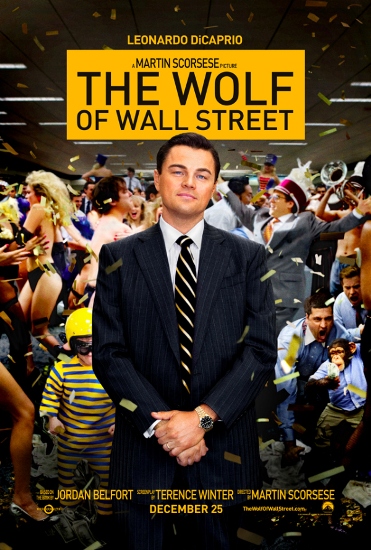

No sooner had this blog observed that film’s death watch was leveling off than the Los Angeles Times delivered a bombshell: Paramount Pictures was the first of the big studios to drop 35mm, with Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues being its last title released on film. Henceforth, all Paramount titles would be DCP only, beginning with The Wolf of Wall Street. (How ironic that, in one of Wolf’s best scenes, Leonardo DiCaprio teaches his charges how to scam small-time investors by selling them shares of Kodak before moving on to worthless penny stocks.)

No sooner had this blog observed that film’s death watch was leveling off than the Los Angeles Times delivered a bombshell: Paramount Pictures was the first of the big studios to drop 35mm, with Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues being its last title released on film. Henceforth, all Paramount titles would be DCP only, beginning with The Wolf of Wall Street. (How ironic that, in one of Wolf’s best scenes, Leonardo DiCaprio teaches his charges how to scam small-time investors by selling them shares of Kodak before moving on to worthless penny stocks.)

Richard Verrier’s Times piece was thinly sourced, with the studio refusing to comment and the “theater industry executives” who leaked the news remaining anonymous. The article included no quotes from the memo itself, nor any indication of how many people received it. In some ways, this is old news. Anchorman 2 was released a month ago, and the gist of the Paramount memo was circulating on specialist message boards like film-tech.com back in November. At least one forum member cited a Wolf booking at a 35mm venue, but the balance of the evidence suggests that the phantom memo is, in fact, true.

So, what do we take from this event, other than a swell piece of movie trivia fit for a future Jeopardy! tournament?

Although such an announcement was expected for some time, few wanted to take credit for it. As the Times explained:

Paramount has kept its decision under wraps, at least in Hollywood.

The reticence reflects the fact that no studio wants to be seen as the first to abandon film, which retains a cachet among some filmmakers. Some studios may also be reluctant to give up box-office revenue by bypassing theaters that can show only film. About 8% of U.S. movie theater screens are equipped to show movies only on film.

A broader perspective makes Paramount’s decision less surprising. To the casual observer, 8% of American screens sounds like a significant figure, especially when many movies barely recoup costs or fail outright. Wouldn’t the studios want every possible screen available—film, digital, or otherwise? Can the industry afford to simply write off this stubborn 8%? In absolute terms, if we accept the commonly cited figure of 40,000 screens, the film laggards represent a not-insubstantial 3,200 screens.

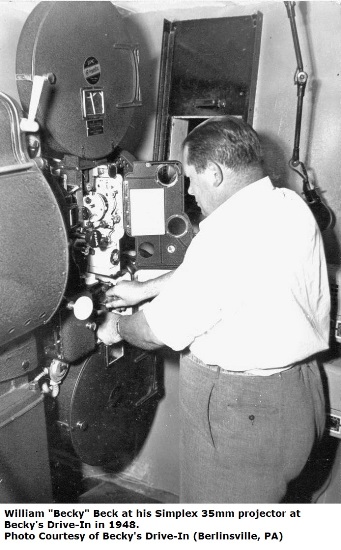

Does that mean that each screen represents a principled film holdout, dedicated to maintaining the material heritage of the medium? Of course not. Many of the non-digital screens are simply low-volume outposts, without the audience or cash flow to justify the $50,000-$100,000 per-screen investment required for a digital conversion. We’re talking about rural theaters, drive-ins, military bases, second-run houses, undercapitalized independents, and the like. These locations may account for 8% of the total screens, but they surely represent much less than 8% of total industry revenue—probably something closer to 2 to 3%, if that. Should the studios continue to support an expensive system of parallel film-and-DCP distribution infrastructure to nurture this declining market or simply shutter low-performing locations like any rational national retail chain?

Does that mean that each screen represents a principled film holdout, dedicated to maintaining the material heritage of the medium? Of course not. Many of the non-digital screens are simply low-volume outposts, without the audience or cash flow to justify the $50,000-$100,000 per-screen investment required for a digital conversion. We’re talking about rural theaters, drive-ins, military bases, second-run houses, undercapitalized independents, and the like. These locations may account for 8% of the total screens, but they surely represent much less than 8% of total industry revenue—probably something closer to 2 to 3%, if that. Should the studios continue to support an expensive system of parallel film-and-DCP distribution infrastructure to nurture this declining market or simply shutter low-performing locations like any rational national retail chain?

