I’m pretty sure the first movie book I read cover-to-cover was Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, a high-calorie, sex ‘n’ drugs ‘n’ gross participation page-turner that maps the ascent and deflation of the “New Hollywood” filmmakers from 1967 to 1980. For a high schooler, it was a simple story with an irresistible through line and a cast of unsavory, irascible geniuses. Even without seeing all the films described in the book, this gossipy chronicle of long-haired movie brats sold a seductive premise: a vanished kingdom of personal, American auteurist cinema, wiped off the beach by Jaws and its blockbusting successors.

I’m pretty sure the first movie book I read cover-to-cover was Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, a high-calorie, sex ‘n’ drugs ‘n’ gross participation page-turner that maps the ascent and deflation of the “New Hollywood” filmmakers from 1967 to 1980. For a high schooler, it was a simple story with an irresistible through line and a cast of unsavory, irascible geniuses. Even without seeing all the films described in the book, this gossipy chronicle of long-haired movie brats sold a seductive premise: a vanished kingdom of personal, American auteurist cinema, wiped off the beach by Jaws and its blockbusting successors.

Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, published in 1998 shortly after the release of Boogie Nights, spawned a ’70s revival that has now calcified into a peculiar critical consensus. The best-seller inspired two talking-head documentaries (A Decade Under the Influence and another named for and adapted from the Biskind book) and endless appreciations of films that were hardly underappreciated in the first place: The Godfather, Taxi Driver, The Exorcist, The Last Picture Show, Apocalypse Now.

Nor can we forget the recent films that consciously channeled the “New Hollywood Renaissance,” taking the procedural aloofness of All the President’s Men as a retro Rosetta Stone: Argo, The Informant!, Michael Clayton, Zodiac, American Hustle, and host of less memorable pictures. Grain equals grit.

By now, the ’70s are accepted so reflexively as “Hollywood’s Last Golden Age” that there’s little point in quibbling. Still, it’s difficult to name another era in Hollywood filmmaking impervious to the critic’s naturally revisionist impulse. The Best Picture Oscar winners of the ’30s or the ’80s are roundly ridiculed, but the ’70s class (Midnight Cowboy, The French Connection, The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Annie Hall) remains lionized.

Indeed, the beloved ’70s canon is stubbornly small. The strained solidarity of Five Easy Pieces stands as a Sundance template and a wellspring of perpetually fashionable misogyny. Chinatown is still cited as a model of screenplay construction and elegant cynicism. The directors who garnered adulatory press coverage and stirring reviews in the ’70s—Altman, Scorsese, Coppola—are still regarded as the central figures of the era.

When re-examining the ’70s, it limits our understanding substantially to focus on individual filmmakers—and perhaps even individual films. The real story tumbles out only when viewed in aggregate. The free-for-all movie marketplace of the ’70s—when evangelical dramas rubbed shoulders with skin flicks and colossal old Hollywood follies like Lost Horizon competed with revolutionary political tracts—encompassed much, much more than a couple of film school dreamers breaking into big-boy features.

What makes the decade interesting is this very heterogeneity, the ever-shifting contours and limits of the commercial film landscape. The crumbling urban movie palaces of the ’70s played host to some frankly weird and staggering stuff—movies that never would have graduated from the back room of the elk’s lodge in the ’50s and ’60s and would be relegated to the direct-to-video catacombs in the ’80s and ’90s.

What makes the decade interesting is this very heterogeneity, the ever-shifting contours and limits of the commercial film landscape. The crumbling urban movie palaces of the ’70s played host to some frankly weird and staggering stuff—movies that never would have graduated from the back room of the elk’s lodge in the ’50s and ’60s and would be relegated to the direct-to-video catacombs in the ’80s and ’90s.

Scanning the movie ads that regularly confronted people in their morning newspapers in the ’70s provides an excellent cross-section of the shifting cinema, and offers incidental insights into the profound dislocations experienced by Nixon’s Silent Majority. Our friend Mike Quintero sent over an arresting Chicago Tribune clipping when we showed Thieves Like Us last October. In the May 25, 1974 edition of the Trib, Thieves Like Us was advertised alongside Foxy Brown, The Conversation, and Blazing Saddles (“from the people who gave you ‘The Jazz Singer’”). Local drive-ins pitched a forgotten G-rated live-action double feature from Walt Disney Productions—Snowball Express and The World’s Greatest Athlete.

Meanwhile, the 3 Penny Cinema promised a “New Adult Show Every Friday”. (This week’s bill: Carnal Cure, Lips, and Witchcraft.) The Rush Theatre offered a rival porno triple feature: Playboy Takes a Wife, Housewife on the Loose, and Group Therapy. The Aardvark peddled the X-rated Revolving Youth and Sweet Young Age. The aptly-named Termite promoted Magic Ring and Teacher’s Dream, both X. Le Image, the ‘Psychedelic Cinema’ at 750 N. Clark, boasted a special “A5 Unit All-Adult Program” that ran from noon to midnight. The Playboy Theatre announced that its program had been “held over due to overwhelming response”: Jean Eustache’s New Wave classic The Mother and the Whore (or, as rendered opportunistically by the Playboy, The Mother and the ?, with instructions to phone the theater for more details).

