Global Recession Saves 35mm

Global Recession Saves 35mm

Tradition dictates that this blog publish an end-of-year overview looking back on distribution trends and chronicling the fate of film exhibition. Compared to the past two years, we saw fewer signal events in 2013—no headline-grabbing bankruptcies, less saber-rattling ‘do it or die’ announcements from the studios, fewer (or, at least, less hysterical) media stories chronicling the fate of struggling, straggling mom ‘n’ pop operations. Generally speaking, 2013 was the year that digital cinema became so normalized as to be unremarkable.

With the wide-scale digital conversion of first-run movie exhibition accepted as a fait accompli, the belligerence and defiance have cooled considerably. Back in 2011, studios strongly suggested that 35mm prints would be unavailable after 2013. The message was clear: gobble up the carrot of 3D surcharges and labor-saving automation now, before we bring out the stick of absolutely refusing to accommodate your out-moded film equipment. This warning did its job: by the end of 2013, so many theaters had converted that threats as such were less necessary. The threats were also less credible: Kodak, newly emerged from bankruptcy, reports that the studios have contracted for raw film stock through at least 2015.

Hypothetically, all this film stock is needed to serve the international market, which is a patch-work of high compliance territories like Western Europe and slow-growth areas like Latin America. Greece has only converted 20% of its screens, says Kodak, the rare company to cite the debt-ravaged country as a good business prospect. One industry consultant acknowledged that digital equipment manufacturers should expect a major slowdown, perhaps even a “sales cliff,” because exhibitors simply cannot sustain upgrades in the midst of a global credit crunch.

In the US, at least, the hold-outs are generally independently-owned, low-capacity, low-revenue theaters. By definition, they lack the leverage and the cash flow to justify the financial outlay (anywhere between $50,000 – $100,000 per screen) required for a conversion. If they’re forced out of business, whenever the reckoning comes, the impact on Hollywood’s bottom line will be minimal.

With the Landmark Century Centre converting to DCP in September 2012, Chicagoans literally had no options for catching first-run titles in 35mm this year. The Gene Siskel Film Center and Music Box—which both lean toward art fare, foreign films, documentaries, and revivals—still maintain 35mm equipment, but new product is often screened digitally. Even when a venue’s managers make every effort to screen film on film, as the Siskel and the Music Box do, 35mm prints are simply often not available. With fewer and fewer prints being struck, distributors are justified, economically if not morally, in saving them for the venues that literally have no other options. Principles be damned, the venues receive the movie in whatever format is available that week, a situation acknowledged in a recent issue of the Film Center’s Gazette. Thus, the Siskel screens Frances Ha in DCP while Doc Films shows it in 35mm; the reverse scenario played out with The Bling Ring. (Both titles were shot digitally.)

With the Landmark Century Centre converting to DCP in September 2012, Chicagoans literally had no options for catching first-run titles in 35mm this year. The Gene Siskel Film Center and Music Box—which both lean toward art fare, foreign films, documentaries, and revivals—still maintain 35mm equipment, but new product is often screened digitally. Even when a venue’s managers make every effort to screen film on film, as the Siskel and the Music Box do, 35mm prints are simply often not available. With fewer and fewer prints being struck, distributors are justified, economically if not morally, in saving them for the venues that literally have no other options. Principles be damned, the venues receive the movie in whatever format is available that week, a situation acknowledged in a recent issue of the Film Center’s Gazette. Thus, the Siskel screens Frances Ha in DCP while Doc Films shows it in 35mm; the reverse scenario played out with The Bling Ring. (Both titles were shot digitally.)

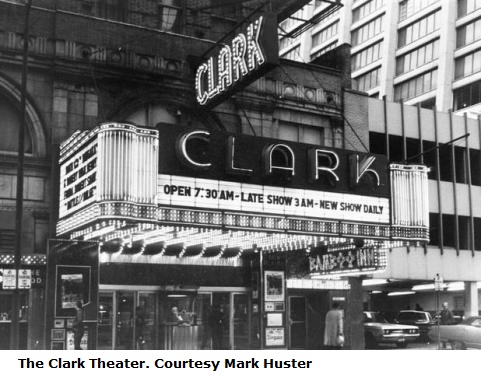

Even for audiences for who don’t value film exhibition for its own sake, the recent industry shift has fundamentally changed where and how we see movies in the first place. “Is there any theater in Chicago where one might experience exploitation fare as audiences did in the 60s or 70s?” asked Ben Sachs recently on the Reader’s blog. Properly speaking, there are no theaters marginal enough to qualify as marginal anymore. With first-run exhibition more capital-intensive than ever thanks to DCP, no one can operate a theater on a shoestring. Witness the recent gentrification of the Logan Theater—a venue that, in the film era, didn’t even regularly use aperture plates! A true grindhouse like the long-gone Clark Theater is unimaginable.

