We’re all auteurists now. The notion that the director is primary author of a film, once a fringe idea debated in little magazines and grindhouse theater lobbies, is now the implicit premise of movie production, criticism, and advertising. When 3 Days to Kill is promoted as “A McG Film” and Pompeii is, contractually speaking, “A Film by Paul W. S. Anderson,” we must recognize that the debate is well settled.

We’re all auteurists now. The notion that the director is primary author of a film, once a fringe idea debated in little magazines and grindhouse theater lobbies, is now the implicit premise of movie production, criticism, and advertising. When 3 Days to Kill is promoted as “A McG Film” and Pompeii is, contractually speaking, “A Film by Paul W. S. Anderson,” we must recognize that the debate is well settled.

In our era of automatic auteurs, the contentious critical arguments of generations past can seem downright quaint, if not fitfully obscure. The once-controversial figure of the writer-director is a case in point.

In the earliest years of cinema, production roles were rarely delineated: actors and directors could improvise a scenario on standing sets, or a cameraman might call the shots. A quintessentially industrial art thrived on a pre-industrial division of labor. The growth of the studio system in the late 1910s and 1920s gradually forced filmmakers into more rigidly defined roles. The transformation culminated with the coming of sound, which introduced the idea of the modern screenwriter—not a semi-literate scenario scribbler or a witty intertitle aphorist, but someone who resembled a professional Broadway playwright.

The moguls aspired to employ sharp, college-educated playwrights, but the working conditions they offered were frequently demeaning and atrocious: no matter how fine a script was, the studio machinery would insist upon re-writes. The script would be passed from one employee to another as a matter of habit. One cannot overstate how thoughtlessly this imperative unfolded in practice. The process that birthed Midnight (1939) may be apocryphal, but it remains illustrative: unsatisfied with Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett’s draft, Paramount threw the script into the rewrite pool and programmatically assigned the task to another team—Wilder and Brackett, as it turned out, who submitted their uncorrected ‘revision,’ which was judged a tremendous improvement.

Under such circumstances, one can understand the writer’s impulse to direct his own script, if only to protect his material from further interference. There were frustrated attempts at writing-directing careers in the early ’30s, like the very talented Rowland Brown, but the breakthrough came with Preston Sturges’s 1940 sleeper hit The Great McGinty. Sturges famously sold the screenplay (an eventual Academy Award winner) to Paramount for a dollar with the proviso that he direct it himself, which opened the floodgates for established scripters like John Huston and Billy Wilder, and later Joseph L. Mankiewicz and Samuel Fuller. In studiospeak, members of this rarefied talent class were known as hyphenates—a mark of distinction, or perhaps a throwback to nativist complaints about “hyphenated Americans.”

In the auteurist upheaval of the 1960s, films were elevated to tributaries of personal sensibility—the expression of a director’s worldview. Yet the writer-director often received bafflingly short shrift in this landscape. If the director was already the de facto author of a film, shouldn’t a writer-director be a giant among men? Counterintuitively, Andrew Sarris argued that the hyphenates were developmentally debilitated:

Because so much of the American cinema is commissioned, a director is forced to express his personality through the visual treatment of material rather than through the literary content of the material. A Cukor, who works with all sorts of projects, has a more developed abstract style than a Bergman, who is free to develop his own scripts. Not that Bergman lacks personality, but his work has declined with the depletion of his ideas largely because his technique never equaled his sensibility. Joseph L. Mankiewicz and Billy Wilder are other examples of writer-directors without adequate technical mastery. By contrast, Douglas Sirk and Otto Preminger have moved up the scale because their miscellaneous projects reveal a stylistic consistency.

It’s all well and good to argue over the comparative craft of a Mankiewicz or a Wilder, but they’re pikers compared to the supreme writer-director of them all, the one who most flagrantly sought to disrupt the studio system that enriched him: Ben Hecht. It’s safe to say that Hecht didn’t give a damn about abstract style or technical mastery. Indeed, he didn’t give a damn about being a director at all. He is the anti-auteur.

