Macho Criticism (From the Seat of His Pants)

Macho Criticism (From the Seat of His Pants)

Last week WBEZ’s Alison Cuddy interviewed our Executive Director Becca Hall about ‘Chicago’s stunning lack of female film critics and abundance of female film programmers.’ This disparity should be readily apparent and familiar to any sentient person, but its roots and effects merit further discussion.

For better or worse, the dialogue undergirding film culture, here and elsewhere, is usually set by men. It’s something that you can feel acutely when reading a rave review of Nicolas Winding Refn’s hateful exercises in macho posturing or watching the contrived critic’s roundtable on the Pulp Fiction Blu-ray. (In the latter, Stephanie Zacharek provides a voice of reasoned dissent as the middle-aged boys club recites their favorite quotable moments from Tarantino’s anal anxiety breakthrough.) When critics try to address these issues head on, they often make matters worse, as when Mike D’Angelo stuck a blow against “robotic objectivity” in a recent Cannes dispatch. D’Angelo proudly attributed his preference for Blue is the Warmest Color over Behind the Candelabra to the fact that he’s “a straight male who’s indifferent to guy-on-guy action but had to keep adjusting his pants during the lesbian picture.”

The world of film critics (and film enthusiasts generally) suffers for its gender imbalance, much like related subcultures like record collecting. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle, where the insular atmosphere discourages many women from participating in the first place.

The American cinema we tend to take seriously is littered with failed fathers and stunted men—the intergenerational post-Method clashes of Paul Thomas Anderson, the slacker gravitas of Judd Apatow, the brittle patriarchs of Wes Anderson, the horny, sad bravado of Alexander Payne, the daddy longing of Steven Spielberg. Reach back further and we find the elegiac machismo of Sam Peckinpah, the ‘cinema fist’ of Samuel Fuller, the breezy camaraderie of John Sturges and Howard Hawks. These are valid subjects for cinema, but are they the only subject? We celebrate films that mourn masculinity, rather than challenge it.

Of course, the vocabulary of auteurism (prevalent in the previous paragraph and elsewhere) almost preordains this result. Women have historically been severely underrepresented in the director’s chair and focusing on films in auteur terms necessarily suggests a stable of personal themes and concerns issuing exclusively from a single (male) ego. So long as we choose to talk about films in terms of directors instead of actors or other behind-the-scenes technicians, we’re privileging one kind of contribution over another. And with a handful of fascinating exceptions (Lois Weber, Ida Lupino, Shirley Clarke, Kelly Reichardt, among others), it’s a very uneven playing field.

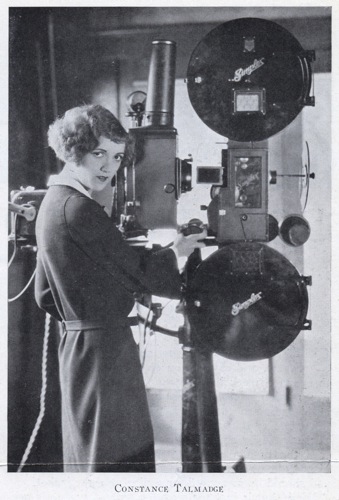

It should be noted that Hollywood has employed women as screenwriters and editors with much greater frequency and consistency. Women also won many important below-the-line craft positions in laboratories and studio vaults early on. In an undated fan magazine column, Constance Talmadge advised aspiring actresses to ditch dreams of silver screen fame and focus on stable movieland employment:

The laboratory of every big studio employs scores of young women. Many of the girls get good pay as “splicers.” Other girls “break down” old negatives and positives, prints which they classify under various heads such as “war scenes,” “auto smashups,” “fire scenes,” and the like. These girls also have charge of the film vaults, housing these valuable bits of film which are used in new pictures, for “atmosphere”!

Other laboratory girls run the printers which make positive films from the original negatives. This is well paid, technical work. Other young women are employed in the “soup rooms,” where the film is developed in solutions. The drying drums in many studios are looked after by girls. The sorting and assembling of the various scenes in a production also is done in many cases by young women.

When the film is assembled and the various scenes spliced together in a consecutive reel, there comes the important work of cutting the picture. The girl who has developed a sense of “tempo,” who knows how to give the proper length to each scene and its relation to the picture as a whole, who knows what scenes to leave full lengthy and which to “snap up” — such a clever girl soon gains a reputation as “a good cutter,” and her salary begins to mount.

Admittedly, it’s difficult to imagine a criticism that revolves around these often anonymous contributions. It would be systematic and process-based, economic rather than artistic. (Consider the parallel rise of the “China Girl,” who wound up on the film, but not on the screen.)

