It’s not fair, the journalist reminds us, to pick apart and censure his headlines; the reporting is his work, but the boldface entrée is not. Case in point: Randy Kennedy’s informative dispatch on the state of the Andy Warhol film collection in last Thursday’s New York Times was saddled with a most unfortunate headline: “Digitizing Warhol’s Film Trove to Save It”—a premise that’s both wrong and not quite argued in the piece itself.

It’s not fair, the journalist reminds us, to pick apart and censure his headlines; the reporting is his work, but the boldface entrée is not. Case in point: Randy Kennedy’s informative dispatch on the state of the Andy Warhol film collection in last Thursday’s New York Times was saddled with a most unfortunate headline: “Digitizing Warhol’s Film Trove to Save It”—a premise that’s both wrong and not quite argued in the piece itself.

The gist of the article is simple enough: the archive of Andy Warhol’s prolific, prodigious film work—owned by the Warhol Museum, but stored and conserved at the Museum of Modern Art—has finally been slated for digitization. The scope of the collection is daunting; per the Times, only a tenth of Warhol’s surviving film work is available through MoMA in circulating 16mm prints. And even those can scarcely be said to be available because “[f]ewer and fewer people have the ability to show 16 millimeter,” according to Warhol Museum deputy director Patrick Moore. “I think the art world in particular, and hopefully the culture as a whole, will come to feel the way we do,” Moore adds, “which is that the films are every bit as significant and revolutionary as Warhol’s paintings.”

I agree with Moore’s assessment of the stature of Warhol’s film output, but not its inaccessibility. Writing about this corpus six years ago in collaboration with my colleague Becca Hall, we observed:

Each new film expands one’s sense of the challenge that Warhol posed to cinema, working out forms that resurrect the legitimacy of the earliest cinema devices and simultaneously point toward its future. A supposed minimalist, Warhol created movies so bereft of the aesthetic excesses of his peers that one observer once remarked without irony that one of his films resorted to “such unWarholian elements as color, sound, editing, and camera movements.”

Warhol’s films are minimalist, insofar as they pause and linger over the innate characteristics of cinema that others see as a means rather than an end — light and texture, movement and stasis, figure and frame — and force us to engage them anew. On the rare occasion that these elements are harnessed for narrative purposes they still maintain a forceful interest as autonomous qualities. Warhol’s film are about looking (and eventually listening) and reclaiming such frequently passive acts as staggering, ecstatic experiences.

The occasion? A fifteen-film series that we programmed for Doc Films at the University of Chicago in 2008, with all titles shown from 16mm prints. In 2007, Facets Cinematheque presented sixteen Warhol films, also in 16mm, with minimal overlap between the two series. And over the last two decades, Patrick Friel has managed to screen most every new Warhol restoration in 16mm through Chicago Filmmakers or White Light Cinema. In the last ten years, I’ve also caught 16mm projections of Warhol films at the Hyde Park Art Center (Kiss) and the University of Chicago Film Studies Center (My Hustler). Doc Films habitually presents a Warhol or two every summer; in fact, Vinyl screens this Wednesday in 16mm.

The occasion? A fifteen-film series that we programmed for Doc Films at the University of Chicago in 2008, with all titles shown from 16mm prints. In 2007, Facets Cinematheque presented sixteen Warhol films, also in 16mm, with minimal overlap between the two series. And over the last two decades, Patrick Friel has managed to screen most every new Warhol restoration in 16mm through Chicago Filmmakers or White Light Cinema. In the last ten years, I’ve also caught 16mm projections of Warhol films at the Hyde Park Art Center (Kiss) and the University of Chicago Film Studies Center (My Hustler). Doc Films habitually presents a Warhol or two every summer; in fact, Vinyl screens this Wednesday in 16mm.

Outside of Chicago, major Warhol film retrospectives have been held in New York in 1988, 1994, 2007, and 2009. Los Angeles saw at least twenty titles in conjunction with a Museum of Contemporary Art exhibition in 2002. The Warhol films were genuinely out-of-circulation and unviewable (at the artist’s request) from 1972 to 1987, but they’ve been consistently available from MoMA for the last quarter-century and many venues have taken advantage of that bounty. (A good overview of the 16mm exhibition landscape can be glimpsed in the exhibitor directory maintained by the good folks at 40 Frames.)

