Those of us who put in full-time hours (and often more) in the repertory cinema game are sometimes apt to lose sight of just how limited our ‘specialty aud’ looks these days. Old movies, once a staple of theater bills, are now relegated to a handful of screens. When was the last time a studio even attempted a major re-issue push, 3-D retrofits of The Lion King and The Phantom Menace excluded? In 1998, Paramount released a 20th Anniversary edition of Grease to over 2,000 screens. In 2010, the same studio bowed a re-tooled Sing-a-long version (much superior, incidentally, and rather a brazen act of corporate graffiti aimed squarely at one of the company’s blandest evergreens) in a dozen theaters and wound up grossing barely two percent of the ’98 take.

Those of us who put in full-time hours (and often more) in the repertory cinema game are sometimes apt to lose sight of just how limited our ‘specialty aud’ looks these days. Old movies, once a staple of theater bills, are now relegated to a handful of screens. When was the last time a studio even attempted a major re-issue push, 3-D retrofits of The Lion King and The Phantom Menace excluded? In 1998, Paramount released a 20th Anniversary edition of Grease to over 2,000 screens. In 2010, the same studio bowed a re-tooled Sing-a-long version (much superior, incidentally, and rather a brazen act of corporate graffiti aimed squarely at one of the company’s blandest evergreens) in a dozen theaters and wound up grossing barely two percent of the ’98 take.

The dedicated repertory house is practically invisible to the industry and the general public. I think it’s fair to say that the repertory business received its widest airing ever in 2005 when Rush Limbaugh incredulously informed his substantial dittohead radio audience of an incident first reported by the Washington Times: a recent screening of Don Siegel’s 1964 version of The Killers at UCLA Film & Television Archive had roused the “prestigious crowd of actors, actresses, writers, reviewers, scholars, researchers and film preservationists” (i.e., a leftist cabal!) to cheers when gangster heavy Ronald Reagan was shot and killed on-screen. The same crowd also booed Reagan’s name in the opening credits, though a band of Reagan supporters provided some counterrevolutionary applause. Would that every Don Siegel retrospective attract this level of media attention.

In a more sympathetic context, last week’s Atlantic devoted a column to the plight of repertory theaters in the digital age. This topic has received only cursory treatment thus far. Many articles have focused on the digital conversion’s effects on ‘mom and pop’ theaters—independent operations that often show a narrow selection of blockbuster films otherwise available in five or six local multiplexes. The industry-wide switch from 35mm to DCP (Digital Cinema Package) exhibition is expected to be completed in the next two years, with theaters not sufficiently capitalized to finance the transition effectively forced to close up shop. These exhibitors are clinging to 35mm because it allows them to use existing projection equipment with minimal and rather predictable maintenance costs. It’s an incidental objective.

Showing films in 35mm is a mission on a different level of magnitude for repertory venues. The programmers and projectionists and theater managers who work at these venues often believe that viewing a film in its original medium is intrinsically bound up with any claim to appreciating or understanding that film. Usually these arguments have to do with a nebulous sort of authenticity—the “film look” that partisans find lacking in “cold” digital presentations. We seem no closer to resolving this debate but not for lack of vocabulary: we have countless metrics of comparison (colorspace, pixels counts, contrast ratios, foot lamberts, etc.) that have, so far, done little more than convince people of the positions they hold already.

Showing films in 35mm is a mission on a different level of magnitude for repertory venues. The programmers and projectionists and theater managers who work at these venues often believe that viewing a film in its original medium is intrinsically bound up with any claim to appreciating or understanding that film. Usually these arguments have to do with a nebulous sort of authenticity—the “film look” that partisans find lacking in “cold” digital presentations. We seem no closer to resolving this debate but not for lack of vocabulary: we have countless metrics of comparison (colorspace, pixels counts, contrast ratios, foot lamberts, etc.) that have, so far, done little more than convince people of the positions they hold already.

