When Reds was released in late 1981, its admirers tended to downplay its political dimension. It was a sweeping romance that happened to be about Communists—a perhaps necessary bluff (or a revealing delusion) after American politics had taken a sharp swing towards the right. “It is that personal, human John Reed that Warren Beatty’s ‘Reds’ takes as its subject,” Roger Ebert assured us, but not without cautioning that “there is a lot, and maybe too much, of the political John Reed as well.” Andrew Sarris, who had frequently used his Village Voice perch to mock routinely liberal movies, finally found one he could get behind. “Reds is more a love story than a revolutionary chronicle,” Sarris wrote, “and as it happens, I prefer love stories to revolutionary chronicles.”

When Reds was released in late 1981, its admirers tended to downplay its political dimension. It was a sweeping romance that happened to be about Communists—a perhaps necessary bluff (or a revealing delusion) after American politics had taken a sharp swing towards the right. “It is that personal, human John Reed that Warren Beatty’s ‘Reds’ takes as its subject,” Roger Ebert assured us, but not without cautioning that “there is a lot, and maybe too much, of the political John Reed as well.” Andrew Sarris, who had frequently used his Village Voice perch to mock routinely liberal movies, finally found one he could get behind. “Reds is more a love story than a revolutionary chronicle,” Sarris wrote, “and as it happens, I prefer love stories to revolutionary chronicles.”

The detractors tended to agree with the brunt of this assessment, but understandably saw this as a liability. Pauline Kael called it “the least radical, the least innovative epic you can imagine” and the Soho News corrected the record with “What Reds Won’t Tell You About Louise Bryant.” It was a movie about John Reed that even Reagan could love—and indeed, he did. One can easily imagine him nodding along with Beatty’s Reed as he denounces Zinoviev for his individual-annihilating, freedom-denying brand of Communism.

Paramount’s 2006 small-scale reissue of Reds clearly addressed a shift in the political landscape. The trailer for the DVD positioned Reds as a blockbuster rendition of a prototypical Daily Kos diary, fired up with indignation over an illegal war and a dissent-crushing mainstream. Implicitly, Reds inaugurated a tradition that now included such softly provocative left-wing cinema-events as The Constant Gardener and Syriana.

Do we yet have the tools and sobriety to reckon with Reds? Its technical achievement is unimpeachable. There’s a moment early on in Reds when Bryant buttonholes Reed for an interview after his very brief speech at Portland’s Liberal Club. When can we talk? “Now,” and editors Dede Allen and Craig McKay cut on that word, that syllable to a scene in her apartment. The whole movie has this clipped quality, all tumbling out and jammed up together in a rush of decisions and judgments. In a sense, Reds feels like the culmination of the Resnais-influenced, half-glance New Hollywood editing style that Allen herself initiated in Bonnie and Clyde. Reds is the movie that fashions a working and supple grammar out of it. Nothing carries the appearance of classical cross-cutting here, even when that description is perfectly apt—the shots seem to hover, always looking stitched together and brittle, as if the whole edifice will atrophy when the music stops.

