Can anything else be said about The Night of the Hunter? After a BFI monograph, two book-length accounts of its production, an exhaustive Criterion Collection edition, and numerous critical appreciations, one fears not. Robert Mitchum’s monologues are quoted with giddy abandon and the spectral image of Shelley Winters underwater is recalled with undiluted emotional immediacy. James Agee’s screenplay (long ridiculed by associates who outlived him) is now released under the banner of the Library of America—an honor that the screenplay basically aspired to long before such a collection existed.

By now, this strange picture, roundly rejected upon its initial release, has been overtaken by its own special class of critical clichés. It blends the pastoralism of Griffith with the angular terror of the Weimar Cinema. It’s a horror show with a strong Sunday School message. It’s a great challenge to (or affirmation of?) the auteur theory—the sole film directed by Charles Laughton, at once sui generis and a heartbreaking suggestion of what wonders he may have produced afterward were it not for the film’s box office troubles. (And we’re not exempt from this either: in calling The Night of the Hunter a Christmas classic, we’re hoping to promulgate a new cliché, no ill will towards It’s a Wonderful Life or White Christmas intended.)

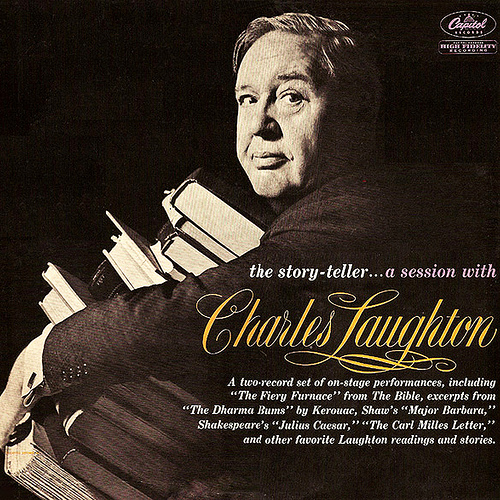

The freshest way to look at The Night of Hunter is actually to listen to it. It’s much more provocative and productive to take The Night of a Hunter not as an directorial outlier but rather as a climax to Laughton’s work across several media. In the early fifties, Laughton’s film roles were few, but he remained an inescapable public presence. The theatrical partnership between Laughton and producer Paul Gregory encompassed a busy lecture tour and three extraordinarily well-received stage productions: Shaw’s Don Juan in Hell, Benet’s John Brown’s Body, and Wouk’s The Caine-Mutiny Court Martial. All these events revolved around the special quality of words read aloud, with Laughton literally hauling a stack of books up to his lectern when presenting An Evening with Charles Laughton. The more elaborate productions of Shaw and Benet were not really so much more elaborate—Laughton’s actors would take the stage, rivet themselves to the stools, and perform the texts in a manner that would now be called reader’s theater.

The freshest way to look at The Night of Hunter is actually to listen to it. It’s much more provocative and productive to take The Night of a Hunter not as an directorial outlier but rather as a climax to Laughton’s work across several media. In the early fifties, Laughton’s film roles were few, but he remained an inescapable public presence. The theatrical partnership between Laughton and producer Paul Gregory encompassed a busy lecture tour and three extraordinarily well-received stage productions: Shaw’s Don Juan in Hell, Benet’s John Brown’s Body, and Wouk’s The Caine-Mutiny Court Martial. All these events revolved around the special quality of words read aloud, with Laughton literally hauling a stack of books up to his lectern when presenting An Evening with Charles Laughton. The more elaborate productions of Shaw and Benet were not really so much more elaborate—Laughton’s actors would take the stage, rivet themselves to the stools, and perform the texts in a manner that would now be called reader’s theater.

Laughton’s reading talent was already well-known. The popularity of his recitation of the Gettysburg Address in Ruggles of Red Gap led naturally to a commercial 78 rpm recording of the same. (Those curious about this release can scrounge the junk bins of your local record store or import the British Blu-ray of Ruggles from the Masters of Cinema label, which includes the audio as an extra.)