It’s all well and good to argue over the comparative craft of a Mankiewicz or a Wilder, but they’re pikers compared to the supreme writer-director of them all, the one who most flagrantly sought to disrupt the studio system that enriched him: Ben Hecht. It’s safe to say that Hecht didn’t give a damn about abstract style or technical mastery. Indeed, he didn’t give a damn about being a director at all. He is the anti-auteur.

Hecht was, of course, the quintessential Chicago newspaperman—a hard-drinking cynic with an endless supply of jagged bon mots. Hecht’s Broadway hits The Front Page and Twentieth Century propelled him to the front ranks of Hollywood’s writer-for-hire racket. (His collaborator on both plays, Charles MacArthur, could have claimed equal stature, had he cared to play the guileless game.)

We scoff today when we learn that the author of Chinatown cashed a paycheck for a rewrite of Armageddon, or the team responsible for Sideways polished up I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry, but Hecht mortgaged his talent before these scribes could walk, contributing to forgettable backstage musicals, religious pabulum, sci-fi pictures, and sword and sandal adventures. Richard Corliss’s assessment from his 1974 book Talking Pictures still holds:

Ben Hecht was the Hollywood screenwriter … Indeed, it can be said without too much exaggeration that Hecht personifies Hollywood itself: a jumble of talent, cynical and overpaid; most successful when he was least ambitious; often failing when he mistook sentimentality for seriousness, racy, superficial, vital, and American.

This before acknowledging that a heavily-researched filmography “credits Hecht with just about every entertaining movie in the Hollywood sound era.” Among Hecht’s official credits: Underworld, The Great Gabbo, Scarface, Hallelujah I’m a Bum, Design for Living, Barbary Coast, Nothing Sacred, The Goldwyn Follies, Wuthering Heights, Spellbound, Notorious, Kiss of Death, Whirlpool, Monkey Business, and Ulysses. Uncredited: Back Street, Queen Christina, The Hurricane, Gone with the Wind, The Shop Around the Corner, Roxie Hart, Gilda, Rope, The Thing from Another World, Roman Holiday, The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell, and, at age 74, Casino Royale.

Hecht was the consummate fixer, a professional who could spend a week or two on a problematic script and turn it into a classic. His range of credits suggests no personal engagement, no integrity worth preserving. He may have wanted to protect his scripts, as a matter of professional credibility, but he had no passion, no drive to create the Great American Movie. In fact, Hecht claimed to have seen barely a dozen movies altogether by 1934.

Why, then, did Hecht turn to directing?

Why, then, did Hecht turn to directing?

Mostly, it was a crime of opportunity. Electric Research Products, Inc. (ERPI), a subsidiary of Western Electric, had a New York studio at its disposal. Hollywood had effectively abandoned East Coast production a few years before and few independent producers had the capital to start new projects in the depths of the Depression. ERPI set up a revolving line of credit (eventually, $800,000 worth) to encourage cash-strapped producers to use its facilities. The Eastern Service Studios Inc. (ESSI) in Astoria was soon buzzing with independent productions, including The Emperor Jones and Moonlight and Pretzels.

Still, ERPI wanted something bigger and offered a million dollars to Paramount to underwrite major New York productions. Paramount’s head of production, George Schaefer, extended the offer to Hecht and MacArthur, who would be given carte blanche to make whatever they wanted. They could demonstrate not so much that they could be good directors but that directors themselves were largely superfluous.

At first, Hecht and MacArthur were defiantly conceited. “Neither Charlie nor I had ever spent an hour on a movie set,” Hecht later wrote. “We knew nothing of casts, budgets, schedules, booms, gobos, unions, scenery, cutting, lighting.” Still, they couldn’t muck it up any worse than any of the other hacks.

Soon enough, reality set in. They panicked. They called Howard Hawks and pleaded, “For God’s sake, will you come back here for a week and help us. We don’t know a god damn thing about it.” Hawks was, of course, a busy professional whose stock was rising rapidly. Why should he drop everything to prop up these smartasses?