It Really Feels Like a Movie!

It is astonishing to realize that, in a little over five years, 35mm film has gone from a widely-supported exhibition format to the sole province of non-theatrical venues: public libraries like Northbrook, college-affiliated groups like Doc Films at the University of Chicago and Block Cinema at Northwestern, and oddball hybrids like the Brew & View.

This scrappy fact stands in marked contrast to the view still prevalent in the archival community that film’s salvation will come through major museums, festivals, and high-powered cultural institutions. The Chicago International Film Festival, which theoretically possesses the clout to demand 35mm prints for its gala events and centerpiece screenings, screened no 35mm prints this year. Last year, the Festival screened 18 titles on 35mm. (The California-based Arclight, which will bring its premium experience business model to Chicago in 2014, hints that it hopes to become a new home for the Festival and says it will also install 35mm projectors in one auditorium.)

The New York Film Festival, arguably the most prestigious festival in the country, screened a few prints this year, but the vast majority of its offerings were DCP. At an NYFF press conference, Joel Coen lamented that, in all probability, Inside Llewyn Davis would be the last movie he and his brother Ethan make on film—though the NYFF itself screened it digitally. Ironically, the Coens are themselves major figures in the broader conversion story: their O Brother Where Art Thou? was one of the first studio feature that was shot on 35mm but color-corrected entirely through the Digital Intermediate (DI) process. In 2000, this experimental workflow was necessary to tweak color values in ways that traditional photochemical processing could not achieve. Subsequently, though, the DI became standard practice for almost every American feature film, even ones with much more conventional technical demands.

The New York Film Festival, arguably the most prestigious festival in the country, screened a few prints this year, but the vast majority of its offerings were DCP. At an NYFF press conference, Joel Coen lamented that, in all probability, Inside Llewyn Davis would be the last movie he and his brother Ethan make on film—though the NYFF itself screened it digitally. Ironically, the Coens are themselves major figures in the broader conversion story: their O Brother Where Art Thou? was one of the first studio feature that was shot on 35mm but color-corrected entirely through the Digital Intermediate (DI) process. In 2000, this experimental workflow was necessary to tweak color values in ways that traditional photochemical processing could not achieve. Subsequently, though, the DI became standard practice for almost every American feature film, even ones with much more conventional technical demands.

“I’m glad we shot on film,” Joel Coen said, “but it’s a hybrid thing right now. It all goes into a computer and it’s all heavily manipulated. But still, there’s something that looks different.” Indeed, Inside Llewyn Davis—which just won a Best Cinematography citation from the National Society of Film Critics for Bruno Delbonnel’s delicate, wintry images—does look different for being shot on 35mm and it’s a damn shame that discerning festival audiences have largely seen it projected digitally. (Chicagoans who want to catch Inside Llewyn Davis on 35mm have had only one chance so far: a quietly-promoted sneak preview held at Block Cinema on Dec. 5, with the subsequent commercial run in DCP. Seeing films on 35mm will seemingly require much more planning and semi-clandestine intrigue in the future, which is one reason the Film Society began tracking such screenings on Celluloid Chicago.)

Whether the Coens lack the clout to insist on 35mm screenings or regard the projection format as an inconsequential afterthought in our hybrid age is largely beside the point. The Coens are among a handful of A-list directors whose work testifies to the continued artistic vitality of shooting films on film (along with Paul Thomas Anderson, James Gray, Christopher Nolan, Terrence Malick, J. J. Abrams, Lee Daniels, and Quentin Tarantino) and even they can’t or won’t or don’t screen on 35mm.

