In the short history of the Northwest Chicago Film Society, we’ve faced some formidable challenges. In our first season, a 16mm print of Silver Lode was lost in transit. In our second season, one of the Portage Theater’s 35mm projectors fell off its pedestal right before a show of Comanche Station. And of course, back in May we found ourselves locked out of the Portage with no advance notice, collateral damage in the new landlord’s curious scorched earth campaign against his own theater. These kinds of obstacles are familiar enough for any film exhibitor or small business owner: logistics problems, equipment malfunctions, property disputes.

In the short history of the Northwest Chicago Film Society, we’ve faced some formidable challenges. In our first season, a 16mm print of Silver Lode was lost in transit. In our second season, one of the Portage Theater’s 35mm projectors fell off its pedestal right before a show of Comanche Station. And of course, back in May we found ourselves locked out of the Portage with no advance notice, collateral damage in the new landlord’s curious scorched earth campaign against his own theater. These kinds of obstacles are familiar enough for any film exhibitor or small business owner: logistics problems, equipment malfunctions, property disputes.

But there’s another looming problem that’s definitely out of the ordinary: the ongoing shutdown of the federal government.

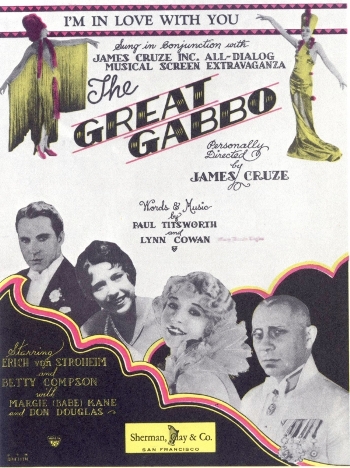

Like many of the world’s film societies, museums, and cinematheques, we regularly borrow 35mm prints from the Moving Image, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. If you’ve enjoyed our screenings of So’s Your Old Man, High Treason, Heat Lightning, or The Great Gabbo, you really have the Library of Congress to thank. They conserved, preserved, and circulated all of these titles, as well as Joseph Losey’s M, which we plan to screen on November 6.

The Film Society is hardly the only venue in this boat. Across town, Doc Films at the University of Chicago has a Library print of All Quiet on the Western Front booked for Oct. 29. The AFI Silver in Silver Spring, Maryland is supposed to screen Native Son on Oct. 26 and 29. The Library’s new print of the indie exploitation/protest film I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany is slated to run at MoMA’s renowned ‘To Save and Project’ preservation festival on Oct. 26. The Wisconsin Cinematheque has announced The Crowd Roars for Nov. 9. (An Oct. 4 screening of the same film has already been canceled by the North Carolina Museum of Art.)

Of course, all of these shows—including our M screening—may still happen, but based on recent developments, the speedy resumption of government services looks increasingly unlikely. The work of the Library of Congress is one of the many government services deemed inessential, and thus suspended until Congress approves a continuing resolution to reopen and fund the federal government. Access to the thousands of digitized treasures on the Library of Congress web portal, inaccessible for the first few days of the shutdown, has largely been restored, but the site still carries this message: “Due to the temporary shutdown of the federal government, all Library buildings are closed, all public events are canceled, and all inquiries and requests to the Library of Congress web-based services will not be received or responded to until the shutdown ends.”

Of course, all of these shows—including our M screening—may still happen, but based on recent developments, the speedy resumption of government services looks increasingly unlikely. The work of the Library of Congress is one of the many government services deemed inessential, and thus suspended until Congress approves a continuing resolution to reopen and fund the federal government. Access to the thousands of digitized treasures on the Library of Congress web portal, inaccessible for the first few days of the shutdown, has largely been restored, but the site still carries this message: “Due to the temporary shutdown of the federal government, all Library buildings are closed, all public events are canceled, and all inquiries and requests to the Library of Congress web-based services will not be received or responded to until the shutdown ends.”

A single screening of M is obviously is a miniscule part of this larger paralysis. Whatever inconvenience this represents for the Film Society is absolutely nothing compared to the 800,000 federal employees denied a regular paycheck and perhaps even backpay. We might lose a few bucks, which is trivial when set next to the real economic damage provoked by this needless shutdown: decimated buying power for federal workers, uncertainty for government contractors, threats of eviction and foreclosure.

