Let Us Compare Mythologies

Let Us Compare Mythologies

You’ve probably heard by now that the ongoing digital cinema conversion has fundamentally transformed the way movies are produced, distributed, and exhibited. Taken on their own, petitions and protests that aim to save 35mm film can look nostalgic, naïve, or simply Luddite. With 92% of American screens already film-free, this looks like a settled issue, with no outstanding questions.

The scene looks different at a farther remove. Cinema is hardly the only industry in the midst of a digital transition, after all, and comparative analysis promises fresh insight.

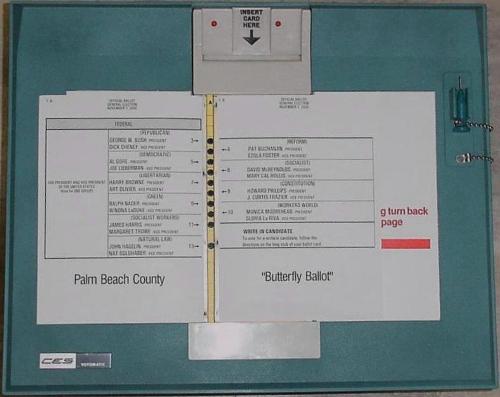

Let’s talk about the parallel upheaval in voting technology for a moment. In the wake of the Florida’s extraordinarily close vote totals in the 2000 presidential election, America focused anew on problems at the polling place. Poor ballot design, antiquated punch cards, obsolete lever machines—all came under post-mortem scrutiny. The technology was an incongruous, even dangerous, anachronism for the dot com economy. “In the age of the microchip,” CBS News opined, “the leadership of the free world is being decided by boxes of paper ballots with hanging and half-punched “chads,” leaving it to harried election officials to decide who meant to vote for whom.” In California, the ACLU cited the scattered usage of the much-maligned Votomatic machine as an impediment to equal protection guarantees and sued to delay a state-wide election until all the machines could be replaced.

On a 2001 episode of the PBS Newshour, a professor from George Washington University assured viewers that the voting technology problem could be easily licked. The plan itself was simple, provided that Congress found the will and the money to implement it:

NORTON GARFINKLE: Well, in our calculations, we found that the total cost of installing the new equipment throughout the country would be $1.2 billion. That’s less than 1 tenth of 1 percent of one year’s annual budget, federal budget of $2 trillion. Now, the easiest way to do this, the most straightforward way to do this, the thing that could accomplish the task within the next three months is if the Congress simply allocated a $600 million matching grant program to enable the states then to match the amount of money and then acquire the new equipment that’s needed. It really surprised us that the problem is so easily manageable. This is one of those problems that essentially is now highly visible but small enough to solve.

In a moment of bipartisan initiative that looks improbable today, Congress subsequently passed the Help America Vote Act, which promised, among other things, to subsidize the overhaul of outdated voting machines across the country. There were scattered anxieties about the transition, centering mostly on the security of the electronic voting systems and the scruples of equipment manufacturers like Diebold.

How did it all turn out, over a decade later?

Cinephiles and civilians alike can be forgiven for ignoring January’s release [PDF] of The American Voting Experience: Report and Recommendations of the Presidential Commission on Election Administration. As government reports go, it’s actually a pretty straightforward and breezy read. One section, in particular, aroused our interest because it reveals the limits of Garfinkle’s optimism:

Perhaps the most dire warning the Commission heard in its investigation of the topics in the Executive Order concerned the impending crisis in voting technology. Well-known to election administrators, if not the public at large, this impending crisis arises from the widespread wearing out of voting machines purchased a decade ago, the lack of any voting machines on the market that meet the current needs of election administrators, a standard-setting process that has broken down, and a certification process for new machines that is costly and time-consuming. In short, jurisdictions do not have the money to purchase new machines, and legal and market constraints prevent the development of machines they would want even if they had the funds.

When most people think of the crisis in voting technology, they think it passed with the 2000 election . . . . The voting technology crisis the country will soon experience has its roots in the 2000 election, but the nature of the problem is quite different than a decade ago. A large share of the voting machines currently in operation were purchased with federal funds appropriated in 2003 as part of HAVA’s provisions assisting in the transition away from punch card ballots and mechanical lever machines toward Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) and optical scan machines. Those machines are now reaching the end of their natural life cycle, and no comparable federal funds are in the pipeline to replace them.