Put all this aside for a moment and instead consider 35mm and what it means for programming. Most people (including me some years ago) tend to think that putting together a repertory calendar simply involves a programmer picking a selection of her favorite films. Every night is either a masterpiece or a personal favorite and the thing that winds up on screen is a more or less uncompromised and uncomplicated expression of somebody’s taste. If you can name a film, you can pick up the phone and arrange a playdate.

Though this scenario has a tinge of narcissistic appeal, the reality of the situation is actually far more compelling. Simply stated, the entire history of cinema is not available for public viewing in any given format. Some films are irrevocably lost altogether, victims of neglect or outright destruction. Other films still circulate on 35mm, whether it be in tattered original copies, newly restored ones, or something in between. Many of these 35mm titles are not of sufficient commercial interest to justify the production, marketing, and inventory costs associated with conventional DVD and Blu-ray releases. (Increasingly, niche-driven manufactured-on-demand discs like the Warner Archive imprint have supplanted retail releases of library titles, but these receive a fraction of the public attention that brick-and-mortar discs once did.) Still others are near-impossible to obtain in 35mm prints these days, even though decent Blu-rays (often mastered from extant 35mm pre-print material) are widely available.

The reasons for this inconsistency of availability are often prosaic. Perhaps a foreign film was licensed for American distribution for seven years and the contract dictated the destruction of all stateside 35mm prints at the end of the term should the rights not be renewed. A print reaches the end of its natural life, or one particularly negligent venue prematurely but irrevocably damages the last circulating print of a given title. Perhaps a print sat in a warehouse untouched for decades because a systematic evaluation of its chain of ownership and value looked more daunting than familiar inertia. A studio might restore a film in its library and commission a new print to show off its investment or merely to evaluate the quality of the new duplicate negative. (After all, how can you know whether you’ve made a good negative without at least making a positive test?) Conversely, a studio may own the copyright to a film but not hold any physical assets, which have been conserved in the vaults of a non-profit film archive. An archive may possess a copy of a film, but not realize the uniqueness of the title or not even be aware they possess it due to a run-of-the-mill cataloging error. When all else fails, there’s probably a private collector out there who has a print (but don’t ask him where or how he got it!).

In short, this is a minefield. Not for nothing do I often declare one of the most important parts of programming to simply “know where the bodies are buried.” Sometimes even a glance at the layers and layers of old labels on a single film canister reveals decades of varied use.

At first blush, this chaos would seem a compelling argument for the digital exhibition of repertory titles. The venue books a title and that’s that—no potential to receive a ruined print, no need to overnight the print to another venue because of a tight turnaround, no conflict when two venues want the same print on the same date. Some studios, notably Sony, are demonstrating an admirable effort to make key repertory titles available in DCP (as well as 35mm). Others are, as the Atlantic reported, simply instructing programmers to go out and buy a DVD at the supermarket like any other schmoe.

And therein lies the problem. The digital future always looks brighter than what we have now. (And why shouldn’t it? It’s the future, after all.) We can complain about a given title being unavailable in 35mm—but the prospect of a studio spending a sizable amount preparing a 2K or 4K master for that same movie isn’t encouraging either. Inevitably, titles will slip through the cracks and the promise of a slightly scratched 35mm print will look mighty enticing.

But there’s also a larger issue here about what repertory programming is. A world where our film history is found on a server or the cloud or the palm of your hand resembles nothing less than the generic rock radio pre-programmed from a very narrow Clear Channel playlist.

Not everything is readily available in 35mm, and that’s a large part of the art of programming. Many programmers book titles they don’t necessarily like because a new 35mm print is making the rounds and the community-sustaining value of supporting the brave few striking new 35mm prints outweighs any personal misgivings. (Next season, we have the good fortune to be presenting a new 35mm print of a film we do like quite a bit from our friends at Criterion Pictures USA: Samuel Fuller’s House of Bamboo.) At other times, you book a 35mm print because it will only be available for a very brief window of time before, say, returning to France for the foreseeable future. It’s about operating under constraints, but constraints that enrich and challenge and ultimately desecrate our individual biases.

