Can we talk about a fundamental division in film-going?

Most of us look at movies and see stories and actors—shifting pleasures for which the highest praise is timelessness. A performance that endures, dialogue that remains quotable, storytelling that ‘holds up’ on repeat viewing, whether in a theater or on television or streaming over Netflix. (The virtues can be consumed and appreciated in any medium.) It’s common to overhear laments that a film ‘doesn’t stand the test of time’—implying that a film can be a great emotional experience in one moment and merely an antique in another, creaky and tinny precisely because it gives dramatic form to an outmoded concern or a topical obsession. Such does not a classic make.

But there’s another kind of film-going, rooted in things rather than professionally timeless. The good folks at the Vitaphone Project are interested in early talkies for their specificity (in time and in technology), but in an expansive way. Emphasizing the recording and playback method, not necessarily the thing being heard, sounds odd at first—a cart without a horse.

But the cart matters a lot. The Vitaphone system briefly united the phonograph and the film projector, producing audible entertainment where the brand itself was often the primary subject. With the Vitaphone, you could hear the Metropolitan Opera or the lowest dregs of a vanishing vaudeville. Indeed, Vitaphone is fascinating partly for the way it bridged and made a record of worlds whose dissolution it assured. On some level, of course, you must be interested in the music and popular culture of New York in those years (1926-1930)—any and all of it—to appreciate what the Vitaphone wrought.

But the cart matters a lot. The Vitaphone system briefly united the phonograph and the film projector, producing audible entertainment where the brand itself was often the primary subject. With the Vitaphone, you could hear the Metropolitan Opera or the lowest dregs of a vanishing vaudeville. Indeed, Vitaphone is fascinating partly for the way it bridged and made a record of worlds whose dissolution it assured. On some level, of course, you must be interested in the music and popular culture of New York in those years (1926-1930)—any and all of it—to appreciate what the Vitaphone wrought.

As a sound reproduction system, it was sonically superior to Fox’s Movietone process—at first. As optical soundtrack technology improved, the Vitaphone’s flaws could not be ignored. For projectionists, this was a very cumbersome technology. Running a feature meant at least three people in the booth—two to run the projectors and another to synchronize the 16-inch disk to the picture. Anything but constant and even playback of sound and image broke synchronization between the two. (The popular conception of early talkers from Singin’ the Rain is not far wrong.) Damaged frames could not simply be spliced out; they had to be replaced with equivalent black leader to maintain sync. The discs themselves wore out after a handful of plays, with replacement necessary for long runs.

(Or maybe this isn’t so strange. At century’s end, DTS playback from a special CD-ROM drive easily bested the lossy and unreliable digital sound offered by Dolby. And today’s IMAX screens sync a mute 70mm print to an audio file on a computer without the benefit of DTS’s timecode.)

To be attracted to the Vitaphone, you need to be a film buff, record collector, and historian of half-forgotten popular arcana all rolled into one. Ron Hutchinson of The Vitaphone Project is all these things and more. We recently conducted an interview with Ron over email about Wednesday’s feature and the Vitaphone Project more generally.

KW: SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD is a film that isn’t generally known as a top-line classic, but may as well be in Vitaphone circles. Can you explain its appeal?

KW: SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD is a film that isn’t generally known as a top-line classic, but may as well be in Vitaphone circles. Can you explain its appeal?

