Alfred Hitchcock frequently cited Sabotage as the film that forced him to refine his technique: suspense above all—or at least, up to a point. It was a mistake, he later reckoned, to mix suspense too closely with sentiment, to tighten the noose while remaining indifferent to the neck. In the film’s most (in)famous sequence, a bomb explodes on a London bus, the work of a terrorist who plants the device on an innocent boy. “I broke the rule,” Hitchcock said, “that the hero is always rescued from danger at the last minute … There were yowls of protest from everyone, especially the mothers.”

Alfred Hitchcock frequently cited Sabotage as the film that forced him to refine his technique: suspense above all—or at least, up to a point. It was a mistake, he later reckoned, to mix suspense too closely with sentiment, to tighten the noose while remaining indifferent to the neck. In the film’s most (in)famous sequence, a bomb explodes on a London bus, the work of a terrorist who plants the device on an innocent boy. “I broke the rule,” Hitchcock said, “that the hero is always rescued from danger at the last minute … There were yowls of protest from everyone, especially the mothers.”

This fatal indifference is actually crucial to the effectiveness of Sabotage, which possesses a straight-ahead ruthlessness that Hitchcock’s other British films generally lack. There’s no time for music hall routines or local color here. Not that Sabotage lacks for black humor. All this bus hubbub unfortunately overshadows a wicked irony embroidered into the script; when the boy climbs up to the bus, the operator stops him and informs him that he cannot bring two reels of nitrate film onboard. It’s flammable, after all.

Perhaps only a sadist could chuckle at this moment—the nitrate film is actually the least dangerous thing on the bus, but acknowledging that requires a smirking premonition of annihilation.

Quentin Tarantino borrowed this moment unexpectedly in Inglourious Basterds—a succinct, stern illustration of the vintage film stock’s absolute danger before propelling his cockeyed blow-up-the-Nazis-with-nitrate plot forward. Certainly Tarantino is not the first to exploit nitrate film’s volatile chemistry. In the 1970s and 1980s, film archivists expressed the urgency of their cause by circulating photographs of the ravages of vault fires and advancing the catchy slogan ‘Nitrate Won’t Wait.’ In 2002, the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) published a heavy tome dedicated to the antiquated film stock—This Film Is Dangerous, a sexy spin on a frequently unsexy profession.

Quentin Tarantino borrowed this moment unexpectedly in Inglourious Basterds—a succinct, stern illustration of the vintage film stock’s absolute danger before propelling his cockeyed blow-up-the-Nazis-with-nitrate plot forward. Certainly Tarantino is not the first to exploit nitrate film’s volatile chemistry. In the 1970s and 1980s, film archivists expressed the urgency of their cause by circulating photographs of the ravages of vault fires and advancing the catchy slogan ‘Nitrate Won’t Wait.’ In 2002, the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) published a heavy tome dedicated to the antiquated film stock—This Film Is Dangerous, a sexy spin on a frequently unsexy profession.

How dangerous was nitrate film, really, and why did a young industry settle upon such an irresponsible standard?

Gasoline, Pine Shavings, and Nitrate of Cellulose

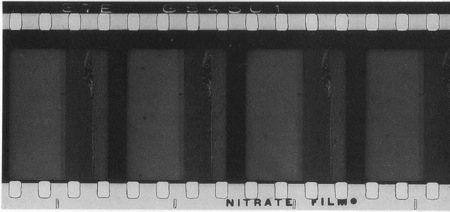

A strip of film consists of two basic layers—the emulsion and the base. The emulsion is the thin, photo-sensitive layer which carries the image and the soundtrack. The base, which comprises about 98% of the film strip’s thickness, is essentially a support backing; its chemical composition contributes nearly nothing to the exposure and development of the image or track. But the chemical makeup of the base is crucial for other reasons, namely the pliability, utility, durability, and longevity of the film. The nitrate base—in continuous, near-exclusive use for 35mm film from 1895 to roughly 1950—happened to be both very robust and very flammable.