“I get really grumpy sometimes when things can’t be shown on film,” MoMA film curator Rajendra Roy tells the Times. Why can’t they?

By the standards of repertory cinema, Warhol’s oeuvre screens less frequently than, say, The Big Lebowski or The Rocky Horror Picture Show. But by the standards of the art world, the Warhol Museum’s preferred metric, are Warhol’s films any rarer than his canvases or silkscreens? How often do major traveling Warhol retrospectives come to town? It’s true that many institutions no longer possess suitable 16mm projection equipment or fail to maintain the old machines stored in some faraway basement a/v closet. Screening film properly certainly requires money, but so does mounting exceedingly valuable paintings and photographs and keeping them on public view for three to six months. Museum outlays for major exhibition preparation, handling, shipping, and insurance—which can run to hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars annually—would far exceed the cost of buying the finest 16mm projector available and staffing it with a competent projectionist. Local museums and galleries ranging from the Art Institute to Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Art to the Renaissance Society and the University Gallery at the Illinois State University in Normal have demonstrated the viability of such projects through their admirable commitment to 16mm and 35mm looping exhibitions in recent years.

Of course, Warhol’s gallery works circulate widely in reproduction, even if the originals are exceedingly difficult to see. If we can walk into the museum shop and purchase duly-licensed Campbell Soup mugs, Marilyn Monroe magnets, Mao Zedong posters, flowers t-shirts, and all the other paraphernalia, then what’s wrong with buying a DVD version of Couch or More Milk Yvette? One wonders, of course, whether our genteel gift shop would want to stock copies of The Nude Restaurant or Imitation of Christ.

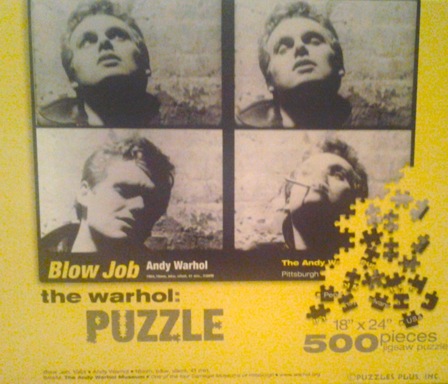

Salable or not, these films deserve to be seen—and there’s nothing wrong with providing access to audiences who have no realistic chance of ever seeing Warhol movies in their staid hometowns. Having seen many of the Warhol films on 16mm, I would also personally welcome the opportunity to revisit and study them in high-quality digital reproductions. I would be the first to put in a pre-order for a Blu-ray edition of The Chelsea Girls. (Merchandising the Warhol films is very much in its infancy, but I’ve already received one such licensed product as a gift: an exceedingly difficult 500-piece jigsaw puzzle derived from four Blow Job frame enlargements.)

Salable or not, these films deserve to be seen—and there’s nothing wrong with providing access to audiences who have no realistic chance of ever seeing Warhol movies in their staid hometowns. Having seen many of the Warhol films on 16mm, I would also personally welcome the opportunity to revisit and study them in high-quality digital reproductions. I would be the first to put in a pre-order for a Blu-ray edition of The Chelsea Girls. (Merchandising the Warhol films is very much in its infancy, but I’ve already received one such licensed product as a gift: an exceedingly difficult 500-piece jigsaw puzzle derived from four Blow Job frame enlargements.)

If we can all agree on the unvarnished good of access, then what’s the problem?

Back to the headline: Digitizing the films to save them. The article itself doesn’t make this claim, but it hardly contradicts it either. Preservation and access are equally important but they’re not synonymous. An archive can expertly preserve a film but fall short in making the work accessible to the public due to prohibitive loan terms or non-existent publicity. Equally, an archive can pursue an access agenda that doesn’t quite fulfill preservation imperatives.

