Aside from Pulitzer-winning source material or a dose of Merchant-Ivory patina, subtitles are often judged the surest indication of a movie’s pedigree. Dialogue that would provoke guffaws and catcalls in its native tongue, the truism goes, reads profound and poetic in subtitled subterfuge.

Aside from Pulitzer-winning source material or a dose of Merchant-Ivory patina, subtitles are often judged the surest indication of a movie’s pedigree. Dialogue that would provoke guffaws and catcalls in its native tongue, the truism goes, reads profound and poetic in subtitled subterfuge.

The snobbism cuts both ways, of course. “It’s already possible to determine whether someone is middlebrow or upperbrow,” Hollis Alpert advised his Saturday Review readers in 1959, “depending on whether the word Bergman suggests Ingmar or Ingrid.” Snarkier still was Mike Rubin’s contention in the Village Voice in 2001 that “the Osama bin Laden videotape was, for most American viewers, probably their first experience watching something with subtitles.” (Grant Rubin the courage of his hilarious convictions, at least; he went on to compare the aesthetic strategies of the terror tape to recent work of Jacques Rivette and Mohsen Makhmalbaf.)

Subtitles are, of course, also thought to seriously limit a film’s box office potential, restricting play to art houses and specialty theaters. Intouchables, the feel-good French drama that’s earned over $400 million worldwide, has grossed a little over $10 million in the US—which is considered outstanding for subtitled fare these days. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon made $128 million stateside thirteen years ago, which was enough for Entertainment Weekly to declare Ang Lee’s neo-wuxia epic the odds-on-favor template for twenty-first-century cinema. By the time, Zhang Yimou’s Hero, the natural successor to Crouching Tiger, appeared on American screens to test this thesis, it was already old news to specialists. (Hero had been circulating on import DVDs for two years.) What’s more, Hero had already been supplanted by the subtitled event of the new millennium (and several millennia before that): Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, which proved that even archaic Aramaic was no barrier to wide circulation.

Subtitles have been part of the movie-going landscape for so long that we process that them largely in cultural terms. The technical considerations are secondary.

Subtitles have been part of the movie-going landscape for so long that we process that them largely in cultural terms. The technical considerations are secondary.

But subtitles were hardly inevitable or instantly indicative of a cultural divide. They were but one solution to the upheavals of the talkies.

During the silent era, films traveled across borders with considerable freedom. Outfitted with a new set of titles for local markets, films could be shown anywhere. (A confusing semantic point for scholars and general readers alike: contemporary accounts often describe the dialogue cards and narrative interpolations of the silent era as subtitles. As near as I can tell, we retroactively began calling them intertitles after the arrival of the sound era to distinguish from the bottom-of-the-screen, simultaneous translation variety.) Thus the Italian and French film industries briefly eclipsed American efforts—at least until the Great War destroyed every production center aside from Hollywood. American stars dominated screens around the world. Even the Soviet Union loved Yankee personalities, as evidenced by A Kiss from Mary Pickford, a romantic comedy built around a stealth recording of a visit from America’s Sweetheart.

The sound transition facilitated corporate consolidation but simultaneously threatened market share. The major studios survived intact and raised the barrier for entry for independents. Theater-owners required complex financing deals to keep the doors open—a ready parallel to the digital conversion of today. But what about international markets? Audiences wanted to hear actors speak the local argot, which opened up the terrifying possibility of indigenous product actually competing with neo-colonial wares. Poorly-capitalized domestic companies could upend the plans of major studios.

Sound recording and mixing were still in their infancy, so dubbing over an entire soundtrack was impractical and difficult. Subtitles required another stage in the printing process, and anyone who’s seen White Zombie or Wild Girl (both 1932) with their almost indecipherable optical effects can attest to the truly meretricious quality of duping stocks in the early talkie era. The subtitling option was adopted by small-time operators but largely ignored by the majors. In the foreword to his collection Saint Cinema, Herman G. Weinberg recounts being cajoled into developing the primitive process by his employers at the Fifth Avenue Playhouse:

[S]omeone said that was a contraption called a moviola, which had been used for editing films all along. It had a footage counter and now a photo-electric cell that made it possible to measure the length of every piece of dialogue in the film. All that was necessary was to figure out how many words could be read in the time it took them to say it. And I was elected to do it.

I began very gingerly, not more than maybe twenty or thirty translations in the form of titles (at the bottom of the screen, that was the logical place) per ten-minute reel; then I watched the audience in the theater to see if they would have to bob their heads up and down to look at the picture, then read the title, etc.—just as in a tennis match the spectators turn their heads from left to right to follow the players. Nope—they didn’t bob their heads, they just cast down their eyes and lifted them up again. Good! I was emboldened to add more titles and more until, if the dialogue of a film warranted it (like the marvelous Marius–Fanny–César trilogy of Marcel Pagnol, for instance), I might have as many as a hundred to a hundred and fifty dialogue titles to each ten-minute reel.

