Recently, David Bordwell devoted a post on his blog to a crucial but undervalued question: where do you sit in the movie theater?

Speaking for myself, I can’t fathom sitting anywhere but the first five or six rows, making some allowance, of course, for the design of the space. Many first and second row seats are too close, placed by bottom-line-minded corporate architects without any thought towards whether the full width of the screen is visible without distortion. The further one gets from the screen, the more the show begins to look like television, with comparable distractions priced into the equation. Much like the preference for watching TV with all the lights on, cinema screens viewed from the back of the auditorium tend to get lost in a mess of ambient light—exit signs, aisle markers, foyer spillover. There are definite, cheerfully imposed barriers between your body and the image. An anti-engagement.

Naturally, this taste makes for awkward social occasions. You try to describe your preferences in a non-incriminating way, waving towards the screen and simply saying that you like to sit close. Most people take this to mean ten rows from the back rather than five. How do you compromise with a compromise?

On the rare occasion that a back-row regular is coaxed towards the front, the results are usually violent, a constant mélange of bewilderment and complaint. In college, a group of us students sat in the first row at every show; one night we were joined by the spouse of an instructor. She thought we were crazy but vowed to give it a shot. Unfortunately, she picked the wrong movie for this experiment—a pristine 35mm print of Shock Corridor from UCLA, a highly assaultive work in its own right, made all the more assertive seen from that vantage point. It was terrifying. The next night she returned to her usual spot.

In some ways, of course, Shock Corridor is absolutely the right movie to test the front-row hypothesis. The full effect of that film, or Fuller’s earlier Underworld U.S.A. or Dreyer’s La passion de Jeanne d’arc, can only be garnered from the front; the gigantic close-ups, viewed from the middle of the theater, register as standard-issue film grammar rather than the uncomfortable intimacy they yearn to create.

Of course, for people who make their livings projecting films, the front row is rarely an option. At first blush, the projection booth is the very worst place to watch a movie. There’s an undifferentiated sea of white noise from the exhaust, the rectifier, the projector motor, the lamp house; the soundtrack is often heard through a tinny (and monaural) monitor speaker; viewing ports are rarely designed with enjoyment of the show in mind, with some not even providing a good view of the entire width of the screen; and the task of threading, rewinding, changing over from one reel to the next suggests debilitating distraction.

Some projectionists solve this conundrum by simply not liking, or at least not caring much, for movies. It’s just a job. (This is something of an understandable position: can you imagine projecting the road show presentation of The Sound of Music day-in, day-out for two years straight, a very real fate for many small-town projectionists of an earlier generation?)

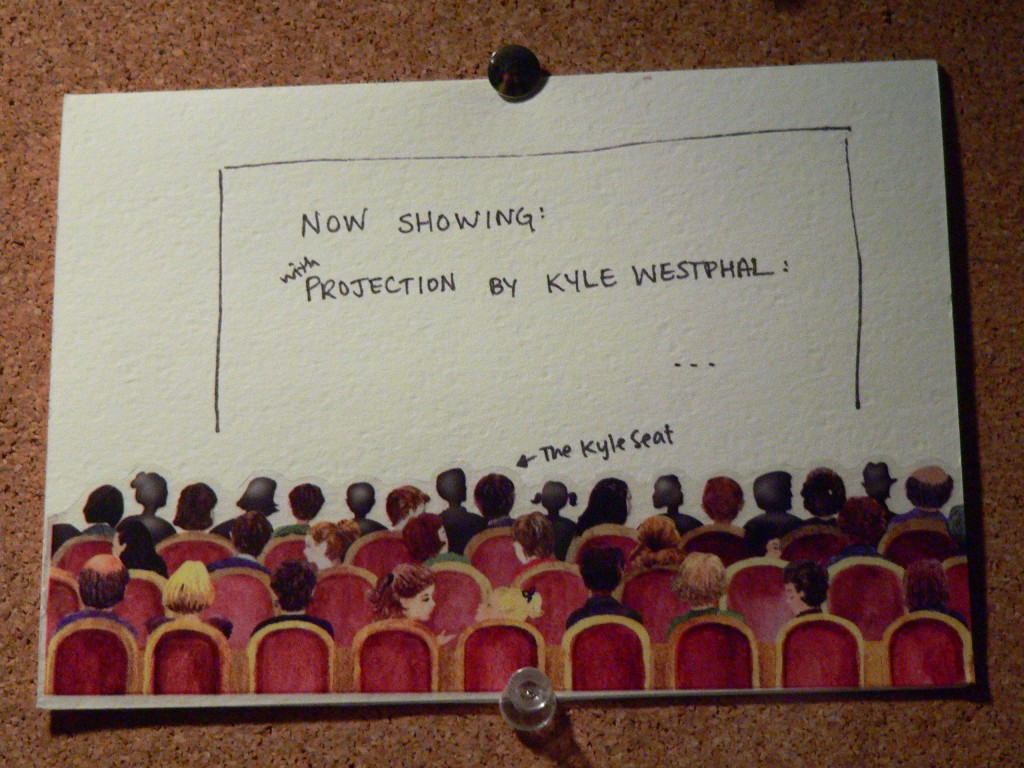

But for some of us, this is an antithetical position. We handle this stuff all day long and cannot imagine not feeling connected with it. The notion that we could project films and not really see them or think about them would exemplify a supremely alienated kind of labor. (“Oh, I never saw that one. I just projected it.”) To be sure, watching a film from the booth requires some caveats—and not small ones, at that—but caveats should not be confused with limitations. In fact, the projection booth constitutes a radical seat for viewing cinema.