Consider, too, the Hollywood Report’s recent account of Wong Kar-Wai’s appearance at the New Beverly Cinema to promote his Oscar hopeful The Grandmaster:

Consider, too, the Hollywood Report’s recent account of Wong Kar-Wai’s appearance at the New Beverly Cinema to promote his Oscar hopeful The Grandmaster:

Wong and [cinematographer Phillippe] Le Sourd were particularly happy to see The Grandmaster at the New Beverly. “We shot this film on film,” said Wong, to the first of many bursts of applause. “This is the first time we show it on print. I would like to thank Harvey Weinstein personally for making this happen. It’s my first time to watch this film in 35 mm. With this audience, watermarks, secret codes — it really feels like a movie!” Added Le Sourd, “The projector’s doing something very nice for me: you see a little bit of flicker, the texture is beautiful.”

The New Beverly—which is underwritten by Tarantino and instigated a famous “Save 35mm” petition a few years back—is an ideal home for the 35mm unveiling of The Grandmaster, but it’s beyond sad that Wong Kar-Wai (!) had to wait until this screening to see his own film in his preferred format. Does a 35mm screening now require clearance from no less than Harvey Weinstein himself? (The same Harvey Weinstein, I might add, who nearly consigned Gray’s apparently breathtaking The Immigrant to VOD purgatory after a handful of DCP festival screenings.)

Ultimate Sight. Ultimate Sound.

A little over a decade ago, Jonathan Rosenbaum published a collection polemically titled Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Movies We Can See. At that time, Rosenbaum’s primary example of corporate curtailment of screen freedom was Harvey Weinstein (again!) conspiratorially buying up art house films (Through the Olive Trees, Dead Man, Young Girls of Rochefort, etc.) and then dumping them in a handful of theaters or refusing to release them at all. If the specifics are dated, the broader question — to what extent are our innocent viewing choices dictated by submerged corporate prerogatives? — certainly is not. Consumer choice is most visibly limited in the 35mm vs. DCP dust-up, but it’s hardly the only case.

In some instances, the choice presented is either false or actively muddied. The introduction of DCP was supposed to level the playing field for theaters everywhere, granting a single-screen in Peoria the same claim to a flawless presentation as “America’s Multiplex,” the AMC Empire 25.

In reality, chains are still trying to differentiate their product, even when the distinctions are minimal. Reviews and honest-to-goodness layman’s word-of-mouth insisted that Gravity had to be seen in 3D (preferably IMAX 3D) or not at all. The hype was enormously successful, with some 80% of ticket-buyers opting to catch Cuaron’s experiential outer space survival drama in 3D—an all-time record. (These days, a typical 3D release commands a stereoscopic share closer to 40%.) IMAX 3D screenings carry a super-premium ticket price, but to what end? The giant screen colossus, which once offered a genuinely unique 70mm dual-strip stereoscopic experience, now utilizes 2K DCP just like almost every other system, often shoehorned onto merely large-ish multiplex screens. (The post-production workflow for Gravity was wholly 2K, so conceivably the benefit from a better projection system would be blunted anyway.)

Yet even as IMAX actively tries to act like everybody else, everybody else keeps trying to ape IMAX. When I arrived at Regal City North for a Christmas Day screening of The Wolf of Wall Street I learned that the only auditorium showing the new Scorsese picture was RPX-equipped—the Regal Premium Experience, purporting to provide the super-charged, posh, perfect presentation that every paying customer has every right to expect from any theater in the first place. (AMC pushes a similar premium ETX brand and Muvico offers MUVIXL.) As DCP screenings go, Wolf of Wall Street looked fine and the RPX-monogramed seats were more expensive, if not necessarily more comfortable, than the multiplex standard—but the premium pricing provided little return.

Regal promises that RPX will be ‘the best movie experience available or your next movie is FREE.’ I wonder whether I would be granted a free ticket if I compared the Wolf of Wall Street show unfavorably to the Music Box’s 70mm screening of The Master back in February—a genuinely premium experience that was actually four dollars cheaper than the RPX matinee.

Make It a Blockbuster Night?

How much do ordinary moviegoers actually keep up on these marketing directives and corporate acronyms? Put another way, do these half-assed attempts to manufacture and massage demand actually create audience awareness?