But does the failure of criticism stem from the questions being asked or from those doing the asking? Chicago undeniably does have a dearth of female critics, especially when compared to other media markets—Stephanie Zacharek at the Village Voice, Manohla Dargis at the New York Times, Betsy Sharkey at the Los Angeles Times, Carrie Rickey at the Philadelphia Inquirer, Marjorie Baumgarten at the Austin Chronicle.

These critics write for (notionally) print publications and therein lies the issue. Perhaps it’s more accurate to describe the decline of film critics generally rather than female critics specifically. It’s true that there are no female film critics writing for TimeOut Chicago, but the recent capricious dismantling of that publication doesn’t leave much space for any bylines, male or female. We aren’t doing enough to support aspiring women critics, but why would anyone choose this vocation these days? Professional, salaried gigs for film critics are drying up. The conversation continues, but is an unpaid capsule on Cine-File a patch on a column in the Sun Times? (Of course, Cine-File does publish fine criticism, much of it from women, including Shealey Wallace and the prolific Kat Keish. Disclosure: I also publish occasionally on Cine-File, too.)

What Makes a Programmer?

Cuddy reports wildly different outcomes for female programmers, but I don’t share this optimism. From where I sit, the divide nationwide is decidedly more lop-sided than 50-50. Look, for example, at the repertory film programmers’ symposium published by Cineaste in 2010: lengthy responses from fourteen top programmers, thirteen of them men. (The magazine published a substantially different version online.) For what it’s worth, twelve of the fourteen were based on the East Coast, with no representation accorded to the vibrant film cultures of Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, or Austin. And as Cuddy points out, film programming has an equally sorry record on racial diversity.

As with criticism, questions about programming ultimately revolve around definitions of professionalism. At many prestigious institutions, the curator who writes catalog essays and introduces films and hobnobs with donors is a man, while the assistant who does the heavy lifting (booking prints, coordinating shipping, managing front-of-house operations) is just as often a woman. In a just world, they would both be counted as programmers, but job titles infrequently reflect a different understanding. (There are, of course, notable exceptions, among them Mimi Brody at Block Cinema, Peggy Parsons at the National Gallery of Art, and Susan Oxtoby and Kathy Geritz at the Pacific Film Archive.)

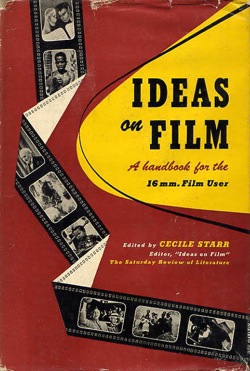

The blogosphere has recently democratized and flattened film criticism, but the world of film programming has always operated in a grey area between hobby and vocation. One of the great film books, Ideas on Film, presents this lesson starkly. Published in 1951, when scarcely anyone was employed full-time as a film programmer, we get programming tips on non-theatrical subjects from labor organizers, librarians, college instructors, public health officials, and film society coordinators. Pearl S. Buck even offered advice gleaned from her amateur involvement in the Green Hills Farm Film Council. (Need I even mention that the expansively democratic Ideas on Film was, of course, edited by a woman—Cecile Starr, who contributed a weekly 16mm column for the Saturday Review of Literature.)

The blogosphere has recently democratized and flattened film criticism, but the world of film programming has always operated in a grey area between hobby and vocation. One of the great film books, Ideas on Film, presents this lesson starkly. Published in 1951, when scarcely anyone was employed full-time as a film programmer, we get programming tips on non-theatrical subjects from labor organizers, librarians, college instructors, public health officials, and film society coordinators. Pearl S. Buck even offered advice gleaned from her amateur involvement in the Green Hills Farm Film Council. (Need I even mention that the expansively democratic Ideas on Film was, of course, edited by a woman—Cecile Starr, who contributed a weekly 16mm column for the Saturday Review of Literature.)

The questions raised by Ideas on Film are no less relevant today. Put bluntly, many outstanding programmers perform this work out of sheer amateur tenacity—i.e., without compensation. Few are drawing salaries from microcinemas and film societies. Does a female programmer have parity with a male one if he gets paid and she doesn’t? What if programming is his sole responsibility while she programs films on the side, or as one duty among twenty others? Men may dominate the cinematheque ledgers, but many of the people who organize the (far more numerous) lower-profile, community-oriented screenings—nurses, school teachers, hotel entertainment coordinators, neighborhood leaders, PTA presidents, county bureaucrats—are women. Are they any less worthy of being called programmers?

Can a Girl Inspect Motion Picture Film?

