Would some films not exist at all but for their aspect ratios?

Put another way: although we tend now to think of aspect ratios as somewhat perfunctory aesthetic choices made during the preproduction process, the equation was almost exactly reversed at the dawn of the widescreen era. The shape of the screen was the engine that drove everything else and, in some cases, dictated the content before the cameras.

CinemaScope: Scope, Size, and Physical Action

Though today’s conversion to digital cinema has yielded inevitable upheavals in the structure of distribution and exhibition, the transition has proved fairly orderly and run according to plan. Compare this to 1953, when four-strip Cinerama, polarized dual-strip 3-D, and single-strip widescreen projection all sought to revolutionize the industry, to the considerable consternation and uncertainty of exhibitors, producers, union craftsmen, and everyone else involved. Fox hosted industry previews of The Robe in CinemaScope several months before its theatrical premiere, spurring all the rival studios to announce some kind of widescreen answer to Fox’s system before the bow of the Biblical epic. By mid-1954, 3-D would be phased out, Cinerama would remain confined to a few exclusive-run houses, and widescreen exhibition became predominant everywhere—all in less than eighteen months with nary a warning shot.

Conversion to CinemaScope, while cheap compared to Cinerama, still entailed a considerable outlay: new lenses and aperture plates to achieve full-width anamorphic projection, new sprocket wheels to accommodate Fox’s slightly smaller perforations, penthouse attachments to play back the four-channel magnetic soundtracks, and a curved Miracle Mirror screen to simulate the pronounced depth of Cinerama. Such a wholesale overhaul of projection equipment (which had remained more or less unchanged for two decades since the conversion to sound) required a tremendous degree of confidence on the part of exhibitors that Cinemascope product would be steady and permanent.

In February 1953, Fox announced that all new features would be shot and released in CinemaScope. So much was riding on this gamble that the studio need not just provide CinemaScope product, but assure that its subsequent releases showed the system to its best advantage. The exhibitors would need proof of the wisdom of their investment and size itself wasn’t enough. The next month, production chief Darryl F. Zanuck sent a memo to the studio’s producers and executives:

In February 1953, Fox announced that all new features would be shot and released in CinemaScope. So much was riding on this gamble that the studio need not just provide CinemaScope product, but assure that its subsequent releases showed the system to its best advantage. The exhibitors would need proof of the wisdom of their investment and size itself wasn’t enough. The next month, production chief Darryl F. Zanuck sent a memo to the studio’s producers and executives:

Effective now we will abandon further work on any new treatment or screenplay that does not take full advantage of the new dimension of CinemaScope. It is our conviction that almost any story can be told more effectively in Cinemascope than in any other medium but it is also our conviction that every picture that goes into production in CinemaScope should contain subject matter which utilizes to the fullest extent the full possibilities of this medium.

This does not mean that every picture should have so-called epic proportions but it does mean that at least for the first 18 months of CinemaScope production that we select subjects that contain elements which enable us to take full advantage of scope, size, and physical action….

For the time being intimate comedies or small scale, domestic stories should be put aside and no further monies expended on their development. The day will undoubtedly come when all pictures in this category will probably be made in CinemaScope. But in the present market we want to show the things on CinemaScope that we cannot show nearly as effectively on standard 35mm film. We have a new entertainment medium and we want to exploit it for all it is worth.

Zanuck’s memo provided the final thrust of an unspoken industry-wide reaction to the declining audiences of the post-War era. Double bills were on the wane and studios were weary of the tiered production system that brought forth many pictures of diverse length, budget, and audience appeal. Everything cost more money and the marginal returns on smaller films were increasingly unattractive. The blockbuster mentality truly begins here.

CinemaScope made this transition literal. Henceforth, every Fox production would be in color, widescreen, and stereophonic sound—a ‘Class A’ spectacle no matter what. Lumpen subjects were out, or contorted into the highest entertainment. Famously, Zanuck pulled the plug on Waterfront, a grimy Elia Kazan-Budd Schulberg production, because it was too ‘intimate’ for Fox’s new system. As On the Waterfront, the 1.85:1 black-and-white production won eight Academy Awards and provided staggering box office returns for distributor Columbia Pictures.

(Not every CinemaScope release hewed to Zanuck’s edict. The mogul himself hosted a turgid 1954 short subject, “The CinemaScope Parade,” which purported to preview future attractions in the new system. With many upcoming properties still tied down in production and not ready for public consumption, this parade consisted almost entirely of dust jackets of books recently optioned by the studio.)

