Before tonight’s screening of Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice, we’ll be presenting a rare short: Doom Town. Call it a prelude or a grim appetizer to Tarkovsky’s vision of the apocalypse, but Doom Town is so compelling in its own right that it deserves a few words. Originally released in polarized 3-D, Doom Town will be screened in 2-D, in a print made directly from one of Doom Town’s original camera negatives.

Before tonight’s screening of Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice, we’ll be presenting a rare short: Doom Town. Call it a prelude or a grim appetizer to Tarkovsky’s vision of the apocalypse, but Doom Town is so compelling in its own right that it deserves a few words. Originally released in polarized 3-D, Doom Town will be screened in 2-D, in a print made directly from one of Doom Town’s original camera negatives.

Whenever I try to explain the Film Society’s interest in physical media to a mixed audience, I shamelessly shoplift from other disciplines. Approach film prints like an anthropologist, I suggest. Who made them? Who used them? What do the print’s material characteristics suggest about its origins and purpose?

When looking at a 35mm print, these answers are often, but not always, pretty straightforward. A 35mm print is most likely a feature film or a short, produced by professionals who believed their project had some sizable commercial value. They worked from the assumption that theater owners would recognize that potential and book the film in a first-run cinema. A 16mm print, by contrast, can’t be pinned down so easily: its sites of exhibition could have ranged from a hospital or a church to a school or private home. Producers of 16mm films wanted to recoup expenses, but the profit motive was not always paramount: it might be more important to educate, agitate, or organize the audience.

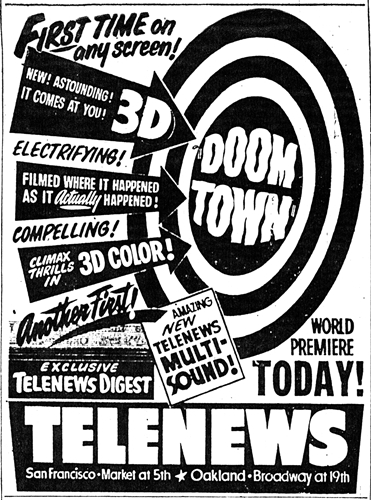

Occasionally, though, a film confounds these parameters. One such unaccountable object is Doom Town, a 35mm pseudo-newsreel with a definite political axe to grind, masquerading none-too-convincingly as a piece of theatrical ballyhoo—in 3-D, no less. It follows an unnamed journalist covering an atomic detonation staged for a compliantly stenographic press corps in Nevada’s Yucca Flats. In 1953, the film would have been understood and received as a documentary, when that term more comfortably encompassed recreations and dramatizations of contemporary issues. Indeed, it was briefly promoted as the first 3-D documentary. Moment to moment, Doom Town could also be described as a film noir with the tart-tongued, factual veneer of Call Northside 777, an atrocity reel that plays to the cheap seats, an anti-travelogue skewering the cultural wasteland of Las Vegas, and a work of high-flown, occasionally pretentious poetry. Is it working against itself—or against us?

Occasionally, though, a film confounds these parameters. One such unaccountable object is Doom Town, a 35mm pseudo-newsreel with a definite political axe to grind, masquerading none-too-convincingly as a piece of theatrical ballyhoo—in 3-D, no less. It follows an unnamed journalist covering an atomic detonation staged for a compliantly stenographic press corps in Nevada’s Yucca Flats. In 1953, the film would have been understood and received as a documentary, when that term more comfortably encompassed recreations and dramatizations of contemporary issues. Indeed, it was briefly promoted as the first 3-D documentary. Moment to moment, Doom Town could also be described as a film noir with the tart-tongued, factual veneer of Call Northside 777, an atrocity reel that plays to the cheap seats, an anti-travelogue skewering the cultural wasteland of Las Vegas, and a work of high-flown, occasionally pretentious poetry. Is it working against itself—or against us?

The independently-produced Doom Town played as a short subject with the Los Angeles run of William Cameron Menzies’s The Maze, and took two more bookings at newsreel theaters in San Francisco and Oakland before disappearing for more than three decades. Can the film’s withering anti-nuke stance account for its apparent suppression? Perhaps, but can Doom Town even see itself in the mirror? A downbeat counterpoint to optimistic declarations from military brass, such as the howler that “with proper equipment and procedures, casualties resulting from an atomic bomb can be considerably limited,” Doom Town is hardly light entertainment. The notion that this film could ever share space on a theater bill, innocuously slotted between a musical revue and cartoon, is witlessly absurd and entrancingly naïve. You stare at the film and wonder where the money came from, and who thought this dusty pill would go down more easily in 3-D.

A decade before Dr. Strangelove and Fail Safe, Doom Town suggests that the political and defense establishment is fundamentally averse to grappling with the consequences of its brinkmanship. A military spox at Desert Rock Base even spins nuclear war as a boon for the lowly enlisted man: “Don’t let anyone delude you about so-called ‘push button war,’ with its guided missiles and long-range bombers. The role of the foot soldier is more important than ever. Bayonets and hand grenades will still be necessary—to dig out the enemy.” Such prognostications are frequently undercut by the narrator’s faux-hardboiled deadpan-isms (“Leave it to the army and the Atomic Energy Commission to pick nice weather for their atomic picnic”)—and, of course, by Doom Town’s throat-seizing climax, a blast rendered in sickly color.