Regular visits to a Southern California military hospital in 1943 sealed the deal. Per Laughton:

I read innocuous and sentimental things which I thought would please them. I read three times a week, but one day I tried something heavy and tragic, and there was an immediate response. They started to talk about their own problems—being in bombers over Germany, or in foxholes, or how they felt after they had been maimed. And so I found that serious literature was a great help to them because other people in centuries gone and in the present had all the experience that are to be had, and the GI’s felt they were not alone. This resulted in me having to read in a larger room at Birmingham because the first, small room could not contain all those who wanted to come. And then I had to read in a larger hall still. And when I was reading from all the books I loved, I found the business of reading aloud was a matter of making the effort to communicate something you love to people you love.

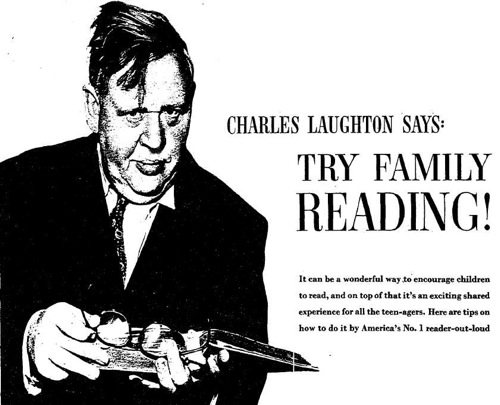

Laughton’s argument for this intimate brand of performance continued in the pages of This Week, the mighty Sunday newspaper supplement, which offered three pages to ‘America’s No. 1 reader-out-loud’ in a promotional tie-up with The Night of the Hunter:

Moses wrote the Ten Commandments on tablets of stone from divine inspiration. The tablets of stone have long been dust, but the words live. Man’s greatest and noblest works of genius built from brick and mortar crumble and perish, but words do not die…

I was once invited to read the Bible to an audience of ministers at Occidental College. Afterward, one of the ministers told me, “You know, we ministers make a fetish of the Bible. Your turn it into a dramatic, earthy tale of real people.”

I assure you that you can do the same thing if you will try reading the Bible out loud in your own living room, just as our ancestors used to do in their daily Bible readings.

(Is it any wonder that Laughton originally planned to open The Night of a Hunter with a scene of himself reading aloud from the Bible? Or that the film’s soundtrack LP was actually a 35-minute condensation of the story as read by Laughton?)

(Is it any wonder that Laughton originally planned to open The Night of a Hunter with a scene of himself reading aloud from the Bible? Or that the film’s soundtrack LP was actually a 35-minute condensation of the story as read by Laughton?)

Laughton’s approach was essentially a more democratic and easy-going rendition of the University of Chicago’s contemporaneous Great Books initiative. While Robert Maynard Hutchins attempted to encyclopedia-ize the landmarks of Western Lit, Laughton promoted the experience of listening as a special kind of engagement. It was primarily emotional, rather than textual, uplift.

Despite its photographic virtuosity, it’s this spoken aspect of The Night of the Hunter that completely sets it apart from its contemporaries. (Its only real companion is The Saga of Anatahan.) Almost every line spoken in the film is delivered with one sort of dialect or another, but it’s never just a gimmick. Laughton and Agee are deeply interested in the patterns of vernacular speech, with each syllable functioning as melody, not rhetoric. It’s pure sound—an unfolding oral ritual that aspires to folk permanence.

Certainly the speech is affected: it’s a boy’s adventure yarn where everyone talks with faux Shakespearian grandiloquence. The deviations and eccentricities are expressive in themselves. The lines carry the odd phrasings and wild cadences of a kid trying to prettify a half-remembered poem until it sounds like a lost verse of the King James Bible. The Night of the Hunter would never be confused with naturalism, and that’s the point: in its adolescent yearning and gawky malapropism, in its living memory of an America that never quite existed, it embarks on a project that’s more delicate and insightful than mere naturalism.