(Not every CinemaScope release hewed to Zanuck’s edict. The mogul himself hosted a turgid 1954 short subject, “The CinemaScope Parade,” which purported to preview future attractions in the new system. With many upcoming properties still tied down in production and not ready for public consumption, this parade consisted almost entirely of dust jackets of books recently optioned by the studio.)

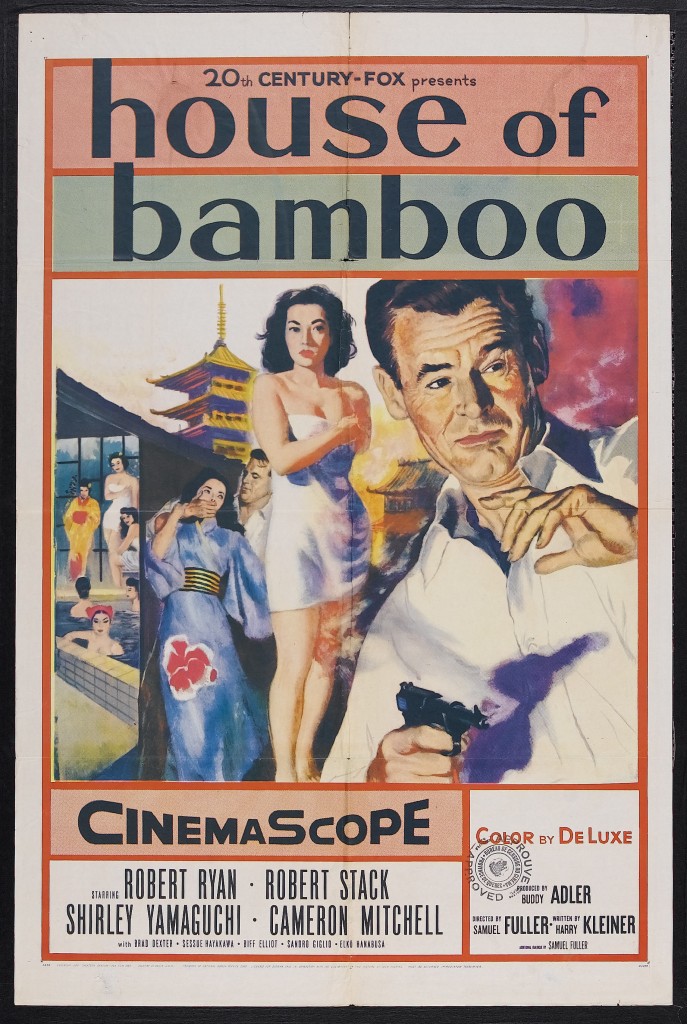

What would 1955’s House of Bamboo look like if not for the advent of CinemaScope? Probably a lot like Fox’s 1948 noir The Street with No Name, of which it’s an all-but-official remake and Oriental transposition. (Harry Kleiner, who wrote the earlier picture, received sole screenplay credit on House of Bamboo, though Samuel Fuller updated and rewrote the entire script, which amounted to ‘additional dialogue’ for studio purposes.)

Conversely, had House of Bamboo been made in 1958, its budget would likely have been much lower, as the imperative to protect and regulate the CinemaScope brand had eased up considerably. By then, Fox had long retreated on its stereo policy, providing prints with standard monaural optical tracks in addition to magnetic playback. Too, M-G-M had released The Power and the Prize, the first monochromatic ‘Scope feature—a middling exercise that would nevertheless pave the way for such masterpieces of the form as The Tarnished Angels, The Apartment, and Last Year at Marienbad. CinemaScope had become a simple shape, not a package deal or an assurance of tony content.

In other words, it’s a pleasant historical accident that House of Bamboo takes the form that it does—a slice of masochistic B-picture pulp briefly inflated to respectable proportions, kind of like a fidgety eight-year-old forced into a suit and tie for an important adult occasion. It’s a film that struggles visibly with ill-judged responsibility.

Fuller in Action

Fuller in Action

The early auteurists made much of director-writer-producer Samuel Fuller as a downbeat primitive, an uncivilized brute turning out folk art on the margins of Hollywood. Fuller’s cock-eyed patriotism, his resistance to allegory, his affinity for violence and sprightly camera movement—all elements that marked him as the true sophisticate’s celluloid cudgel against middle-brow sensibility. “Fuller’s scripts,” Manny Farber wrote in 1969, “are grotesque jobs that might have been written by the bus driver of The Honeymooners.”