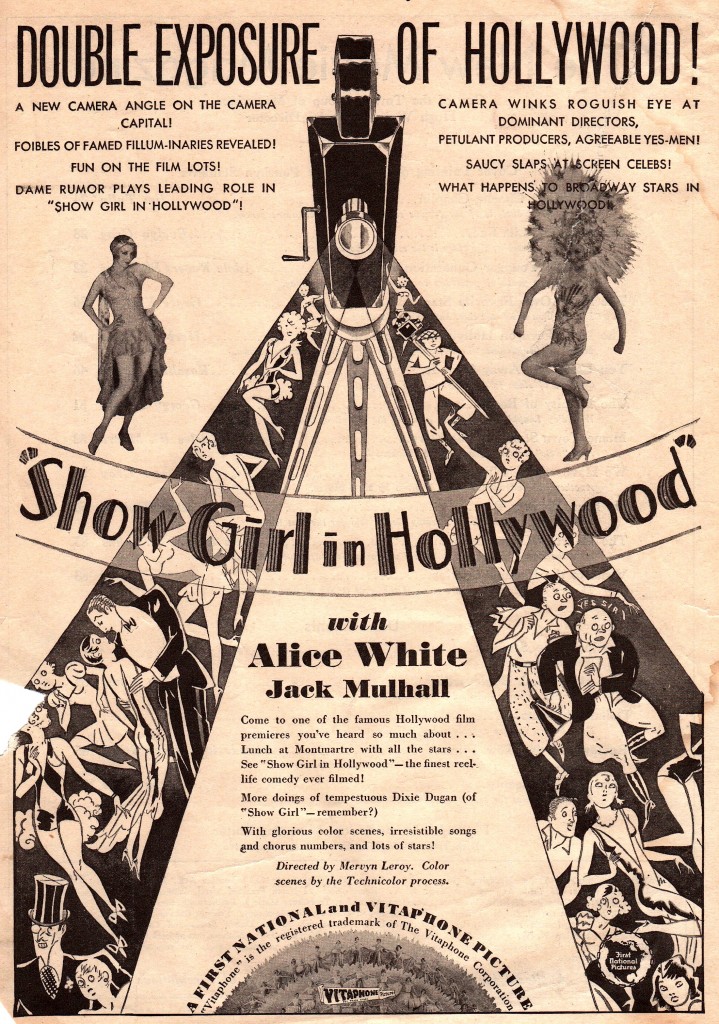

RH: This is a film that really has it all for early talkie fans. It features perky Alice White, then girlfriend of the film’s director Mervyn LeRoy, in a part perfectly suited to her perky personality. The film is loaded with scenes of the First National studio lot. It moves quite well for an early sound film, and features two big production numbers that were originally filmed in Technicolor. Silent star Blanche Sweet turns in an outstanding and naturalistic performance as the star who is over the hill at 32. And of course we see the Vitaphone recording process prominently during the “I’ve Got My Eye On You “ number.

KW: One of the things that makes SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD such an interesting film is, of course, the scenes of a film being shot with the Vitaphone process. If the same script had been filmed a year later, the details would be very different. What can this film show and teach us that we wouldn’t otherwise know?

RH: This is one of the few theatrical films that show the Vitaphone disks being cut while filming. And we see the three cameras grinding away simultaneously from inside their large box-like soundproof kiosks. The film was released in April, 1930, and ironically Warner Brothers had already started their switch from disks to sound-on-film like all the other studios. Initially, the Vitaphone disk system provided sound quality superior to the sound-on-film Movietone process. But by 1930 film soundtracks were as good as Vitaphone. So it was hard to justify the many negatives the disk system presented, including the cost of pressing and shipping the disks, breakage, potential synchronization problems, difficulty in editing and of course limited ability to film outdoors. SHOWGIRL IN HOLLYWOOD gives us a wonderful glimpse of what filming in the Vitaphone process was really like.

KW: More than most archivists and historians, the members of the Vitaphone Project seem to be engaged in active detective work. Can you describe the background work that usually goes into a restoration of a feature like SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD?

KW: More than most archivists and historians, the members of the Vitaphone Project seem to be engaged in active detective work. Can you describe the background work that usually goes into a restoration of a feature like SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD?

RH: The Vitaphone Project began in 1991 by a handful of record collectors who also loved old films. Vitaphone combined both areas. Our goal is to seek out the 16 inch soundtrack disks that may be in private hands and match otherwise mute surviving 35mm picture elements. To date we have located over 3500 disks and been involved in the restoration of over 140 1926-30 Vitaphone shorts and features. Many are now available on DVD from Warner Archive.

The restoration work is done by the gifted team at UCLA’s Film and Television Archive. The process involves cleaning up both sound and picture separately. An optical track is created of the disk on 35mm film and painstakingly re-synchronized to the picture to create a new, projectable 35mm sound-on-film print. Funding has come from many private individuals as well as Warner Brothers. Film elements usually are borrowed from The Library of Congress.

KW: One of the most fascinating aspects of the Vitaphone Project, for me at least, is the fact that sound-on-disc stays around as an exhibition medium fairly long after it’s abandoned as a production method. You regularly find discs for films that we usually think of as sound-on-film features. What can learn by collecting and listening to oddities like this?

RH: The reason disks for post-1930 features are found is because in the early thirties, there were still over 3000 theatres that could only show talkies in the disk format. That was the cheapest way to convert from silent to sound when the revolution began. The studios accommodated those theatres as late as 1935 by pressing disks from the optical sound-on–film soundtracks. Even Warners stopped recording directly on disk around March 1930. So all disks pressed after then, by studios like MGM and RKO, were in fact transfers from optical tracks.

KW: Can you describe any exciting discoveries that the Vitaphone Project has made recently? New restorations underway?

RH: The discoveries of soundtracks never seems to slow down. We average several hundred new soundtrack discoveries a year. People with disks as well as relatives who worked in the films easily find us on the internet. I personally learned about and acquired a collection of over 70 Vitaphone disks this spring. Out of those, over a dozen film can now be restored with their previously lost soundtracks. We continuously work with UCLA, Warner Brothers, The Library of Congress and private collectors to keep the restoration pipeline full. Warners recently completed restoration of 53 shorts, all on the new Warner Archive VITAPHONE VARIETIES DVD set. As of this writing, there are potentially 60 more Vitaphone shorts in the pipeline. Every discovery is exciting, of course. But among the more interesting recent ones are disks for MOLLY PICON, THE CELEBRATED COMEDIENNE (1929), DAVE APOLLON AND HIS RUSSIAN STARS (1929), and a number of 1929-30 Columbia shorts filmed by Victor Talking Machine Company in Camden, NJ. These are being restored by The Library of Congress using disks I located in Australia. I expect they will be screened within the next year. Most exciting among this batch are MAMIE SMITH in ‘JAILHOUSE BLUES’ starring the legendary blues singer, JULES BLEDSOE in ‘OLD MAN TROUBLE’ with the original cast member of “Showboat” and NAN BLAKSTONE in ‘SNAPPY COEDS’, an incredibly peppy and risqué short by the comedienne later known for her ‘party’ records.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Show Girl in Hollywood in a restored 35mm print from the Library of Congress at the Portage Theater on August 10. Please see our current calendar for more information. Special thanks to Rob Stone, Lynanne Schweighofer, and especially Ron Hutchinson. Please visit the Vitaphone Project and consider a donation. All images courtesy Ron Hutchinson.