It’s also, notably, a world apart from the approach embodied by contemporary films like Some Came Running and Wild River. Great though these are, you can never quite shake the feeling that the screenwriter has resorted to hillbilly verbiage as a shortcut to characterization. The remarkable performances of Shirley MacLaine and Lee Remick struggle mightily against this sociological strait jacket, with even the most emotionally immediate moments damaged by the insistent reminder that these women are irredeemably uneducated.

There’s no such condescension in The Night of the Hunter, largely because the film refuses to exploit class difference for the sake of melodrama. When Evelyn Varden says that she’s more interested in canning than sex, we chuckle, but we also recognize a real preference delivered without a note of doubt or self-consciousness. This is an important distinction that feeds directly into another of the film’s major achievements—its sober hysteria.

As noted, the original reviews of The Night of the Hunter were generally not sympathetic to this contradiction. One would expect some degree of understanding from a specialist publication like Films in Review—what better audience for a feature-length Griffith homage?—but they complained of arty pretension and over-extended ambition like many other outlets. The Chicago Daily Tribune rejected its violence as simultaneously ugly and laughable. The harshest notice probably came from the Washington Post, which accused Laughton of “cheap taste and apparent contempt for simple people,” resulting in “a hideous travesty on the human race.” (Three weeks after that pan, the Post’s movie critic devoted a column to a new trend of cynicism in cinema, bracketing The Night of the Hunter with The Big Knife and Rebel Without a Cause. All these films willfully contradicted the author’s assertion that “the rightness and generosity of individuals are as strong as they have ever been.”)

As noted, the original reviews of The Night of the Hunter were generally not sympathetic to this contradiction. One would expect some degree of understanding from a specialist publication like Films in Review—what better audience for a feature-length Griffith homage?—but they complained of arty pretension and over-extended ambition like many other outlets. The Chicago Daily Tribune rejected its violence as simultaneously ugly and laughable. The harshest notice probably came from the Washington Post, which accused Laughton of “cheap taste and apparent contempt for simple people,” resulting in “a hideous travesty on the human race.” (Three weeks after that pan, the Post’s movie critic devoted a column to a new trend of cynicism in cinema, bracketing The Night of the Hunter with The Big Knife and Rebel Without a Cause. All these films willfully contradicted the author’s assertion that “the rightness and generosity of individuals are as strong as they have ever been.”)

These reactions are especially interesting because our own feelings about The Night of the Hunter are largely their opposite. After decades of quotable killers in thrillers like The Godfather, Scarface, The Silence of the Lambs, and No Country for Old Men, Mitchum’s charismatic destroyer seems essentially modern and, in that sense, unremarkable. What makes The Night of the Hunter unique today is the manifest sincerity of its small-town values. Though Laughton and Agee acknowledge that horrible evil can visit West Virginia’s Cresap’s Landing, this is no exposé of the repressed void at the town’s heart. Whereas films like Blue Velvet and A History of Violence construct a parody of America to be disassembled, strawman-like, by kinky second-act revelations, The Night of the Hunter keeps the faith. (Literally. For a movie about religious hypocrisy, The Night of the Hunter can still recall chapter and verse.) Lillian Gish is the embodiment of goodness and wisdom, offered with no irony whatever. This is a film that tastes adult pain, but chooses a child’s moral compass anyway.

Is this a copout? Perhaps, but remember that Laughton viewed tragedy as a form of empathy and as an instigator to empowerment. Recognizing the great darkness of the world affirmed the resilience of the children who abide and endure. Like a live reading or a revival meeting, The Night of the Hunter achieves a trance-like conspiracy between speaker and listener.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society screens The Night of the Hunter in a terrifying 35mm print on Wednesday, December 19 at the Portage Theater. (Note the proximity to The Holiday Season.) Special thanks to Chris Chouinard of Park Circus. Please see our current calendar for more information.