If Fuller was the anti-Stanley Kramer, he was also, it must be remembered, a long-striving Hollywood veteran with a brief period of enormous success and respectability in the early 1950s. His low-budget sleeper The Steel Helmet prompted a contract with Fox and the immediate directive to duplicate his Lippert Korean War adventure for the studio. Fixed Bayonets! would be released by year’s end. Fuller’s Fox follow-up, Pickup on South Street, garnered an Academy Award nomination for Thelma Ritter. (There’s a termite performance if ever there was one.) If no one but teenagers and derelicts were following Fuller’s output, as his cultists fantasized, then how did J. Edgar Hoover take notice of Pickup’s allegedly anti-American content?

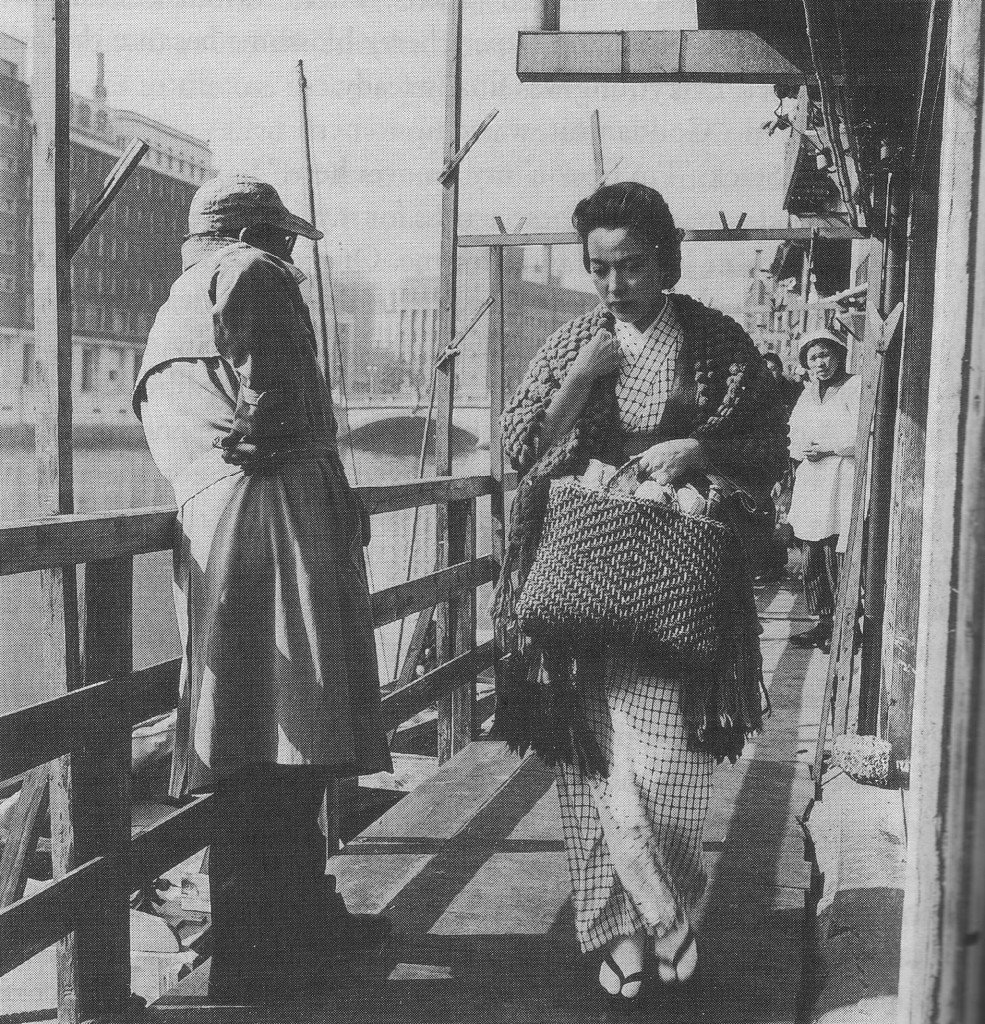

House of Bamboo finds Fuller enjoying the height of Fox and Zanuck’s confidence and backing. Sent to Japan to make the first major studio effort there since the War (RKO had released the low-budget policier backwash Tokyo File 212 four years earlier), Fuller returned with a demented and florid thriller with half-progressive, half-offensive notions of cultural exchange. (Fuller reports in his autobiography that he cast his American stars almost exclusively on the basis of height, wanting tall players to contrast with petite Japanese.)