(The gingerly attitude in subtitling survived long after Weinberg grew out of it. Film collectors and seasoned repertory regulars have learned to expect very sparse translation in prints struck in the ‘50s and ‘60s and beyond.)

And so the third option—the one that seems the most elaborate and wasteful to us now—was briefly adopted: concurrently filming multiple versions of major productions.

Were the alternatives ever attempted on the same scale? Perhaps, but then, a pedestrian dub job could hardly command the same beguiling interest for us today. A folly that lasted a bare two years in Hollywood, the counterintuitive existence of these shadow films must be answered.

Were the alternatives ever attempted on the same scale? Perhaps, but then, a pedestrian dub job could hardly command the same beguiling interest for us today. A folly that lasted a bare two years in Hollywood, the counterintuitive existence of these shadow films must be answered.

Studio production schedules had already been strangled into something resembling a very efficient science by the dawn of the talkies, and most everyone was under contract anyway—contracts that stipulated nothing one way or another about working seven days a week or long past midnight. And so there was a German Anna Christie and a Spanish variant on Laurel and Hardy. Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail was filmed in no less than five simultaneous versions: a widescreen version in Fox’s 70mm Grandeur process and four standard 35mm versions in English, Spanish, French, and German. (The latter was purportedly revived to some success in Germany following World War II.)

And, importantly, Hollywood was not the only production center attempting to corner the international market through alternate versions. Germany also made significant strides in this area, with three versions (German, French, English) of The Congress Dances. The Criterion editions of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse and The Threepenny Opera present both the German and the French versions for home consumption.

Scholarly interest in Multiple Language Versions has been a long time coming and it’s not at all clear how many of these curios are still with us. Paul Fejos long enjoyed a higher reputation in France than in the US, on the basis of Lonesome, but also the French-language version of The Big House that Fejos shot for MGM. Francophile Andrew Sarris even cited Révolte dans la prison when putting Fejos forward as a ‘Subject for Further Research’ in The American Cinema, but had he seen it? Does it still exist?

Every film archive faces formidable cataloging challenges, and verifying whether their holdings contain variant editions of established classics demands drudgery with little chance of reward. Unique material is the prize that drives preservation priorities. Every respectable archive has a print of Fritz Lang’s M, so it’s neither surprising nor damning that the BFI did not realize that it held a copy of the forgotten English-language version until 2005. This version is now available as an extra on the Criterion and Masters of Cinema Blu-ray editions of M, with the latter including a realistic and edifying account of the discovery of the English version and the archival issues involved.

Universal’s Spanish-tongued Drácula is doubtless the most celebrated and widely-seen of the Multiple Language Versions today. Its fame stems, in part, from its unlikely re-discovery (a full version was finally assembled when the last missing reel was found in a Cuban archive in the 1980s), but also from the perceived creakiness of the Lugosi classic that it remakes. The Tod Browning-Bela Lugosi Dracula is a great film, but one that requires a specific kind of engagement; seen in anything but a pristine print, the subtlety of its staging and cutting is completely lost. Viewed on TV, it’s merely stodgy. Fans instinctively respond to the lively camera movement of the Spanish version, as well as its earthier attitude. The tops on the actresses are shorter and Dracula’s Transylvanian castle has real vermin. (In the English version, we get armadillos instead.)

Universal’s Spanish-tongued Drácula is doubtless the most celebrated and widely-seen of the Multiple Language Versions today. Its fame stems, in part, from its unlikely re-discovery (a full version was finally assembled when the last missing reel was found in a Cuban archive in the 1980s), but also from the perceived creakiness of the Lugosi classic that it remakes. The Tod Browning-Bela Lugosi Dracula is a great film, but one that requires a specific kind of engagement; seen in anything but a pristine print, the subtlety of its staging and cutting is completely lost. Viewed on TV, it’s merely stodgy. Fans instinctively respond to the lively camera movement of the Spanish version, as well as its earthier attitude. The tops on the actresses are shorter and Dracula’s Transylvanian castle has real vermin. (In the English version, we get armadillos instead.)

For all these reasons, Drácula has earned a substantial following in the horror community. Its ready availability on video hasn’t hurt, either. It’s been co-billed by Universal Home Entertainment with the Lugosi Dracula on three DVD iterations since 1999 and was upgraded to hi-def in the recent Blu-ray box set. And although Universal has a 35mm vault print of Drácula, it doesn’t get shown much because, unlike the DVD, it’s not subtitled.

