The first period of classic horror films (1931-1935) is rightly dominated, in popular memory and in sheer evergreen salability, by Universal Pictures. Boy wizard producer Carl Laemmle, Jr. was the first to realize the raw potential of a genre previously and unproductively tethered to stage conventions. Innumerable silent horrors look amazing in stills but prove leaden on the screen, encumbered by the belief that every one-part terror has to be balanced by three-parts comedy relief. The sobriety of the early talkie terrors—not only no comedy, but often, too, no music and a halting slowness that presupposes a distinctive kind of viewer engagement—remains notable today. More than any other films of the period, these productions express the moguls’ instinctive anxieties about the Old Country: famine, disease, monsters, indecipherable lumpen accents, peasants always on the verge of some stupid revolt.

The first period of classic horror films (1931-1935) is rightly dominated, in popular memory and in sheer evergreen salability, by Universal Pictures. Boy wizard producer Carl Laemmle, Jr. was the first to realize the raw potential of a genre previously and unproductively tethered to stage conventions. Innumerable silent horrors look amazing in stills but prove leaden on the screen, encumbered by the belief that every one-part terror has to be balanced by three-parts comedy relief. The sobriety of the early talkie terrors—not only no comedy, but often, too, no music and a halting slowness that presupposes a distinctive kind of viewer engagement—remains notable today. More than any other films of the period, these productions express the moguls’ instinctive anxieties about the Old Country: famine, disease, monsters, indecipherable lumpen accents, peasants always on the verge of some stupid revolt.

The other studios tried to turn out rival scare pictures and their approaches certainly typified their production sensibilities. Paramount turned out highly polished—and less immediately affecting—efforts like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Murders in the Zoo. RKO’s The Most Dangerous Game is only intermittently engaged, but desperate and dreamlike at its best. Warners re-titled its Trilby adaptation after the more dynamic Svengali and made him a pitiable grand-standing striver much at home in the Burbank rogue’s gallery; the same studio’s Doctor X is a (very amusing) newspaper picture with bio-terror trimmings. Small-town-oriented Fox didn’t even try and M-G-M probably wished it hadn’t either after Freaks.

Harry Cohn’s Columbia, superficially the studio positioned closest to Universal with respect to capital and assets, finally released a horror picture at the very end of the cycle. Early production notices announced a property called The Black Room Mystery—but mysteries are something read by mostly respectable men and women in mostly respectable circumstances. This was no S.S. Van Dine. Studios pegged horror entries for the subliterate masses, the American equivalent of those torch-bearing villagers across the Atlantic.

The studio embarked on a horror entry as they would any other Columbia picture, namely poaching resources and talent. Village exteriors were shot on Universal’s standing Frankenstein set and Czech émigré extras were encouraged to bring their own costumes. Boris Karloff, then at the end of his first Universal contract and publicly decrying that studio’s treatment, was eager for a change and a Columbia quickie fit the bill. A syndicated article gave the actor an unusually candid platform:

Until a few months ago, Karloff was under exclusive contract to Universal. He could play only such roles as the studio wanted him to play, like mummies and malformed creatures while this company controlled his career….

“I can’t wear a false face all the time … I do not in the least object to being a heavy, but a masked heavy …!

“The vogue for monstrous men in the movies can’t last forever. When it ends, where will I be if I specialize in them? Out in the well-known cold. I am trying to establish myself as a character player—without make-up—and since the termination of my original contract I have been quite successful.”

The Black Room was a perfect Karloff vehicle for 1935. Not only did it prove he could play a role without make-up, it was a double performance with wholly divergent mannerisms and sensibilities—the kindly Anton de Berghmann and his mad brother Gregor. (As a climactic fillip, Karloff blends the two, as one brother must imitate the other.) It was a conceptual performance tucked away dead center in a movie where sophistication was guaranteed to go unnoticed.

On some level, it’s difficult to separate The Black Room from a general bout of unconfidence special to Columbia. When watching Columbia films from the 1930s, one always gets the feeling that the technicians are working overtime on limited resources. They’re paced in a certain hurried way—a fast tempo, but distinct from the Warners one. There, the studio wanted product with a vulgar forward motion; at Columbia, the crew just wanted to get it done. They shared common knowledge that the front office wouldn’t recognize or care about quality. They wouldn’t really know what to do with a good movie if they made one and might be a bit ashamed if they did.

The Black Room happens to be a good movie and not just because of Karloff. It has a unified sense of cinematography, set design, costume, and music that triumphs over, but never calls attention to, its low budget. Despite the generations-spanning curse that sets the plot in motion, it’s a genuinely modest film that knows it’s doing something very well and leaves it at that.

Edward Bernds, the sound man for The Black Room (and coincidentally, the director of the Three Stooges short “Who Done It” that will accompany our screening of The Black Room), sketched a congenial portrait of director Roy William Neill:

Roy Neill was soft-spoken and gentlemanly unlike most of the ‘loud-speaker’ directors at Columbia—Lew Landers, Lambert Hillyer, Ross Lederman, Al Rogell, C.C. Coleman, and the like. And this made him an ideal director for Karloff….Karloff liked and respected Roy Neill. I think Karloff recognized the ‘try-for-quality’ that Neill made….