As a CinemaScope picture, House of Bamboo shows Fuller fielding creative solutions to persistent problems. On the basis of I Shot Jesse James and Pickup on South Street, Fuller might fairly be typed as a close-up man, pushing the camera uncomfortably close to his actors’ faces with a single-minded drive towards big-screen truth. But Zanuck frowned upon close-ups in CinemaScope. Writing to his How to Marry a Millionaire crew in 1953, Zanuck observed:

CinemaScope gives you a certain freedom of movement. Practically everything is lost if two people are huddled together in the center of the screen with nothing but wide open space on each end of the screen.

If the people are spread out filling the screen then we are putting on film an effect that we cannot get on the old 35mm….

CinemaScope didn’t just guide content, but also the whole system of codes and cutting that had developed over the preceding decades. It was an oppressive, corporately-mandated style and one doesn’t strain too badly to understand Fritz Lang’s famous quip about it being best suited to photograph snakes and funerals. (As such, it’s quite miraculous that such relatively early CinemaScope attractions as Track of the Cat, River of No Return, and The Egyptian wound up so expressively coherent and whole.)

Fuller obliges and fills many frames of House of Bamboo with characters end-to-end, but he also plays with depth, conceiving the shots as an ongoing action topography rather than just a dramatic clothesline. (It should be noted, too, that early CinemaScope films play rather differently at home, even in letterboxed copies, with many characters looking puny and distant. The full impact can really only be experienced on the big screen.) There’s also a sense of danger about the film—as if kinky crimes are being imposed at the edges of the picture-postcard documentary reality. The slower editing tempo, rather than burying the action, serves to emphasize it. When Robert Ryan bursts into a bathhouse late in the picture and discharges six bullets in seconds, we never cut away, we never flinch. We’re bound to the proscenium. It has no ready parallels in Fuller’s work or crime thrillers generally.

When declaring Fox’s CinemaScope policy in 1953, Zanuck delivered a great line that really only came to fruition with House of Bamboo: “If CinemaScope does nothing else it will force us back into the moving picture business—I mean moving pictures that move.”

A Note on the Short

Before House of Bamboo’s 1955 release, American audiences very rarely saw anything authentically Japanese on screen; Japanese films like Gate of Hell and Seven Samurai were just beginning to circulate in the West. (Fuller was a major fan of the former.) The War had made Japanese culture anathema to American society—not only on the level of individual, private taste, but as a matter of official government policy.

The short we’re showing before House of Bamboo is perhaps the definitive example of that. “My Japan,” produced by the Office of War Information, is the kind of film that demands an introduction. This propaganda film purports to show one Japanese man’s view of his home country. Suffice it to say, the U.S. Army didn’t send a film crew to Tokyo or ask a real Japanese man his opinion—they plundered shots from Japanese newsreels they had confiscated. They added narration and an introduction that strikes us today, correctly, as racist. The white man in yellow face slurs his speech and makes other half-assed attempts to appear Japanese. He offers a tour of Japan that demonstrates the country’s beauty and its vulnerabilities. His belligerent tone is supposed to incite young American recruits to kill the Japs.

Suffice it to say, we live in a different society today and we’re not trying to incite anyone to firebomb Tokyo. So why show “My Japan” at all? For one thing, it’s an essential preamble to a film like House of Bamboo—it may well have been the only thing about Japan that the average American had seen on screen hitherto. The friction between these cherry-blossom fantasies and Japan as a real, living society is central to House of Bamboo and “My Japan” is a major cinematic source of those racially-tinged, preconceived notions. It’s also the kind of film that would have informed a GI’s idea of Japan—perhaps Robert Stack’s character in House of Bamboo saw it at his induction center before being shipped off during the War.

Finally, “My Japan” is not the work of a private bigot or a studio hoping to cash in on broad caricatures; it’s a film that was made with American tax dollars. It’s the uncomfortable expression of official government policy and, as such, it’s something that we suppress at our own peril. We like showing movies, but, as our mission says, we like showing them in context. Sometimes that context is ugly, but we think it makes the achievement of House of Bamboo all the more impressive.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening “My Japan” and House of Bamboo at the Portage Theater on Wednesday, July 18 as part of its Classic Film Series. Please see our current calendar for more information. House of Bamboo is a brand-new and utterly gorgeous 35mm print from Criterion Pictures USA. Special thanks to Brian Block. “My Japan” is showing in a vintage 16mm from a private collection.