of Tales of Hoffmann.)

The hope of all this, I think, is to foster a fantastically engaged audience. This is a salutary development, and one that other festivals and repertory cinemas should strive to emulate. After all, practically all analog film projection now qualifies as a rare event. When presenting such a specialized offering to the general public, it’s essential that the audience develop some basic understanding and recognition of the undertaking. Conscious consumers of the nitrate brand who are casually conversant in basic archival terminology are necessary for building up and sustaining the Nitrate Picture Show over the long term.

There are several passages in the Nitrate Picture Show program book that ask the audience to make that leap, to put on their slightly stained archivist hats and evaluate films in a way that runs contrary to their everyday experience. The most notable is generally applicable to all analog film presentations, not just nitrate: “On display is the visual texture and resonance of the prints themselves in all their splendor—and, yes, with the blemishes and flaws they accumulate over time. All of this is part of the nitrate experience.”

In an exhibition landscape where most every repertory screening is touted as the latest 2K or 4K restoration, we need to give audiences the terms to describe and appreciate an alternative. Otherwise, we may as well consign every archive’s decades-in-the-making collection of exhibition prints to the rubbish pile. There’s a difference, of course, between honestly acknowledging the natural wear and tear that accumulates on a print and appropriating any scratchy, splicey, faded-to-pink print as an emblem of the authentic grindhouse experience. The audience deserves the vocabulary to recognize that difference.

• • •

So, is nitrate worth all the trouble, the expense, and the non-trivial risk? To judge by the size and enthusiasm of the audience at the Nitrate Picture Show, the answer is a resounding yes. Anything that motivates hundreds of people to go to the theater for a film screening should be commended. And the emotional component of making a trek to see nitrate shouldn’t be discounted, either. One of the highlights of the Nitrate Picture Show was George Willeman’s introduction to Tales of Hoffmann (1951), wherein he confessed that he’d never had an opportunity to see nitrate projected before, even though he’d been handling nitrate on a daily basis at the Library of Congress for more than three decades. Who can argue with that?

I’ve been privileged to project my fair share of nitrate prints, and I’ve seen a handful of others as an audience member at the Dryden and elsewhere. I saw my first nitrate print, Night Unto Night (1949), when I was a programming intern at UCLA Film & Television Archive in 2005 during a Don Siegel retrospective. The fact that the Archive would be screening a nitrate print was noted on the calendar, but otherwise did not receive much fanfare. Internally, I was simply instructed to mark the show report with a prominent “N” amidst a cluster of stars to remind the projectionist that he’d be handling nitrate that afternoon.

I’ve been privileged to project my fair share of nitrate prints, and I’ve seen a handful of others as an audience member at the Dryden and elsewhere. I saw my first nitrate print, Night Unto Night (1949), when I was a programming intern at UCLA Film & Television Archive in 2005 during a Don Siegel retrospective. The fact that the Archive would be screening a nitrate print was noted on the calendar, but otherwise did not receive much fanfare. Internally, I was simply instructed to mark the show report with a prominent “N” amidst a cluster of stars to remind the projectionist that he’d be handling nitrate that afternoon.

The Dryden’s programmer, Jurij Meden, alluded to a similarly nonchalant attitude when introducing Bicycle Thieves (1948) at the Nitrate Picture Show. Before this nitrate copy was deemed worthy of a pilgrimage, it was just another print in the collection—one that had once been publically screened at least fifteen times over a decade according to department records. How does a common object survive being elevated to such a pedestal?

Personally, I’ve never found there to be an appreciable difference between nitrate and safety stock on screen. Are some nitrate prints exceedingly beautiful? Yes, of course, but so too are many safety prints. The Eastman Museum holds a 35mm acetate print of Possessed (1931), printed direct from the original camera negative (OCN), that is as luminous as anything that was screened during the Nitrate Picture Show. It so happens that many nitrate prints were also printed direct from the OCN—and that proximity to the original source likely matters as much as the nitrate base itself. Most any copy competently manufactured directly from the OCN would be exceptional, even if it were printed on onion skin.

The prints of Road House (1948) and Enamorada (1946) screened at this year’s Nitrate Picture Show were very good, but not necessarily better than the modern 35mm polyester copies of these titles that I had seen some years ago. This is as it should be: I’d rather live in a world where archivists and lab technicians can get very, very close to approximating the look of an original nitrate release print instead of one where everybody is constantly lamenting the unattainable perfection of past glories. It might even be instructive to present side-by-side comparisons in future editions of the Nitrate Picture Show; I suspect that the nitrate converts would retain their convictions, the skeptics would remain on the fence, but everyone would walk away even more engaged.

The Nitrate Picture Show’s finale, the “Blind Date with Nitrate,” surely silenced any doubters. The title wasn’t revealed until the first frame hit the screen—in German, no less. It was a real conceptual holy grail: a silent film, projected from an 88-year-old nitrate print with unannounced piano accompaniment from Philip Carli. The title was Edwin Carewe’s Ramona (1928), a film that was presumed lost until only a few years ago and remembered mostly for the staggering volume of sheet music it sold in its day. The Library of Congress restored this film from a repatriated Czech print and toured their new 35mm print around in 2014. The restoration left something to be desired, but who could be picky given the obvious limitations of the surviving material? Who could have contemplated that another 35mm print—a German distribution copy seized from the Reichsfilmarchiv by the Soviets as a war trophy in 1945 and deposited at Gosfilmofond—had survived intact?

The Nitrate Picture Show’s finale, the “Blind Date with Nitrate,” surely silenced any doubters. The title wasn’t revealed until the first frame hit the screen—in German, no less. It was a real conceptual holy grail: a silent film, projected from an 88-year-old nitrate print with unannounced piano accompaniment from Philip Carli. The title was Edwin Carewe’s Ramona (1928), a film that was presumed lost until only a few years ago and remembered mostly for the staggering volume of sheet music it sold in its day. The Library of Congress restored this film from a repatriated Czech print and toured their new 35mm print around in 2014. The restoration left something to be desired, but who could be picky given the obvious limitations of the surviving material? Who could have contemplated that another 35mm print—a German distribution copy seized from the Reichsfilmarchiv by the Soviets as a war trophy in 1945 and deposited at Gosfilmofond—had survived intact?

To be candid, I was audibly exasperated when Ramona came on screen. I had already seen the film in the LoC print and found it to be lovely but leaden—how could I sit through it again? But seeing Ramona in nitrate proved an altogether different experience. For one thing, the Gosfilmofond nitrate is tinted, while the LoC copy is black and white. The tinting scheme isn’t anything complicated—blue for night, red for fire, amber for daytime interiors, etc.—but it carries the weight of authenticity. Most every silent film that we see in 2016 has had its colors reproduced or recreated in some fashion, whether through color internegative, color injection (flashing the negative), modern dye baths, or video tinting. All of these methods are more accurate and pleasing than a straight black-and-white copy, but they rarely capture the subtle, delicate palette that original audiences actually saw. The Gosfilmofond nitrate also looked perhaps a half-stop over-exposed, with no true blacks in sight; in combination with the pastel tints, the print possessed an ethereal quality that presented Carewe’s pictorialism at its best advantage. The visual plan that had peeked through intermittently in the Czech print emerged in full force in the Gosfilmofond nitrate. It was simply a new movie—elegant, expertly staged, reverent towards its source material but never stiff.

Maybe this film is dangerous after all.

—-

Cross-posted with the San Francisco Silent Film Festival