Hecht and MacArthur found a more accommodating collaborator in Lee Garmes, the great cameraman who had shot Scarface, City Streets, Morocco, and Shanghai Express, the latter a recent Academy Award winner for Best Cinematography. Garmes recalled the strange offer two decades later in an interview with George Pratt:

One day my agent called me in to the office. It was Myron Selznick.

He said, “Lee, how would you like to go to New York and be associated with Ben Hecht and Charlie MacArthur?”

I said, “Who the hell are they?”

And he says, “Well, they’re two of the famous movie writers … They’ve set up shop in New York to make some pictures and they have asked for a cameraman to join them that has directorial aspirations and knows a little bit about directorial things. They don’t believe in directors. They want to write and produce these pictures and they don’t want to have the typical Hollywood director because somehow or other they don’t feel that the stories they’ve written have always come off on the screen the way they should come off.”

They also offered to double his present salary as a Fox cameraman. He accepted.

Garmes was the right man for the job, and probably one of the only cameramen in Hollywood who would have embraced Hecht and MacArthur’s unconventional working methods:

Garmes was the right man for the job, and probably one of the only cameramen in Hollywood who would have embraced Hecht and MacArthur’s unconventional working methods:

My job with Ben Hecht and Charlie MacArthur was sort of co-director and co-producer. I helped out on the sets and also I supervised all the film editing on all the pictures . . . . After we got well-organized in the picture, the boys used to take turns in coming to the studio to direct. Ben Hecht would come in one morning and direct that day and Charlie would come in the next day. They’d alternate.

Sometimes they’d come in and they’d start in the background of the set playing backgammon. When I’d say, “Roll ‘em!”—why, as soon as the camera rolled over and we got the number on the camera, we said, “Action!” and they’d stop playing backgammon. If one of the actors made a mistake or blew up a line or something—why, they wouldn’t say, “Cut!” and I wouldn’t say, “Cut!” They would just start rolling the dice for the backgammon game and we knew then that we had to start the scene over again. This happened all the time. They were really a couple of screwballs, but I loved working with them, every minute of it.

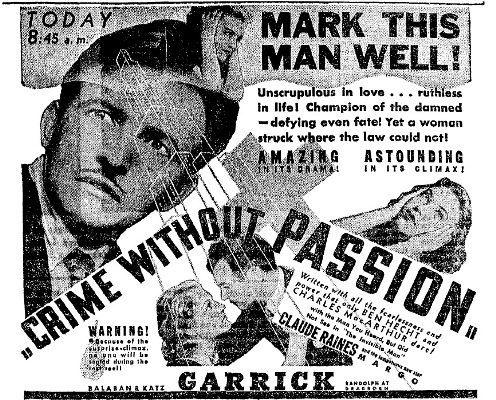

The first production turned out between backgammon games was Crime Without Passion. That the film has any fluidity and discipline at all is likely due to Garmes—there are some marvelous, dense tracking shots here hardly dictated by the script. The opening Slavko Vorkapich montage is also a stunner, sketching out a symphony of brooding stories in jumpy shorthand. The script itself doesn’t so much transcend cliché as dispense it in an extremely articulate, cosmopolitan form—a penny dreadful for the aesthetes. In keeping with the Hecht philosophy, it doesn’t conquer new frontiers in art but shows up all other practitioners as untalented charlatans. (This is, after all, the screenwriter who came out to Hollywood on the basis of Herman J. Mankiewicz’s telegram—“Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots.”)

Crime Without Passion predictably received an enormous amount of curious press coverage and unpredictably became a box-office hit. The Hecht-MacArthur-Garmes juggernaut continued with The Scoundrel but lost steam with Once in a Blue Moon, which was barely released. Hecht and MacArthur substituted Leon Shamroy for Garmes on their final Astoria production, Soak the Rich, and the great experiment ended ignominiously.