The cinema parallel isn’t exact, but it’s damn close.

Also: damn edifying and damn frightening.

Throughout much of the last decade, studios were pressuring movie theaters to convert from 35mm projection to digital exhibition. Such a conversion—which could run between $50,000 to $100,000 per screen—required a large amount of capital that theaters simply didn’t have or wouldn’t invest in the new technology. This years-long impasse was finally broken by the Virtual Print Fee incentive—basically, an indirect cash transfer program where huge sums of conversion money flowed from the studios to the theaters via a third-party intermediate known as an integrator. Backed by the studios, the integrator would underwrite digital equipment purchase and installation for the exhibitors, leaving the theater owners with substantial debt. Every time the theater projected a movie via the new Digital Cinema Package format, the studio would pay a ‘virtual print fee’ to the integrator and slowly chip away at the exhibitor’s loan principal. The theater would be on the books and on the hook, but most of this obligation would eventually be covered by the producers—so long as the exhibitors kept showing movies and kept showing them digitally.

The Virtual Print Fee was designed as a one-time, extraordinary solution to unique problem. The studios made the calculation that the benefit of indirectly subsidizing the mass conversion of projection technology would considerably outweigh the cost. But what happens when the first wave of digital projection equipment breaks down or begins to show its age? This, too, will probably happen within a decade—probably around 2019 or 2020, when the machines installed to take full advantage of Avatar reach the end of their natural life.

Some are optimistic that the next wave of digital projector installations will boost adoption for high-end specs largely neglected in the first round: 4K resolution, rather than 2K, or laser technology instead of DLP. There’s plenty of growth potential—provided someone wants to pick up the bill. And at this moment, it’s not clear that anyone does.

What Comes After Cinema?

For all their inadequacies, analog voting machines and film projectors were relatively easy and cheap to maintain. True, many machines suffered from neglect, with decrepit models meted out disproportionally to poor and rural populations. It’s legitimate to ask whether anybody deserves to vote or watch a movie with decades-old equipment. That such a question could be posed in the first place, though, underlines something important: the equipment’s productive life was measured in decades, rather than years. The electronic voting machine and the digital projector are strictly short-term solutions. We made these choices, and now we have to face the consequences. It’s easy to agitate for revolution, harder to sustain it and plan its next development.

For all their inadequacies, analog voting machines and film projectors were relatively easy and cheap to maintain. True, many machines suffered from neglect, with decrepit models meted out disproportionally to poor and rural populations. It’s legitimate to ask whether anybody deserves to vote or watch a movie with decades-old equipment. That such a question could be posed in the first place, though, underlines something important: the equipment’s productive life was measured in decades, rather than years. The electronic voting machine and the digital projector are strictly short-term solutions. We made these choices, and now we have to face the consequences. It’s easy to agitate for revolution, harder to sustain it and plan its next development.

An outdated voting machine is a problem for a democracy, but it’s also a problem that will get solved sooner or later. The incentives are straightforward. Voters need some means of casting a ballot in the first place to accord legitimacy upon their representatives, so one imagines that there will be another Congressional appropriation to fix this looming crisis, if perhaps only at the eleventh hour. (Whether there will also be targeted, state-level efforts to impose voter ID laws and effectively suppress eligible voter turnout is, of course, another matter.) Voting machines may become obsolete, but voting itself cannot.

The same doesn’t necessarily hold true for cinema. Who will pay for the next overhaul and why? If the machine fails, why can’t the medium follow?

In 1999, the critic Godfrey Cheshire penned an extraordinarily prescient article about the future of digital cinema for the New York Press. Most industry watchers were predicting an imminent and essentially bloodless conversion to celebrate the new millennium, but Cheshire unpacked the implications in a way that Hollywood wasn’t necessarily ready to contemplate. Cinema as we knew it, Cheshire surmised, was rooted in the limitations of the film medium itself. Theaters screened feature-length movies because the costly, time-consuming process of striking film prints allowed for few alternatives. Movies were scripted, static, solid, classical by default. But digital opened up a whole new set of possibilities: theaters could screen live satellite feeds of concerts, sporting events, stage productions, and non-filmic entertainment previously confined to TV dissemination. Hence, the movie theater of the 21st century would build upon the paradigm of 20th century television, not 20th century cinema.