Forget porno chic. To judge by Page N16 of Chicago’s family newspaper, the smut now actually outnumbered the real movies. The traditional Hollywood movie, once the nation’s preeminent mainstream entertainment vehicle, had been supplanted almost overnight by Allergies Drive Her Wild. (Was that even a movie?)

Forget porno chic. To judge by Page N16 of Chicago’s family newspaper, the smut now actually outnumbered the real movies. The traditional Hollywood movie, once the nation’s preeminent mainstream entertainment vehicle, had been supplanted almost overnight by Allergies Drive Her Wild. (Was that even a movie?)

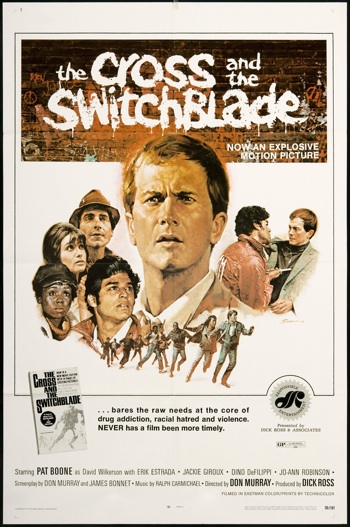

It wasn’t only the pornographers making aboveground headway. Our own Rebecca Hall has written suggestively of The Cross and the Switchblade—a Christian evangelizing film self-branded as “Responsible Entertainment” and released in IB Technicolor:

Like the hippies in the Jesus Movement, The Cross and the Switchblade was almost mainstream. The story was adapted from a best-selling autobiographical novel, and the film starred washed-up chart-topper Pat Boone in the role of pastor David Wilkerson, freelance evangelist and a young, then-unknown, Erik Estrada as one of the troubled youth. Slightly later evangelical films of the early 70s like If Footmen Tire, What Will Horses Do? (1971, Ron Ormond) or A Thief in the Night (1972, Donald Thompson) were circulated on 16mm and shown in church basements; Cross was released in conventional theaters in 35mm (by a short-lived film distribution division of the American Baptist Convention) and was advertised in local papers alongside Five Easy Pieces and various skin flicks.

Co-existence, a cultural aspiration that met so much opposition in the broader American landscape, thrived at the movies.

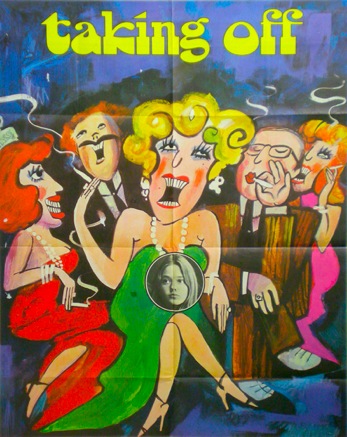

Distributor’s line-ups presumed a pluralistic audience. Big studios got behind European art cinema and promoted it as if it was homegrown product: Paramount released Bertolucci’s The Conformist and Warner Bros. put out Jan Troell’s The Emigrants and The New Land in dual-inventory subtitled and dubbed versions. Others bankrolled All-American excursions by established Euro brands—M-G-M sent Michelangelo Antonioni to Zabriskie Point and Universal backed Milos Forman’s Taking Off as part of a broader low-budget “youth slate” that also included Two-Lane Blacktop, The Hired Hand, and The Last Movie. (The ploy almost worked. Gene Siskel cited Taking Off, along with Alice’s Restaurant, as “the best youth films of the last-dozen years.” Forman’s American debut also received a hilariously tentative endorsement from PTA Magazine: “Except for a drunken parental strip episode, the film would be worth viewing by all ages.”)

Independent outfits went even further. It’s staggering to realize that one long-defunct company, Cinema 5 Distributing, released films by established masters like Ingmar Bergman (Scenes from a Marriage) and Satyajit Ray (Distant Thunder), politically-charged entertainment (Z) and documentaries (Marjoe, The Sorrow and the Pity), as well as Monty Python and the Holy Grail, insect overlord exposé The Hellstrom Chronicle, and a comedy called I Could Never Have Sex with Any Man Who Has So Little Regard for My Husband.

Independent outfits went even further. It’s staggering to realize that one long-defunct company, Cinema 5 Distributing, released films by established masters like Ingmar Bergman (Scenes from a Marriage) and Satyajit Ray (Distant Thunder), politically-charged entertainment (Z) and documentaries (Marjoe, The Sorrow and the Pity), as well as Monty Python and the Holy Grail, insect overlord exposé The Hellstrom Chronicle, and a comedy called I Could Never Have Sex with Any Man Who Has So Little Regard for My Husband.

