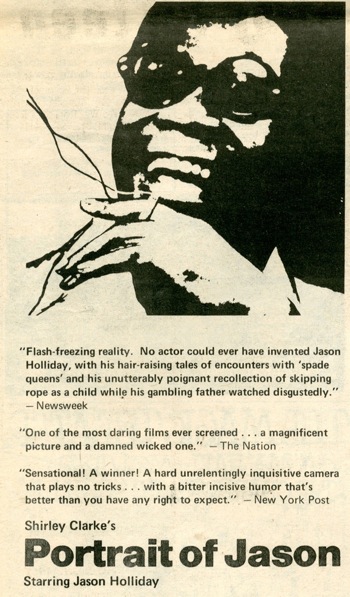

When Portrait of Jason opened in 1967, there were no LGBT film festivals. Major newspapers and respectable citizens referred to gays and lesbians in appallingly derogatory language. Civil rights pioneer Bayard Rustin had been shunted to the sidelines by Adam Clayton Powell, for fear that this homosexuality would undermine the movement. To be black and gay meant a life on the margin of the margins.

When Portrait of Jason opened in 1967, there were no LGBT film festivals. Major newspapers and respectable citizens referred to gays and lesbians in appallingly derogatory language. Civil rights pioneer Bayard Rustin had been shunted to the sidelines by Adam Clayton Powell, for fear that this homosexuality would undermine the movement. To be black and gay meant a life on the margin of the margins.

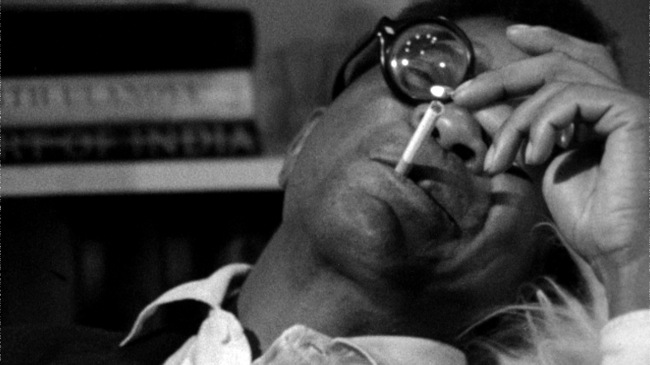

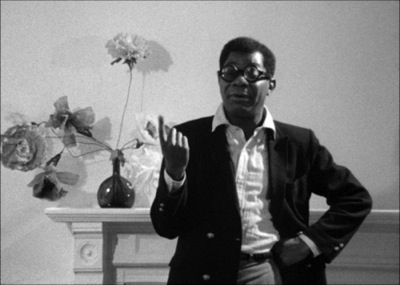

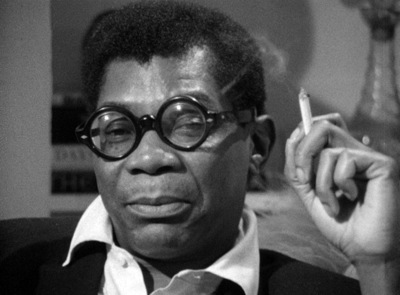

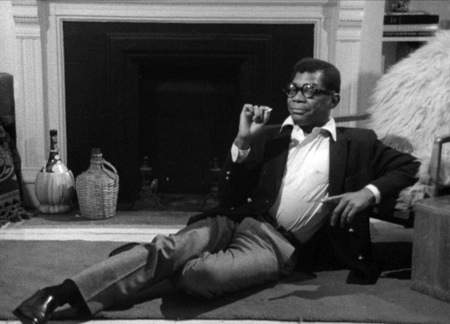

And here was Jason Holliday talking for nearly two hours about his brave, bawdy life before the camera.

There was some precedent for Portrait of Jason in Andy Warhol’s flurry of talkies, particularly the Ron Tavel-scripted Fire Island gabfest My Hustler. Warhol also made film portraits of uncomfortable intensity—Edie Sedgwick going about her daily business in The Poor Little Rich Girl, for example.