In November the debauched rental juggernaut Blockbuster announced the imminent closure of its remaining non-franchise retail locations. The news surprised many—namely those who thought that Blockbuster had shuttered years earlier. Though the Internet eagerly commemorated Blockbuster’s demise with characteristic snark—and indeed, fate sometimes smiles even upon Blockbuster, as when a Hawaii outlet logged a DVD of This Is the End as the chain’s iconic last rental—few reckoned with the ball-busting scope of the video shop’s legacy. For years, the allegedly family-friendly chain dictated the outer limits of sexual expression in Hollywood cinema by refusing to stock NC-17-rated tapes—even while its shelves overflowed with truly prurient direct-to-video, purportedly erotic ‘thrillers.’ If a Hollywood film couldn’t be sold to Blockbuster down the line, it could scarcely be financed in the first place. (Were it not for Blockbuster, how many films would have followed in the transgressive footsteps of Showgirls and Crash?)

The Blockbuster legacy is also, of course, deeply strange. While on its last legs, Blockbuster sought any possible advantage over Netflix and Redbox. Consequently, Blockbuster entered exclusive rental agreements with the likes of the Weinstein Company (again!) and IFC, making everybody’s least favorite lowest-common-denominator chain the improbable DVD purveyor of such fare as Jacques Rivettes’s Ne touchez pas la hache, Gus van Sant’s Paranoid Park, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Le voyage du ballon rouge. Consider just how elastic, and ultimately meaningless, the Blockbuster brand was. Millions of millennials can recall the disarmingly breezy cadence of those long-ago TV ads imploring you to “Make It a Blockbuster Night”—but how many of them could even begin to define what a Blockbuster Night was? What did it mean and what did it have to do with anybody’s broader idea of The Movies?

The Blockbuster legacy is also, of course, deeply strange. While on its last legs, Blockbuster sought any possible advantage over Netflix and Redbox. Consequently, Blockbuster entered exclusive rental agreements with the likes of the Weinstein Company (again!) and IFC, making everybody’s least favorite lowest-common-denominator chain the improbable DVD purveyor of such fare as Jacques Rivettes’s Ne touchez pas la hache, Gus van Sant’s Paranoid Park, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Le voyage du ballon rouge. Consider just how elastic, and ultimately meaningless, the Blockbuster brand was. Millions of millennials can recall the disarmingly breezy cadence of those long-ago TV ads imploring you to “Make It a Blockbuster Night”—but how many of them could even begin to define what a Blockbuster Night was? What did it mean and what did it have to do with anybody’s broader idea of The Movies?

Sadly, Blockbuster conquered America but never aspired to be anything but a bland behemoth. Ubiquitous but chided by nearly everyone, Blockbuster couldn’t even claim culture wars relevance. Antipathy towards the brand never stoked the Red State-Blue State divide like Chick-fil-A or compactly symbolized suburban sameness like TGI Friday’s. Its market share was 3,000 miles wide, but its brand loyalty scarcely five inches deep.

Like many big box stores, Blockbuster shrewdly undercut local businesses everywhere, only to eventually collapse under its own weight, leaving communities across America with nothing. Not surprisingly, the few remaining video stores represent everything Blockbuster stood against: deep catalog, curated selection, flexible membership terms. Still, Scott Mendelson is not entirely wrong when he presents a contrarian defense of the Blockbuster:

For the moment, with rental DVDs on the verge of death and online streaming not yet caught up to it in terms of quality, we are stuck with an inferior delivery system which has supplanted a tried-and-true delivery system for the medium we call “home video”.

I mourn not for the giant corporation known as Blockbuster Video, but rather for the product known as “DVD rental” that is quickly becoming an endangered species. Those of you who prefer consumer choice and quality above convenience should mourn as well.

Doubtless, this argument sounds familiar to many 35mm partisans.

Doubtless, this argument sounds familiar to many 35mm partisans.

The Object Itself

Celluloid enthusiasts and DVD viewers have historically come out on opposite sides when debating fundamental questions about cinema, such as “35mm—Ineffable Beauty or Anachronistic Scratch-Magnet?” or “Communal Moviegoing—Invaluable Experience or Brat-Infested Popcorn Pit?” Still, they should be prepared to co-exist as strange bedfellows for the foreseeable future, equally invested in the unfashionable perpetuation of physical media.

One needn’t be a luddite to recognize the advantages of movies held in your hand rather than on someone else’s cloud. Netflix customers who’ve weaned themselves from DVDs and Blu-rays shouldn’t be surprised to see streaming titles regularly vanish without explanation. Several prominent titles, including Top Gun and Titanic, disappeared from Netflix as 2013 drew to a close, the inevitable consequence of licensing contracts coming up for renewal after Hollywood belatedly recognized just how lucrative streaming rights could be.

