There has always been an artificial divide between cinema and television. The latter, it was prophesized, would bring about the death of the former. Movies quickly embarked on out-flanking TV with innovations like widescreen, stereo imagery (3-D) and stereo sound (four-track magnetic playback), Eastmancolor, and, eventually, sex and violence that would make any network censor blanche. Cinephiles proudly declared they didn’t own a television set and TV buffs shook their heads over the expense and inconvenience of going to the movies. Frank Tashlin satirized this division early on (and hilariously) in The Girl Can’t Help It and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?

Cinephiles proudly declared they didn’t own a television set and TV buffs shook their heads over the expense and inconvenience of going to the movies. Frank Tashlin satirized this division early on (and hilariously) in The Girl Can’t Help It and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?

In reality, the two media were often closer than partisans would admit, with moguls freely shifting talent and resources from one to another. Universal, the studio that invested most seriously in TV production, would reap the benefits many times over.

In a more material sense, the first few decades of television broadcasting would be inconceivable without film. Local stations, especially unaffiliated ones that relied on syndication deals and back catalog feature film packages to fill out their schedules, were grindhouses in all but name, projecting celluloid prints of TV content hour after hour.

The artifacts of this era are still floating around the collector’s market today.

How do you know a TV print when you see one?

How do you know a TV print when you see one?

Odds are, it has more change-over cues than usual. Instead of the usual, discreet circles in the corner every twenty minutes, prints shoved through the TV wringer may possess them every five. There may be multiple sets—the original ones printed over from the duplicate negative, scratch cues scribed by a station manager, star-shaped hole punches in triplicate, whatever else you can imagine.

Whereas change-over cues in theatrical prints serve to guide a smooth and inconspicuous switch from one reel to another, TV cues functioned in exactly the opposite fashion, facilitating interruption, namely commercials, station identification breaks, sponsorship spiels, news updates, and the like. Today former TV prints still carry this additional content or, more commonly, bear traces of it in the form of slugs (a small length of black leader).

Credits, especially main titles, were often re-photographed with the aim of re-branding corporate product, re-naming properties so as not to conflict with newer programs, or simply making the text more legible on a 10-inch screen.

This abuse was standard, as indicated in Movies for TV, an early (1950) guide for station directors:

[T]here may be cases where the station has bought a film or agreed to edit some. This often gives the [station’s] film director a heaven-sent chance to eliminate some shots which detract from its over-all enjoyment due, perhaps, to an overabundance of medium long shots or long shots. For a half-hour airshow, we use twenty-seven minutes of film. [A high proportion. It was later whittled down to twenty-two or twenty-one. – Ed.] This may mean that three minutes or more have to be cut from the film under consideration. Very dark shots can be eliminated; perhaps some which are too contrasty with a large amount of white in them can be dyed and toned down by graying the whites.

The narrative derangement all but guaranteed by this system (the same guide earlier suggests the elimination of close-ups of letters and notes or the outright rejection of films containing such hindrances) throws our sense of screen history into befuddled disbelief. What was and was not seen on TV was dictated by prosaic concerns as often as political ones. Anything goes.