We plead not for special treatment, but expansive context. This episode merits discussion because of the misleading impulse to treat the shutdown as an abstraction in faraway Washington, a routine political skirmish that might affect some faceless bureaucrats but barely touches the everyday lives of regular American citizens. In fact, the work of the federal government is so diverse and wide-ranging that many of us don’t necessarily recognize the myriad small ways that this work undergirds our cultural landscape.

A relative handful might be denied the chance to see this 35mm print of M and that fact may not travel very far outside film circles. That’s the point: we often move in cloistered subcultures, unable to connect isolated events to a broader picture. There are surely thousands of comparable cancelations, delays, and disruptions directly arising from the shutdown—visible to specialists but below the radar of the general public. There’s potent symbolic value in images of veterans denied access to monuments consecrated in their honor, but we needn’t pretend that they constitute the only offensive residue of the shutdown. Public sites like parks illustrate the stakes, but what about public objects?

• • •

The Library of Congress is fairly unique among film archives. Its collection grew in fits and starts, its preservation activities haphazard. Unlike so many peers, it is not marked by the legacy of a visionary curator like the Museum of Modern Art’s Iris Barry, the George Eastman House’s James Card, the Cinémathèque francaise’s Henri Langlois, or the Belgian Cinémathèque Royale’s Jacques Ledoux. To say that the Library of Congress arose from a bureaucratic, almost accidental, vision is not a criticism.

The Library of Congress is fairly unique among film archives. Its collection grew in fits and starts, its preservation activities haphazard. Unlike so many peers, it is not marked by the legacy of a visionary curator like the Museum of Modern Art’s Iris Barry, the George Eastman House’s James Card, the Cinémathèque francaise’s Henri Langlois, or the Belgian Cinémathèque Royale’s Jacques Ledoux. To say that the Library of Congress arose from a bureaucratic, almost accidental, vision is not a criticism.

Movies did not receive official recognition as a form subject to copyright until 1912. Before that date, producers who wanted to avail themselves of this legal protection had to commit a queer, medium-effacing fiction: registering their motion pictures with the Library’s Copyright Office as a series of successive still photographs printed to rolls of paper. Ironically, the Library of Congress is probably the first film archive built on a foundation of non-filmic materials.

This requirement eventually changed, of course, but its implications are still rippling through the Library. Patrick Loughney, who currently heads the Packard Campus complex in Culpeper, Virginia, which houses the Library’s film archive, aptly described the importance of this legacy when interviewed for Kino’s Edison DVD box set nearly a decade ago:

One of the important things about [the paper print collection] is that it’s a randomly acquired collection of motion pictures. In other words, it’s a selection of motion pictures. While not complete in its documentation of all the films that were produced or distributed in America, it is a collection that was self-selected. These were films that were acquired for rather anonymous legal purposes. They were not chosen by a curator. They were not chosen by a later generation to supposedly document the important films of an era or the films that documented the history of cinematic art. The importance of that is that they represent both the mundane and the important types of films being produced . . . . They were never looked on as motion pictures. They were looked on as legal records in the archives of the Copyright Office.

Crucially, this ethos never exactly left the Library. Their ecumenical collection, arising as it does from the practical, value-neutral copyright process and robust efforts to plug in gaps, is very strange and wide-ranging. It includes everything from the latest blockbuster and the Warner Bros. nitrate materials (donated when the studio saw no lasting value in its old negatives) to independent efforts and forgotten silent features.

The Library’s preservation efforts, which have been in operation almost continuously since the late 1960s, are similarly catholic. They’ve restored the long-neglected ‘silent’ version of Best Picture honoree All Quiet on the Western Front, the ribald, uncensored cut of Baby Face, and provocatively marginal fare like Lash of the Penitentes, a bit of mid-’30s religious exploitation ballyhoo that plays like junkyard Tarkovsky. They’ve resurrected films that literally shift the borders of American film history, like the Argentine ex-pat version of Native Son starring Richard Wright, or The Flying Ace, the silent aviation melodrama with an all-African-American cast, or one third of a nation …, an interesting screen version of the famous ‘Living Newspaper’ that arose from the WPA Theater Project.