The debt to Warhol is economic and logistical, not just aesthetic. The unprecedented mainstream interest in Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls strained the passive distribution capacity of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, which booked mostly college showings and underground establishments. To break into first-run theaters coast-to-coast, Jonas Mekas, Shirley Clarke, and Louis Brigante created the more commercially-minded Film-Makers Distribution Center. Portrait of Jason would be handled by the new FMDC, a potential cross-over hit in an era when Hollywood had largely missed recent upheavals in American taste. Holliday even cut a comedy LP.

Unfortunately, Jason had no such luck. It had an unprofitable run in New York and received uneven play in other cities. The Chicago premiere was quietly hosted by Lake Forest College, as part of ‘Soul Week ’68: An Exploration into Afro-American Culture.’

Since the ’60s, Portrait of Jason has maintained a complicated, subterranean reputation. Reel Change, a 1979 guidebook to social issue-oriented films on 16mm, offered a mixed verdict:

Jason is a thirty-three year old black, gay male prostitute. In PORTRAIT OF JASON he dramatizes, with unusual candor, his life experiences of exploitation as a black man and nightclub performer and the discrimination he suffers because he is gay. Interviewed for almost two hours, Jason’s act before the camera is sometimes comic, other times cynical and bizarre. The film does not suggest solutions. However, through Jason’s stories and routines emerges a sense of the tragic realities suffered by many people as a result of racial prejudice and sexual preference. Awareness group and public show material.

“An absorbing revelation of the life of a man who is doubly rejected: as a black and as a gay … should be screened but with discussion or a positive image/action film.” (gays rights activist, San Francisco)

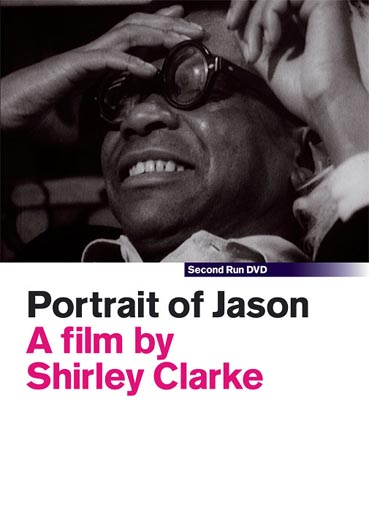

S ince the 1980s, Portrait of Jason has been difficult to see. A rarely-circulated 35mm preservation print from the Museum of Modern Art was last shown in Chicago in 2006 at the University of Chicago Film Studies Center as part of Ron Gregg’s Postwar Queer Underground Cinema screening series. The MoMA print subsequently served as the basis of a mediocre DVD released by the British label Second Run, now out-of-print.

ince the 1980s, Portrait of Jason has been difficult to see. A rarely-circulated 35mm preservation print from the Museum of Modern Art was last shown in Chicago in 2006 at the University of Chicago Film Studies Center as part of Ron Gregg’s Postwar Queer Underground Cinema screening series. The MoMA print subsequently served as the basis of a mediocre DVD released by the British label Second Run, now out-of-print.

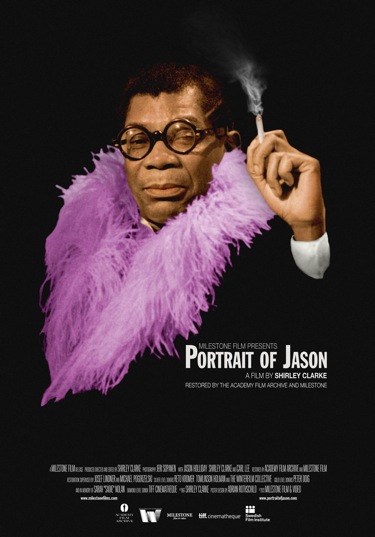

Portrait of Jason returns to Chicago thanks to the tireless work of Dennis Doros, co-owner of Milestone Films. Over the last few years, Dennis and his partner Amy Heller have re-released the features of Shirley Clarke under the Project Shirley banner. They’ve already put out The Connection and Ornette: Made in America, but Portrait of Jason posed a unique problem.

Doros felt that MoMA print was a good start, but could be improved. His extraordinary account of the search for the best surviving materials—which ultimately led to an unpromising “work print” in the archive of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research—must be heard to be believed. The restoration, produced in conjunction with the Academy Film Archive and with the support of a Kickstarter campaign, will be making its Chicago premiere on Wednesday at the Music Box Theatre. The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening a brand-new 35mm print, literally delivered straight from the lab.