I projected that movie, I know it well.

First off, projecting suggests the movies are not primarily narrative vehicles. When you lace up the reel, adjust the framing, check the thread path, you invariably miss bits and pieces. You’re not entirely sure about which character is which, or their precise relationships to one another. Rather than being an unsatisfying or incomplete experience, projecting forces a re-orientation of what makes up a movie.

The mechanics of the job already suggest a partial answer. Generally speaking, it makes the projectionist an active participant in the craft of filmmaking. A good projectionist is constantly monitoring focus and framing, hyper-attenuated to any fluctuations or mistakes, although most are imperceptible to the audience. It’s a hard, physical awareness of the frame as a unit of construction, one that can be unbalanced or incorrect. It gives solidity and consciousness to borders and lines that are otherwise made indistinct by the masking, curtains, and darkness of the auditorium.

The mechanics of the job already suggest a partial answer. Generally speaking, it makes the projectionist an active participant in the craft of filmmaking. A good projectionist is constantly monitoring focus and framing, hyper-attenuated to any fluctuations or mistakes, although most are imperceptible to the audience. It’s a hard, physical awareness of the frame as a unit of construction, one that can be unbalanced or incorrect. It gives solidity and consciousness to borders and lines that are otherwise made indistinct by the masking, curtains, and darkness of the auditorium.

(Many contemporary prints are stuck with the full height of the frame exposed on the print, but with the intent that the projectionist will crop the image to an aspect ratio of 1.85:1 using an aperture plate in the projector gate. Framing such a print incorrectly often reveals boom mics and the like to the audience—a remarkably sloppy mistake that cinematographers simply trust projectionists not to make.)

Focus is something else. Once the projectionist has established that the film is not warped, that it’s traveling through the projector gate smoothly, that the lens mount is steady, then the film itself becomes a play of focal planes. You realize intuitively which movies possess a narrow depth of field by design, which ones would appear to be out-of-focus but for the fact that you know damn well they aren’t because you set the lens yourself. You’re immediately aware of variations in grain structure, the physical building block of cinema.

Change-overs, on the off chance that the theater maintains two projectors rather than one, propose another kind of attention. While waiting for the four frames (i.e., one-sixth of a second) of black dots (or white circles or red slashes or unsightly puke-colored rings), the projectionist is riveted to the screen. To do otherwise would raise the possibility of one reel ending without the motor on the other machine sufficiently up to speed to make a superior and seamless transition between reels. The eyes turn toward the top right corner of the frame. You stop reading the subtitles. You consciously try to ignore any kinetic noise subsuming the rest of the frame. You get nervous as the cutting becomes quicker—don’t the editors know not to place a change-over cue in the middle of a frantic scene where it’s likely to go unnoticed? You judge the pacing and style to be untranquil and upsetting, though the audience is cognizant of no such modulation.

Change-overs, on the off chance that the theater maintains two projectors rather than one, propose another kind of attention. While waiting for the four frames (i.e., one-sixth of a second) of black dots (or white circles or red slashes or unsightly puke-colored rings), the projectionist is riveted to the screen. To do otherwise would raise the possibility of one reel ending without the motor on the other machine sufficiently up to speed to make a superior and seamless transition between reels. The eyes turn toward the top right corner of the frame. You stop reading the subtitles. You consciously try to ignore any kinetic noise subsuming the rest of the frame. You get nervous as the cutting becomes quicker—don’t the editors know not to place a change-over cue in the middle of a frantic scene where it’s likely to go unnoticed? You judge the pacing and style to be untranquil and upsetting, though the audience is cognizant of no such modulation.

Films that employ shock cuts are especially enervating. You make the change-over and the first image of the new reel has nothing especially to do with the last image of the reel that preceded it. There’s no continuity. You begin to wonder, even though you checked the head leader three times, whether you did not, in fact, simply thread up the wrong reel, violating the linear progression of the story.

What I’m trying to say is that projectionists possess a characteristic perspective, attuned to films in a unique and particular way. (You can see why a 1927 issue of The Amerian Projectionist campaigned to re-christen the projection booth as the projectatory.) Films possess a level of subliminal style, something invisible to the average viewer but indelibly important to the experience. These are aesthetic considerations so minute and precise to have escaped proper names and considered correlations. It’s something that hangs over the whole film, more substantial than any missed plot point or actorly touch. Projectionists are both dissociated from the films they see and watching them more intently, more queerly, than everyone else.

There’s even a certain kind of film that plays better from the booth, things like Le Quattro volte or The Second Circle that demand a certain kind of concentration difficult to maintain in a nap-friendly theater. Projectionists see motion even when things look still. It’s no accident, then, that projectionists are, on the whole, more sympathetic to the whole idea of avant-garde cinema than many film critics and curators. They’re already watching films in an avant-garde way.

There’s even a certain kind of film that plays better from the booth, things like Le Quattro volte or The Second Circle that demand a certain kind of concentration difficult to maintain in a nap-friendly theater. Projectionists see motion even when things look still. It’s no accident, then, that projectionists are, on the whole, more sympathetic to the whole idea of avant-garde cinema than many film critics and curators. They’re already watching films in an avant-garde way.

Needless to say, this interpretation is based on cinema as a material, specifically celluloid-based, thing. Something that we can manipulate, correct, perfect, and silently maintain, something still susceptible to human intervention and judgment. It would be a pity to lose this radical seat in the digital transition.