Our sixth (and best?) season starts on Wednesday at the Portage with Hands Across the Table. The occasion affords us an opportunity to talk about a programming issue that’s usually not critically aired in public—the impact, presumed or otherwise, that a film’s presence on home video has on its viability in a repertory slot.

Our sixth (and best?) season starts on Wednesday at the Portage with Hands Across the Table. The occasion affords us an opportunity to talk about a programming issue that’s usually not critically aired in public—the impact, presumed or otherwise, that a film’s presence on home video has on its viability in a repertory slot.

Programming a calendar is always a multi-dimensional balancing act, and the availability of the films in other formats is a central factor in that equation. Present a calendar where every title is available on DVD and Blu-ray and your audience is likely to shrug it off—the titles are familiar, perhaps over-familiar, and there’s no sense of urgency in seeing them again. If you miss the screening, you can just pull out the disc from the shelf in the family room. A Casablanca or a Psycho feels omnipresent anyway, and a programmer can’t reasonably expect folks to approach such screenings as anything other than business as usual. (After all, you’ve owned a VHS, a DVD, a special anniversary-edition DVD reissue, a Blu-ray, and if there’s another edition with specially-branded shot glasses or an umbrella, you can’t deny you wouldn’t be tempted…)

Of course, one of the foundational, but often implicit, ideas behind repertory cinema is that its offerings are unique. You can flop into any multiplex and be reasonably sure there’s another showing of The Dark Knight Rises or The Expendables 2 starting sometime in the next 45 minutes. You don’t even have to check the showtimes beforehand. Rep, by contrast, forces people to plan in advance, jot down titles in Moleskines, sometimes change their social plans to accommodate a one-night-only screening.

And nothing says ‘one-night-only’ like a film that’s absolutely not available in any other format. (For those keeping score at home, such items on this season’s calendar include El, Thanks a Million, Upstream, Sand, The Saga of Anatahan, Chad Hanna, Just Imagine, and all the films in the pair of Borealis programs devoted to Home Movies and the Avant-Garde.)

And nothing says ‘one-night-only’ like a film that’s absolutely not available in any other format. (For those keeping score at home, such items on this season’s calendar include El, Thanks a Million, Upstream, Sand, The Saga of Anatahan, Chad Hanna, Just Imagine, and all the films in the pair of Borealis programs devoted to Home Movies and the Avant-Garde.)

Emphasizing the lack of other options has other useful dividends. If a film isn’t easy to see, then it presumably follows that someone had to perform a good deal of non-easy legwork (e.g., tracking down a print, negotiating with a film archive, navigating a thicket of contradictory copyright claims, procuring promotional stills for films that received minimal promotion in the first place, etc.) to shepherd it back to the screen. Ideally, a super-rare screening works as a teaching moment: it forcibly reveals to the audience all the frequently unseen labors that go into a single screening. And it pays to have a sensitive and well-informed audience: an audience attuned to the challenges facing the programmer and the projectionist tends to be a more appreciative and adventurous crowd.

So why not trumpet the non-availability of certain titles more prominently on our website and in our program booklet?

For one thing, tagging select screenings as ‘NOT ON DVD’ sets up a hierarchy that’s morally at odds with what we do. If the non-availability of Thanks a Million makes it seem a higher priority than, say, The Night of Hunter, then we’re left with the imbedded implication that the existence of DVD and Blu-ray copies of the latter makes theatrical viewing less urgent and imperative. Yet both titles have equal claim to being seen in 35mm and even the beautiful Criterion edition of the Laughton picture is a decisively different thing than seeing that film on film, where it claims the complete measure of its majesty and is most wholly itself. The availability of a substitute can’t diminish the importance of the original. (Put another way: the films we program are like an unruly assortment of offspring, and we officially and actually love them all equally. You should see every one of them.)

But there are more practical matters as well. Though some audience members flock to films on the basis of their rarity (or affectionately remind us that a certain film isn’t really that rare, as the A&O Film Society at Northwestern privately ran it in 16mm in the spring of 1987), many more don’t. A calendar consisting entirely of Not-on-DVD rarities usually alienates all but the diehards. It’s not that the films aren’t good or that the audience doesn’t trust the programmers, per se—only that a core group of recognizable titles helps to anchor, endorse, and contextualize the less-familiar ones.

