I first became interested in the film version of Native Son when I was reading over a list of films that the Library of Congress had preserved in 2004. Amidst countless Vitaphone shorts, the original Superman serial, and silent features from forgotten and one-off production companies like Davis Distributing Division, Paralta Plays, Inc., Arrow Film Corp., and Ivan Films, Inc., there was also Native Son, seemingly removed from the others by time and space. As I read up on the film, it just became more interesting—an independent production that starred the author of the landmark novel, shot not in America but Argentina. Even Oscar Micheaux, ever-marginal, never had to make a film in exile.

Contemporary accounts of the film throw the nature of that exile into relief. The book had already been adapted for the stage in 1941 by no less than Orson Welles; actor Canada Lee was cast as Bigger Thomas and the play went on to a long run. It proved popular enough to entice Hollywood. Even MGM, the studio with the sensibility farthest afield from Wright’s, expressed interest. Wright eventually turned down a $50,000 offer for the screen rights, fearing that the film would desecrate the book. (He was undoubtedly right: talk centered on a white-cast version with assorted cuts to appease Southern exhibitors.)

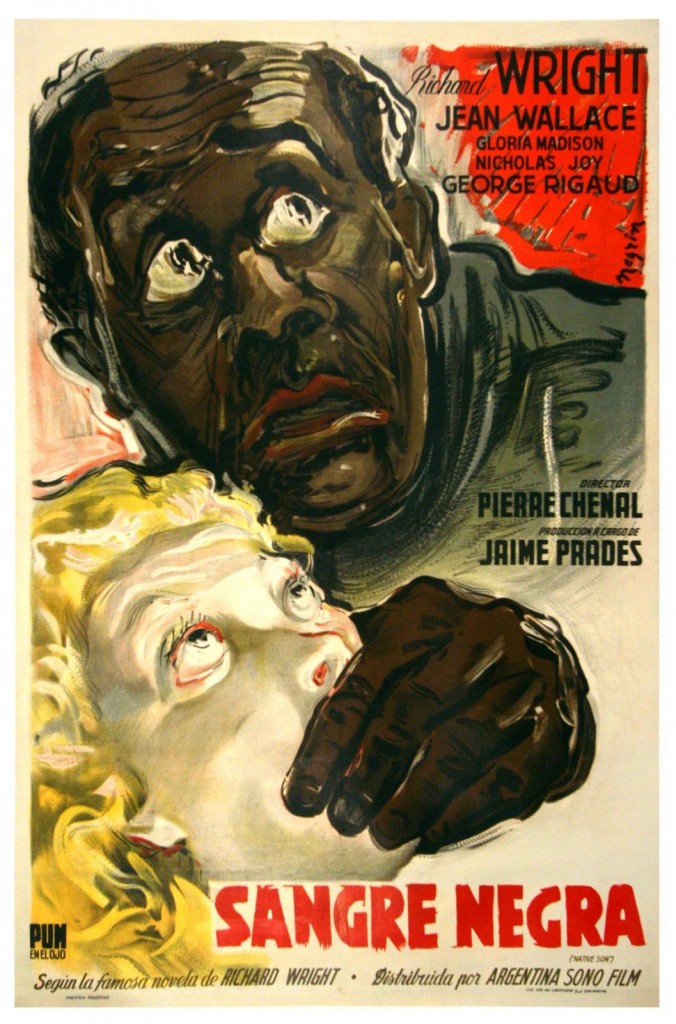

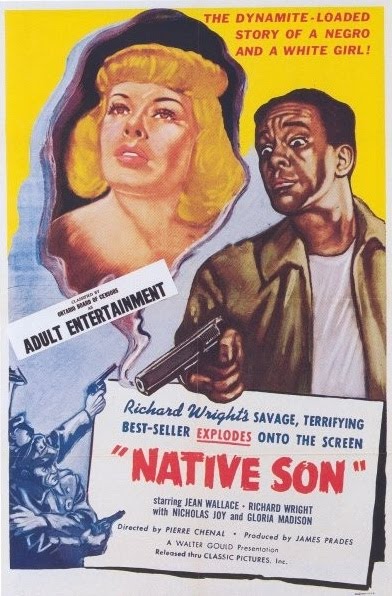

Renewed talks for a screen version began at a Parisian café, where director Pierre Chenal, producer Jaime Prades, and Argentina Sono Films head Artillo Mentasti convinced Wright that an unexpurgated rendition could be filmed in Argentina, which had also seen long runs of the stage production (in Spanish, with a white cast). Believing that Argentina was anything but a US client state, and thus indifferent to the potential consequences of an incendiary picture of American race relations, Wright set up shop at Sono Film.

