Bill Everson, close friend of many decades, writer, historian and teacher, at a film festival announced that his notion of hell would be to have all the films in the world but no projector. My own hell would be to have a projector and all the films but no one around to see them with me. – James Card

• • •

Last week Drew Hunt, a blogger for the Chicago Reader’s Bleader, voiced an increasingly common attitude towards theatrical movie-going, namely that poorly socialized audience members are so prevalent these days that you may as well not even bother buying a ticket. Such behavior isn’t just confined to The Hunger Games at your local multiplex:

Most of the films I’ve seen in recent weeks have been at either the Gene Siskel Film Center or the Music Box, places where one would assume the audience to possess a certain refinement. However, members of the audience at both theaters weren’t averse to whispering loudly with their friends about things unrelated to the movie, texting, fiddling with their snacks, chewing food loudly, or even falling asleep.

When I really think about it, most theatergoing experiences I have are disrupted by behaviors such as these. Considering this, I’ve drawn the admittedly imprecise but no less eye-opening conclusion that the people who care most about movies are the ones who stay home.

Admittedly, as film exhibitors by trade, we have strong feelings about this subject and about Hunt’s conclusion. Exhibitors are feeling exceedingly under siege these days, and complaints about audience behavior are only a part of it. At a time when the Hollywood studios are gung-ho to migrate their business from traditional theaters to streaming and video-on-demand platforms, strong feelings are unavoidable and necessary.

Admittedly, as film exhibitors by trade, we have strong feelings about this subject and about Hunt’s conclusion. Exhibitors are feeling exceedingly under siege these days, and complaints about audience behavior are only a part of it. At a time when the Hollywood studios are gung-ho to migrate their business from traditional theaters to streaming and video-on-demand platforms, strong feelings are unavoidable and necessary.

The National Association of Theater Owners—a rabidly anti–labor trade group with whom we rarely agree—has done much to fan this paranoid, but not necessarily incorrect, interpretation of recent industry developments. According to NATO, theaters will strike back by screening ‘alternate content’—industry-speak for opera, concert, and sports telecasts. Patrick Corcoran, NATO’s Director of Media & Research, even took to the pages of Boxoffice this month to spin an extended Moneyball analogy about how theaters need to modernize their programming instead of persisting on ‘a tired home run that is still wheezing around the bases a couple of months after it hit the ball.” (But don’t count NATO out on the rude patron front, either; they propose a ‘culture of civility,’ which presumably includes some of the other things that they tout, like ‘auditorium monitoring devices’ and ‘guest response systems.’)

And yet quite independent of this intra-industry fight are routine declarations that film-going is simply dead, often from journalists whose considerable apathy has done much to kill it. Hunt is actually the exception in this respect; at least he saw eight films at the Siskel’s EU Festival. Contrast that with this indiewire article from Jamie Stuart, who proudly proclaims that his sweet HDTV set-up was more than enough to dissuade him from venturing into a theater for the first eleven months of 2011. (And, of course, that’s a sufficient vantage point for him to declare that 35mm is obsolete and that “[s]omeone needs to slap Spielberg in the face and tell him to wake up” about this fact so that history can move forward apace.)

These proclamations are dispiriting chiefly because they frequently manifest a thoroughly anti-social, even misanthropic, attitude towards public spaces and other people. Absent any notion that film is an irreducibly social medium, we’re left screeching about how the friggin’ guy in the next row—the one smacking his lips so loudly on each cashew—is destroying our communion with cinematic art. Can you believe that the woman sitting two seats away simply fell asleep in the middle of the movie? (This is an odd criticism; surely she didn’t come to the movie with the intent to nod off and she certainly didn’t do it to spite you either.)

How times have changed. Until the 1960s, it was expected that people would enter and leave movies as they pleased, regardless of any printed showtimes. (This is the probable origin of the phrase “This is where I came in.”) Theaters have always been chaotic, unruly spaces, unless you believe that children, teens, and many adults were simply less defiantly disaffected in decades past. The grindhouse experience so affectionately remembered today was practically defined by audience behavior that makes texting look positively cordial. (My favorite anecdote from a friend’s recollection of the milieu: a screening interrupted by a fight that culminated in the unforgettable line, “You’re sorry? You’re sorry? You piss on my girlfriend and say that you’re sorry?”)

