Most people talk about movies on the basis of stars, directors, plots, sometimes genres. In some ways, though, the surest indicator of tone, style, and resonance, if not overall quality, is the production company.

Most people talk about movies on the basis of stars, directors, plots, sometimes genres. In some ways, though, the surest indicator of tone, style, and resonance, if not overall quality, is the production company.

Film programmers tend to think about this rather often. More than we like to acknowledge, repertory screenings are dictated by the vagaries of which studios make continued efforts to circulate their titles and which don’t. Booking prints is more complicated than it might sound at first. Keeping tabs on who has what demands a near-encyclopedic command of corporate merger dates, decades-old television licensing agreements, the whereabouts of archival deposits, and individual tastes of collectors and curators long since gone. It’s easy to take for granted today, for example, that a film made by Warner Bros.-First National seven decades ago can be rented directly from Warner Bros.; for a long time, the classic WB titles were held by United Artists Classics, later MGM-UA, subsequently Turner Entertainment, itself now conveniently under the Time Warner umbrella.

It’s easy to forget about studios when the studios themselves made such all-encompassing efforts to divest of their back catalog. RKO’s library traded hands from one disinterested owner (the General Tire and Rubber Company) to another (C&C Television Corp., a cola company subsidiary). Paramount’s 1929-1948 holdings were sold off to an MCA shell-company, EMKA in 1957, with many titles forever after only available in copies that bare the marks of quick, cheap, and frenzied duplication for television distribution. (Luckily, MCA’s subsequent acquisition of Decca Records, itself the parent company of Universal-International, brought the Paramount library under the auspices of a studio that would demonstrate exceptional stewardship of this complex collection.)

Once we find a path through this thicket of malleable ownership, we begin to notice qualities common across a studio’s production schedule. Their form speaks to the ideology. The Warner Bros. picture of the 1930s is, of course, instantly recognizable—rarely more than 75 minutes, rough around the edges, focused so intently on elemental striving that it neglects to notice or much care about the finer things in life. M-G-M’s features of the same period are, with only a handful of exceptions, insufferable—invariably half an hour longer than they need to be, never content to simply show something when it can be spoken, repeated, and hammered home in expository dialogue delivered disarmingly late in the picture. Watching M-G-M output can actively make you angry: so much waste on such pallid, undercooked, but overdetermined material. After the anger subsides, you feel a strange pity: the pictures demonstrate such an enfeebled, narrow notion of class that the monolithic (and conservative) M-G-M house style just sounds tinny.

(The best M-G-M product of the period is either pure aberration—Freaks, Hallelujah!, Mad Love—or a well-oiled example of the small, but quite genuine pleasures, afforded by the studio’s respectable formulae, such as Private Lives or Skyscraper Souls. At the other end of the scale, what other studio could draw upon the talents of Howard Hawks, William Faulkner, and Gary Cooper and produce a film so useless as Today We Live?)

(The best M-G-M product of the period is either pure aberration—Freaks, Hallelujah!, Mad Love—or a well-oiled example of the small, but quite genuine pleasures, afforded by the studio’s respectable formulae, such as Private Lives or Skyscraper Souls. At the other end of the scale, what other studio could draw upon the talents of Howard Hawks, William Faulkner, and Gary Cooper and produce a film so useless as Today We Live?)

Let’s be clear: Paramount produced the most consistently sophisticated and clear-headed film fare in the 1930s and early 1940s. The top-line continental talent roster—Ernst Lubitsch, Josef von Sternberg, Billy Wilder—was matched by a bevy of craftspeople who collectively evinced an overarching sense of taste that easily outstripped M-G-M’s tacky idea of the same. Even when making ‘B’ pictures and lower-budget fare, Paramount’s technicians accorded a baseline standard that was very high indeed. (Compare a ‘minor’ Paramount film like 1932’s Hot Saturday to quickie output of any other studio, and every set-up and edit looks uncommonly professional and considered.) Above all, they’re adult in their concerns and conclusions.

Paramount didn’t do everything well, of course. Its straight melodramas are frequently less urgent, less dangerous than parallel efforts at other studios. (Paramount’s perfectly good 1933 Claudette Colbert vehicle Torch Singer is nevertheless a bedtime story next to Universal’s devastating 1934 version of Imitation of Life.) Its horror films are impressive, but unfocused, really needing the control of a director like Universal’s James Whale to sculpt their disturbing images into coherence. Its Astoria-shot Broadway adaptations occasionally go limp—and then a shot is held a bit longer than you expect and the whole thing takes on an intensity of brutal observation that still grips.