In the old Hollywood business model, the answer might not be so clear-cut. Maximum revenue was extracted at every possible level of the industry, with a complex system of runs, clearances, and zones made possible through the vertical integration of the industry. Since the same outfits manufactured, distributed, and sold the product, they usually kept the largest, most profitable locations for themselves and allowed the lesser screens to be run by small-time operators. If these bottom feeders wanted to offer a couple bucks to run a beat-up print of a movie that played the downtown palaces a year ago, why leave money on the table? Since most every studio booked their titles as a slate, the individual performance of each title hardly mattered; a predictable, systematized revenue stream that yielded shareholder dividends was more important. The studio (often back-stopped by a respectable New York bank) spent all the capital and reaped all the rewards.

This arrangement came crashing down in 1948 when the Supreme Court ordered Paramount and its co-defendants to divest of their theater chains and earn an honest, non-monopolistic living. The studio system changed dramatically; without a captive market contracted to play each and every film on a slate, the overhead costs associated with an ever-churning production assembly line became unsustainable. No standing sets, no seven-year contracts, no new picture shipped every single week. Each movie became its own isolated business proposition, with theatrical (and later, ancillary) revenue closely scrutinized.

Today’s studios release around ten to twenty movies a year and the financial arrangements are as complicated as the production logistics. Rather than emanating from a mogul’s head or a studio script department, movies come packaged by independent producers who yoke their projects to studio largesse. The studios don’t provide facilities or talent, but access to financing. All the studios, save Disney, have financing partners like Legendary, Skydance, or RatPac who underwrite most (or all) of the production costs and split the gross proceeds. In some cases, the production cost is born entirely by the financing partner, the studio handling marketing and distribution only.

It’s only in this context that Paramount’s Wolf of Wall Street decision makes sense.

Paramount has scaled back more seriously than any other major studio. They released eight films last year—none of them record-breaking, global blockbusters, but none of them embarrassing flops like R.I.P.D. or 47 Ronin either. They released nothing theatrically between World War Z on June 21 and Jackass Presents Bad Grandpa on October 25—a very nearly unprecedented four-month gap. Playing a conservative game without preposterously expensive would-be franchise launchers like The Lone Ranger, the operation is lean and disciplined enough to take a calculated risk like dropping 35mm release prints.

The Wolf of Wall Street is also the ideal test case for the proposition for a variety of reasons. At 179 minutes, it’s a long film. Every extra minute requires more film stock in every release print, which costs money; so long as the DCP file still fits on a standard hard drive, there’s no additional, per-unit expense associated with this indulgence. (Whether the theaters are content to schedule fewer showtimes, and thus sell fewer tickets, is another matter.) Business for Wolf has been concentrated on the coasts and in high-density urban markets, where conversion compliance is undoubtedly higher. And given its infamously R-rated anal aerobics, The Wolf of Wall Street doesn’t exactly invite heart-tugging headlines. (Just imagine: “Mom ‘N’ Pop Theater Shutters, Can’t Show Scorsese’s Latest ‘Ludes ‘N’ Hookers Fantasia on Film.”)

The Wolf of Wall Street is also the ideal test case for the proposition for a variety of reasons. At 179 minutes, it’s a long film. Every extra minute requires more film stock in every release print, which costs money; so long as the DCP file still fits on a standard hard drive, there’s no additional, per-unit expense associated with this indulgence. (Whether the theaters are content to schedule fewer showtimes, and thus sell fewer tickets, is another matter.) Business for Wolf has been concentrated on the coasts and in high-density urban markets, where conversion compliance is undoubtedly higher. And given its infamously R-rated anal aerobics, The Wolf of Wall Street doesn’t exactly invite heart-tugging headlines. (Just imagine: “Mom ‘N’ Pop Theater Shutters, Can’t Show Scorsese’s Latest ‘Ludes ‘N’ Hookers Fantasia on Film.”)

But most important, The Wolf of Wall Street was financed entirely by production partner Red Granite. Paramount is responsible for distribution and marketing costs (which may be considerable, given Wolf’s Oscar ambitions), but it does not need to recoup the film’s $100,000,000 production budget. Paramount stands to take a substantial distribution fee regardless, while Red Granite must make its money back through international pre-sales and eventual domestic profits. Ultimately, it’s in everyone’s interests for The Wolf of Wall Street to do blockbuster business, but the bottom line risk of bypassing marginal, film-only venues is quite minimal for Paramount.

What about the Times’ speculation that the move might alienate pro-film talent? This is harder to quantify, and few working filmmakers can afford the luxury of blowing up an in-development project to make a polemical point about celluloid origination.