The production office would get on him, tell him to get the scheduled day’s work or else, and Roy was too gentle and submissive to argue. So he’d try to speed up. But he was genuinely incapable of shooting anything really sloppy—and we’d often work far into the night. We knew him—not in his presence—as ‘rocking chair’ Neill. That was because he had to have a rocking chair on the set … He sat there and rocked, and we worked far into the night—that was Roy Neill.

This image of a craftsman meeting front office demands from the serenity of a rocking chair pretty well encapsulates the appeal of Columbia productions in this era: low-key dignity.

This image of a craftsman meeting front office demands from the serenity of a rocking chair pretty well encapsulates the appeal of Columbia productions in this era: low-key dignity.

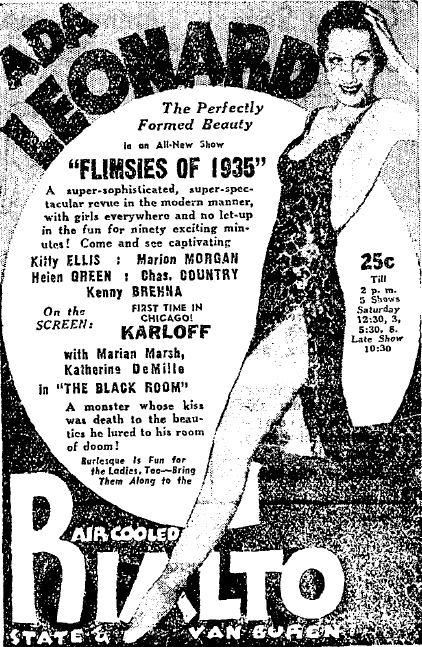

Columbia wasn’t embarrassed to release The Black Room, per se, but their promotional push was tepid. Trade reception was unenthusiastic—perfunctorily impressed with Boris Karloff’s dual performance and the technical feats that brought it seamlessly to screen, but there’s also an obvious exhaustion with the whole terror fad and a level of decent-if-you-like-that-sort-of-thing alienation evident. The big metro papers barely covered it, befitting a quiet release in major markets in August 1935. In Los Angeles, it played on the bottom half of a bill with RKO’S Jalna. In Chicago, it was supporting fare for a live burlesque show at the Rialto (Flimsies of 1935; tagline: “Burlesque Is Fun for the Ladies, Too”). The Brooklyn Fox was the closest Black Room ever came to New York and it never received a notice in the Times.

Notably, this superficially political picture had a decent run in Washington, D.C. and the Post published a review that confirms The Black Room’s middling stature:

No one could be more surprised than we are—this is a good picture!

Which only goes to show that two Karloffs are better than one. In his first dual role, this much make-up-maligned Englishman is allowed to do some acting (a thing he is very good at), and also to be rather attractive in one characterization.

If you’re looking for Frankenstein or some sort of a fantastic monster and all manner of cheap, ridiculous horror, don’t come here. “The Black Room” is an intelligent horror play, rather more interesting than scream-at-able, but with fine regard for sinking feelings and excellent climaxes….

“The Black Room” deserves more than being kidded—it’s extremely good and just about shivery enough for a summer night.

The place to look for unqualified excitement over The Black Room was in the papers of small- and medium-sized towns that were happy to get anything and treated it as a semi-major event through spring of 1936. This is where one reads sincere notices (reprinted from wire services) about Karloff finally getting a good night’s sleep without a four-hour appointment in the make-up chair. (This halted the usual side effect of undesired weight loss. Just another working stiff.) Unsigned promotional copy in the Virgin Islands Daily News gives something of the delirious flavor promised:

SEE KARLOFF IN THE BLACK ROOM SUNDAY

Friend of a room of doom! His kiss the password to oblivion-and dead or alive he can kill! His latest honor roll a ruthless killer, a bluebeard, who entices beautiful girls into the Black Room of his castle, only to take their lives. He himself lives under the dread malediction that he is to meet at the hands of his younger twin. Finally he murders his brothers [sic] in an attempt to defy the curse-but he ultimately meets death at the hands of the corpse. Devil with a private graveyard . . . . . demon with the kiss of death!

How? Why? See!

Since 1935 The Black Room has returned periodically with familiar treatment. It was reissued theatrically in 1955, at which time the original title cards were permanently altered for wide screen projection. Following that run, TV exposure was much more common than theatrical outings. A 2006 DVD from Sony included The Black Room in a nimble and ugly box set with three other Columbia Karloffs; its generic menu, which recalled a CompuServe CD-ROM from 1998, is the latest in a line of minor, unthinking indignities.

Since 1935 The Black Room has returned periodically with familiar treatment. It was reissued theatrically in 1955, at which time the original title cards were permanently altered for wide screen projection. Following that run, TV exposure was much more common than theatrical outings. A 2006 DVD from Sony included The Black Room in a nimble and ugly box set with three other Columbia Karloffs; its generic menu, which recalled a CompuServe CD-ROM from 1998, is the latest in a line of minor, unthinking indignities.

Needless to say, seeing a restored 35mm print from Sony Pictures Repertory on the big screen will go a long way towards setting things right.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening The Black Room in a 35mm print from Sony Pictures Repertory at the Portage Theater on October 5 as part of its Classic Film Series. Special thanks to Christopher Lane. Please see our current calendar for more information.