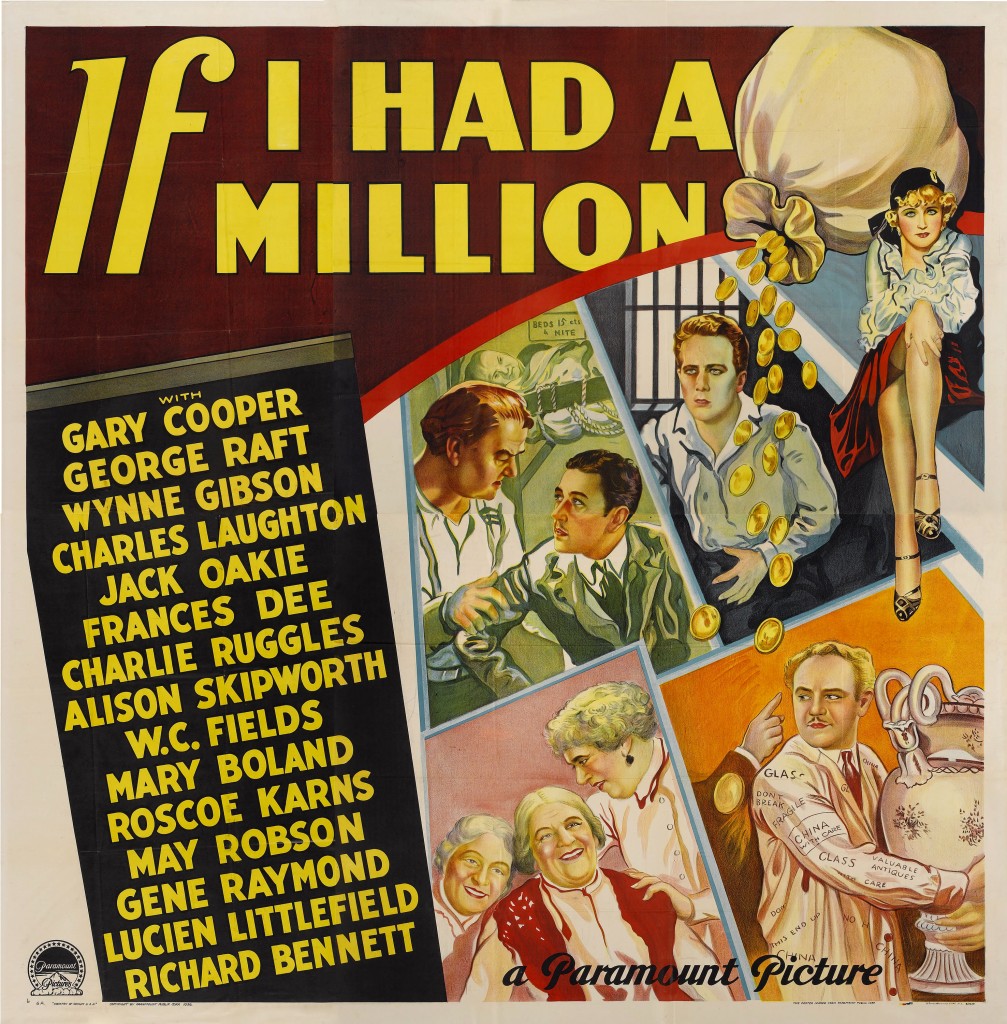

Selecting Paramount’s masterpiece of this period is difficult, though not for lack of plausible candidates (among them, The Wedding March, Docks of New York, Morocco, The Smiling Lieutenant, Trouble in Paradise, A Farewell to Arms, Million Dollar Legs, Duck Soup, The Scarlet Empress, Peter Ibbetson, Make Way for Tomorrow, Midnight, and Christmas in July, to select only a handful). If I Had a Million may not be on the level of those films, but as a representative sample of Paramount’s virtues during the ’30s, it can’t be beat. To some degree, it exceeds and amplifies the usual virtues.

Getting a handle on the planning and production of If I Had a Million during the summer and fall of 1932 is somewhat difficult. A notice in the Film Daily publicized Paramount’s efforts to solicit story material from “50 of the world’s leading writers.” The production was mentioned in the same breath as such obviously serious and industry-uplifting efforts as Strange Interlude. The cast list seemed to be updated every other day. Gary Cooper’s participation was announced barely a week before the film’s Los Angeles preview. A steel magnate decides to disperse his millions to random strangers, and that’s all you need to know.

(Perhaps not the “New Deal in Entertainment” that Warners would soon be offering, Paramount’s publicity nevertheless spoke of the set as a sort of WPA avant la lettre. “A group of old-time stage actresses, many of whom have been ill, unable to work, or actually destitute, found that Hollywood has a heart after all when production of ‘If I Had a Million’ … was underway,” reported the Los Angeles Times. The charity casting included stage and screen veterans like Margaret Mann, Ruby Lafayette, Gertrude Norman, Lydia Knott, Edith Yorke, Ida Lewis, and Emma Tansey. In describing the travails in the final segment set in May Robson’s old folks’ home, the Chicago Daily Tribune struck a particularly cruel vérité note: “It wasn’t acting for a lot of the old ladies, for these things are grim and real things to them. The crying was quite real in this scene, so touching that the director himself had trouble with his eyes.”)