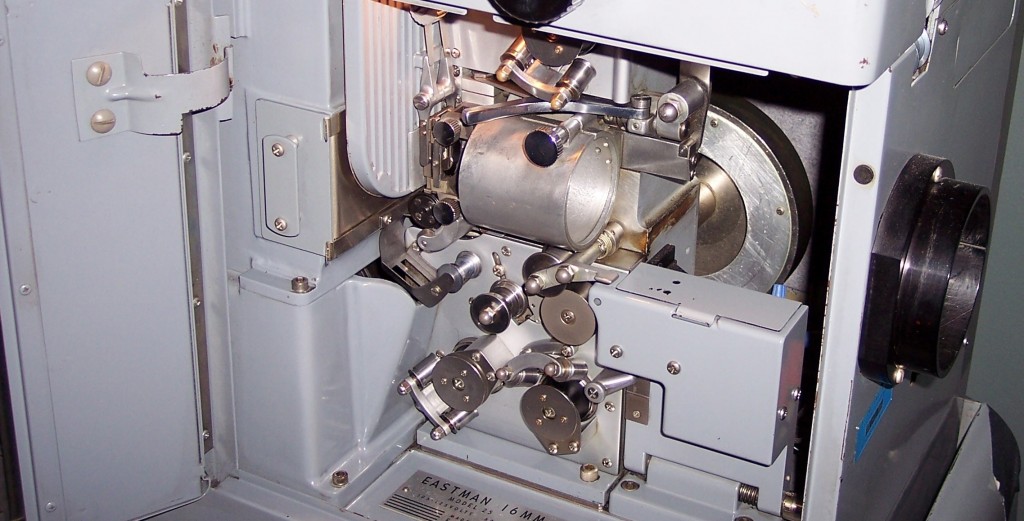

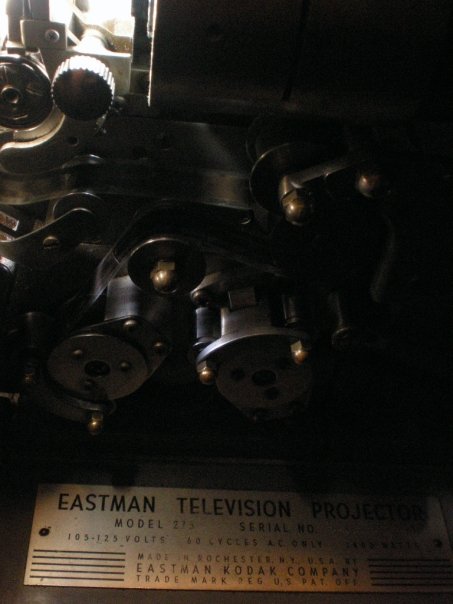

For all the haphazard-seeming practices perpetuated at local stations, the distance of history also provokes genuine admiration of the operation. To take but one example, consider the Eastman Model 25—also commonly known as the Eastman Television Projector. (The basic design and guts of the 25 were later branded as the 275, the 285, etc., but they are all functionally identical.)

For all the haphazard-seeming practices perpetuated at local stations, the distance of history also provokes genuine admiration of the operation. To take but one example, consider the Eastman Model 25—also commonly known as the Eastman Television Projector. (The basic design and guts of the 25 were later branded as the 275, the 285, etc., but they are all functionally identical.)