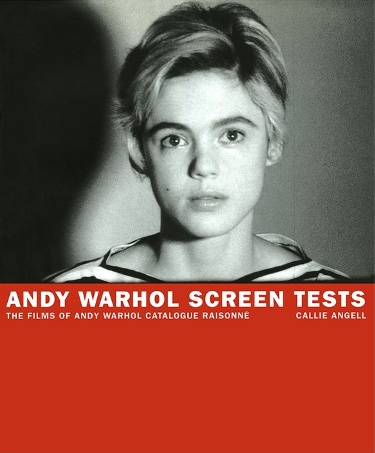

In the case of the Warhol films, I should stress, preservation and access efforts were hardly deficient: many of the films have already been lovingly preserved through traditional photochemical means and efficiently disseminated through MoMA’s Circulating Film and Video Library. There remain reels and reels of unpreserved, unaccessible work, though many constitute unfinished films, alternate versions, and dissembled scraps that require nontrivial curatorial judgment. It’s a giddy morass: Warhol cinema scholar Callie Angell once noted that non-existent Warhol films were often listed in the Film-maker’s Coop catalog—with the movies produced and shipped out as the orders came in!

Access is great, but digitizing Warhol films isn’t tantamount to saving them. Film is a proven archival medium, while the future of digital preservation is deeply uncertain. As NPR recently reported, paraphrasing UCLA Film and Television Archive’s Jan-Christopher Horak, “When you store something digitally it has to migrate once every three years, minimum. How much easier and cheaper … to stick a celluloid reel in a vault for a couple hundred years.”

But, the practical scholar might ask, how reliable is analog preservation when the viewing equipment might itself be obsolete? This is the root of Moore’s concern: that 16mm projection is becoming rarer and rarer. To paraphrase the film scholar and collector William K. Everson, hell would be a perfectly preserved 16mm print, but no projector to screen it.

This is a well-meaning but essentially counterproductive concern. There’s probably no quicker way to make 16mm obsolete than to proclaim it so. If we abandon 16mm, it will simply become a self-fulfilling lament: skills will atrophy, machines will degrade, spare parts will vanish, and new audiences will never get an opportunity to appreciate what made 16mm special in the first place.

Here’s the heartbreaking thing: Warhol’s films are among the best and most compelling arguments for the continued maintenance of 16mm exhibition. They’re not just artist’s works that happened to be created on 16mm; Warhol’s formal concerns and strategies are deeply shaped by the promises and limitations of 16mm film.

Here’s the heartbreaking thing: Warhol’s films are among the best and most compelling arguments for the continued maintenance of 16mm exhibition. They’re not just artist’s works that happened to be created on 16mm; Warhol’s formal concerns and strategies are deeply shaped by the promises and limitations of 16mm film.

Raw 16mm camera film was typically sold in 100’ rolls. This roll is the building block of Warhol’s early films: they’re largely single 100’ camera rolls, or unedited 100’ rolls joined together. Most films that we see—even most avant-garde films—are distillations: hours of shooting and editing that we absorb in highly manipulated, abbreviated form. Warhol’s silent films—shot at 24 frames per second (3 minutes per 100’ roll), but projected at 18 frames per second (4 minutes for the same roll)—take longer to watch than they did to make!

These extended, distended moments command a new and beguiling engagement. In Kiss, first screened serially, we watch close-ups of amorous assignations and keep guessing about the participants’ gender, orientation, and configurations for minutes on end. Sleep is a static study of Warhol’s sleeping lover, but the end-to-end assembly of 100’ reels continually challenges that stasis—a teasing anticipation that eventually resembles a stupefying but effective time-lapse paraphrase of Hollywood’s standard shot-reverse shot editing grammar.

When Warhol upgraded to an Auricon camera with direct optical sound recording, the raw camera roll retained its sway, at least for a while. Many Warhol talkies run 66 minutes—the length of two 1200’ rolls. Warhol’s performers are visibly aware of the camera and the amount of film left in the magazine: they ramble and mark time, or speed through the script when the end is nigh. The conclusion of a Warhol film is usually announced by the appearance of a flurry of white dots—an artifact of the identification number punched into the last few feet of the roll at the lab. Most filmmakers would discard this unusuable segment—not Warhol! Each film unfolds like a joyous death rattle, unencumbered and unafraid.