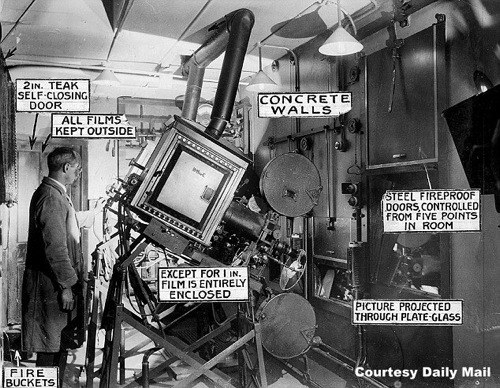

The fact that nitrate film could start a severe, self-oxidizing fire when exposed to open flame was not exactly obscure. Nor was such exposure unfathomable: to fill a screen, film had to pass before a very hot light source in the projector. In our age of ubiquitous liability and malpractice litigation, building a business upon such knowledge seems about as rational as decorating a candlemaker’s shop with oily rags.

This was not a hypothetical concern. Nitrate fires, while infrequent relative to the wide and rapid diffusion of cinema, could be rather spectacular. One such fire at Paris’s 1897 Charity Bazaar famously claimed 126 lives. (Since burning nitrate produces its own oxygen, even submerging a flaming reel in a vat of water does little to quell the fire. A nitrate fire must burn itself out—which may take quite a while if a fire engulfs a projection booth with two dozen reels of film.)

This was not a hypothetical concern. Nitrate fires, while infrequent relative to the wide and rapid diffusion of cinema, could be rather spectacular. One such fire at Paris’s 1897 Charity Bazaar famously claimed 126 lives. (Since burning nitrate produces its own oxygen, even submerging a flaming reel in a vat of water does little to quell the fire. A nitrate fire must burn itself out—which may take quite a while if a fire engulfs a projection booth with two dozen reels of film.)

How could such a dangerous medium enjoy such a broad public life? One would expect the film industry to answer safety concerns with an invocation of professionalism. To return to our candlemaker analogy, it might be dangerous, in theory, to co-mingle flames and flammable material, but only if the amateur candlemaker made a mess of precision craftsmanship. A professional projectionist would never be clumsy as to ignite a reel of nitrate.

Remarkably, though, one detects a faintly blasé attitude toward nitrate within the industry. Motion Picture Theater Management, Harold B. Franklin’s book-length manual from 1928, alludes to the nitrate hazard as an afterthought: “Needless to say, smoking in the booth is strictly prohibited.” One industry apologist, C. Francis Jenkins of the Graphoscope Company, lamented nitrate’s bum rap in a 1920 issue of Educational Film Magazine:

The Post Office strictly refuses to accept dangerous substances for transportation in mail cars, but apparently does not consider motion picture film an extra hazard, for it handles about five hundred tons of it daily, and without mishap . . . .

Nitrate of cellulose motion picture film is not “highly inflammable,” in the sense that widely-used gasoline is, for example. It is not volatile, which is greatly in its favor. It will ignite easily and burn very rapidly when lying in a loose pile just as pine shavings will …. Motion picture film in its usual tightly rolled form cannot readily be ignited with a match; the match will almost invariably burn itself out before the film will blaze. Tightly rolled film is rather difficult to fire; therefore, all film should be handled in this form and kept so, in metal cans or similar containers.

Jenkins’s contrarian cheeriness soon rises to the level of awe-inspiring irresponsibility, or perhaps a Swiftian proposal. Read the following passage and remember that Jenkins is discouraging the use of fireproof projection booths in such non-theatrical venues as schools and churches:

Now as to the desirability of a booth, let me say that in no other human employment involving hazard is it contended that concealing the operator tends to added safety, makes him more careful. “More light on the subject” is always a good slogan. We illuminate dangerous places so that we may minimize the danger. We keep tab on the railroad engineer by a system of block signals. Why, we don’t trust a paid watchman, for we put a clock to watching the watchman. But when it comes to the picture projection risk, we require the operator to work concealed on the assumption that he will be more careful and more diligent in keeping film off the floor and in its metal container and that he will not smoke if he works unseen, even though he may be a cigarette fiend. The concealed booth is an anomaly, a reversal of time-honored safety practice.