It’s crucial to remember the fringe that the anti-nuclear posture occupied in the Red-baiting atmosphere of 1953, the year that Manhattan Project scientist and M.A.D. skeptic J. Robert Oppenheimer was marginalized and stripped of his security clearance. Doom Town is no Duck and Cover, cheerfully advising viewers on the finer points of surviving a nuclear exchange. If anything, it’s closer to the cautionary left-wing folk songs like Vern Partlow’s “Old Man Atom” and Charter Records chestnuts like Sir Lancelot’s “Atomic Energy”—tunes that delight in wordplay that blasphemes the body politic (“… all men may be cremated equal”). Or perhaps Doom Town’s true blood brother is “The Great Atomic Power,” the Louvin Brothers’ 1952 rapture-ready gospel classic, with its memorable refrain “Are you ready for the great atomic power? / Will you rise and meet your savior in the air?” The concluding narration of Doom Town would be much at home in a mainline Protestant sermon, gently reminding parishioners of their mortal limitations and earthly fallibility:

It’s crucial to remember the fringe that the anti-nuclear posture occupied in the Red-baiting atmosphere of 1953, the year that Manhattan Project scientist and M.A.D. skeptic J. Robert Oppenheimer was marginalized and stripped of his security clearance. Doom Town is no Duck and Cover, cheerfully advising viewers on the finer points of surviving a nuclear exchange. If anything, it’s closer to the cautionary left-wing folk songs like Vern Partlow’s “Old Man Atom” and Charter Records chestnuts like Sir Lancelot’s “Atomic Energy”—tunes that delight in wordplay that blasphemes the body politic (“… all men may be cremated equal”). Or perhaps Doom Town’s true blood brother is “The Great Atomic Power,” the Louvin Brothers’ 1952 rapture-ready gospel classic, with its memorable refrain “Are you ready for the great atomic power? / Will you rise and meet your savior in the air?” The concluding narration of Doom Town would be much at home in a mainline Protestant sermon, gently reminding parishioners of their mortal limitations and earthly fallibility:

I saw it and reported it, and I almost didn’t believe it. But I do. Man has built himself many monuments—pyramids, great walls, huge dams, atom bombs. But no man has yet come up with the plans to make a blade of grass.

As a film, Doom Town might be productively bracketed with two other 1953 documentaries that bend and profane the form: Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, and Ghislain Cloquet’s Les statutes meurent aussi and Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda? Each is a plea for radical candor, a jeremiad against nicety. All three angrily dismantle the subjects they’re meant to chronicle, turning stock footage and art objects against the dominant culture that produced them. And this unholy trinity points toward the potential of the essay film, a new form of documentary unmoored from the genre’s ethnographic and educational roots.

Due to its aborted release, Doom Town persisted largely as a rumor. (Even today, it’s a no-show on IMDB.) We are exceedingly fortunate that Doom Town survives at all, though the version we see today may or may not match the original.

“There were unsubstantiated reports of a 3-D atomic bomb short for years but nobody had any proof or documentation,” recalls Bob Furmanek, of the 3-D Film Archive. “I was doing work for Jerry Lewis in 1985 and found it in a vault of orphaned film elements in Hollywood. That was the same vault where I found Stardust in Your Eyes and the prologue short to Bwana Devil. The negatives were slated for destruction and had I not been in the right place at the right time, the film would not exist today.”

“There were unsubstantiated reports of a 3-D atomic bomb short for years but nobody had any proof or documentation,” recalls Bob Furmanek, of the 3-D Film Archive. “I was doing work for Jerry Lewis in 1985 and found it in a vault of orphaned film elements in Hollywood. That was the same vault where I found Stardust in Your Eyes and the prologue short to Bwana Devil. The negatives were slated for destruction and had I not been in the right place at the right time, the film would not exist today.”

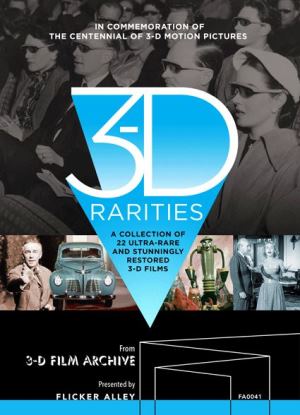

“The third reel with the color footage was not there (probably used for stock shots after the film was shelved in 1953) so Peter Kuran recreated the sequence using actual 3-D atomic footage that he found. Who knows, some of it might have originally been in Doom Town!” The 3-D Film Archive, which generously loaned a 35mm print for our screening, has also issued the film in its full stereoscopic glory on Flicker Alley’s 3-D Rarities Blu-ray set. Seen in 2-D or 3-D, Doom Town wipes out everything for miles around.

Doom Town (1953)

Production Company: 3-D Productions. Director of Photography: Alan Stensvold. Editor: Jerry Young. Music: Paul Dunlap. Writer: Gerald Schnitzer. Producers: Berman Swarttz & Lee Savin. Director: Allen Miner

All images courtesy of the 3-D Film Archive.