The Lone Consensus

For box office watchers, last month’s failure of The Lone Ranger offered an opportunity for city slicker schadenfreude and quick-draw conclusions. Boasting a combined production and marketing cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $400 million, The Lone Ranger has no absolutely chance of turning a profit or kick-starting a new summer franchise. Nevertheless, its failure hardly imperils the future of its studio, as prior runaway productions like Cleopatra and Heaven’s Gate once threatened to do. Industry consensus says that Disney will simply take a nine-figure write-down and steer clear of committing that much money to an unproven brand again, at least for a while. (The same lesson was presumably learned last year in the wake of John Carter, but The Lone Ranger had already left the station.)

The real victim here is not Disney or Depp, but the future of the movie Western. Nearly every Ranger post mortem treated the genre as the primary culprit in the movie’s collapse and the self-evident reason that the production never should have gone before cameras in the first place. After outlining the Ranger’s disappointing performance relative to the $3.7 billion Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, Box Office Mojo’s Ray Subers conceded, “For the Western genre, The Lone Ranger did have a good opening; unfortunately, that’s a very, very low bar.” Deadline’s Nikki Finke noted that “it was always a risky bet since young moviegoers have largely stayed away from Westerns and have little familiarity with the masked man or his sidekick…. But big-budget Westerns Wild Wild West, Cowboys & Aliens, Jonah Hex all flopped.” (Nota bene: Hollywood will remember the lessons of Cowboys & Aliens long after real audiences forgot that the movie ever existed in the first place.)

The Hollywood Reporter sounded a somewhat more constructive note: “[W]e can but hope that the next time someone pitches a ‘can’t-lose’ take on a western for the summer blockbuster audience, someone remembers the fates that befell both Ranger and Wild Wild West — even Jonah Hex, for that matter — and asks the all-important question: ‘Does it have to be a western?’”

The coarsest assessment came from Indiewire’s Tom Bruggemann:

What were they thinking? With the only breakout Westerns in recent years — “True Grit” and director Gore Verbinski’s animated “Rango” — totalling about $250 million each worldwide, producer Jerry Bruckheimer and Disney gambled on spending that much–plus $150 million in worldwide marketing– on the runaway production “The Lone Ranger.”

The gross shows the problems with these high-cost films. Betting on Johnny Depp to provide the core appeal, they managed to draw perhaps six million paying customers (normally a decent showing) for a genre of uncertain domestic and even less assured foreign appeal, all in a film about a character best known to Medicare recipients …

Only the Los Angeles Times offered a half-hearted defense of the genre. Under the optimistic headline “Five must-see westerns beyond ‘The Lone Ranger,’” the company town’s paper-of-record trotted out a pre-release interview with Jeffrey Richardson of the Autry National Center of the American West. “The marketing might of Disney and Johnny Depp might make this a little different — hopefully ignite a passion of a much younger audience,” Richardson predicted.

Following the Ranger’s underwhelming release, the Times compiled a list of the ten highest-grossing Westerns, as if to prove that it could really name that many successful Westerns. (Thanks to media consolidation, thousands of young Chicagoans also learned about the Western’s box office virility in the pages of the RedEye while riding their horses to the office.) Yet another Times think-piece on the shaky future of the Western (which had proven strangely “resistant to the magic of special effects and huge exploding machinery”) advised prospective directors to “keep the budget low and the setting traditional. All that’s needed for a solid western, after all, is a few horses, a good script and a nice expanse of New Mexico or Alberta.”

Whither the Western?

How did a central idiom of American life and showbiz become such an automatic and unambiguous liability? Not withstanding imitation oaters like Cowboys & Aliens, Hollywood has produced only a handful of Westerns since the near-back-to-back Oscar triumphs of Dances with Wolves and Unforgiven. The major Westerns of the past two decades have trafficked in affectation and self-conscious distinction: the acid trip trajectory of Dead Man, the digitally-assisted wonderment of The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the feminist critique of Meek’s Cutoff, the period linguistics of True Grit. Of course, producing a Western in this day and age is automatically a gesture toward art, or at least something far removed from popular taste. (One middling, run-of-the-mill contemporary Western, Appaloosa, is the exception that proves the rule.)

It was not always so. More than any other genre, the Western provided a ready-made twentieth-century template for an evening’s unpretentious entertainment. Despite the success of big-budget efforts like The Covered Wagon, Cimarron, and Union Pacific, Western audiences were often content with unadorned costumes, unoriginal stories, and dirt sets. “My father went to a Western just about every night of his life that I remember,” wrote Pauline Kael in a 1967 issue of The New Republic. “He didn’t care if it was a good one or a bad one or if he’d seen it before. He said it didn’t matter … If you’re going for a Western (the same way you’d sit down to watch a television show), it doesn’t much matter which one you see.”