Joseph Losey’s M is a perfect illustration of the necessity of the Library of Congress. An American remake of one of the towering masterpieces of world cinema, this is the kind of film that many will automatically underrate as a simple curiosity, a footnote. Produced independently and leased on a short-term basis to a major studio that had no financial incentive to retain its negative or perform expensive preservation work down the road, M fell through the cracks. There’s a well-worn former release print in the collection of the British Film Institute and it’s circulated some (it was shown in Madison this past April), but an American film deserves a place in an American archive. M is not an orphan film, exactly: after Columbia’s theatrical run, the rights reverted to producer Seymour Nebenzal and those rights have been passed down to his son, Harold Nebenzal, now 91. Who but the Library of Congress would have the resources and the resolve to create a new 35mm print of this film? (It’s moving, too, to contemplate the fate of director Joseph Losey: once hounded out of his own country for his Communist sympathies, now his films are preserved by the federal government.)

Joseph Losey’s M is a perfect illustration of the necessity of the Library of Congress. An American remake of one of the towering masterpieces of world cinema, this is the kind of film that many will automatically underrate as a simple curiosity, a footnote. Produced independently and leased on a short-term basis to a major studio that had no financial incentive to retain its negative or perform expensive preservation work down the road, M fell through the cracks. There’s a well-worn former release print in the collection of the British Film Institute and it’s circulated some (it was shown in Madison this past April), but an American film deserves a place in an American archive. M is not an orphan film, exactly: after Columbia’s theatrical run, the rights reverted to producer Seymour Nebenzal and those rights have been passed down to his son, Harold Nebenzal, now 91. Who but the Library of Congress would have the resources and the resolve to create a new 35mm print of this film? (It’s moving, too, to contemplate the fate of director Joseph Losey: once hounded out of his own country for his Communist sympathies, now his films are preserved by the federal government.)

The future of the Library of the Congress, post-shutdown, is equally important to our film heritage. With the demand for photochemical work shrinking and commercial film labs closing, the Library’s in-house film laboratory will become increasingly important. Along with the lab run by UCLA, it may well be the facility of last resort in an increasingly digital world. This laboratory will necessarily operate in the public interest, preserving not only films but the craftwork that makes their preservation possible in the first place.

• • •

All of the arguments in the preceding section have power and legitimacy only because the films preserved by the Library of Congress are available for public viewing. One of the most important aspects of the Library of Congress’s film preservation program is the fact that it is a circulating collection. Prints deposited for copyright purposes cannot leave the Library and there are understandable restrictions upon the circulation of unique prints and flammable nitrate copies. But once a title has been properly preserved by the Library of Congress, a print can be borrowed by a venue with demonstrated film-handling expertise. The venue is responsible for shipping costs and clearing copyright with the appropriate rightsholder, but pays nothing to the Library of Congress. No access fee, no handling fee, no archival inspection fee. It is a free collection. (By comparison, private archives often charge an access fee ranging from $300 to $600 for a single screening, which is cost-prohibitive for some worthwhile venues.)

This is, of course, as it should be. These films are preserved largely through tax revenue and it is the public’s right to see them. Venues that screen these prints are effectively partners assuring the dissemination of our film heritage.

Beyond a doubt, the film preservation activities of the Library of Congress were immaterial to the political calculations surrounding the government shutdown. That its operations have been suspended is incidental to the purported objective of the shutdown—defunding, and thus dismantling, the Affordable Care Act. Nevertheless, the closure of the Library underlines an incidental and fundamental dividend of the shutdown: the decimation of public trust and public spiritedness.

The Library of Congress and its employees are in an especially precarious position. Silenced by the shutdown and never especially outspoken given the political dimensions of the Congressional appropriations process, these civil servants are effectively invisible in a debate that directly concerns their livelihood. It would be perverse to cancel a screening without emphasizing this fact.

As the organ of a non-profit cultural organization, it’s not the business of this blog to take partisan positions. But is it a partisan position to ask that officials elected to serve in the public interest acknowledge the very idea of public life?