I’ve booked prints from and talked films with Dennis for nearly a decade. I count him as a friend, as well as a major supporter of 35mm preservation when most outfits are abandoning film altogether. I spoke with him last week about the still-contentious questions posed by Portrait of Jason and the travails of the restoration process.

• • •

KW: I’ve read a lot about your efforts with Project Shirley, but I’m curious: I don’t think I’ve ever read how you first encountered Clarke’s work.

DD: I had known about her films for years. Let me be honest, I have to think about this, but it might have been after we started the Project, embarrassingly enough. Perhaps I bought the DVD of Portrait of Jason beforehand when I first thought of it, before we had acquired it. I started watching the films and realized that we needed to do it, that they were important films that weren’t easily seen and weren’t in good condition. As we progressed, I became more and more familiar with the films. I’m still watching quite a few of them.

KW: That’s almost appropriate in a way. If the whole mission of Milestone is to resurrect films that were difficult or impossible to see, you’re talking about a case where you hadn’t even seen them.

DD: It’s sometimes the case, not as often, but it was in this case. It did surprise me, because I was in New York in the ’80s. She was around. Amy knew her through being Dan Talbot’s assistant at New Yorker Films, but we really didn’t see the films until we thought about doing the Project.

KW: How did it come to your attention?

DD: People keep asking me how it got started and the answer is very simple and very long-winded. The simplest part is, we just thought about it. I turned to Amy and said, “What do you think about Shirley Clarke?” She said, “Great idea,” and we went from there.

DD: People keep asking me how it got started and the answer is very simple and very long-winded. The simplest part is, we just thought about it. I turned to Amy and said, “What do you think about Shirley Clarke?” She said, “Great idea,” and we went from there.

The long version is that ever since Killer of Sheep, we’ve been considering post-war American independent films. We’ve been reading books and interviews. Watched a lot of films. We’ve been thinking about these directors’ testing of boundaries between fiction and non-fiction.

KW: I know that Killer of Sheep was an enormous success for Milestone [in its 2007 theatrical reissue], but was there anything else that led you to reorient Milestone towards resurrecting works like On the Bowery, The Exiles, and Portrait of Jason?

DD: We’ve always been known for doing a lot of different kinds of films. From doing I Am Cuba to the Mitchell and Kenyon films to Piccadilly from England in 1929. We’ve been all over the map with classic films. We’re still doing a lot of stuff from different periods.

This body of ’60s and ’70s work from American independent filmmakers, it was also political, it was also social. It let people view the world differently than they had thought before they had seen that film. When they walked into the theater, they didn’t know that their minds were going to be changed or that they were going to see something different by the end of the film. That’s something that really is exciting for us and what we find important–ever since I saw The Sorrow and the Pity in college, where I was completely affected by that film. These films met that kind of test.

KW: What does Shirley Clarke’s work show us that we haven’t seen before?

DD: Oh, so many things. It’s like Melissa Anderson wrote about Jason in the Village Voice, this film “says more about race, class, and sexuality than just about any movie before or since.” Really, she nailed it on the head. This is a film from 1967 when being gay was illegal, before the civil rights reached its fruition in many ways. It’s just as relevant today while telling us so much more about a past that many people never knew existed.

We had a screening up in Harlem before Portrait of Jason opened at the IFC Center in New York. We worked with Imagenation, who promote films of African American content in Harlem. It was an incredible experience. They found this to be an extremely important film—they still know [people like] Jason today, on the borders of society. Still trying to get work, still trying to be accepted in society. They found it an amazing experience and a very moving experience. From screening to screening, from person to person, it will affect you in a different way.

KW: Jason Holliday was at the fringes of culture in 1967, but he still would be in 2013 in some ways. This is a story about civil rights, about gay rights, but it’s not p.c. He’s not a poster boy most organizations would care to claim or adopt.

KW: Jason Holliday was at the fringes of culture in 1967, but he still would be in 2013 in some ways. This is a story about civil rights, about gay rights, but it’s not p.c. He’s not a poster boy most organizations would care to claim or adopt.