Perhaps these production aspects can be conveyed in digital copies; the experience of projecting a Warhol film cannot. Indeed, the experience is equally a product of 16mm projection. The first reel of The Poor Little Rich Girl cannot be focused, though many novice projectionists try anyway. This public struggle for clarity becomes a surprisingly effective parallel to the nebulous agency of PLRG star Edie Sedgwick; indeed, Warhol discovered that his first reel was out-of-focus, re-shot it correctly, but settled upon the “wrong” version.

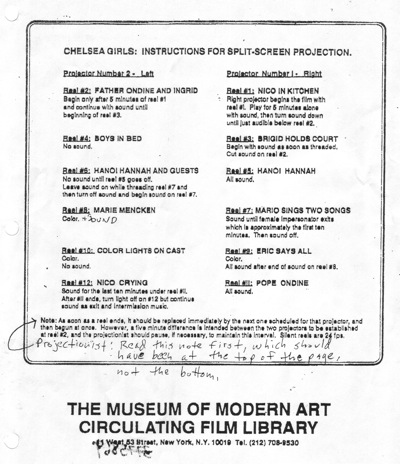

Warhol’s multi-projector films are astonishing, but largely because the synchronicity is rough and sometimes random. A digital presentation of The Chelsea Girls could follow the infamous projection instructions with more precision than any human operator could ever achieve, and it would necessarily lose something heroic in that translation. (Fun fact: it’s much easier to present double-projection works like The Chelsea Girls or Inner and Outer Space on a supposedly lowly pair of tabletop Eikis than it is on high-grade modern projectors like the Kinoton FP 38E. When the Dryden Theatre valiantly presented these works in 2008, the projectionists had to devote considerable labor to approximating the improvised, lo-fi astonishment of the films’ original exhibition: the Kinoton change-overs had to be disabled, the interlock modified, and the images bounced off mirrors.)

Finally, there’s the intangible, flickering presence of film itself. As already noted, Warhol’s movies tend toward the slow and the static; the randomized swirl of film grain is sometimes the most active part of a given shot. What happens when these minute variations are drafted into the routinized service of pixels and scanlines? One hopes that the digital Warhol movies of the future will look better than the anemic video version of Blow Job that I saw running continuously in a gallery corner—above the exit sign!—as part of SFMoMA’s 2009 exhibit ‘Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870.’

Finally, there’s the intangible, flickering presence of film itself. As already noted, Warhol’s movies tend toward the slow and the static; the randomized swirl of film grain is sometimes the most active part of a given shot. What happens when these minute variations are drafted into the routinized service of pixels and scanlines? One hopes that the digital Warhol movies of the future will look better than the anemic video version of Blow Job that I saw running continuously in a gallery corner—above the exit sign!—as part of SFMoMA’s 2009 exhibit ‘Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870.’

Writing in the Village Voice in 1994, when the Warhol Museum last contemplated a massive digitization project, Amy Taubin observed that “watching the lush Poor Little Rich Girl on video is like walking into a museum and seeing an 8 x 10 magazine reproduction hung in place of a painting. If there was anything that Warhol understood, it was how “presence” is medium-specific.” Significantly, the same article quotes a Warhol Foundation employee who frankly confides that the films are “an asset of the foundation. Our assets are in works of art, and we need to make money on our assets so we can continue our funding work.”

Some things have changed in the last twenty years. Archivists generally view access as a positive good, rather than a mercenary attempt to monetize cultural treasures. The Warhol films are a dubious mainstay of film history, rather than a naughty rumor. And video itself has become much more sophisticated, with higher resolution and truer color reproduction. Yet the wisdom of maintaining the Warhol films in the original format remains undiminished.

Again, preservation and access are not, or should not be, in competition. Decades ago, before digital even existed, some sober-minded film archivists noted an alarming trend: Cinémathèque française founder Henri Langlois and his followers regularly screened unique nitrate prints without first bothering to make backup copies on nonflammable acetate stock. Believing that his fire-averse peers didn’t even know the films in their own collections or which ones merited preservation, Langlois maintained that projection was an integral part of the curatorial and conservation process: to show is to preserve. Langlois was right, but so were his moderate colleagues who softly suggested ‘Preserve, then show.’ (Incidentally, this dictum was adopted as the title of an interesting anthology published by the Danish Film Institute in 2002.) Today, that motto might be ‘Preserve, then digitize.’ And keep your 16mm projector in fine, working condition—you never know when you might need it.