Of course, as Cuddy notes, Chicago is also notable in its uncommonly high share of female projectionists. People who have never worked in the field probably have only a vague mental image of the typical projectionist. Booth veterans can provide a profile in ten seconds: ‘the old-timer’ or the ‘union projectionist’ instantly invokes a slightly overweight man with a slightly receding hairline, more talkative than most people but somewhat less personable. He refers to every movie as ‘the show’ (as in, ‘What’s the show you’re running in theater two?’) and makes uncomfortably off-color jokes while threading his machine and gets away with it because he can’t remember a lady in the booth since 1975. (He consecrates this private space with centerfolds and nudie pin-ups tacked up over the rewind bench.) He has shelves of used oil cans and lubricants and his skin is always dry and cracked. (Of course, the old school projectionist of lore could also fix absolutely anything with a paper clip and a length of twine, like a greasier version of MacGyver.) Simply stated, female projectionists have historically been an anomaly.

In fact, many issues surrounding exhibition have been highly gendered for decades. Consider the industry’s switch from 1000 ft. standard reels to 2000 ft. reels in the mid-1930s. Distributors and audiences complained of ‘film mutilation,’ and the blame was laid squarely at the (male) projectionists, who were charged with clumsily building up two or three 1000 ft. reels to reduce the number of manual change-overs they would perform over the course of a show. The studios responded by shifting the responsibility for splicing smaller reels together to the exchanges. These local, short-term warehouses handled the final leg of a complex system of national print distribution. They were also staffed almost entirely by women. Naturally, projectionists blamed print issues on lax inspection at the exchanges.

One largely sympathetic story in the March 1937 issue of International Projectionist outlined the conflict:

Can a girl inspect 2,240,000 frames of motion picture film every day for six consecutive days? Can the same girl be forced to work a few extra evenings, and possibly part of a Sunday, within the same week? Is the type of worker obtainable for these long hours for as little as $15 salary a week qualified for this important work? ….

It was established that there were no set hours of work. Each girl is given a certain minimum quota of reels to inspect per day … Thus the girl inspectors face each day not a certain number of hours of work but an irreducible minimum film footage! … This is what the exchanges term “inspection.” What any fair-minded person, knowing the delicate balance of projector mechanism and the degree of heat to which these prints are subsequently subjected, would term this process is probably unprintable in a publication sent through the mails.

To be fair to the exchanges, I’ve also heard of couriers refer to the classic octagonal film cases as ‘bowling balls,’ boasting of rolling them off the end of the dock back to warehouse floor. So the causes for film damage are various.

Chicago’s unusually high number of female projectionists has a number of interrelated explanations. Since the spectacular self-immolation of IATSE Local 110 roughly a decade ago, the barrier for entry for new projectionists, male and female, has been fairly low. The University of Chicago and, to a lesser extent, Northwestern University provide ample opportunities for students to learn basic projection skills, which are increasingly appealing in a stagnant post-graduation economy. And the work of James Bond has invested projection with an artisanal potential—it’s something that Chicagoans want to do and want to do well.

The City That Works

Of course, the non-trivial flip side of this abundance of non-union specialty labor is low wages for projectionists at many venues. With the demise of film at the multiplex, professional projectionists will soon be harder to find, but the economic value of their labor will not rise until audiences acknowledge the importance of these skills and demand quality presentation.

Am I arguing here for the primacy of class identity over gender? Certainly not. Rather, these issues are inter-related and cannot be addressed singly. The lack of professional opportunities exacerbates the gender gap and the homogeneity of voices weakens the economic power of the film community.

Ultimately, what makes Chicago unique, I think, is that all these professional distinctions are particularly difficult to tease out. Less cutthroat than several other cinema ecosystems, the key truth about Chicago’s film community is that there’s so little meaningful or easily identifiable division between critics and programmers, projectionists and audience members. The lines between institutions are porous. Critics such as Fred Camper have organized series under the auspices of the School of the Art Institute and local projectionists like Chloe and Douglas McLaren frequently write up shows presented by ‘rival’ venues for Cine-File. Programmers moonlight as projectionists, film distributors write criticism, filmmakers coordinate screenings, and archivists make critical arguments through their selections. In its own way, too, the Film Society hopes to complicate and integrate these activities, making its patrons and readers privy to challenges that face programmers and archivists. An audience better informed about the technical aspects of projection is a better-informed audience, period.

Of course, self-congratulation does not magically redress gender imbalance. Ultimately, it’s up to everyone to recognize that the constriction or outright absence of women’s voices substantially diminishes the quality, vibrancy, and truth of the conversation. Sexism hurts everyone, including men. Organizing a series or preserving a film or offering a critique—all of these acts are basically about enacting a vision of society. That vision needs to address the society we actually live in and the people who make it up.

Becca Hall, Katherine Greenleaf, Kat Keish, and Ben Kenigsberg contributed substantial critique and discussion. Neil Cooper and Joshua Romphf provided research assistance.