Since avant-garde movies first attracted a substantial audience in America under the auspices of indecency and subversion of established ideas about politics, art, society, and especially sexuality, many don’t expect that such films can also be exceedingly gentle, even reverential towards their subjects.

Since avant-garde movies first attracted a substantial audience in America under the auspices of indecency and subversion of established ideas about politics, art, society, and especially sexuality, many don’t expect that such films can also be exceedingly gentle, even reverential towards their subjects.

But if an artist can engage with material by cutting it up, mocking it, and exposing its strains of hypocrisy and social disease (as, say, Bruce Conner does in A Movie), can’t avant-garde filmmakers also suggest an altogether different kind of awareness and insight by leaving something alone? To edit is to violate. That’s the notion that links the three films we’ll be showing at Cinema Borealis on Sunday night as a prelude to this year’s edition of Home Movie Day. They’re all fashioned from found footage, specifically home movies discovered or sought out by the filmmakers.

Divorced from the personalities and memories they originally sought to commemorate, orphaned home movies nevertheless remain deeply, perhaps uncomfortably, personal. Anonymous 16mm reels are often physically fragile, but they’re also emotionally delicate, as if we’ve stolen a page from someone else’s diary. We shouldn’t be seeing this. (It’s a testament to the loose norms of home movies that we need only a few frames to establish who’s who in family and community hierarchies. There’s a collective order to be found in miles of unrelated footage.)

Ron Finne, who collected the material seen in People Near Here by placing classified ads in Bay Area newspapers, allows the footage to follow its own logic. Individual clips are unedited, though the final product is definitely shapely and cumulatively moving. The catalog description for the film provided by the Film-makers Coop makes a case not just for People Near Here, but the cultural validity of home movies generally: “In this film, Americans — across stages of life, across decades, in backyards, at a graduation picnic, on a beach and in other ordinary places — reveal silly, happy, intense and sad things about themselves, mostly with exuberance and dignity.”

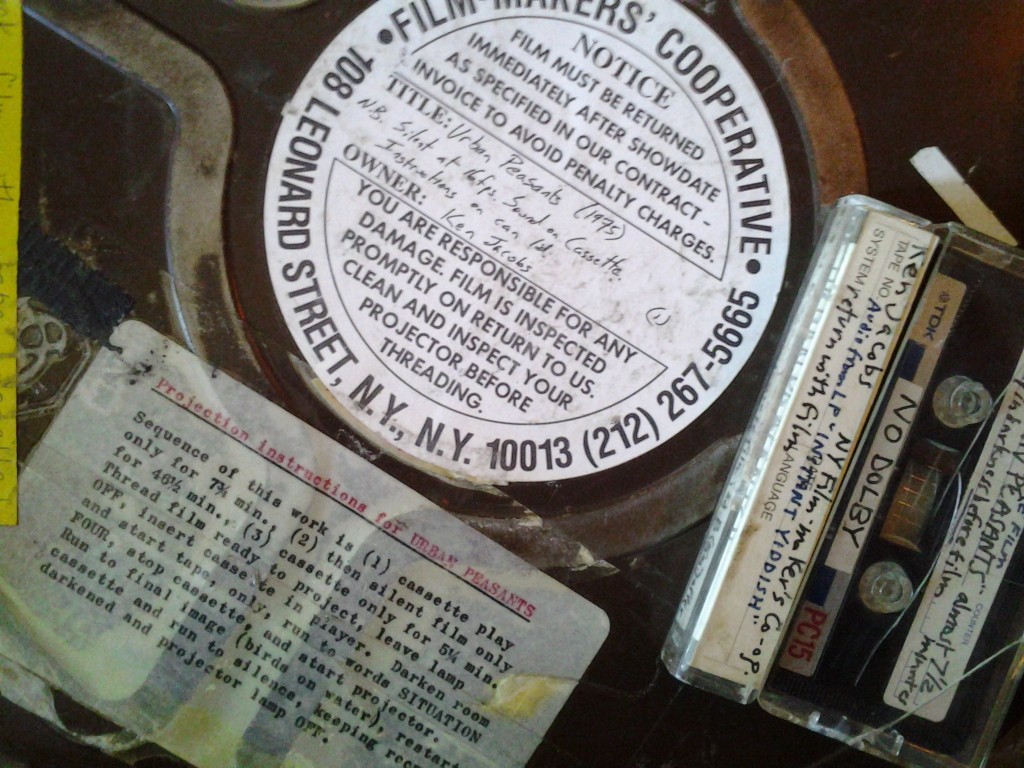

Ken Jacobs’s Urban Peasant, drawn from decades-incubated 16mm footage from the artist’s wife’s aunt, contains all these things and, in its best moments, adds a note of impossible cardboard wonder—a child’s fantasy in reality’s clothing. Its inhabitants wander through gardens and slums as if in an endless dream. (If ever there was a film that earned Paul Éluard’s famous epigram, “There is another world, but it is in this one,” it’s Urban Peasants.) Most fantastic and heartbreaking of all is Jacobs’s sole intervention—bookending the home movie footage with selections from an Instant Yiddish LP, as if the Diaspora possessed the autonomy to decree an official language in Brooklyn and Eastern Europe.)

We’re also showing a divisive new film called Shit Rat from Dave Rodriguez, Chief Projectionist at George Eastman House. It’s an unedited 1200’ reel with a mysterious backstory. I talked with Dave about Shit Rat over email:

How did you come upon the film that became Shit Rat?