It was exile, but it did not come cheap. The New York Times reported on the production from Buenos Aires, citing its budget as five million pesos, five times the average cost of an Argentine feature. The Chicago Defender proudly exclaimed it ‘the biggest and the best movie ever produced in South America.’ The Times described one particularly ironic expenditure:

An Argentine film company, located in the fashionable suburb of Martínez, recently constructed its most ambitious set—an entire block of slums, supposed to be in Chicago. Now all companies here are a bit hard pressed: they watch centavos with more concentration than Hollywood centers on dollars, and there are real slum areas, although fewer than in most great cities, right here in Buenos Aires. There is actually a slaughter district known as Nueva Chicago, but even that would not do. This had to be a very special slum; it had to be right out of Chicago because it was to serve as the setting for Richard Wright’s “Native Son” …

There were, of course, authentic bits of Chicago in the picture. Background inserts were shot here. Wright found conditions on the South Side worse than they had been a decade earlier. “We looked for abandoned tenements,” Wright told the Times, “but there weren’t any. They are all full of people. And the tension has grown.” More authenticity: the only other American actor in the cast was Gloria Madison, a University of Chicago student with no acting experience who won the part of Bessie at an open audition.

The film was apparently finished in 1950 for a Venice Film Festival premiere, but its exhibition in 1951 proved rocky. Characteristically, Variety lamented its anti-American sentiment but predicted box office success in Latin America on precisely that basis. Details of Native Son’s performance abroad are scant, but the film received great resistance in the US, with the New York State Censors demanding extensive cuts. It was rejected outright in Ohio for “present[ing] racial frictions at a time when all groups should be united against everything that is subversive.” When the Chicago Defender finally got a chance to see the film in New York, the pre-release puffery of its earlier dispatch was quickly refuted:

The film was apparently finished in 1950 for a Venice Film Festival premiere, but its exhibition in 1951 proved rocky. Characteristically, Variety lamented its anti-American sentiment but predicted box office success in Latin America on precisely that basis. Details of Native Son’s performance abroad are scant, but the film received great resistance in the US, with the New York State Censors demanding extensive cuts. It was rejected outright in Ohio for “present[ing] racial frictions at a time when all groups should be united against everything that is subversive.” When the Chicago Defender finally got a chance to see the film in New York, the pre-release puffery of its earlier dispatch was quickly refuted:

“Native Son” on film has its “Bigger Thomas,” the hero but here the likeness ends. This despite the fact that Richard Wright who wrote the book is cast in that important role. In fact you dislike the pix as much because of the presence of Wright as anything else. Wright the author and Wright the actor suffer quite a bit in comparison—one with the other.

However the trouble with Pierre Chenal and Richard Wright’s movie version of “Native Son” does not begin with portrayal of “Bigger” Thomas nor does it end there….

Those things brought out in the book as responsible for “Bigger” are conspiciously [sic] absent from the film leaving the audience with no choice but to condemn the accident charged to him twice in the play.

The Defender review ended with the sad and extraordinary verdict that Native Son on screen was no better or worse than The Birth of a Nation.

Native Son was distributed in the US by Classic Pictures, which had its offices at 1560 Broadway in New York. Not much is known about this outfit or the personnel affiliated with it. Their major release, an English-language version of Curt Oertel’s The Titan—Story of Michelangelo, won an Academy Award for Best Feature Documentary and enjoyed extensive non-theatrical circulation. The chain of ownership for Native Son is obscure enough to make it an orphan film today—that is, one that probably is, or may as well as be, in the public domain.

Suffice it to say, the film has not been much re-evaluated. (Most every account begins and ends with an incredulous observation that Wright is too old to play “Bigger” and the film thereby suffers.) Part of this undoubtedly stems from the paucity of quality copies. If the film has been seen much since 1951, it’s largely been from mediocre VHS tapes.

The Library of Congress restoration rights this wrong and allows us to look at the film with fresh eyes. Even if Native Son possesses all the problems aired at the time of its original release, it is still a movie with credentials we are best not to ignore; can you name another film where an American author literally enacts his major novel?