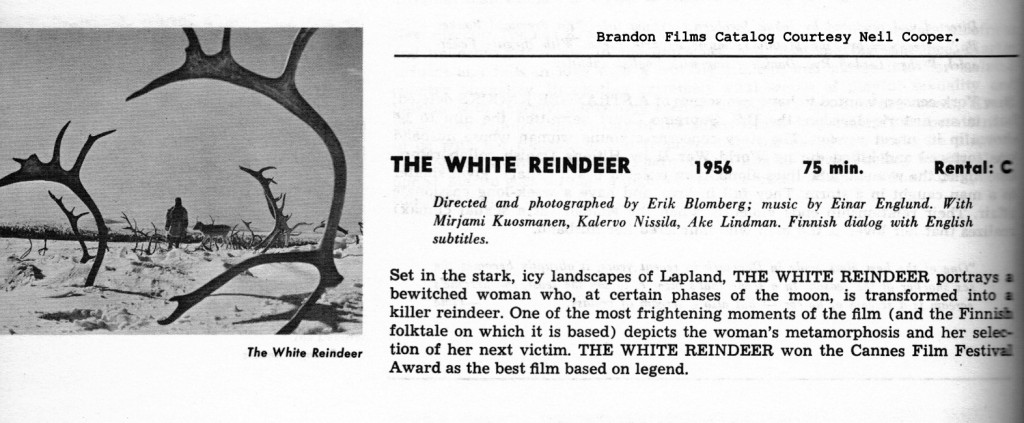

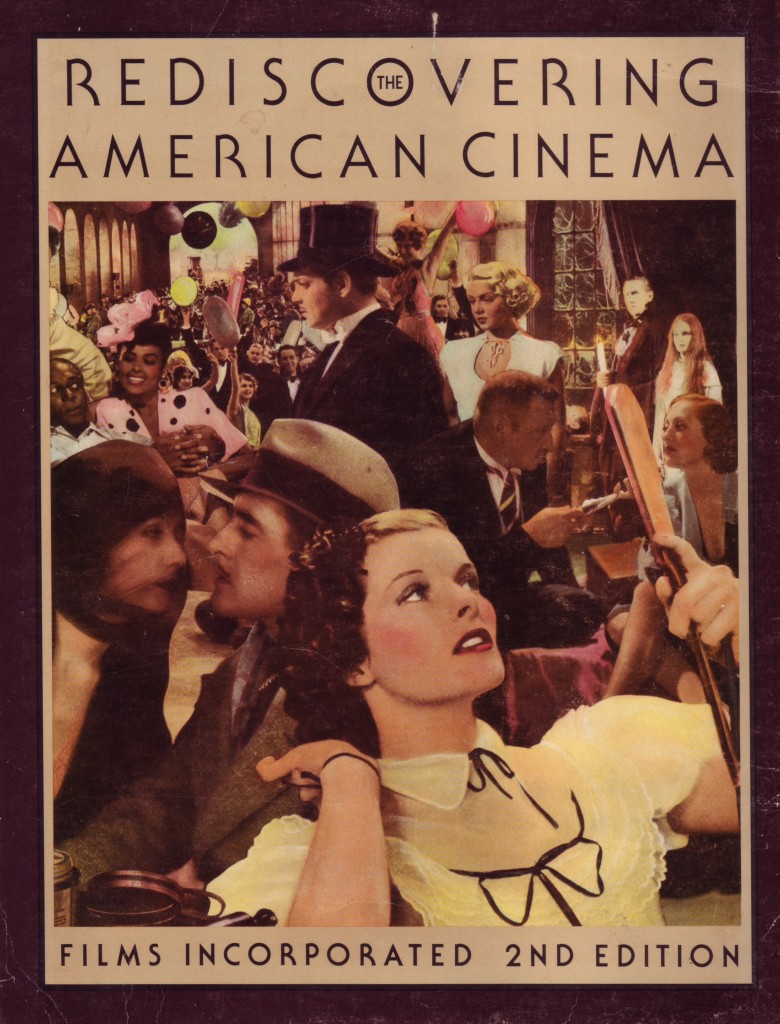

To program a great calendar in 2012 would be different from programming a great one in 2002 or 1982—the archaeological aims shift and the calendar itself becomes a document of what was within reach and worth recognizing and resurrecting at a given moment. Reading through old distribution catalogues, like Films Inc.’s Rediscovering the American Cinema or any Brandon Films directory from the 1950s, disrupts easy assumptions about the supposedly provincial tastes of previous generations; many unadorned (and infrequently booked) titles from 16mm catalogues past would look like inspired coups of programming today. (Last season’s Valkoinen peura is a perfect example—this beachhead for a never-realized Finnish art house wave was hiding in plain sight.)

Let’s examine this season’s calendar and you might get a better idea of what we’re talking about. (I should also mention here that programming duties for NWCFS are shared between Julian and I, and the final line-up reflects a common sensibility and approach.) A Night to Remember is on the calendar as a tie-in with the Titanic centennial. It’s a British film produced by the Rank Organisation. Home video rights in the US are held by the Criterion Collection, but its parent company, Janus Films, doesn’t have theatrical rights. MGM, now managed by Park Circus, has a few prints and we were frankly shocked they weren’t all booked at the time that Julian made our request. Maybe the somewhat convoluted chain outlined above kept folks away.

Programmers crib off each other, too. (It’s not exactly cribbing, though; the economics of this game wouldn’t work very well if people refused to book a print just because someone else had already shown it.) Back Street is a foundational melodrama and an essential part of Universal’s history, though we can’t remember the last time it screened publicly in Chicago. I saw it in a private classroom screening that I crashed in 2006 and have been waiting for a chance to show it ever since. So’s Your Old Man was recently added to the National