Indeed, a film’s induction into the Criterion Collection usually raises its profile considerably, with the publicity and prestige associated with that brand making folks more amenable to catching it theatrically, too. (One of the unspoken secrets of programming is that you do play on people’s guilt in tandem with their better angels: ‘You’ve really never seen L’Atalante— and you call yourself a cinephile?’ or ‘You’ve watched The Ten Command- ments on TV twenty times, but do you realize that you’ve never properly seen it on the big screen?)

Indeed, a film’s induction into the Criterion Collection usually raises its profile considerably, with the publicity and prestige associated with that brand making folks more amenable to catching it theatrically, too. (One of the unspoken secrets of programming is that you do play on people’s guilt in tandem with their better angels: ‘You’ve really never seen L’Atalante— and you call yourself a cinephile?’ or ‘You’ve watched The Ten Command- ments on TV twenty times, but do you realize that you’ve never properly seen it on the big screen?)

Finally, there’s the fact that determining whether a film is available on video has become much more complicated in the last few years. With the demise of deep-catalog outfits like Virgin Megastore and Tower Records, the expectation of finding a given title at a brick-and-mortar outlet no longer seems a relevant metric. There’s no space for all but a handful of classic titles at Wal-Mart and Best Buy. (Likewise, DVDs and Blu-rays, once thought collectible and appointed with lavish booklets, are now perceived as disposal, with a die-cut recycling insignia greeting you upon cracking open the case.)

The high mastering, marketing, and storage costs associated with conventional DVD and Blu-ray releases has led nearly all the studios to embark on manufactured-on-demand discs available exclusively through a handful of online outlets. (Some initiatives, like Twilight Time, which licenses titles from Fox and Sony, sells its limited-edition wares through a single website.) Programs like the Warner Archive Collection of DVD-Rs assume two not-necessarily-compatible demographics: the savvy long-time collector with bottomless hunger for the most obscure titles and the kindly grandmother in Kansas who simply assumes that her favorite Robert Taylor movie must be available on DVD. (Among the titles on our latest calendar, The Big Night has been released on DVD-R in the plain-wrap MGM Limited Edition Collection, while The Miracle Woman is going out this week in an early Capra box set available exclusively from the online TCM Shop.)