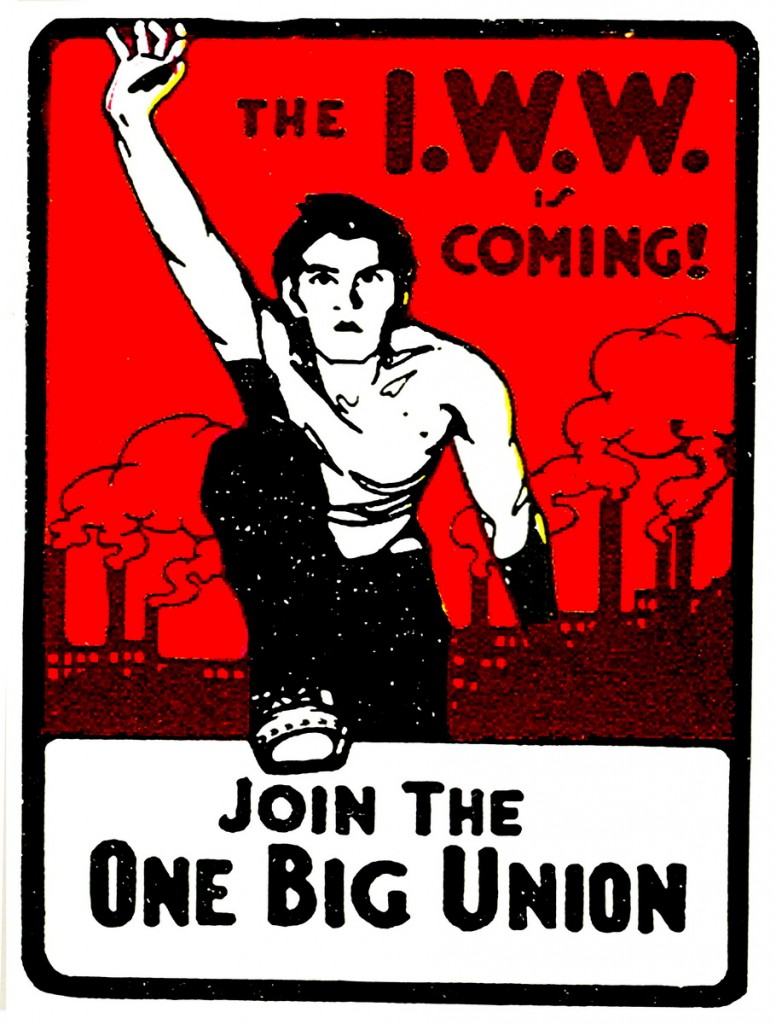

(Less remarked upon is the still-staggering level of background knowledge that Reds assumes from its audience. It’s a long movie with little conventional exposition that simply presumes that viewers already have a basic familiarity with Pictorialist photography, the Armory Show of 1913, the IWW, Eastern European geography, and the distinctions between assorted Socialist/Communist/leftist factions in America and abroad. More radically, Reds also suggests that these things are often and intimately related, a continuum of thought.)

(Less remarked upon is the still-staggering level of background knowledge that Reds assumes from its audience. It’s a long movie with little conventional exposition that simply presumes that viewers already have a basic familiarity with Pictorialist photography, the Armory Show of 1913, the IWW, Eastern European geography, and the distinctions between assorted Socialist/Communist/leftist factions in America and abroad. More radically, Reds also suggests that these things are often and intimately related, a continuum of thought.)

The main story is also constantly interrupted by the troubling testimonies of ‘The Witnesses’—the elderly bohemians and gadflies scooped up by Beatty and his researchers through a nationwide dragnet of classified newspaper ads. Sitting in front of a black screen, they recount what they did and didn’t know about Reed and Bryant, misremember, repeat, contradict one another, sing. Cumulatively, they lend an air of Borsch Belt irreverence to history.

Perhaps we needed an intervening thirty years of televised documentaries to appreciate the radicalism of Reds. Its interviews superficially resemble those of endless history buff cable programming, but the departure is crucial. The Witnesses’ words rarely connect with the action on-screen and no speaker is identified by name, except in the opening and closing credits. Rather than ratify the facts and move the narrative along, they confuse and coerce it towards an aggressively intimate meander. Their anonymous voices are too discordant to be a chorus, obviously authentic but vaguely inscrutable.

The immediate cultural legacy of Reds—Woody Allen’s misformulated appropriation and parody of this structure in his 1983 Zelig—cannot begin to approach the seriousness of its source. When everything becomes a winking fiction, where’s the space for tension and divergence? (Unlike Peter Jackson and Costa Botes’s great hoax Forgotten Silver, Zelig never goes so far as to implicate the documentary form itself as a crucial means of disseminating misinformation.) It’s fitting here to note, as well, that the Laurent Bouzereau-produced Witness to ‘Reds’ making-of documentary that appears on the DVD and Blu-ray release of Reds goes a long way towards illustrating the value of Beatty’s approach. Several interviewees note that sharing memories of the movie on the skimpy, non-descript set calls to mind the testimonies of the original Reds Witnesses—but captions always inform us who’s speaking and there’s little disagreement on tap. Even capitalist magnate Barry Diller insists that everyone from the studio chiefs on down were on the same page, valiantly unafraid of any political controversy! (Everyone except Diane Keaton, whose non-participation in the retrospective cannot help but undercut the consensus Bouzereau strives to fabricate.)

Rare for a Hollywood film and rarer still for an epic one, Reds operates with the assumption of multiple strands of consciousness and simultaneous channels of empathy. Frequently, we’re not even sure who’s speaking or remembering or thinking. Reds continually interrogates its own designs and interpretations, not least with the central Reed-Bryant relationship. It can emphasize Reed’s charisma (it’s a productive limitation that Beatty largely conceives and interprets Reed as a movie star whose worst nightmare is a fickle audience) while acknowledging his inability to understand the roots or soundness of a feminist critique of the prevailing social order. That he cannot recognize, much less renounce, his own complicity in this injustice is the major human tragedy of the film.

Rare for a Hollywood film and rarer still for an epic one, Reds operates with the assumption of multiple strands of consciousness and simultaneous channels of empathy. Frequently, we’re not even sure who’s speaking or remembering or thinking. Reds continually interrogates its own designs and interpretations, not least with the central Reed-Bryant relationship. It can emphasize Reed’s charisma (it’s a productive limitation that Beatty largely conceives and interprets Reed as a movie star whose worst nightmare is a fickle audience) while acknowledging his inability to understand the roots or soundness of a feminist critique of the prevailing social order. That he cannot recognize, much less renounce, his own complicity in this injustice is the major human tragedy of the film.

‘What as?’ Bryant asks when Reed suggests she accompany him to New York. This is the deeply political question that Reds asks, and not just about Bryant and Reed. Continually the characters struggle to live up to their own political ideals; they contend with their own complex relationships to pre-conceived ideas of sex, marriage, domesticity, art, and integrity, never quite steely enough to will themselves a set of completely enlightened desires. On some level, they realize that building a new world from the ashes of the old requires self-immolation.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Reds in a 35mm print from Paramount Pictures on Wednesday, March 21 at the Portage Theater. For more information, please see our current calendar. Please note that we will be starting earlier than usual at 7pm to accommodate the unusual length of Reds.