(Perhaps not the “New Deal in Entertainment” that Warners would soon be offering, Paramount’s publicity nevertheless spoke of the set as a sort of WPA avant la lettre. “A group of old-time stage actresses, many of whom have been ill, unable to work, or actually destitute, found that Hollywood has a heart after all when production of ‘If I Had a Million’ … was underway,” reported the Los Angeles Times. The charity casting included stage and screen veterans like Margaret Mann, Ruby Lafayette, Gertrude Norman, Lydia Knott, Edith Yorke, Ida Lewis, and Emma Tansey. In describing the travails in the final segment set in May Robson’s old folks’ home, the Chicago Daily Tribune struck a particularly cruel vérité note: “It wasn’t acting for a lot of the old ladies, for these things are grim and real things to them. The crying was quite real in this scene, so touching that the director himself had trouble with his eyes.”)

The final print boasted eight stories, fifteen stars, eight directors, and no less than sixteen writers. (And those were just the ones credited on screen; undoubtedly others contributed without citation, inclusive of all the cinematographers, assistant directors, editors, and countless other contracted crew given unusually short shrift here.) Exactly who did what behind the camera was left murky at release time. Nearly every contemporary review attributes the Charles Laughton segment to Lubitsch, a fact that Paramount promoted to the exclusion of the other directors’ participation. (It’s an out-sized bit of publicity for the shortest, and most unwaveringly linear, segment.) Some reviews linked specific stories to individual writers and directors, but a measure of ambiguity was preserved. Later critical accounts and filmographies offer divergent answers about who did what and some have devoted considerable space to parsing this question.

This matter of credit is not important for auteurist reasons (is the Charlie Ruggles episode A Film by Norman Z. McLeod or, perhaps by Stephen Roberts?) but for the way it speaks to the overall nature of the production. More than most Hollywood features, If I Had a Million is a corporate product, the result of committee-thought. The exact contributions of its human laborers are purposefully obscure. Its author is Paramount Pictures in a significant way.

It’s bracing, then, that If I Had a Million is not only tonally varied and emotionally measured, but surprisingly reasonable and non-loathsome in its attitude towards money. The critic Dave Kehr has, with justice, characterized contemporary Paramount efforts as fantasies of an ‘Uptown Depression,’ one which ‘seemed to have its greatest effect not on switchboard operators and taxi drivers, but on Park Avenue socialites, Broadway stars and well-heeled bootleggers.’ And yet no one in If I Had a Million instinctively reaches for new minks or sables at news of the seven-figure windfall. If these characters buy stuff, they destroy it willfully and immediately (as in the Fields and Ruggles segments). Nearly all use the money for some act of defiance against illegitimate economic overlords. Prostitute Wynne Gibson’s decision to rent herself a hotel room and sleep alone for the first time in memory is a sly rebuke to ruling forces too diffuse to be dispatched with something like Laughton’s Bronx cheer proffered in the boss’s doorway.

No one in If I Had a Million is delirious from hunger, but their everyday psychological deprivation is acute. This ‘capitalist’ film reflected Depression-era realities and attitudes and pointed towards legitimate grievances that increasingly looked irresolvable through conventional political channels. While If I Had a Million was playing second-run at the Southtown at 63rd and Halstead, the Chicago Defender coincidentally posed a comparable question in its ‘What Do You Say About It?’ column. Most of the hypothetical reader-millionaires wrote of building schools and other high-minded activities, though one Boisey Williams of Chicago proposed a “campaign to debunk the so-called present day Race leaders. In each principal city I would put certain radical leaders on my pay roll to attend all the meetings that are held under the guise of ‘uplift movements,’ and when the speakers begin to sell us to the white people, who are always present for a purpose, one of my associates would ask important questions that would break up the meeting and discredit the ‘sell-out’ leader.”

No one in If I Had a Million is delirious from hunger, but their everyday psychological deprivation is acute. This ‘capitalist’ film reflected Depression-era realities and attitudes and pointed towards legitimate grievances that increasingly looked irresolvable through conventional political channels. While If I Had a Million was playing second-run at the Southtown at 63rd and Halstead, the Chicago Defender coincidentally posed a comparable question in its ‘What Do You Say About It?’ column. Most of the hypothetical reader-millionaires wrote of building schools and other high-minded activities, though one Boisey Williams of Chicago proposed a “campaign to debunk the so-called present day Race leaders. In each principal city I would put certain radical leaders on my pay roll to attend all the meetings that are held under the guise of ‘uplift movements,’ and when the speakers begin to sell us to the white people, who are always present for a purpose, one of my associates would ask important questions that would break up the meeting and discredit the ‘sell-out’ leader.”

Nothing in If I Had a Million approaches that solution, of course; nevertheless, few films are more direct and insightful about hating and protesting your position in society. (It’s also forthright enough to acknowledge that even a million bucks doesn’t go nearly far enough in a rigged police state with other priorities.) Fantasy or not, If I Had a Million is about the same inchoate political dissatisfaction that’s presently driving thousands into the streets of a newly Occupied America.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening a 35mm print of If I Had a Million as part of our Classic Film Series at the Portage Theater on Wednesday, November 23. Print courtesy of Universal, special thanks to Paul Ginsburg and Dennis Chong. Please bring any visiting in-laws and check out our current calendar for more information.