In related news, Amazon customers learned that digital movie files that they had purchased outright were, in fact, subject to withdrawal and recall at any time at the sole discretion of the licensor. Wisconsin dad Bill Jackson received a surprising amount of press coverage following his frustrated attempt to stream a Disney holiday special that he had already bought from the online Goliath. Jackson commented:

I don’t think you can buy digital content at this time. I don’t think it’s possible. There may be a button that says buy now, but that does not exist. It’s a rental. Any promise that it’s going to be there forever, it’s only good as long as the company exists and decides it’s OK.

Even Blu-ray consumers are making a trade-off: video and audio quality are much better than DVD, but key disc features (even, in extreme cases, the ability to play the movie in the first place!) are dependent on constant firmware updates. Supplemental material that once lived in perpetuity on disc is now available only through a broadband connection and the ongoing benevolence of the studio. Region coding, which could be easily circumvented on DVD, is more robust (though hardly insurmountable) for the high-def disc. Collectors just want to own copies of their favorite movies and the industry is slowly nudging them away from that paradigm.

Of course, film collectors are familiar with this attitude. Though studios regularly leased and sold 16mm prints to private customers as late as the 1940s, film collecting as such has been an illegal, clandestine hobby for the past few decades. These prints remain studio property, leased to theater owners for a specific contract term, and anybody else who has them must have stolen them. In Hollywood, it’s flat-out theft, even if the print was rescued from a dumpster or silver reclamation facility, even if the studio doesn’t give a damn about some old movie that nobody wants to see anyway.

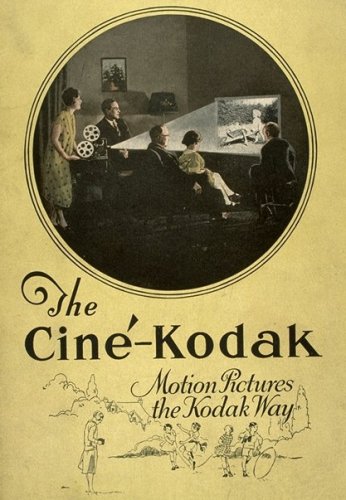

This stance has softened somewhat in recent years, since private collectors often possess unique copies of films that would otherwise be lost. (Almost every extant silent era Universal title, for example, owes its salvation to private collectors who retained 16mm Universal Show-at-Home prints after the 35mm originals were lost or destroyed.) Still, any archive hoping to receive a proper chain of provenance for an incoming film collection should adjust expectations accordingly. Memories of FBI raids in the 1970s still sting for a certain generation of film collectors, and the justifiable paranoia born from that unfortunate era will never dissipate.

This stance has softened somewhat in recent years, since private collectors often possess unique copies of films that would otherwise be lost. (Almost every extant silent era Universal title, for example, owes its salvation to private collectors who retained 16mm Universal Show-at-Home prints after the 35mm originals were lost or destroyed.) Still, any archive hoping to receive a proper chain of provenance for an incoming film collection should adjust expectations accordingly. Memories of FBI raids in the 1970s still sting for a certain generation of film collectors, and the justifiable paranoia born from that unfortunate era will never dissipate.

We’ve speculated before that the final home of 35mm and 16mm may well be not the theater or the museum, but the basement screening room. Our friend Peter Conheim, who operates one such underground venue in the Bay Area, was recently profiled by a quizzical KQED reporter. The whole article is very much worth your time, but one passage stands out:

When I ask Conheim if there’s a Honus Wagner card of film prints, he names the British Star Wars, processed in Technicolor. It doesn’t fade, he says. “They were still using that process in England up to 1977 or so. Those are really sought after, because even the original negative has faded.” A Technicolor print of Vertigo is also valuable. “I saw one sell for $10,000 two or three years ago. I’ve never seen a Star Wars British version for sale. I know two people who have them. One guy is so freaked out it’s going to be a disappointment he’s never opened the box it came in. I’ve been standing in front of the box with him many times, he’s like, ‘I’ll get there.'”

Whether it’s RPX or IMAX, it’s impossible to imagine a digital file with such intimidating aura and history.