Film Registry, but it’s not common. I first saw it at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival in 2009. I caught the Library of Congress’s 35mm print of Give Us This Day when it screened as part of the Rochester Labor Council’s annual series at the Dryden Theatre the year before. All of these were treasures that we wanted to share with a wider audience. And sometimes there are films we book because we want to see them, too, like …one third of a nation…; we were tipped off to the Library of Congress’s preservation when it showed up on a Turner Classic Movies schedule last year.

Programmers crib off each other, too. (It’s not exactly cribbing, though; the economics of this game wouldn’t work very well if people refused to book a print just because someone else had already shown it.) Back Street is a foundational melodrama and an essential part of Universal’s history, though we can’t remember the last time it screened publicly in Chicago. I saw it in a private classroom screening that I crashed in 2006 and have been waiting for a chance to show it ever since. So’s Your Old Man was recently added to the National Film Registry, but it’s not common. I first saw it at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival in 2009. I caught the Library of Congress’s 35mm print of Give Us This Day when it screened as part of the Rochester Labor Council’s annual series at the Dryden Theatre the year before. All of these were treasures that we wanted to share with a wider audience. And sometimes there are films we book because we want to see them, too, like …one third of a nation…; we were tipped off to the Library of Congress’s preservation when it showed up on a Turner Classic Movies schedule last year.

It also comes down to studios sometimes. Universal does truly outstanding work in preserving and circulating both their own library and the 1929-1949 Paramount titles. We make a point of supporting their efforts by booking their titles. This season we have 35mm prints of old chestnuts like Sullivan’s Travels, but also rarer items like Angel and Back Street from Universal.