It was not always so. More than any other genre, the Western provided a ready-made twentieth-century template for an evening’s unpretentious entertainment. Despite the success of big-budget efforts like The Covered Wagon, Cimarron, and Union Pacific, Western audiences were often content with unadorned costumes, unoriginal stories, and dirt sets. “My father went to a Western just about every night of his life that I remember,” wrote Pauline Kael in a 1967 issue of The New Republic. “He didn’t care if it was a good one or a bad one or if he’d seen it before. He said it didn’t matter … If you’re going for a Western (the same way you’d sit down to watch a television show), it doesn’t much matter which one you see.”

The assembly-line indifference was more than just a critical construct—it was embedded in the very structure of Hollywood production. As Murray Ross noted in his 1941 Tinsel Town labor chronicle, Star and Strikes, the first contract won by the Writer’s Guild stipulated a $1,500 minimum for all feature film scripts—except Westerns, for which the minimum was set at $1,000.

Westerns were synonymous with American movies, but also stood resolutely apart from them. Incomprehensible to the Eastern money men who backed the studios and never taken very seriously by the West Coast creative personnel, Westerns occupied the same kiddie matinee ghetto as serials, cartoons, and jungle pictures.

The Western was the genre system writ large: so long as the movie claimed a minimum of familiar signposts, that was sufficient. (Most every great Western boasts some appreciation of the tactile landscape but, ironically, the geographic specificity is the least essential element. A Western need not be laid in the West. There’s a distinctly Northeastern, French-Canadian flavor to The Big Sky and Django Unchained is a Southern plantation yarn, yet both are obviously Westerns. Any frontier will do.)

Nevertheless, the Western also invited a sort of macho connoisseurship. The strain of moralistic, dirt-drenched realism represented by Hell’s Hinges, Hell’s Heroes, Day of the Outlaw, and High Plains Drifter was set against the jokey surfaces of a Destry Rides Again or a Cat Ballou. A comedy-Western was a contradiction in terms—or, more directly, a Western pitched to people who “don’t really like Westerns” (i.e., Easterners, women, liberal urbanites, etc.).

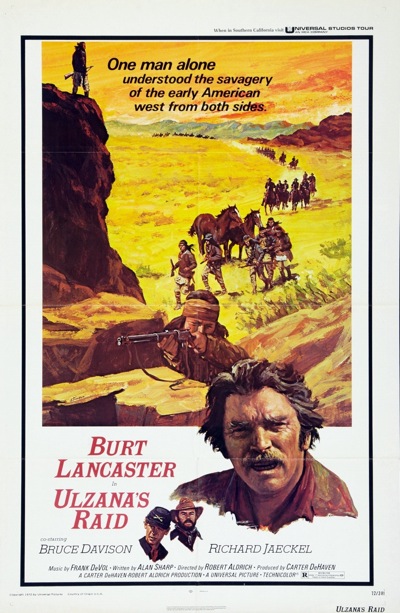

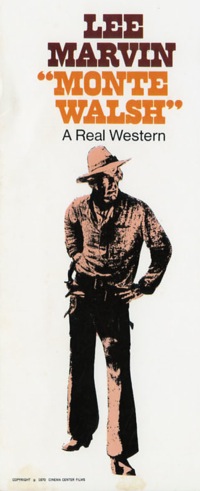

After Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid—a sentimental, Burt Bacharach-scored, pretty boy adventure yarn disguised as a Western—broke all box-office records for the genre, Western aficionados launched a grim counter-offensive that would last well into the 1970s. In the aftermath of “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head,” Cinema Center Films released Monte Walsh with the cryptically terse tagline “A Real Western.” (None of that hippie stuff, see?) Though many Vietnam-era efforts were described as revisionist Westerns or anti-Westerns in their day, they now look plainly like Westerns, full-stop. They might poke fun at John Ford’s affection for “Shall We Gather at the River” or tweak American history, but the ’70s twilight wave—which includes such disparate films as McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Culpepper Cattle Co., Ulzana’s Raid, The Shootist, and the blood-soaked corpus of Sam Peckinpah—clearly derives its power from the ongoing validity and vitality of the Western form. Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, the film from the period that truly explodes the genre, uses the Western as a metaphor for Hollywood’s rape of Latin America.

After Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid—a sentimental, Burt Bacharach-scored, pretty boy adventure yarn disguised as a Western—broke all box-office records for the genre, Western aficionados launched a grim counter-offensive that would last well into the 1970s. In the aftermath of “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head,” Cinema Center Films released Monte Walsh with the cryptically terse tagline “A Real Western.” (None of that hippie stuff, see?) Though many Vietnam-era efforts were described as revisionist Westerns or anti-Westerns in their day, they now look plainly like Westerns, full-stop. They might poke fun at John Ford’s affection for “Shall We Gather at the River” or tweak American history, but the ’70s twilight wave—which includes such disparate films as McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Culpepper Cattle Co., Ulzana’s Raid, The Shootist, and the blood-soaked corpus of Sam Peckinpah—clearly derives its power from the ongoing validity and vitality of the Western form. Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, the film from the period that truly explodes the genre, uses the Western as a metaphor for Hollywood’s rape of Latin America.

The Indian Question

As J. Hoberman has noted, the Western has always been “heavy, heavy, heavy on content.” With its explicit historical dimension, its frequent dramatization of the lives of real frontiersmen (and occasionally, women), and its rough-riding law ‘n’ order dramatic throughline, the Western is uniquely positioned to address real questions about the shape and character of American society. In any other genre, civic dimensions and political interpretations are frequently met with critical resistance—it’s “reading too much into the film,” or “imposing your ideology” on harmless entertainment. But the raw materials of the Western are inherently political: gun rights, land rights, property disputes, ethnic strife, restraint and regulation of trade, law enforcement, military maneuvering, war and peace.

The Western, then, is not really defined by quick-draw showdowns or horse riding feats or white hats vs. black hats set-ups. Instead, it functions as the quintessential pop form for working through the American experience.

In a film like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the social dimensions are made literal: the democratic promise of the frontier classroom and the small-town newspaper, the primitive power of violence normalized through the grown-up channels of acclamation and election, the referendum on statehood taming the cactus flowers of the prairie. But it doesn’t play like a civics lesson or a liberal lecture—it arises naturally from the form itself.

The most radical strand of the Western deals aggressively and openly with questions of race. Indeed, many of the most incendiary and politically daring films of the Civil Rights era are Westerns, almost invariably set around the Civil War and Reconstruction. By projecting contemporary conflict back a century into the past, these Westerns could raise questions that other movies avoided. Samuel Fuller’s Run of the Arrow and Don Siegel’s Flaming Star cajole audiences to contemplate an appropriate response to the state-sanctioned white supremacy and come down, with caveats, on the side of armed resistance. What did audiences in 1960 think when Elvis Presley, the most popular personality in America, joins the Kiowa and vows to eradicate his white neighbors? (Predicting a box-office bonanza, Variety summed up the freighted appeal of the film as follows: “Flaming Star has Indians-on-the-warpath for the youngsters, Elvis Presley for the teenagers and socio-psychological ramifications for adults who prefer a mild dose of sage in their sagebrushers.”)

The Civil War/Civil Rights Western stretched to all corners of the industry and all flavors of the genre and favored a slippery parity among all oppressed minorities. John Ford’s Sergeant Rutledge uses the Western set-up to ask whether a black man could receive a fair trial for the rape of a white woman. Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles, unfairly remembered solely for its juvenile campfire farting contest, turns the familiar new-sheriff-in-town premise into a satire of suburban white flight anxieties. Even The Scavengers, Lee Frost’s “roughie” sexploitation Wild Bunch rip-off, pits unreconstructed Confederate pillagers against largely sympathetic black separatists. (Such was the spirit of ’69—social upheaval felt everywhere, even among the raincoat brigade of the local grindhouse.) This long-dormant cycle obviously culminates with Django Unchained, with interracial audiences cheering for the righteous destruction of a white (capitalist) empire.

The Civil War/Civil Rights Western stretched to all corners of the industry and all flavors of the genre and favored a slippery parity among all oppressed minorities. John Ford’s Sergeant Rutledge uses the Western set-up to ask whether a black man could receive a fair trial for the rape of a white woman. Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles, unfairly remembered solely for its juvenile campfire farting contest, turns the familiar new-sheriff-in-town premise into a satire of suburban white flight anxieties. Even The Scavengers, Lee Frost’s “roughie” sexploitation Wild Bunch rip-off, pits unreconstructed Confederate pillagers against largely sympathetic black separatists. (Such was the spirit of ’69—social upheaval felt everywhere, even among the raincoat brigade of the local grindhouse.) This long-dormant cycle obviously culminates with Django Unchained, with interracial audiences cheering for the righteous destruction of a white (capitalist) empire.

In other words, the Western boasts a rich, suggestive, and quite heterogeneous history, far larger than the box-office implosion of The Lone Ranger—or Heaven’s Gate, for that matter. Nothing has yet emerged as full-blown, civic-minded pop art successor to the Western, either. (Perhaps the similarly “content-heavy” Star Trek comes closest.) One senses that we need one. Shall we gather at the river?