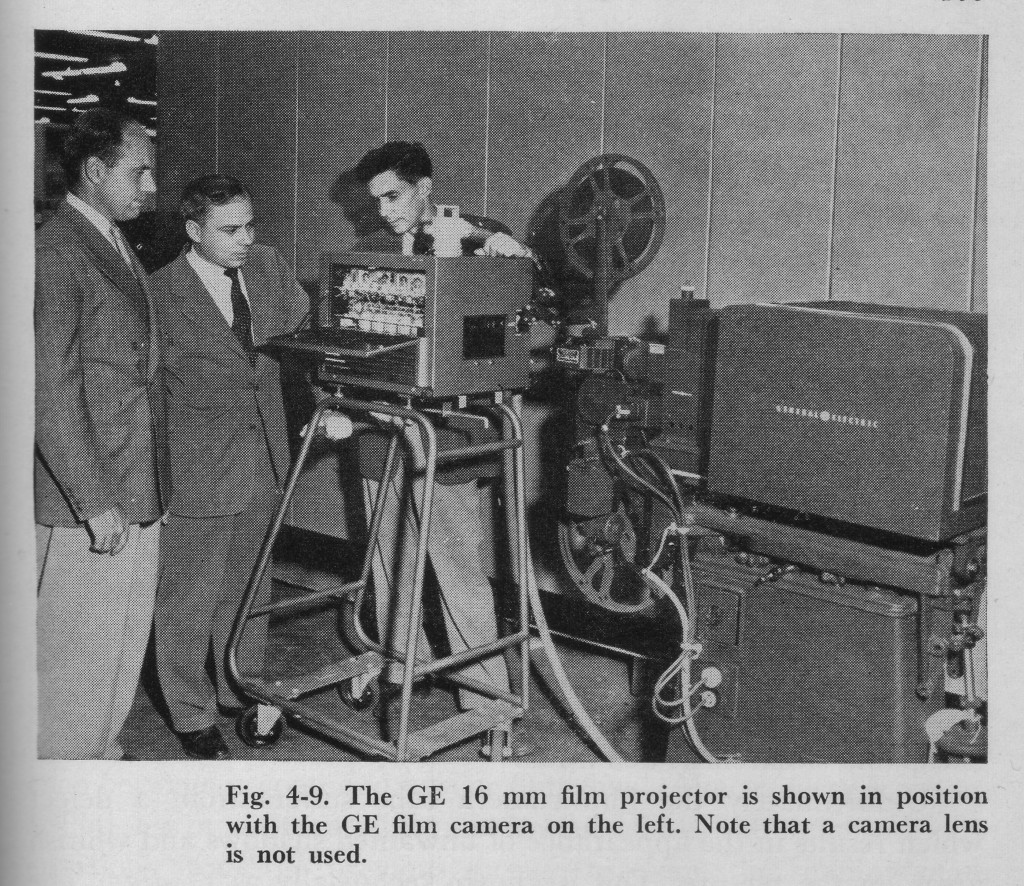

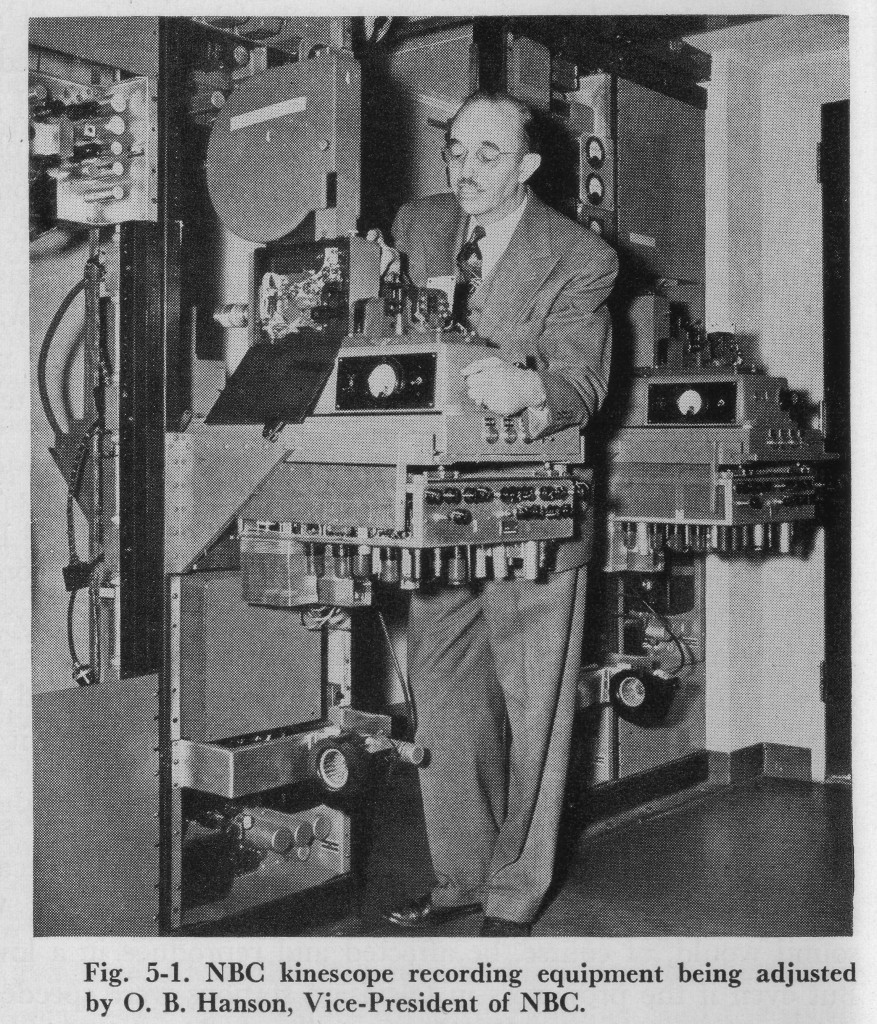

The Eastman 25, introduced in March 1950 for $3,675, constituted the film part of an early film chain—station speak for a film projector aimed at a television camera, transmitting the content direct-to-air. In the video age, the film chain principle was adapted into the telecine, later the datacine and the high-resolution film scanners used for transfer today.

The Eastman 25, introduced in March 1950 for $3,675, constituted the film part of an early film chain—station speak for a film projector aimed at a television camera, transmitting the content direct-to-air. In the video age, the film chain principle was adapted into the telecine, later the datacine and the high-resolution film scanners used for transfer today.

If your experience of 16mm projection is limited to portable machines, the Eastman 25 is a quiet revelation. To be sure, 16mm was predominantly shown on table-top set-ups—in classrooms, churches, union halls, camp sites, army bases, etc. The equipment was made to match—relatively light-weight, replete with plastic rollers, often slot-loaded or almost-fully automated. Bell & Howells, Elmos, Eikis, and their imitators had to be loaded on A/V carts and transported through hospital corridors and factory floors—a roving educational unit.

The Eastman 25 is totally different, and a fitting subject for historical archeology. Every part is metal. Nothing in its threading path is automated or hidden behind a faceplate. It is imposingly permanent, with a footprint as large as many 35mm models. Indeed, it even includes features—such as the lever to lock the focus knob—that would be very useful in, but are often omitted from, 35mm machines. And in a way, this makes sense: though the limitations of transmission equipment and home sets were formidable, each 16mm television projection commanded a larger audience than most any auditorium presentation in either gauge.

In other words, the Eastman 25 is an industrial-strength 16mm projector meant to run film every hour of every day for years and years. Though the Eastman 25 was designed squarely for television use, its robust excellence later made it a very attractive model for repertory houses, cinematheques, laboratories, and other institutions that required a permanent and reliable 16mm installation.

In an age when business increasingly turns to consumer hardware and forgoes the proven durability of wholly mechanical equipment, operating an Eastman 25 still feels like a rare privilege.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be presenting TV on Film tonight at Cinema Borealis. Five hours of vintage television programming, all shown in 16mm and 35mm prints. Come and go as you please. Please see here for more information.