Still, there are a surprising number of filmmakers publicly rallying to film’s defense, including unlikely allies like Joe Swanberg, whose latest Sundance entry, Happy Christmas, is the first thing he’s shot on 16mm since film school. Alex Ross Perry, sounding a bit like a confident professor who stresses that we live in an era of ‘late capitalism,’ reports that “shooting on film isn’t a choice, it is the default decision and video is a choice.” Other established figures like James Gray continue to mount a defense of film at festival appearances around the world:

But I think the power of what is new is really in some ways what is damaging, because let’s say everyone was shooting digital — the whole world, Steven Spielberg, Chris Nolan, all those guys, they were all shooting digital — and then all of a sudden I came out with this product and said “Well there’s this thing, it doesn’t see in pixels, it sees in grain, which is more like your eye sees, and it has a better contrast ratio than digital and it has a better color representation,” everybody would be like “This new thing — film — I gotta change to film.” I can’t understand why everyone wants to migrate to a medium that is — in my mind — objectively worse.

It’s difficult to imagine filmmakers—even ones as powerful as Spielberg and Nolan—reversing the trend. Nevertheless, there has been a remarkable amount of press coverage of the Paramount decision. (It’s reflective of film’s receding role in American life that many sympathetic websites illustrated stories about the winding down of 35mm film with generic images of 16mm film reels.) There’s a new online petition circulating, too, which asks UNESCO to protect film by designating the medium itself as World Heritage. It’s instigated by cinematographer Guillermo Novarro’s contention that film is “the Rosetta Stone of our times.” (For what it’s worth, the last project that Novarro shot, Pacific Rim, was photographed digitally on the Red Epic camera.)

No one could accuse the film advocates of sitting on the sidelines. The petition reflects widespread energy among filmmakers, archivists, curators, and everyday folks. We’d like to think we play a small part in it: our Film Society recently implemented a projectionist training seminar and sent a representative to Alternative Measures, a Colorado Springs conference devoted to the future of artist-run film labs.

The optimism is infectious, and compelling up to a point. Even if Kodak discontinues film, the thinking goes, boutique labs and individual artists will manufacture film and process it in their bathtubs. Hipsters will demand film, just like vinyl. If the Polaroid process can be resurrected, why not motion picture film?

Fact is, motion picture film is an enormously complicated, excruciatingly precise, industrial undertaking. Let’s not kid ourselves about the capital required. It’s quite easy for an upstart to manufacture black and white 16mm camera stock, for example. The problem arises when one honestly accounts for the breadth and diversity of the last century’s film processes. Producing color emulsion or interpreting decades-old timing instructions requires expensive equipment, exquisite craftsmanship, and knowledge that cannot be gleaned from an instruction manual.

Fact is, motion picture film is an enormously complicated, excruciatingly precise, industrial undertaking. Let’s not kid ourselves about the capital required. It’s quite easy for an upstart to manufacture black and white 16mm camera stock, for example. The problem arises when one honestly accounts for the breadth and diversity of the last century’s film processes. Producing color emulsion or interpreting decades-old timing instructions requires expensive equipment, exquisite craftsmanship, and knowledge that cannot be gleaned from an instruction manual.

It’s quite possible to imagine an enormous international commune-laboratory with rows of ultrasonic cleaners and room-spanning processing tanks. But what about the lifetimes of accumulated knowledge of the lab veterans who need to earn a living from this stuff? Yes, such knowledge could be reverse-engineered or deduced from scratch, as it was years ago. But that innovation happened in a robust market, when substantial R&D investment could yield lucrative returns. What’s the incentive now?

Uncomfortably for some celluloid advocates, robust copyright terms may be the best hope for film’s survival. There may not always be profit to be made from striking new prints, but there will be substantial corporate incentives for maintaining the knowledge base around film. As long as there’s a dime to be made from The Wizard of Oz, Lawrence of Arabia, or Grease, there will be people and machines that can conserve, handle, analyze, and decode these mysterious old film stocks.

The enormous strides in digital restoration over the last decade confirm, rather than refute, this point: archivists and asset managers still search for the best extant film element, which is the essential starting point for any quality restoration. Every time a new software package or consumer platform comes along, archivists frequently scrap their most recent restoration attempt and return anew to the original film elements, hoping to bring out qualities that yesterday’s shiny new toy couldn’t quite capture.

We come now to the ideological conflict at the heart of the varied campaigns to save film. They’re often pitched as a matter of cultural heritage, pure and simple—something that needs to be done, even if it’s not sufficiently profitable for the private sector. Perhaps, as Jonas Mekas has suggested, national film laboratories are the solution to this frustrating problem.

Yet film as we know it was always an industrial-scale, profit-oriented process, even if some of its finest products (home movies, avant-garde films) were not. We may not like this fact, but any mature assessment of the history of the medium must account for it, along with the environmental consequences of mass manufacture and destruction of film stock. There may well be another film paradigm, but it won’t represent triumphant continuity with twentieth-century cinema. Film will be something new again and we can’t wait to see it.