With many multiplexes and art houses these days giving over a movie screen or two to regular installments of National Theatre Live or opera from La Scala, Cheshire’s forecast looks eerily accurate. Ironically, Cheshire’s major prognostic error is imagining a fully-transformed cinema along the lines of TV, while remaining sketchy on the future of TV itself. With streaming increasingly replacing over-the-air viewing, TV has endured an even more profound upheaval then cinema over the last 15 years, but that doesn’t diminish Cheshire’s essential insight into the fundamental mutability of the cinema experience.

With many multiplexes and art houses these days giving over a movie screen or two to regular installments of National Theatre Live or opera from La Scala, Cheshire’s forecast looks eerily accurate. Ironically, Cheshire’s major prognostic error is imagining a fully-transformed cinema along the lines of TV, while remaining sketchy on the future of TV itself. With streaming increasingly replacing over-the-air viewing, TV has endured an even more profound upheaval then cinema over the last 15 years, but that doesn’t diminish Cheshire’s essential insight into the fundamental mutability of the cinema experience.

That mutability works both ways. Theaters might not need movies anymore. Will movies still need theaters?

Already theatrical releases have become something of a formality. The typical window between theatrical release and home video release has shrunk from nine months or more to three months or less. In some sense, the theatrical release is an extended advertisement for the ancillary iterations—DVD, Blu-ray, Ultraviolet, iTunes, Amazon Instant Video, etc. The theatrical release continues, in part because it’s a guarantee of coverage that newspapers and magazines would never lavish upon a strictly video on demand (VOD) title. Laboring under the edict that every new theatrical release demands a review, one dying medium enables another by a quirk of decorum. Cultural preeminence certainly has its advantages.

But is the moviegoing habit so strong that studios will spend billions of dollars to sustain the theater business in 2020 when its equipment becomes obsolete again? Whatever the landscape looks like, the exhibitors will not be negotiating from a position of strength. (Many may still be paying off old debts for worthless equipment.) The next wave of digital cinema could turn into a no-wave.

Obsolescence on Demand

The ascent of VOD is undeniable. Over the last few years, it’s been pioneered by upstarts and boutique labels—Magnolia, Roadside Attractions, IFC, and Radius, the VOD arm of The Weinstein Company. As a matter of principle, the big theater chains like Cinemark and Regal refused to screen titles released simultaneously to the VOD market. Then again, they likely wouldn’t play much product from these indie distributors to begin with—and the distributor’s business model doesn’t depend on opening on 2,000 or 3,000 screens either. When you don’t have to recoup a nine-figure investment, you can take that kind of risk. The VOD experimenters could go after unaffiliated theaters or small chains. So long as they could demonstrate that simultaneous VOD availability did not completely gut theatrical revenue, everyone was happy. Decent theatrical grosses for mid-profile VOD fare like Margin Call and Arbitrage partially alleviated exhibitor concerns. (Indie veteran John Sloss even dared distributors to release VOD grosses alongside traditional box office numbers, a suggestion that has been slow to gain traction.)

The major studios, which have much more invested in each release, have been comparatively shy about VOD. They could not dip a toe in the VOD waters and sustain a retaliatory boycott from the theater chains. Universal tried such an experiment in 2011, when it announced that Tower Heist would be available on VOD three weeks after its theatrical bow. Cinemark and National Amusements swiftly refused to book Tower Heist and Universal backed down.