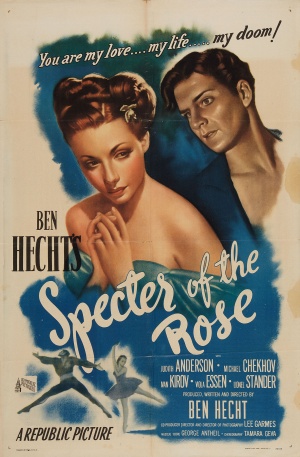

Still, for someone who allegedly found no glory in directing, Hecht returned to it three more times, with Garmes but without MacArthur. Their later projects did not find the same favorable terms as the Paramount-ERPI films and they trickled out over the course of a dozen years from three different studios: Angels Over Broadway from Columbia in 1940, Specter of the Rose courtesy of Republic in 1946, and Actors and Sin through United Artists in 1952.

“All of the Hecht-Garmes collaborations are moody and oppressive,” observes Corliss, “looking as if they were lit with a couple of flashlight batteries.” Angels Over Broadway has a bit more technical polish than that, but the description aptly applies to Specter of the Rose, one of the most unheralded and unaccountable movies ever made. Laid down in the languidly bitter world of ballet, Specter somewhat anticipates All About Eve and improbably surpasses the famous bitchiness of that picture. Hecht’s cast is undistinguished—Judith Anderson, Michael Chekhov, Ivan Kirov, Viola Essen—and they frankly lack the chops to keep up with his dialogue. No one could—the screenplay for Specter of the Rose hovers above the human plane, destined to be sullied by mere mortals. Its wit cannot be extricated from its arrogance. It’s pure l’esprit de l’escalier, nasty rejoinders so sophisticated and precise that they can only be constructed in hindsight—except in this movie, where they flow with impunity at an exhausting, real-time clip.

“All of the Hecht-Garmes collaborations are moody and oppressive,” observes Corliss, “looking as if they were lit with a couple of flashlight batteries.” Angels Over Broadway has a bit more technical polish than that, but the description aptly applies to Specter of the Rose, one of the most unheralded and unaccountable movies ever made. Laid down in the languidly bitter world of ballet, Specter somewhat anticipates All About Eve and improbably surpasses the famous bitchiness of that picture. Hecht’s cast is undistinguished—Judith Anderson, Michael Chekhov, Ivan Kirov, Viola Essen—and they frankly lack the chops to keep up with his dialogue. No one could—the screenplay for Specter of the Rose hovers above the human plane, destined to be sullied by mere mortals. Its wit cannot be extricated from its arrogance. It’s pure l’esprit de l’escalier, nasty rejoinders so sophisticated and precise that they can only be constructed in hindsight—except in this movie, where they flow with impunity at an exhausting, real-time clip.

Understandably, Specter of the Rose was a flop with audiences. Republic tried re-issuing it in the wake of The Red Shoes and even changed the film’s copyright notice to disguise it as new product, seemingly to no avail. Ultimately, the only thing that could have salvaged Specter of the Rose was a good, disciplined director—which was exactly the point. One can readily understand why the first generation of auteurists overlooked Hecht—he calls into question not only whether a director can make a personal statement, but whether he should. As is, Hecht and Garmes’s folly stands as Cinema Ground Zero, a profane masterpiece that has all the ingredients of an actual movie, but still can’t pass as one. Perhaps, in the end, Hecht was an auteur in spite of himself.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Crime Without Passion in a beautiful 35mm print at the Patio Theater on March 12. Print courtesy of Universal Studios. Please see our current calendar for further information.

FURTHER READING

Corliss, Richard. Talking Pictures: Screenwriters in the American Cinema, 1927-1973. Woodstock, N.Y.: Overlook Press, 1974.

Hecht, Ben. A Child of the Century. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954.

Koszarski, Richard. Hollywood on the Hudson. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2008.

Sarris, Andrew. “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962.” Film Culture 27, Winter 1962/63.