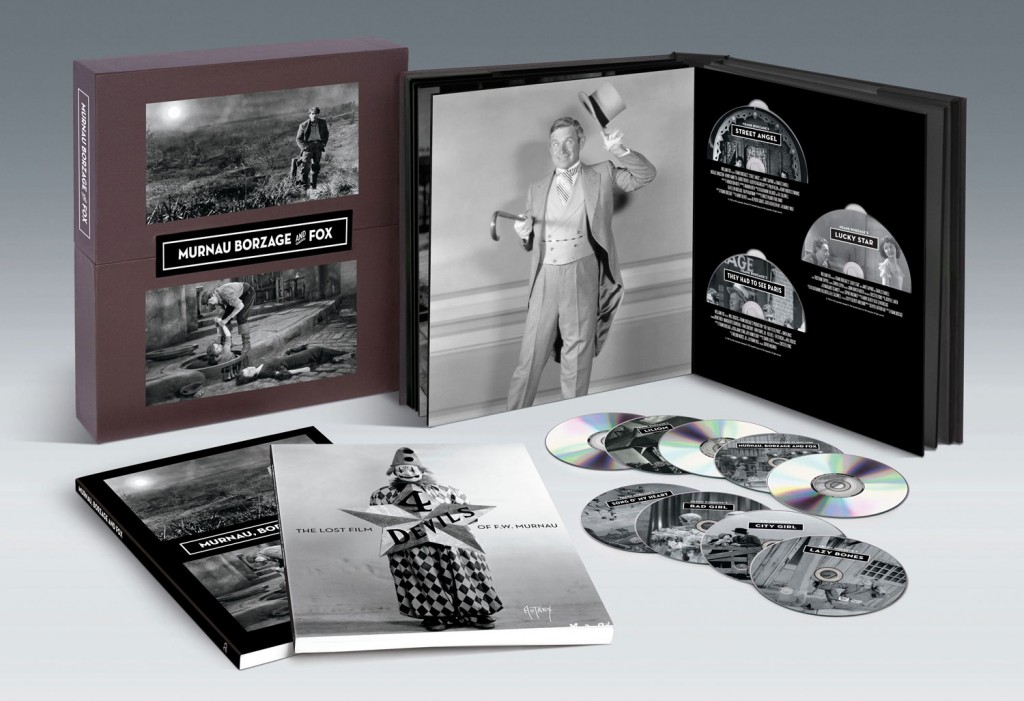

Is a movie available on DVD if you have to be an obsessive videophile to be aware of its existence? Likewise, what if a title like After Tomorrow or Wild River is only available as part of a recession-oblivious door stop? (The former is one of twelve titles that Fox Home Entertainment released in its ‘Murnau, Borzage, and Fox’ box set at $239.99 MSRP back in 2008—a worthy and improbable climax to the DVD era.) Such titles are rarely available from rental services, especially the present-day disc-weening iteration of Netflix. Speaking of Netflix, is something available on video if it’s streaming online in a pan-and-scan copy prepared for cable broadcast two decades ago?

Is a movie available on DVD if you have to be an obsessive videophile to be aware of its existence? Likewise, what if a title like After Tomorrow or Wild River is only available as part of a recession-oblivious door stop? (The former is one of twelve titles that Fox Home Entertainment released in its ‘Murnau, Borzage, and Fox’ box set at $239.99 MSRP back in 2008—a worthy and improbable climax to the DVD era.) Such titles are rarely available from rental services, especially the present-day disc-weening iteration of Netflix. Speaking of Netflix, is something available on video if it’s streaming online in a pan-and-scan copy prepared for cable broadcast two decades ago?

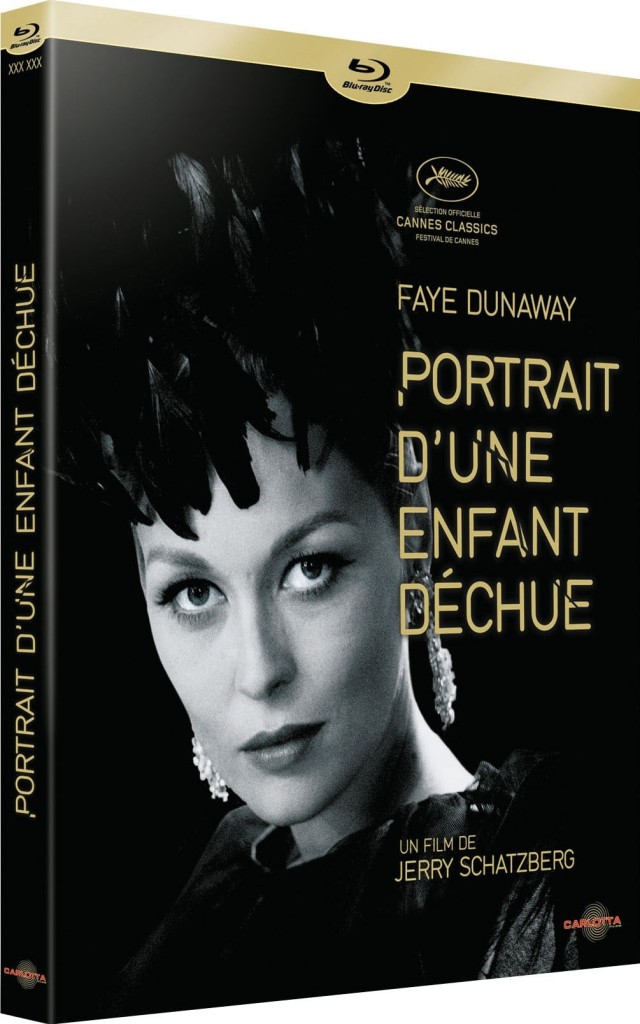

The foregoing discussion also tiptoes around the fact that the wide availability of multi-region DVD (and, to a lesser extent, Blu-ray) players further confuses the terms, as Jonathan Rosenbaum frequently details in his ‘Global Discoveries on DVD’ column in Cinemascope. Just one example: If I Had a Million is ‘Not available on video’ if your frame of reference is Region 1 DVD, but there’s a quality Region 2 copy from the UK branch of Universal, available in a ten-disc (!) W.C. Fields box set. Jerry Schatzberg’s Puzzle of a Downfall Child hasn’t merited a domestic DVD or Blu-ray release, but the French label Carlotta has issued a sepulchral Blu-ray edition under the title Portrait d’une enfant déchue last year.

As we said, you should come and see the film regardless of whether it’s available elsewhere or not.

This post is part of an occasional series about the philosophical and practical contours of film programming. For earlier entries, see here and here.