DD: What they talked about in Harlem was that there were still 16-, 17-, 18-year-old Jasons still in New York, still having a difficult time fitting in to society. They saw this as an incredible educational tool, that it was still part of the American fabric of these people being on the fringes, not knowing where to go, not being white, not being straight.

KW: Shirley Clarke tried to get theatrical distribution for Portrait of Jason, but it mostly wound up getting shown on the college lecture circuit. Have you heard of it being used in a community-organizing context?

DD: I have not found any screenings like that. A lot of her screenings were college-oriented. It wasn’t doing what we did, having a screening in Harlem for the community. Back then, I would have loved for her to try that. I don’t know if distributors did that [outreach] in the 1960s.

KW: There’s also a sense in which these questions—Is Shirley Clarke addressing a white audience or a black audience? Is she addressing an audience of Jasons or an audience that’s slumming by listening in on his life—are part of the tension in the film itself. All of these questions about whether she’s exploiting him or giving him a spotlight or something in between are embedded in the very way that the film works.

DD: She was concerned about that while was editing it. She knew what she was doing. She put herself and Carl [Lee] into the film to show that there was this tension, there was this possibility of exploitation. She had a fascination with African American culture and that’s central to the film. How could you identify without being part of it? Carl was her entrance into the African-American community, of course.

She was not afraid of looking bad in her films. She was not afraid of portraying herself in a bad light. She was pretty self-knowledgeable. Four or five years into our Project Shirley, I’m still finding out new things about her, different facets of her that are sometimes upsetting and sometimes just amazingly wonderful.

KW: Let’s talk about the restoration a bit. You’ve been very forthright in acknowledging that this is the second time there’s been a restoration of Portrait of Jason. The Museum of Modern Art preserved it from less-than-ideal materials about ten or fifteen years ago. It’s actually a fairly instructive story about restoration, where you’re always using the materials at hand and hoping that someone is going to come along and improve upon it later.

KW: Let’s talk about the restoration a bit. You’ve been very forthright in acknowledging that this is the second time there’s been a restoration of Portrait of Jason. The Museum of Modern Art preserved it from less-than-ideal materials about ten or fifteen years ago. It’s actually a fairly instructive story about restoration, where you’re always using the materials at hand and hoping that someone is going to come along and improve upon it later.

DD: I purposely wanted to tell the whole story. MoMA did everything right. They thought they had the last 35mm print in existence and they preserved it to the best of their abilities. They took it to Cinema Arts in Pennsylvania, which is one of the most recognized archival labs in the country.

At the same time, there was another print in Sweden. They did not check the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. I would say that’s because there are so many films to be saved, so much work to be done, that no one except the amateur archivist has three years to devote to this kind of search. Kevin Brownlow certainly has shown that with Napoleon. There are many people—Paul Killiam, Raymond Rohauer, even—that have done this kind of work in the past. Archives have done this as well, but they don’t usually have the luxury of time because they’re salaried.

KW: There’s also a way that a restoration like MoMA’s, even if we now recognize it as a stop-gap, was important. It served as the source of the British DVD and that allowed people to see it. It allowed you to see it. It allowed it to circulate and still remain recognized even as the original materials were hiding in Wisconsin.

DD: This is absolutely the case. Archives sometimes will restore a film that has been already been restored by somebody else. There needs to be a continued conversation among archives—that’s what the Association of Moving Image Archivists is for, that’s what the International Federation of Film Archives is for. Continue the collaborations, continue the conversation between archives, find the materials to help each other. I hope that’s what my lecture about Portrait of Jason, which I’ve been taking all over the country, has been doing for students. There is this need for conversation.

KW: In the case of Portrait of Jason, as you’ve pointed out, the way Clarke edited the film fooled everyone for decades. Everyone thought that the original materials were nothing but outtakes.

DD: Even the original inspection reports said work print, but it also said outtakes. [A work print is a rough cut assembled and revised shot-by-shot by the filmmaker during the editing process. The work print guides the conformation of the original negative, but since it’s often spliced over and over again during post-production, the work print is rarely used for preservation projects. – KW] No one really considered this as source material because even if it was a work print, it was an early one and no one thinks of a work print as master material. I can’t say that this is a lesson in life, because I don’t know if this will ever be replicated. I have to say that even though I was correct, I was lucky. This was not something that was easily deduced. It was a shot in the dark. It was my last shot, really, before I gave up and went back to the MoMA restoration.

