Early on in my career as a film exhibitor, I fielded a straightforward and slightly irate question from an audience member. The night before, my college had screened a rare Maurice Tourneur film in a soft, middling 16mm print, which we had advertised, correctly, as an ‘archival print.’ Shouldn’t an archival print look better than that, he wondered? Shouldn’t it look, if not wonderful, at least good?

The answer I fear I gave this man, tautological but also correct, was that an archival print simply meant a print obtained from an archive.

Archival prints are special, but if programmers hope to train audiences to salivate at the mere words, they have another thing coming. The fact that a print can be described as archival doesn’t necessarily translate into a more luminous or detailed image, a scratch-free print, or, for that matter, a better movie. In truth, the real distinction comes down to the fact that the programmer probably had to negotiate for the right to screen the print, document the venue’s film handling workflow, attest to a sterling record with borrowing similar artifacts for peer institutions, and sign an intimidating loan agreement. This compared to the relatively simple process of booking a film from a studio or an indie distributor, which can often be accomplished with a simple phone call. It’s an inside-baseball commendation, a process-oriented triumph whispered about by fellow connoisseurs.

Of course, the division between a standard print and an archive print grows blurrier every week. Though obtaining a print from a laidback, local 35mm exchange was never quite as simple as ordering a sandwich, the days of lax print management are definitely over. With the future of raw stock and quality laboratory work highly uncertain, no one can afford to be clumsy with prints, even if the industry as a whole would prefer that prints simply go away. Every studio has its own archival division, which is now often the only source for titles that were available for the general market a decade or two ago. And if the studios’ archival divisions don’t have a loanable copy of a given title, the programmer must turn to a non-profit archive, such as UCLA or MoMA, in hopes of finding a suitable surrogate

Another irony: many archival prints—each reel thoroughly inspected after every screening, with each frame rigorously counted and checked and then returned to an environmentally stable can—began their lives as ho-hum distribution prints. Before coming to the archive, they were spliced and diced, repeatedly built up and broken down, covered in aluminum foil and zebra tape, projected dozens or hundreds of times, and shipped across the country in rusty, old cans. Archives exist to produce new prints from painstaking restorations, but they’re also repositories of abused and abandoned artifacts.

Career projectionists often scoff at this admittedly artificial decree. “Why can’t I splice the heads and tails on this print?” he asks. “It’s been cut so many times before, but now it’s ‘archival,’ apparently.” (Bonus points awarded when the projectionist recalls cutting this exact print back in its pre-archival innocence.)

But ultimately, the artifice is the point. The rules may be thoroughly silly, but the existence and enforcement of a framework is wholly necessary. The archive is the best, last, only resort of posterity.

But ultimately, the artifice is the point. The rules may be thoroughly silly, but the existence and enforcement of a framework is wholly necessary. The archive is the best, last, only resort of posterity.

In his recent, widely-circulated piece on the history of cinema in the New York Review of Books, Martin Scorsese sounded an optimistic note about the forward evolution of film preservation:

For the first few decades of cinema, preservation wasn’t even discussed—it was something that happened by accident. Some of the most celebrated movies were the victims of their own popularity. In certain cases, every time they were rereleased, the prints were made from their original negatives, and in the process those negatives became degraded, hardly usable.

It wasn’t so long ago that nitrate films were melted down just for the silver content. Prints of films made in the 1970s and 1980s were recycled to make guitar picks and plastic heels for shoes.

As far as I know, I’ve never bought a pair of shoes made from films bits (though there’s obviously a hitherto-untapped hipster market here), but the casual destruction of prints continues apace. It was by no means restricted to an earlier, less enlightened time. In the last few years, I’ve personally witnessed film prints being fed through a paper shredder (none too successfully, I might add) and film prints being pierced and maimed with an electric drill.

Why destroy a print in the first place? Because the rights have expired. Because it’s not being rented often enough. Because warehouses have to be consolidated. Because there’s a new vice president at the helm and he just wants all those prints gone by lunch, goddammit, and don’t ask any questions!

Why destroy a print in the first place? Because the rights have expired. Because it’s not being rented often enough. Because warehouses have to be consolidated. Because there’s a new vice president at the helm and he just wants all those prints gone by lunch, goddammit, and don’t ask any questions!

More charitably, the economics of film production always assumed a high degree of turnover, waste, and reuse. A popular film demands hundreds or thousands of prints to meet audience demand and maximize profit in the first few months of release. As demand erodes, it’s logical to downsize supply. No sane business would pay for the indefinite storage of two thousand unrented prints. Just keep a few prints around to meet the needs of the second-run circuit or the college market or the repertory cinema clientele. But how many prints is enough? Twenty? Ten? One?

An unpopular title might get rented once a year and a single print might serve that demand perfectly well—but what if it gets lost in transit or destroyed by an indifferent projectionist? What then?

The calculus has become even stranger in the shadow of the digital conversion. Prints can’t be loaned out because they’re too valuable—but if they can’t be loaned out and realize a profit, why pay to store them in the first place?

There are many, many talented and passionate people working in the studio archival divisions. But the continued existence of film prints is precarious—the equilibrium could be upended by one activist shareholder or an executive shuffle or a new dictate from the parent company.