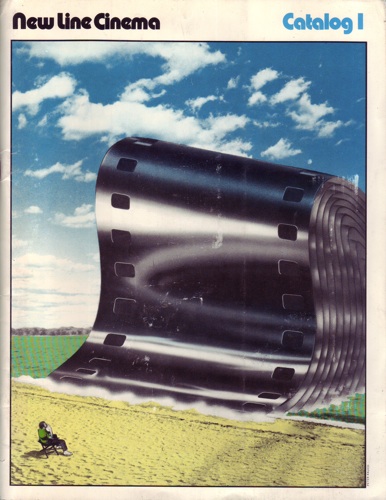

The scene wasn’t limited to traditional movie theaters, either. With some 5,000 active film societies in the US, largely on college campuses, distributors found outlets for very difficult material. Consider another favorite artifact—the first-ever catalog issued by upstart distributor New Line Cinema in 1973. Long before the company put itself on the map with low-budget teenage attractions like A Nightmare on Elm Street, New Line offered a precociously eclectic line-up for campus film societies, explicitly attuned to the ever-expanding definition of cinema:

Film in the 70’s offers an unprecedented variety of styles and influences which should be an important part of any campus entertainment and cultural program . . . .

As film programmers, you have the opportunity to go beyond standard film exhibition routine. Hollywood and traditional classics are no doubt an important part of a program, but film today goes further than these tried-and-true narrow limits. A campus film program should be more than just another movie theatre in your community. Many exciting film events are contained in this catalog and college is the only time when students will have the opportunity to be exposed to the important variety of independent film programming.

The catalog itself offered, among other things: art house films by Kenji Mizoguchi (The Crucified Lovers and Tales of the Taira Clan), Jean-Luc Godard (Sympathy for the Devil), Robert Bresson (Mouchette and Au Hasard Balthazar), Pier Paolo Pasolini (Medea) Norman Mailer (Maidstone), and Werner Herzog (Fata Morgana); reissues of campy exploitation films like Reefer Madness and The Cocaine Fiends; John Waters’s Pink Flamingos; concert docs about musicians as varied as Ravi Shankar, The Last Poets, and Earl Scruggs; Eyes of Hell, advertised as “the only 3-D film available in 16m/m”; the 1926 Japanese avant-garde silent film A Page of Madness; programs culled from the New York Festival of Women’s Films and the First Annual N.Y. Erotic Film Festival (“film is a four-letter word”); Stroke!, “a clinically accurate depiction of adolescent female masturbation,” per the Kinsey Institute; Together, “the first sexually-oriented film to play shopping-center and general release theatres”; Luminous Procuress, with the Cockettes; and Don’t Bank on Amerika, a documentary that depicted “the growth of a small surfer-college town into a gutsy revolutionary community in six short months.”

The catalog itself offered, among other things: art house films by Kenji Mizoguchi (The Crucified Lovers and Tales of the Taira Clan), Jean-Luc Godard (Sympathy for the Devil), Robert Bresson (Mouchette and Au Hasard Balthazar), Pier Paolo Pasolini (Medea) Norman Mailer (Maidstone), and Werner Herzog (Fata Morgana); reissues of campy exploitation films like Reefer Madness and The Cocaine Fiends; John Waters’s Pink Flamingos; concert docs about musicians as varied as Ravi Shankar, The Last Poets, and Earl Scruggs; Eyes of Hell, advertised as “the only 3-D film available in 16m/m”; the 1926 Japanese avant-garde silent film A Page of Madness; programs culled from the New York Festival of Women’s Films and the First Annual N.Y. Erotic Film Festival (“film is a four-letter word”); Stroke!, “a clinically accurate depiction of adolescent female masturbation,” per the Kinsey Institute; Together, “the first sexually-oriented film to play shopping-center and general release theatres”; Luminous Procuress, with the Cockettes; and Don’t Bank on Amerika, a documentary that depicted “the growth of a small surfer-college town into a gutsy revolutionary community in six short months.”

Critics rarely talk about movies as a business, leaving that beat to box-office watchers and industry-insider journalists. That’s a mistake, because a distributor’s slate and a theater’s booking policy profoundly affect not only what audiences see, but what constitutes a movie in the first place. This was the central question of ’70s cinema—and the fact that the ultimate answer was sci-fi blockbusters and slasher movies in no way diminishes the exhausting variety of mad wares that auditioned for the part. Indeed, with industry promoters promising that we’ll soon see many more satellite-fed sporting events and concerts at the local multiplex, we would do well to study the last great upheaval, the last time the notion of “the movies” was up for grabs.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Taking Off at the Patio Theater on April 2 at 7:30 in a 35mm print from Universal.