Subtitling works through an economy of scale. Adding subtitles to a single print is expensive, often prohibitively so—especially when the print is manufactured as a matter of routine asset protection rather than mounted for theatrical release. Although tech-savvy cinephiles have proudly synced home-made subtitle files to DVD rips floating around in the torrent backwaters, doing the work for a film print is considerably more complicated. Video can be measured in timecodes, but films are still counted in frames for purposes of printing and subtitling. A list of translated dialogue and timecodes isn’t sufficient to produce a new subtitled print. A laboratory technician needs to produce a spotting list, which assigns each subtitle a frame-accurate footage position. (What happens if the list isn’t accurate? I recall with some fondness an infamous 16mm print of Aguirre, the Wrath of God where every subtitle in the first reel preceded the dialogue by a few seconds. That print was still circulating as late as 2006.)

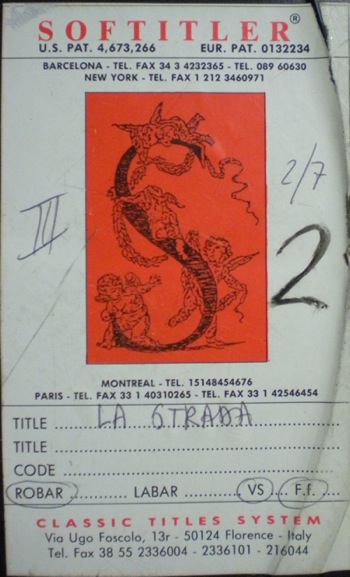

The art of coordinating perfect and readable subtitles is often handled by specialty outfits unaffiliated with the lab that produced the print. (Titra and LVT are two such companies.) Producing a spotting list represents an upfront investment on top of the expense of subtitling each print. For small jobs, laser subtitles produced from the spotting list are the most efficient vehicle for translating dialogue, but a wide release can justify the cost of striking a subtitlted negative. Of course, once something is added to the negative, it cannot be removed from the negative or from the prints struck from that negative. Assuming that the producer still wants non-subtitled prints for the domestic market, this means paying for a second negative that will be used expressly for making subtitled prints. If the distributor anticipates making only a handful of subtitled prints, the expense of a second negative is difficult to justify.

The art of coordinating perfect and readable subtitles is often handled by specialty outfits unaffiliated with the lab that produced the print. (Titra and LVT are two such companies.) Producing a spotting list represents an upfront investment on top of the expense of subtitling each print. For small jobs, laser subtitles produced from the spotting list are the most efficient vehicle for translating dialogue, but a wide release can justify the cost of striking a subtitlted negative. Of course, once something is added to the negative, it cannot be removed from the negative or from the prints struck from that negative. Assuming that the producer still wants non-subtitled prints for the domestic market, this means paying for a second negative that will be used expressly for making subtitled prints. If the distributor anticipates making only a handful of subtitled prints, the expense of a second negative is difficult to justify.

Some films won’t see returns enough to justify a subtitled negative or even a single subtitled print. In that case, it falls to the exhibitor for a creative workaround. Sixteen-millimeter college film societies produced mimeographed synopses, an opera-derived practice still used on occasion by Anthology Film Archives. (So storied are the Anthology synopses that I’d read about them three or four times as a teenager, long before ever attending a show there.) Some exhibitors, entranced by the possibility afforded by the theater loud speaker, read a translation aloud from the theater floor.

In recent years, soft subtitling has gained popularity. Impractical on a mass release, even on the art house circuit, it’s the exclusive province of cinematheques. This means that the exhibitor prepares or obtains a subtitle list and transfers the content to a PowerPoint presentation, which is run concurrently with the print from a digital projector elsewhere in the auditorium. Though theoretically such a practice could be automated and left to run on its own, film is inherently a riskier (and sexier) medium than that. What would happen to the synchronization if the projectionist misses a change-over? A human operator, preferably a native speaker, is essential for advancing the slides and judging the temperature of the room. The necessity of a full rehearsal is another aspect that brings the soft-subtitled film closer to a high-wire kind of live theater.

If an exhibitor goes to the trouble of running an unsubtitled print and preparing soft subtitles, it’s a big deal and speaks to major faith in the power and importance of the film on the exhibitor’s part. It’s a lot of trouble, but it’s better than letting the film sit in the vault forever because it’s not subtitled. We did it a little over a year ago with Liliom and we’re doing it again this week with Drácula. We can’t say when you’ll next have a chance to see this in a theater, in 35mm, but this print is certainly going back into the crypt at sunrise.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Drácula in a 35mm print from Universal at the Portage on Wednesday, February 13. Special thanks to Paul Ginsburg and Dennis Chong. For more information about the screening, please see our current calendar. Have you heard that we’re doing the subtitles ourselves?