How times have changed. Until the 1960s, it was expected that people would enter and leave movies as they pleased, regardless of any printed showtimes. (This is the probable origin of the phrase “This is where I came in.”) Theaters have always been chaotic, unruly spaces, unless you believe that children, teens, and many adults were simply less defiantly disaffected in decades past. The grindhouse experience so affectionately remembered today was practically defined by audience behavior that makes texting look positively cordial. (My favorite anecdote from a friend’s recollection of the milieu: a screening interrupted by a fight that culminated in the unforgettable line, “You’re sorry? You’re sorry? You piss on my girlfriend and say that you’re sorry?”)

Above all, the calls for genteel screenings express a strangely anti-septic desire: going out without encountering or being reminded of other people. At best, they’re disruptions or distractions, never positive contributors to the experience.

I frequently find the opposite to be true. Would Hunt have been horrified by the matinee audience with whom I saw The Passion of the Christ for the first and only time? On one side of me, there was a middle-aged woman reflexively screaming “Oh Jesus!” at the bloodier moments. On the other side, a trio of kids, none of whom could’ve been older than nine; one was reading every single subtitle aloud to the other two in a devout whisper. A twentysomething man constantly wept in the row in front of me. Their reactions were distinct from mine and suggested a range of emotions that I could scarcely access or begin to understand on my own. What would I have learned about Gibson’s film or the quite genuine fervor it inspired if I’d caught up with it at home on DVD?

Granted, sometimes audience behavior has nothing immediately to do with the movie at hand. But sometimes this indifference is itself a statement and, in a sense, a form of criticism. If it’s offensive to fall asleep at an art movie, why can’t it be a protest to snooze during the latest violent shoot-’em-up?

There’s another argument in Hunt’s post that demands some unpacking:

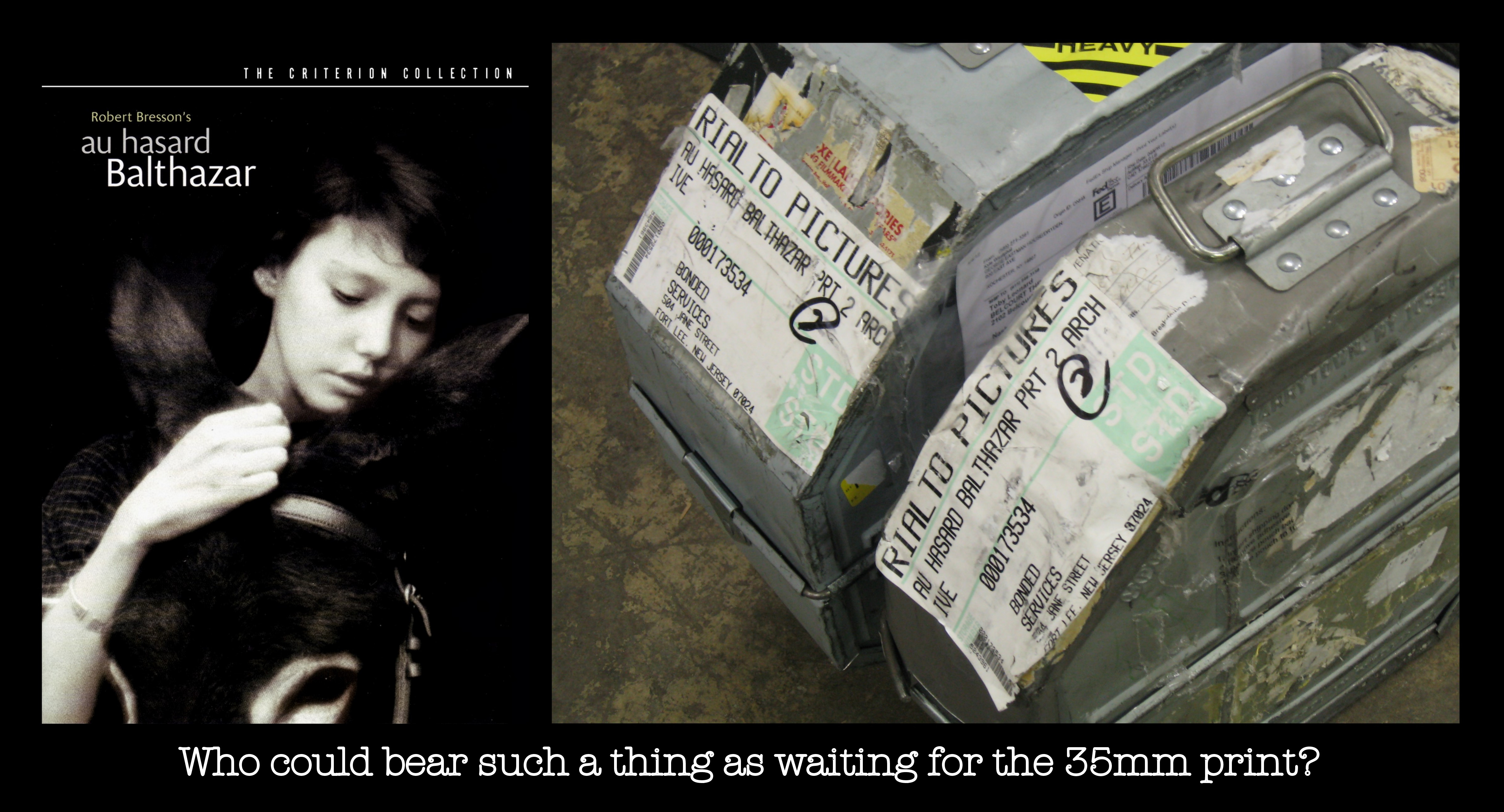

I wasn’t made privy to the allure of cinema until my early 20s, and I feel as if I’ve been playing catchup ever since—which is why I value home viewing as heartily as I do. If I were to delineate percentages for my viewing habits, the results would heavily favor the DVD or streaming format. Without these options, I would’ve missed the pleasure of a plethora of great films. The nourishing experience of, say, Au Hasard Balthazar would have had to wait until the Film Center’s recent Robert Bresson retrospective. Who could bear such a thing?

Considering this, I’d venture to say that home viewing—though certainly not in the intended format—is the more intellectual exercise. To watch a film at one’s leisure, to have the power to pause, rewind, and examine a film, frame by frame, is an invaluable practice.

There is, of course, some truth in this account. Home video is an important research tool and the ability to revisit and dissect films is often essential to writing about them, as we do on our calendar and on this blog. But to elevate that kind of academic viewing experience over the theatrical one is an odd choice. Surely films derive at least some of their power from a sense of internal force and rhythm, an emotional-physical engagement that resists being paused. Imagine an analogous declaration about opera; listening to a CD recording is not just a scholarly adjunct to a live performance, but something that makes the performance nearly superfluous.

There is, of course, some truth in this account. Home video is an important research tool and the ability to revisit and dissect films is often essential to writing about them, as we do on our calendar and on this blog. But to elevate that kind of academic viewing experience over the theatrical one is an odd choice. Surely films derive at least some of their power from a sense of internal force and rhythm, an emotional-physical engagement that resists being paused. Imagine an analogous declaration about opera; listening to a CD recording is not just a scholarly adjunct to a live performance, but something that makes the performance nearly superfluous.

In some ways, Hunt is simply continuing the tradition inaugurated by the Reader’s long-time former film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum. Though sufficiently alarmed by university film programs’ almost-total reliance on home video surrogates in the classroom to devote three pages to this phenomenon in his 2000 manifesto Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Movies We Can See, Rosenbaum quickly came around. Scarcely four years later, he would speculate in his Reader column that “the most meaningful film watching in this country in 2003 was done at home.” In his more recent articles, Rosenbaum has embraced economically destructive bootlegs as the future of cinephilia, with the theatrical model derided as an out-moded paradigm.

Out-moded or not, repertory screenings are bound productively by time and place. Yes, that might mean waiting a few months or years to see Au hasard Balthazar, but that’s the point. The wide dissemination of great films is a positive thing for scholarship, but there’s value, too, in screenings that are themselves social events—things that people actually make plans to see and experience together. The San Francisco Silent Film Festival’s recent ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ presentation of Abel Gance’s Napoleon is an extreme case-in-point: the full orchestra, the Polyvision triptych, the latest iteration of a restoration that required the cooperation of a number of parties to reach the screen.

This logic applies to less rarified screenings, too. Public screenings allow people to see films whose rental and shipping would be prohibitively expensive on an individual basis. Again, this is a positive thing; in the very least, it acknowledges the fact that the conservation and preservation of film history requires a considerable investment, both monetarily and ideologically. Sometimes one simply has to wait for the stars to align. Is this an elite position? No more than the belief that supporting local businesses is essential to sustaining vibrant communities. One should always leave a screening feeling proud to be alive on this spot, in this moment.