When I was in graduate school at the University of Florida I discovered that we had a seldom-used archive of 16mm films—mostly educational and industrial shorts and a good amount of reduction prints of feature films. The place was sort of a wreck so I spent a summer down there reorganizing and recataloging as much of it as I could. In doing so I accumulated a large pile of “unidentifieds” that I would spend my Fridays watching and trying to, naturally, identify. I came across Shit Rat on such a Friday, and it was the only thing that I watched twice in a row. I asked around regarding its origins and creator, and nobody could tell me anything. When I left UF to start work as a film archivist, I took it as a little souvenir.

What qualities did the footage have that stimulated you?

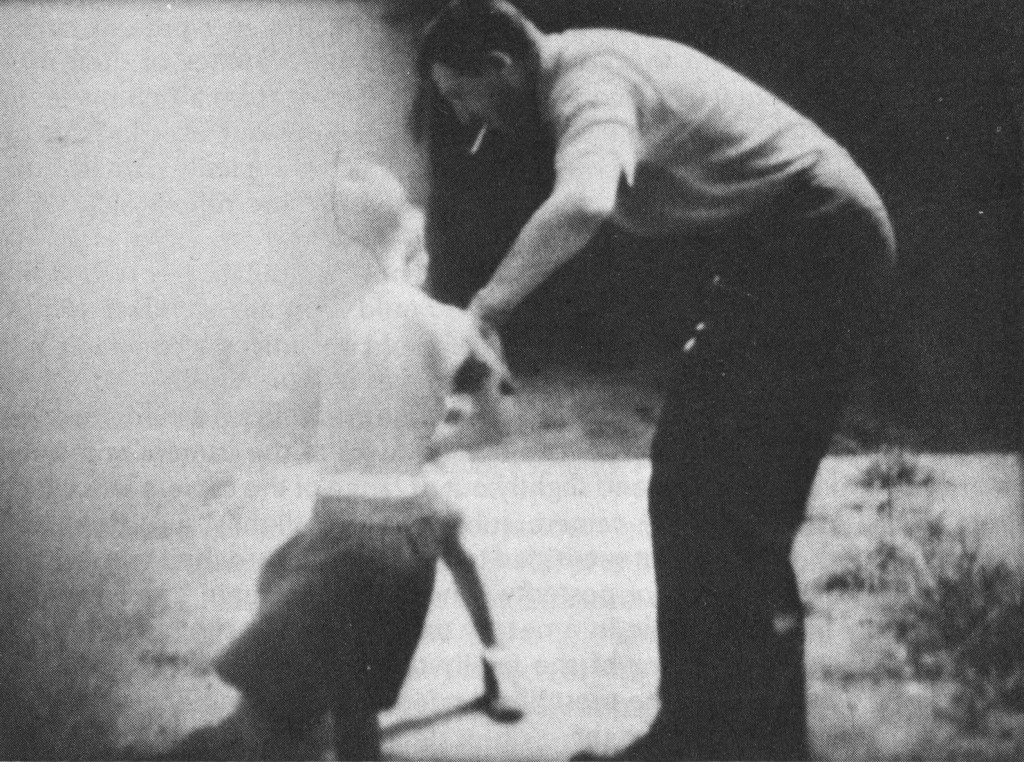

It stands out as something that seems unfinished, or perhaps in the process of becoming something else, especially in the context of everything else I was working with that summer. The “negative” qualities of the image, the lack of a soundtrack, and the weird juxtapositions hooked me from the start. That whole sequence in the woods was what really stuck to me at first viewing. You get to glimpse this harsh, inverted version of the world–white windows, black sky, broken tv’s–what’s not to fall in love with? That and the fact these images just kind of fell into my lap while I was eating a sandwich in a dark basement made it a truly exciting discovery.

Did the work of other filmmakers who utilize found footage attune you to what’s special about the Shit Rat footage?

When I found Shit Rat I immediately thought of Ken Jacob’s Perfect Film and the Film Ist series by Gustav Deutsch. I’m not sure how much in common (stylistically, ideologically) Shit Rat has with these other works, but as a hoarder of VHS tapes and any old scraps of film I can find I appreciate any attempt at re-purposing moving images outside of their original production/intent. My own work has kind of followed this track and it’s something I hope I can continue to do for a long time working in film preservation.

I remember that, when first seeing the film, I couldn’t decide whether it was a negative or positive, whether I had threaded it in the projector backwards. At times it looks hand-processed. What do you think it is exactly?

My guess is that some filmmaker, probably a student or professor at UF, shot this on b/w reversal stock, hand processed it at UF (I know this is technically possible there) and either forgot about it or just left it down there. There weren’t any identifying markers on the print and the thing didn’t even have leader until you and I watched it together. Whatever it is, it’s my problem now.

I’ve long had a theory that people who work as projectionists, by virtue of their very tactile relation to film itself, tend to view and experience films on screen differently than most do. In many cases, I think, it makes them more sympathetic to avant-garde films. Is this crazy or does it make sense?

It definitely makes sense. When I’m inspecting and then projecting a film you get to experience its double life as an object and an image; you see it’s scars, splices, filth, what-have-you in all four dimensions. And I feel personally drawn to works that play with these issues of physicality, works that traditionally fall into the canon of avant-garde/experimental/critical/underground/etc. cinema. It’s not crazy, but I don’t think it’s something your casual movie-goer thinks about or even considers. With viewing experiences going more digital, people are thinking less about where moving images actually come from or how they’re created. There’s a weird sense of entitlement attached to it…but I pontificate. And who I am I to tell you how to enjoy a movie?

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening People Near Here, Urban Peasants, and Shit Rat in 16mm prints at Cinema Borealis on Sunday, September 16. The show is co-presented by Chicago Film Archives in conjunction with the tenth anniversary edition of Home Movie Day. (Mark your calendars: October 20.) For more information, please see our calendar here.