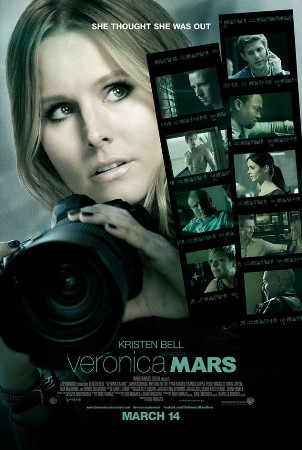

The theaters’ threats bought more than two years of negotiated peace with the studios on the VOD question, but the balance of power is shifting. On March 14, Warner Bros. will simultaneously release Veronica Mars to theaters and VOD. The studio claims that it’s a one-off deal, dictated by the terms of the unusual Kickstarter campaign that financed the movie. Will a successful VOD roll-out really be limited to a one-off? And again, will major studio VOD releases remain taboo for the duration of the decade? If not, the number-crunchers at the studios will doubtless ask whether they really need to underwrite another round of digital projector purchases in 2020 when their exhibitor partners return, hat in hand.

The fundamental issue here—the thing that unites art and commerce, calculation and aspiration—is underlying business model for hardware manufacturers. Cinema in the 20th century grew up around a familiar industrial paradigm. Companies like Ballantyne Strong did not base their revenue projections on the expectation that clients would be replacing their equipment every five to ten years. They treated their merchandise like a sturdy investment to be serviced, not a consumer product to be upgraded. There’s no Moore’s Law for film projectors.

The conversion has shifted the paradigm and the expectations of equipment manufacturers in a dangerous direction. Should a digital projector be thought of like a film projector or more like a computer or a tablet? If the latter paradigm prevails, what happens to the marketplace when theater owners don’t wind up camping outside the Barco factory like a bunch of yuppies hoping to be the first on their block to land an iPhone 5S?

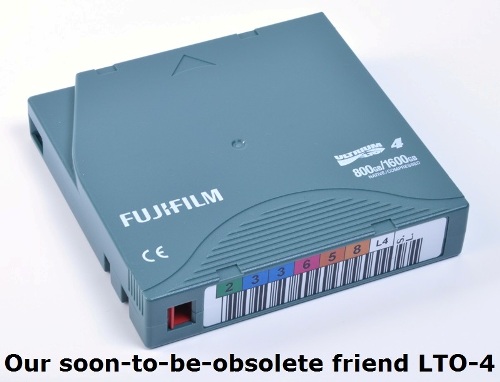

The problem extends beyond the exhibition sector. It encompasses our whole brave new moving image hippodrome. As Matthew Dessem observed in an outstanding state-of-the-field overview on The Dissolve, the new standard for data preservation—LTO tape—is no standard at all:

Since 2000, new generations of LTO technology have been released every two years or so—new tapes and new drives—and they’re only backward-compatible for two generations. So a film that was archived to tape in 2006 using then-state-of-the-art LTO-3 tapes can’t be read by the LTO-6 drives that are for sale today.

… [N]either the manufacturers of LTO tapes nor the bulk of their clients have much incentive to develop a true archival format. Tape and drive manufacturers thrive on planned obsolescence, just like the rest of the computer industry. And companies who purchase LTO tapes for backups not only don’t need the data preserved longer than the seven years required for Sarbanes-Oxley compliance, they don’t want it preserved longer, because as long as the data exists, it’s discoverable in lawsuits. It’s possible that a digital format that meets these archival requirements will someday be developed—but it’s unlikely to happen anytime soon.

The problem is not just theoretical. As Jan-Christopher Horak recently noted, UCLA Film & Television Archive had to migrate its restoration of The Red Shoes from LTO-3 to LTO-5—at a cost of over $15,000. (Just imagine how much UCLA will have to pay to migrate every title, every three to four years, and suddenly the carping of the theater owners looks like small potatoes.)

The problem is not just theoretical. As Jan-Christopher Horak recently noted, UCLA Film & Television Archive had to migrate its restoration of The Red Shoes from LTO-3 to LTO-5—at a cost of over $15,000. (Just imagine how much UCLA will have to pay to migrate every title, every three to four years, and suddenly the carping of the theater owners looks like small potatoes.)

There’s an inescapable conclusion here: the forces of the free market and the wisdom of the tech industry are not aligned with the long-term viability of cinema, whether it’s defined as 35mm or DCP. The preservation and growth of cinema likely needs some combination of state support, non-profit initiative, and private citizen enthusiasm—just don’t expect the result to look like any paradigm we already know.