Really, the main lesson is that the papers—the letters, the correspondence—led me to consider this print again. You need to look at everything, including the papers, when you’re restoring a film. It gives you background, it helps you understand the film better. When you restore a film, you might have a letter where the director says something was printed too light back in 1928 or it ran too fast in 1924. The paper collections are just as important as the film material is.

KW: We’re talking about an area where the question of what a restoration aims to do is relevant. Is it what the filmmaker wanted the film to be or what audiences saw?

KW: We’re talking about an area where the question of what a restoration aims to do is relevant. Is it what the filmmaker wanted the film to be or what audiences saw?

DD: There were decisions to be made and we wanted to bring it back to September 1967. There are so many flaws in the printing from [original laboratory] DuArt. There are so many flaws in the opticals she had done. There was a ton of dirt, a ton of scratches. I marked forty places where our negative had flaws that the 1967 print from Sweden didn’t have. I wanted to have them corrected. Vincent [Pirozzi] at Modern Videofilm and Joe [Lindner] at the Academy said, ‘You can spend $10,000 to correct those forty differences, but nobody will see them because to make this film look perfect would cost $100,000.’ And even then you’re not bringing it back to 1967, you’re improving it far beyond what Shirley Clarke ever intended or ever had in 1967. Even if you spent the $100,000, it would be wrong.

So, the choice came back to spending $10,000 to correct these other things that no one would notice. We decided we’d leave it untouched. So it’s a sort of anti-restoration, after putting the film back together.

KW: Anti-restoration is an apt way of summing up the project. Shirley Clarke is trying to make it look distressed, trying to make it look degraded, trying to make it look like outtakes. She lets the camera go out of focus more than any professional crew ever would have permitted. She’s exaggerating the degradation and the rawness in her aesthetic.

DD: Clarke gave two important interviews about this; one was an audio interview with James Blue in 1969 and the other was an article I read from 1965. She talks about her disappointment with The Connection. She had these huge fights with Arthur Ornitz, the cinematographer. He was a 35mm professional cinematographer. He wanted it to look perfect and she wanted The Connection to look rough and beat-up, like a film left behind by a director who gave up on the film. That’s the story The Connection is about.

She was greatly disappointed that The Connection was so clean and so shining. When we were doing Portrait of Jason, boy, did I remember those words! I wanted to make sure that we paid respect to Shirley Clarke’s aesthetic in that film.

She was greatly disappointed that The Connection was so clean and so shining. When we were doing Portrait of Jason, boy, did I remember those words! I wanted to make sure that we paid respect to Shirley Clarke’s aesthetic in that film.

KW: I think that’s a great way of summing up. Are there any other projects that Milestone is working on right now?

DD: We are working on Film by Samuel Beckett, which Ross Lipman at UCLA has restored. Actually, Ross is directing the documentary about the making of the film, which is an amazing story. We are working on In the Land of the Head Hunters, the Edward S. Curtis film of 1914 featuring the Kwakwaka’wakw Indians of the Pacific Northwest, who used to be known as the Kwakiutl. That has been restored by UCLA and we’re bringing that out in the next few months.

We’re also doing another Charles Burnett-Billy Woodberry film, Bless Their Little Hearts. That is one of our favorites.

KW: That’s wonderful. We were talking about it a few years ago. We were both enthusiastic, but you said the music rights would be difficult.

DD: They probably are going to be. [Laughs] I haven’t faced that part yet. There is less music than Killer of Sheep. Most of it is by Archie Shepp, so I hope we can get those cleared relatively easy.

• • •

The Chicago Restoration Premiere of Portrait of Jason will be held at the Music Box Theatre on May 29 at 7:00pm. The event is co-sponsored by the Northwest Chicago Film Society, Black Cinema House, and the Reeling Film Festival. Special thanks to Dennis Doros, Dave Jennings, Mike Quintero, Michael W. Phillips, Jr., Brenda Webb, and Beckie Stocchetti.