The Library has two versions of the film—an uncut international version and another with the cuts mandated by the New York State Censors. Both have been preserved. I interviewed James Cozart, who oversees Motion Picture Quality Assurance for the Library, about the restoration via e-mail:

KW: Native Son is a film with a very complicated national identity–based on a classic American novel but shot in Argentina by a French director. How did something like this wind up at the Library of Congress? As well, how was it decided that a film with such an international pedigree as Native Son should be the Library’s responsibility to preserve?

JC: It is a long story and parts of the pre-history simply are not known.

The Library previously had a safety base print of this title that we received in 1951 from copyright deposit. We were in no hurry to make a preservation until we discovered that there was early safety deterioration on the mixed safety and nitrate preprint source material in this film. This additional better source was acquired in 1993.

The copyright deposit print was very worn and it was not used in our restoration, although we used it as a guide to match the look of our restoration.

The superior source of mixed nitrate and safety used in our restoration came from Archivo General de Puerto Rico.

Apparently these multiple version preprint copies were found in an abandoned nitrate vault in Puerto Rico.

How they got in Puerto Rico is anyone’s guess, but the Puerto Rican archives also found material on Kubrick’s Fear and Desire in there, too. On that title, one guess might be that Joseph Burstyn hid his most valuable assets when he declared bankruptcy and a few years later took the secret of where they were hidden to the grave with him. It is not known by me if Burstyn had any connection with Native Son, just that the films were found in the same location. In fact, some of the Native Son reels were actually found misidentified as the Kubrick film.

Why would we preserve this title? Simply because it is US History, even though more of it was shot in Argentina than in Chicago.

Bruce Horrell coordinated most of the restoration on this title and I did the rest.

KW: Native Son dates from 1951, which puts it roughly at the end of the nitrate era. The Library tends to focus its preservation efforts on nitrate material and, if I’m not mistaken, has not preserved or restored many films that date past 1951. Can you explain this policy and how it fits with the broader priorities of the Library?

JC: As a rule of the thumb, where we have nitrate and safety mixed, and the storage has been in a damp location prior to the Library acquiring it, the safety is the first to go. That was the case here, with about 40 years storage in an abandoned vault.

If safety and nitrate are kept separate and dry, the safety usually will outlast nitrate, so we usually give a higher priority to sources that exist only on nitrate. We judge this on a case-by-case basis and there are many exceptions.

KW: Did Native Son pose  any particular preservation challenges? What did you start with and how many passes did you have to make before arriving at the final preservation print?

any particular preservation challenges? What did you start with and how many passes did you have to make before arriving at the final preservation print?

JC: This restoration was unique in that the only reprint that I can remember was in the New York State Censor version. I cannot remember any in the complete international version that you will be showing. In fact, the actual preservation took far less man hours than did the very careful preprint inspection to determine which source was to be used at which point in the film. In fact the safety deterioration in some of the sources was so bad, that we discarded much of the vinegar syndrome safety material after it was preserved.

KW: This print would have been made at your lab in Dayton, Ohio, which has since been moved to Culpeper, Virginia along with the rest of what is now the Packard Campus. How has the new facility expanded the Library’s preservation efforts?

JC: As you mentioned, it is a new facility. We had about 30 years of production in the original Dayton facility, and have had a few early growing pains in Culpeper, but those seem to be worked out now. With more space, we are slowly upgrading both our equipment and personnel, and the future looks a better, if we can get continued funding.

KW: Can you talk about any exciting projects that you’re working on right now?

JC: I’d rather not, as many of these projects are many months and years away. To do otherwise would put undue pressure on the Lab to take shortcuts in slow and difficult process of preservation.

However, I will say that since the longest known copy of Native Son was preserved, an additional foreign version has been discovered and the Library intends to do additional restoration work on this title, at some future date. This will give us three different versions of this title.

James Cozart, Motion Picture Quality Assurance Library of Congress, Packard Campus, Audio Visual Conservation, 19053 Mount Pony Road Culpeper, VA 22701-7551 The opinions stated are mine alone and do not represent the Library of Congress.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Native Son in a restored 35mm print from the Library of Congress at the Portage Theater on July 6. Please see our current calendar for more information. Special thanks to James Cozart, Mike Mashon, Rob Stone, and Lynanne Schweighofer.