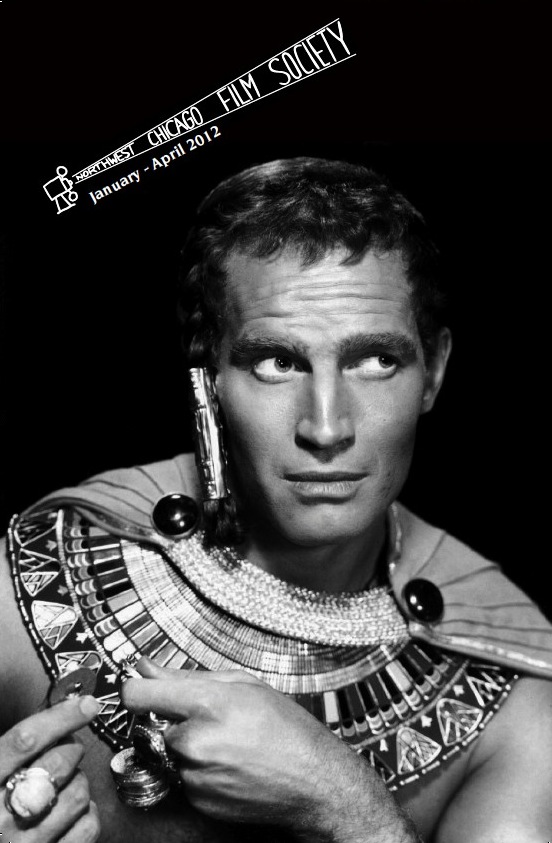

Some other slots are filled more colorfully. We put Liebelei on the calendar after a collector friend in California bragged about scoring a 35mm print. Another collector we know has wanted to publicly screen his original 35mm IB Technicolor dye transfer print of The Ten Commandments for a goodly long time; we were taken with the suggestion, especially because the prints of Commandments that circulate through conventional channels these days are improperly cropped. In more ways than one, the 1956 theatrical experience of Commandments is largely lost to us, so this would make for a truly unique screening. Another print wound up on the calendar only after Becca and Julian fished it out of a dumpster. (We can’t say which one out of respect to the dumpster.)

We had never heard of Turn the Key Softly before a listing for a vintage 35mm print appeared on eBay. It turned out to be as good as we’d hoped it would be and it provided a note of extreme rarity and non-American origin to the calendar. These days we have a few loose rules about our calendars: there has to be at least one western, one musical, a foreign film, an independent production, a few titles most definitely not available anywhere else. The calendar practically programs itself. But the rule about the western is the most important.

The long-term stability and support for this model of programming is precarious. Next month New York’s Film Forum, the most influential rep house in America, will be running a week-long sidebar called ‘This is DCP,’ which argues in its own non-committal way for the integrity of digital presentations of classic films. “But is watching a DCP the same experience as watching a film print?” asks Film Forum. “The jury is still out, so for this one-week series, we’ve chosen the crème de la crème of classics on DCP …. You be the judge.” (If repertory goes digital, it will your prerogative, not Film Forum’s.) Of course, most repertory houses and their audiences won’t have that luxury, as the verdict is, for the most part, economically determined. Those who can afford DCP will likely come around to its virtues and validity quickly enough. Very few venues and screening series are specifically, incontrovertibly dedicated to presenting film-on-film. Our friends at the aptly-named Film on Film Foundation in Berkeley are one notable exception. We aren’t much interested in showing anything but film, either—it wouldn’t be nearly as fun.

The long-term stability and support for this model of programming is precarious. Next month New York’s Film Forum, the most influential rep house in America, will be running a week-long sidebar called ‘This is DCP,’ which argues in its own non-committal way for the integrity of digital presentations of classic films. “But is watching a DCP the same experience as watching a film print?” asks Film Forum. “The jury is still out, so for this one-week series, we’ve chosen the crème de la crème of classics on DCP …. You be the judge.” (If repertory goes digital, it will your prerogative, not Film Forum’s.) Of course, most repertory houses and their audiences won’t have that luxury, as the verdict is, for the most part, economically determined. Those who can afford DCP will likely come around to its virtues and validity quickly enough. Very few venues and screening series are specifically, incontrovertibly dedicated to presenting film-on-film. Our friends at the aptly-named Film on Film Foundation in Berkeley are one notable exception. We aren’t much interested in showing anything but film, either—it wouldn’t be nearly as fun.

This post is part of an ongoing series about the consequences of the current wholesale conversion of cinema exhibition from film projection to digital presentation. Read our earlier entries here, here, and here.