We sense a theme here, no? Nitrate film doesn’t cause nitrate fires; cigarettes cause nitrate fires.

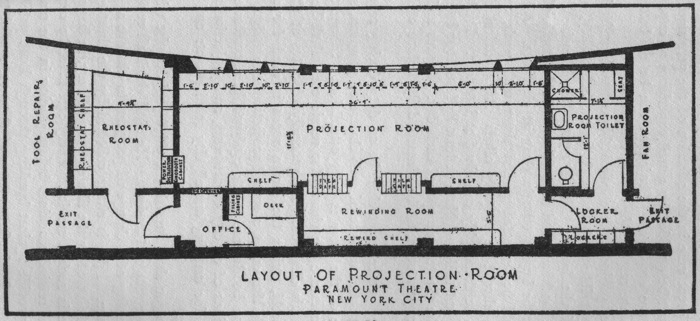

Unsurprisingly, the real militancy on the nitrate front came from the projectionists themselves, who were, after all, the likeliest to suffer the consequences of a flare-up. Often blaming fires on poor booth layout and inadequate union consultation in business matters, the projectionists made a compelling, if unsuccessful case. From an astonishing November 1936 issue of International Projectionist:

Unsurprisingly, the real militancy on the nitrate front came from the projectionists themselves, who were, after all, the likeliest to suffer the consequences of a flare-up. Often blaming fires on poor booth layout and inadequate union consultation in business matters, the projectionists made a compelling, if unsuccessful case. From an astonishing November 1936 issue of International Projectionist:

Five projectionists in as many widely scattered states of this otherwise glorious Union have died in projection booth fires during the past ninety days. Ninety divided by five is eighteen. Not a bad average, this—especially for an industry that prides itself on the comfort and peace and relaxation and opportunity for escape from dreary reality that it provides daily for the “masses” of this world.

Masses! The word somehow sticks in one’s mind. Maybe this industry of ours that disdains anything less than superlatives must have mass killings, due to its own delinquencies, before it comes out from behind the smoke screen of glamour and romance laid down by high-powered publicity and reveals its true raiment of false front and ballyhoo.

Mixed Media

Although Hollywood frequently downplayed the dangers of nitrate, they did not ignore research about non-flammable replacements. Assorted alternative bases were tested. Some were used in the non-theatrical market, but dubbed insufficiently durable for the usage and abusage of the daily grindhouse. It’s perhaps unfair to judge the sanity of nitrate projection by the prints that have come down to us, often enfeebled by age and adverse storage conditions. When nitrate prints were new and fresh from the lab, they proved quite robust and thus generally safe. Studios may have wanted to replace the flammable film with a less-lethal option, but not if it meant overhauling the infrastructure of distribution.

We must remember here that film prints had a very different lifespan in the pre-multiplex era. A film generally did not open simultaneously across the country, which would’ve signaled the distributor’s unease or desperation. A title might open at one major movie palace in downtown Chicago and then filter down to second-, third-, fourth-, even fifth-run neighborhood houses. In other words, prints traveled through many different booths over the course of their useful lives. Switching to an inferior non-flammable stock and regularly replacing prints mid-release would represent a major upset in the supply chain, as compared to the infrequent nuisance of nitrate fires.

We must remember here that film prints had a very different lifespan in the pre-multiplex era. A film generally did not open simultaneously across the country, which would’ve signaled the distributor’s unease or desperation. A title might open at one major movie palace in downtown Chicago and then filter down to second-, third-, fourth-, even fifth-run neighborhood houses. In other words, prints traveled through many different booths over the course of their useful lives. Switching to an inferior non-flammable stock and regularly replacing prints mid-release would represent a major upset in the supply chain, as compared to the infrequent nuisance of nitrate fires.

The early non-flam options, like diacetate, retain a strange power today. There is an indescribably special something that occurs when cracking open a can and discovering an old diacetate print. (More than one person I know has likened it to the smell of her grandmother’s house.) But it was the non-theatrical venues—churches, schools, libraries, campsites, private homes graced with Kodascope projectors—that handled these brittle diacetate prints, in all manner of gauges (35mm, 16mm, 28mm, etc.)