What about the private collector? Long a de facto protector of films discarded or disowned by their rightful owners, the film collector faces challenges of her own. After a lifetime’s investment of money and effort, what does she have to show for it? A house full of film prints—furniture sagging, projection port holes cut out of walls and bookcases, a vinegar scent that reaches far beyond the kitchen. With many fellow collectors selling off prints and switching to DVD or Blu-ray (or books or family), how long will it be until the collection becomes totally worthless? No one wants to be the last film collector. One collector we know (and from whom we’ve borrowed prints) informed us this week that he was getting out of the film racket for good.

If this sounds like a grim prognosis, listen up: the secret strength of the archive, its useful burden, comes down to the fact that it can’t discard its collection on a whim. An archival acquisition is a contract, a promise to keep an artifact for the term of its natural life. It may be neglected, it may be in deep storage, it may remain invisible to the public, but it won’t be thrown in the garbage or turned into a guitar pick. (Up in arms about all the wonderful films ‘locked away’ from public view in an archive? Be part of the solution by organizing a screening and borrowing a print.)

Yes, archives can discard objects, but through a lengthy process of deaccessioning, often requiring the highest level of board approval. This unconscious maintenance regime outlives fashion and outlasts a curator’s idiosyncratic prejudices. In time, I suspect, all prints will be archival prints.

Yes, archives can discard objects, but through a lengthy process of deaccessioning, often requiring the highest level of board approval. This unconscious maintenance regime outlives fashion and outlasts a curator’s idiosyncratic prejudices. In time, I suspect, all prints will be archival prints.

The archival print is also more than a wise insurance policy; it’s also a living record of the people who cared for it.

It’s easy enough to look at a restoration from four decades ago and scoff at the results. Some might react that way to Swing High, Swing Low tonight. It was restored in the early 1970s after the AFI discovered that neither its original studio (Paramount), nor the studio that bought the rights to the underlying story material (Twentieth Century-Fox) had a complete copy of the film. Three reels were missing from Paramount’s 35mm nitrate copy, which were eventually supplemented with blow-up footage from Mitchell Leisen’s personal 16mm print, which the director had willed to a friend.

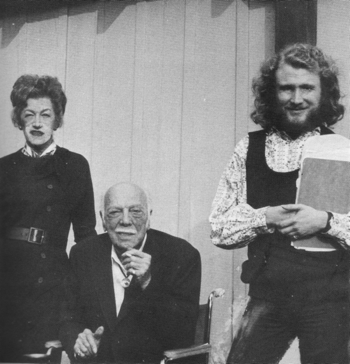

In his essential book on the filmmaker, Mitchell Leisen: Hollywood Director, David Chierichetti recounts viewing this very 16mm print with his buddies Leonard Maltin and Mae Woods, and an aged, emphysema-ridden Leisen shortly before his death. In one of the book’s most extraordinary photographs, we see a twentyish, long-haired Chierichetti appearing onstage with Leisen and his mistress Natalie Visart, both bitter and brittle. That faded Hollywood glamour should be resurrected by a hippie oral historian is one of the lovely, unheralded happenings in cinema.

Perhaps a better print of Swing High, Swing Low could be made today, but would the improvements obscure this story? This observation applies to many, many archival prints aside from Swing High, Swing Low. Digital tools provide many exciting restoration opportunities,  but they ultimately cannot return what no longer exists. The limitations of the past remain stubbornly present. Some scratches are built in to the preservation materials, the lost-lost original negatives copied at a time when wetgate technology (which seamlessly fills in the scratches embedded in the film base during printing) simply did not exist. Optical printing has improved tremendously over the last few decades, but many older restorations produced by this method look soft to us today. (The softness represented a fair trade-off at the time; conventional contact printing would have yielded a sharper, but less stable, image.) When a film survives only in stark, contrasty dupe copies, digital tools cannot resurrect a mouth-watering greyscale.

but they ultimately cannot return what no longer exists. The limitations of the past remain stubbornly present. Some scratches are built in to the preservation materials, the lost-lost original negatives copied at a time when wetgate technology (which seamlessly fills in the scratches embedded in the film base during printing) simply did not exist. Optical printing has improved tremendously over the last few decades, but many older restorations produced by this method look soft to us today. (The softness represented a fair trade-off at the time; conventional contact printing would have yielded a sharper, but less stable, image.) When a film survives only in stark, contrasty dupe copies, digital tools cannot resurrect a mouth-watering greyscale.

One more story: I once saw a horrible, decades-old archival print of Phil Jutzi’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, cobbled together from multiple, damaged sources, some subtitled, some not. The subtitled reels (in Finnish?) had been hastily treated in the lab, the unwanted titles obscured with a crude optical trick that left a prominent shadow across a third of the screen. The interpolations and the enforced uniformity left visible scars on the film, including appalling contrast fluctuations. Who made these choices and who signed off on them?

Yet this, too, was a restoration—and represented a disarmingly human dimension of effort and determination. Someone worked very hard just to get this print to look as bad as it did. What possessed someone to do it? I was appalled and impossibly moved.