The theatrical venues had to wait until the early 1950s for a new, non-nitrate standard. Triacetate was finally dubbed sufficiently durable and the switch occurred with relatively little mainstream fanfare. One wonders how clean this transition really was, and how long old nitrate films sat around the print exchanges. On the production side, nitrate certainly did not vanish instantaneously. The negatives of An American in Paris, Native Son, and Saga of Anatahan were all assembled from a mix of nitrate and safety material. (Contra the “nitrate won’t wait” mantra, it’s the safety stock in these transitional negatives that often deteriorates first and thus bedevils preservationists.)

Non-Flam, Non-Fun?

Given the widely documented problems with nitrate and the totality of its eradication from the theatrical world, is it at all surprising that this “dangerous film” would later become enshrined as a fetish totem for cinephiles? Archivists and critics of a certain generation maintained that nitrate simply looked more lustrous, more silvery, more cinematic than its ho-hum, triacetate replacement.

Is this position gospel truth, rosy nostalgia, or something in between? Though black-and-white nitrate did possess greater silver content than triacetate, a base is still a base—it’s the emulsion where the image lives and dies, with the base acting largely as a carrier.

Even if nitrate itself possessed no inherent magic, the nitrate era saw generally excellent labwork—at least until World War II and its chemical rationing. Surviving nitrate release prints can be very impressive—but we must remember, too, that producers and labs often opted to make prints directly off the original, irreplaceable camera negative. (Intermediate stocks offered protection, but they were mediocre and consequently avoided as much as possible.) The camera negative might run through a contract printer hundreds of times before being retired, replaced, or simply trashed. All that remained were tattered prints, shoddy dupes, and indifferent intermediates produced as an afterthought—poor starting points for preservation and restoration.

Even if nitrate itself possessed no inherent magic, the nitrate era saw generally excellent labwork—at least until World War II and its chemical rationing. Surviving nitrate release prints can be very impressive—but we must remember, too, that producers and labs often opted to make prints directly off the original, irreplaceable camera negative. (Intermediate stocks offered protection, but they were mediocre and consequently avoided as much as possible.) The camera negative might run through a contract printer hundreds of times before being retired, replaced, or simply trashed. All that remained were tattered prints, shoddy dupes, and indifferent intermediates produced as an afterthought—poor starting points for preservation and restoration.

Such practices yielded mouth-watering first generation prints and murky junk for subsequent copies. To complain a new restoration of a nitrate-era film doesn’t hold up next to the original print is simultaneously accurate and ludicrous: the irresponsible, but widely accepted, practice of squeezing every last print out of the camera negative gilded the present at the expense of the future. Nitrate looked great—perhaps greater than audiences deserved.

Direct comparison is, in any case, difficult. While nitrate prints were screened somewhat regularly in museum situations throughout the 1970s, such occasions are quite rare today. In 2000, FIAF and the BFI bid nominally farewell to flammable film with a “Last Nitrate Picture Show” symposium. In America, there are only a handful of venues that advertise their ongoing nitrate activities: the Library of Congress, George Eastman House, UCLA, the Stanford Theatre, the American Cinematheque. (There are, of course, private collectors who still project nitrate in their own homes under the responsibility radar. One friend recalls a nitrate screening of, appropriately enough, the burning-of-Atlanta reel from Gone with the Wind in a collector’s basement.)

As nitrate-safe booths are a distinctly niche operation, there is insufficient critical mass for real certification and licensing. (What legal body would regulate less than a dozen nitrate aspirants?) It is a self-declared designation, a political gesture. To run nitrate responsibly means adopting a mosaic of antique safety precautions, complying with local fire regulations, and applying common sense. (No cigarettes.) At minimum, a nitrate booth should have fire shutters over all port windows, fire suppression accessories on the projector itself, fireproof film storage cabinets, and a policy of no less than two projectionists on duty during nitrate screenings.

Regardless of where one comes down on the nitrate question, it’s crucial that we support venues that continue this quixotic endeavor. We cannot pass judgment on nitrate until we really see it on screen.